The Ontological argument for the existence of God is a rationalist

Analyse and evaluate the Ontological argument for the existence of God

The Ontological argument for the existence of God is a rationalist argument, unlike the empiricist Cosmological and Teleological arguments. While the

Cosmological and Teleological arguments make a case for the existence of

God in addition to the universe, the Ontological argument only concerns itself with the existence of God.

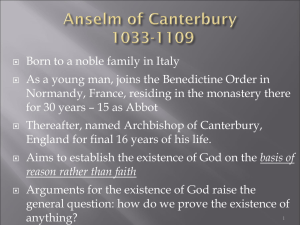

The argument was put forward in its earliest form by St. Anselm.

Anselm, who was a Christian, formulated this argument in an attempt to understand what the Psalms had meant when they said that only a fool knows in his heart that God does not exist; what is it that makes a fool of a person if they deny the existence of God?

He proposed an argument between a theist and an atheist. Anselm described God as the most perfect being possible – if our concept of God can be improved upon, then our concept is not that of God. Therefore, as the atheist’s conception of God as a being that does not exist can be improved upon by simply saying “God is a being that does exist,” the atheist is wrong in his definition of God, as his concept can always be improved upon. As the concept of God as a being that does not exist is a foolish one by virtue of the definition of the word “God,” Anselm argued that God must exist.

Anselm’s version of the argument can be summarised thus:

P1: God is a being than which none greater can be conceived

P2: It is greater to exist in the mind and reality than to exist solely in the mind

C: God exists in reality as well as in the mind

At first glance, this argument would seem very hard to attack; the premises say so little about God that they are very hard to disagree with, and they rely only on what can be known, not what must be experienced, to make their point. However, I hope to show the flaws in the Ontological argument for the existence of God by first questioning the premises of the argument, then questioning the argument’s overall validity.

The first and most obvious point of contention with the first premise is that it begs the question. Only someone who would believe the premise would believe the conclusion. This can be partly rectified by changing the wording of the premise to “God is that than which none greater can be conceived, ” giving a definition of what it means to be God, rather than stating that God is a being which exhibits the qualities of greatness.

Although this revision of the first premise now appears to make it more robust, it is not as analytic as it may seem. Even within those who believe in God, there abound different opinions of what “greatness” entails.

Some, for example, believe Him to be all-forgiving, while others believe He is vengeful. As these two definitions of greatness, in addition to a great many more, are in opposition with each other, we can then surmise that the first premise is synthetic.

We can now move on to the second premise, that it is greater to exist in reality than to exist only in the mind. The main points of contention with this premise are as follows: can “greatness” or “perfection” be defined by a list of attributes and, if so, can existence be listed as one of these attributes? As

Kant states, “’ Being ’ is obviously not a real predicate; that is, it is not a

concept of something which could b e added to the concept of a thing.” He goes on to argue that something which exists in the mind is made no greater by the acquisition of a corresponding thing in reality: “the object, as it actually exists, is not analytically contained within my concept, but is added to my concept synthetically.” We can therefore argue that existence in reality as well as in the mind does not show that something is greater than something which exists in the mind only, as existence in the mind is unable to be compared to existing in reality.

Anselm’s version of the argument has this flaw in common with Descartes’ version, which states that God exists because it is the nature of God to exist.

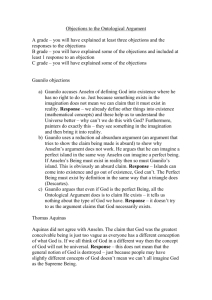

Finally, we must challenge the validity of the argument. There are a number of ways to do this. The simplest method is to create a parody of the argument, as demonstrated in Gaunilo’s Island. In response to Anselm’s argument for the existence of God, Gaunilo proposed a perfect island.

Following the structure of the Ontological argument for the existence of God,

Gaunilo suggested, the perfect island must also exist, in reality as well as the mind. This analogy is, of course, absurd, and neatly points out not only that the conclusion is invalid, but also serves to point out the problems inherent in the premises. The counter-argument for this line of questioning is that, while the most perfect island is the most perfect conceivable example of a specific type of thing, God is the most perfect thing imaginable. Also, that, given the definition of an island, each island is perfectly an island – an area of land surrounded by water.

Another of the problems with the argument, possibly the largest problem, is that there is too large a leap from the premises to the conclusion.

As the premises are of an epistemological nature, we can say that it is impossible to draw the conclusion “God exists” from them; a metaphysical conclusion cannot be drawn from epistemological grounds.

Thus we see that such an apparently unassailable argument is, in fact, riddled with flaws. Better than its empiricist cousins it may be, but, as

Kant concludes his criticism of the Ontological argument for the existence of

God, “we can no more extend our stock of insight by mere ideas, than a merchant can better his position by adding a few noughts to his cash account.”

Sources:

Emmanuel Kant, A Critique of Pure Reason , chapter III

Brian Davies, An Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion

Gaunilo, In Behalf of the Fool, and Anselm’s Reply