An Analysis of the Roles of Women in Classical Hindu Texts

advertisement

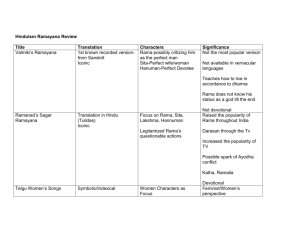

An Analysis of the Roles of Women in Classical Hindu Texts Chris Cherry HUMA 304 10/02/02 Religious texts, regardless of the faiths from which they spring, give the faithful advice on how to live, show a glimpse at history, and set the social norms and rules by which the religion’s adherents are supposed to live. One piece of literature, “The Laws of Manu”, sets strict guidelines on the place in society for both men and women. An epic called “The Ramayana” details the life of Rama and his wife Sita, ultimate examples of right behavior according to the social norms. Both “The Laws of Manu” and Valmiki’s “Ramayana” portray the roles of women in the Classical Period of Hinduism (ca. 500 B.C.E.-500) from different perspectives, but in the end set fort the same rules and ideals, including the dominance of men over subservient women. In the Ramayana, Sita, the wife of Rama, is portrayed as an ideal Hindu woman, beautiful, chaste, and fully aware of her duties. During the wedding, her beauty is extolled in phrases like “the sweet-eyed Sita”, with the “bridal blush upon her brow” (Valmiki, 64). Her father Janak gives his “beauteous daughter” to Rama in marriage, pronouncing in the wedding vows that she is “the best of women” (Valmiki, 64). Sita’s beauty in the Ramayana is surpassed and eclipsed by her complete submission to her duty as wife. In her wedding vows, Sita is given to Rama by her father, with the father telling Rama that she is to be “henceforth sharer of thy virtue,” “faithful wife,” and “of thy weal and woe partaker” (Valmiki, 64). She is thus bound to her husband, and released from her father’s care into Rama’s. Her sense of duty is again shown upon Rama’s banishment into the wilderness. Although Sita is not required to go into exile with Rama, she wishes to do so. She feels that “the faithful woman follows where her wedded lord may lead,” and that “with her lord she falls or rises” (Valmiki, 64). She decides to follow him into hardship, wandering the jungle, where she will be “happier than in father’s mansions” living “with a faithful woman’s pride” (Valmiki, 64). These passages all show how Sita is the ultimate example of a dutiful woman, bound to her husband, in the Hindu tradition. Sita’s chastity comes into question in the third, fourth, and fifth books of the Ramayana. After she is kidnapped by Ramana, a demon, she is held captive until Rama and his friends rescue her. Because she was absent from him, he questions her virtue and devotion to him. To resolve this issue, Sita takes part in a ritual test involving fire to prove her purity and faithfulness. Even so, the people spread rumors about her lack of chastity, and Rama banishes her again to the wilderness to appease the populace. She takes all of this in stride and raises her two sons, unknown to Rama, in the wilderness (Kessler, 63). Through that test of fire Sita exemplifies chastity and virtue, and again accepts her husband’s command as law through her sense of duty. Sita is seen by some in the Hindu tradition as an idea woman, but the Laws of Manu give a seemingly opposed picture of women in Hindu society. They are viewed as property to be managed and guarded, and as corrupted and bad by design. Hindu women are seen as such corrupt beasts that the Laws of Manu call the guarding of women the supreme duty above all others (Doniger, 61). In the Laws of Manu, women are represented primarily as the property of men, pieces of property that cannot own property of their own. The idea of woman as property is clearly spelled out in a listing of potential spoils of war: “…grain, livestock, women, all sorts of things and non-precious metals belong to the man who wins them” (Doniger, 61). Even in the Ramayana, Sita, the bride of Rama, is given to Rama by her father – from one owner to the next (Valmiki, 64). The Laws of Manu also state that women themselves can own only very limited property, as “the wife, the son, and the slave are three (categories of persons) considered to be without property” (Patton, 72). Only wedding gifts, gifts from her husband, and inheritance from brother, father, or mother can possibly be a woman’s property according to the Laws of Manu (Patton, 73). While Sita was viewed as chaste and virtuous and aware of her duty, the Laws of Manu paint a different picture of the rank-and-file woman and her many flaws. Women are seen as things that need to be guarded by men, who should take this task as their supreme duty above all else. As women have a tendency to be unfaithful, according to the text, it is important for men to control and guard them. Since the man “enters the wife, becomes an embryo, and is born again in her,” he must keep her malicious and adulterous nature in check (Patton, 61). Only by guarding a woman, and keeping her free from pollution, can the man guard his children, his descendants, and his own public honor. The Laws of Manu further describe the flaws of women and the ease with which they can be corrupted. According to the text, women are inherently whores who chase after men, regardless of the man’s age or beauty. Their minds are fickle, and they are possessed of a natural lack of affection towards their husbands (Patton, 61). Worldly things like associating with a bad crowd, or being apart from their husbands may also easily corrupt them. Drinking, wandering about, and even sleeping are considered by the authors of the Laws of Manu to be corrupting influences on women (Patton, 61). Men are not only commissioned to guard their wives, but are also required to keep their wives out of trouble by keeping them busy. A woman who is spending and collecting her husband’s money is one who is too busy to get in trouble. By cooking food and looking after the furniture, a woman does her duty to her husband in the domestic realm. Religious rituals of purification also occupy a woman’s time and keep her from bringing shame and sorrow on her family and husband. On the surface, the place of women in Hindu society of the time is reflected in different ways in the Laws of Manu and the Ramayana, but the works are really saying the same things about the role and place of women. While Sita is portrayed in the Ramayana as a perfect wife, mother, and woman, she is still a possession of the men in her life, and bound to their whims. Where women are esteemed on the same level as livestock and grain in the Laws of Manu, Sita is held in similar regard when her father gives her away to her new husband as a possession. Sita is subjected to a test by fire when she claims her innocence to charges of adultery, and even when she passes the test, the people still doubt her, and have Rama banish her. In the Laws of Manu, all women are viewed in this way, as untrustworthy whores who must be watched at all times. It is automatically assumed that women are corrupt in this way. In the Ramayana, Sita is seen as something unusual and different from the ordinary woman precisely because she behaves in a manner that is away from the standard of the Laws of Manu. From her pedestal of perfection, Sita illustrates the ideal subservient, beautiful, and dutiful woman. She is the mythical, unattainable standard to which the fickle, unfaithful women of the Laws of Manu are held. Works of literature give readers a window into the situation and times in which they were written. The texts of “The Laws of Manu” and “Ramayana” show the prevailing opinions of the time on the place of women in society, one through description of the character of women, the other through the story of a woman who behaves admirably. Although these two works are written from different perspectives, they both present the same rules and ideals for women’s behavior, their submission to men, and their sense of duty. Works Cited Doniger, Wendy and Smith, Brian K., trans. “Laws of Manu.” Eastern Ways of Being Religious. Ed. Gary E. Kessler. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company, 2000. Kessler, Gary E., ed. Eastern Ways of Being Religious. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company, 2000. Patton, Laurie L. ed. Jewels of Authority: Women and Textual Tradition in Hindu India. Oxford University Press, 2002. Valmiki. “Ramayana.” Eastern Ways of Being Religious. Ed. Gary E. Kessler. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company, 2000.