Introducing William Blake

advertisement

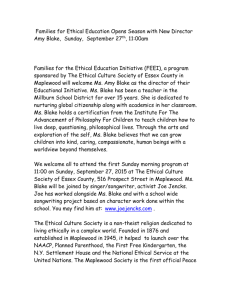

Chapter I. – William Blake 4 Introducing William Blake William Blake (1757-1827), who lived in the latter half of the eighteenth century and the early part of the nineteenth, was a profoundly stirring poet who was, in large part, responsible for bringing about the Romantic movement in poetry. He was able to achieve "remarkable results with the simplest means"; and was one of several poets of the time who restored "rich musicality to the language".1 His research and introspection into the human mind and soul has resulted in his being called the "Columbus of the psyche," and because no language existed at the time to describe what he discovered on his voyages, he created his own mythology to describe what he found there.2 He was an accomplished poet, painter, and engraver. Despite the work of such 17th century baroque poets as Henry Vaughan (1622-1695), and Richard Crashaw (1612-1649), England had no visionary tradition in its literature before the brilliant English poet, painter, engraver and visionary mystic - William Blake. His handillustrated series of lyrical and epic poems, beginning with Songs of Innocence (1789) and Songs of Experience (1794), form one of the most strikingly original and independent bodies of work in the Western cultural tradition. Blake is now regarded as one of the earliest and greatest figures of Romanticism. Yet he was ignored by the public of his day and was called mad because he was single-minded and unworldly; he lived on the edge of poverty and died in neglect. "I know I am inspired!" could be the foundation of his obscurity as well as of his dynamic enthusiasm. He was ambitious for fame; he longed for, even demanded, an audience as enthusiastic as himself, to build the Jerusalem he was looking for in England's green and 1 Appelbaum, Stanley - Introduction to English Romantic Poetry: An Anthology. [Mineola, Dover, 1996.] (Chpt. V.) 2 Damon, S. Foster. - A Blake Dictionary: The Ideas and Symbols of William Blake. [New York, Dutton, 1971.] (Chpt. IX.) Chapter I. – William Blake 5 pleasant land. He was after all writing at a time when the Age of reason was turning into an Age of Enthusiasm.3 But he had a naive, almost arrogant confidence in the power of his own inspiration. Burning with its fire, convinced that to hear him must be to applaud, he failed to realize that he must also address himself to the minds of his audience before they could hear him. He never made any concessions to them, and as a result they made none to him. He sought to project his inner enthusiasm on to the public, but chose one method after another that ensured that his audience would regard his enthusiasms, not as inspiration, but as mere eccentricity or worse. Blake scholars disagree on whether or not Blake was a mystic. In the Norton Anthology, he is described as "an acknowledged mystic, [who] saw visions from the age of four".4 Frye, however, who seems to be one of the most influential Blake scholars, disagrees, saying that Blake was a visionary rather than a mystic. "'Mysticism' . . . means a certain kind of religious techniques difficult to reconcile with anyone's poetry," says Frye. 5 He next says that "visionary" is "a word that Blake uses, and uses constantly" and cites the example of Plotinus, the mystic, who experienced a "direct apprehension of God" four times in his life, and then only with "great effort and relentless discipline." He finally cites Blake's poem "I rose up at the dawn of day," in which Blake states, I am in God's presence night & day, And he never turns his face away. Besides all of these achievements, Blake was a social critic of his own time and considered himself a prophet of times to come. Frye says that "all his poetry was written as though it were about to have the immediate social impact of a new play". 6 His social criticism is not only representative of his own country and era, but strikes profound chords in our own time as well. As Appelbaum said in the introduction to his anthology English Romantic Poetry, "[Blake] was not fully rediscovered and rehabilitated until a full century after his death". For Blake was not truly appreciated during his life, except by small cliques of individuals, and was not well-known during the rest of the nineteenth century.7 3 Murry, John Middleton - William Blake. [London, Jonathan Cape, 1933.] (p.12.) Mack, Maynard (ed.) - "William Blake" in The Norton Anthology: World Masterpieces, Expanded Edition, Volume 2. [New York: Norton, 1995.] (p. 783.) 5 Frye, Northrop - Fearful Symmetry: A Study of William Blake. [Boston, Beacon Press, 1967.] (Chpt. 8.) 6 c.a. (Chpt. 4.) 7 Appelbaum, Stanley - Introduction to English Romantic Poetry: An Anthology. [Mineola, Dover, 1996.] (Chpt. V.) 4 Chapter I. – William Blake 6 Blake's life might seem uneventful, but his inner life was so exciting that it did not matter. His enthusiasm lifted him out of London into Jerusalem - or rather, brought Jerusalem into London and turned a rainbow over Hyde Park into a gateway to heaven. Blake's enthusiasm are not the toad-like crazes of a perpetually unsatisfied man, but the developing insights of someone with a wide-ranging mind responding to life's rejections of his hopes, not by losing hope, but by rebuilding it. And each stage has its own artistic correlative. Blake was born November 28, 1757, in London. His father was a hosier living in Broad Street in the Soho district of London, where Blake lived most of his life. He was the second son of a family of four boys and one girl. Only his younger brother Robert was of great significance in William's life, as he was the one to share his devotion to the arts.8 William grew up in London and later described the visionary experiences he had as a child in the surrounding countryside, when he saw angels in a tree at Peckham Rye and the prophet Ezekiel in a field. William very soon declared his intention of becoming an artist in 1767, and was allowed to leave ordinary school at the age of ten to join a drawing school and started to attend the drawing school of Henry Pars in the Strand. He educated himself by wide reading and the study of engravings from paintings by the great Renaissance masters. Here he worked for five years, but, when the time came for an apprenticeship, his father was unable to afford the expense of his entrance to a painter's studio. A premium of fifty guineas, however, enabled him, aged nearly fifteen, to enter on 4 August 1772 the workshop of a masterengraver, James Basire. There, in Great Queen Street, Lincoln's Inn Fields, he worked faithfully for seven years, learning all the techniques of engraving, etching, stippling and copying. This thorough training equipped him as a man who could later claim with justice that he was one of the finest craftsmen of his time, one moreover able not only to develop and improve the conventional modes throughout his life, but also to invent methods of his own. Basire sent him to make drawings of the sculptures in Westminster Abbey, and thus awakened his interest in Gothic art.9 8 Keynes, Geoffrey - William Blake: Songs of Innocence and of Experience. [New York: Oxford University Press, 1967.] ("An Introduction to William Blake") 9 Wilson, Mona - The Life of William Blake. [(ed.) Geoffrey Keynes. London, Oxford University Press, 1971.] Chapter I. – William Blake 7 On completion of his apprenticeship in 1779 Blake entered the Royal Academy as an engraving student. His period of study there seems to have been stormy. He took a violent dislike to Sir Joshua Reynolds, then president of the Royal Academy, rebelling against his aesthetic doctrines, and felt that his talents were being wasted. He was initially influenced by the engravings he studied of the works of Michelangelo and Raphael. He made drawings from the antique in the conventional manner and some life studies, though he soon rejected this form of training, saying that 'copying nature' deadened the force of his imagination. For the rest of his life he exalted imaginative art above all other forms of artistic creation, scarcely any of his productions being strictly representational. While still at the Academy he was earning his living by engraving for publishers and was also producing independent watercolours. At this time his friends included the "roman group" of brilliant young artists, among them the sculptor John Flaxman and the painter Thomas Stothard.10 He also came into contact with the highly original Romantic painter Henry Fuseli at this time, whose work may have influenced him. He began his career as an engraver and artist, and was an apprentice to Henry Fuseli for a time. He then became deeply impressed with the work of his contemporary figurative painters like James Barry, John Mortimer, and Henry Fuseli, who, like Blake, depicted dramatically posed nude figures with strongly rhythmic, linear contours. Fuseli's extravagant pictorial fantasies in particular freed Blake to distort his figures to express his inner vision.11 In 1784 he set up a print shop; although it failed after a few years, for the rest of his life Blake eked out a living as an engraver and illustrator.12 In the late 1760s and '70s the "roman group" circle of British painters in Rome had already begun to find academic precepts inadequate. James Barry, the brothers John and Alexander Runciman, John Brown, George Romney, and the Swiss-born Henry Fuseli favoured themes – whether literary, historical, or purely imaginary – determined by a taste for the pathetic, bizarre, and extravagantly heroic. Mutually influential and highly eclectic, they combined, especially in their drawings, the linear tensions of Italian Mannerism with bold contrasts of light and shade. Though never in Rome, John Hamilton Mortimer had much in common with this group, for all were participants in a move to found a national school of 10 Wilson, Mona - The Life of William Blake. [(ed.) Geoffrey Keynes. London, Oxford University Press, 1971.] Bindman, David - Blake as an Artist. [Oxford, Phaidon, 1977.] (p. 53-56.) 12 Lindsay, Jack - William Blake: His Life and Work. [London, Constable, 1978.] 11 Chapter I. – William Blake 8 narrative painting. Fuseli's affiliations with the German Romantic Sturm und Drang writers predisposed him, like Flaxman, toward the "primitive" heroic stories of Homer and Dante. Flaxman himself, in the two-dimensional linear abstraction of his drawings, a twodimensionality implying rejection of Renaissance perspective and seen for instance in the expressive purity of "Penelope's Dream" (1792-93), had important repercussions throughout Europe. Both Fuseli and Flaxman highly influenced both Blake's interest in mythology and the heroic and also his attitude towards art.13 William Blake absorbed and outstripped the Fuseli circle, evolving new images for a unique private cosmology, rejecting oils in favour of tempera and watercolour, and depicting, as in "Pity" (1795), a shadowless world of soaring, supernatural beings. His passionate rejection of rationalism and materialism, his scorn for both Sir William Blake – Pity Joshua Reynolds and the Dutch Naturalists, stemmed from a conviction that "poetic genius" could alone perceive the infinite, so essential to the artist since "painting, as well as poetry and music, exists and exults in immortal thoughts." 14 In his painting, (as well as in his poetry), Blake seemed to most of his contemporaries to be completely out of the artistic mainstream of their time. His art was in fact far too adventurous and unconventional to be easily accepted in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. He has been called a pre-romantic because it was not only in poetry that he rejected neoclassical literary style and modes of thought, his graphic art too defied 18th-century conventions. Always stressing imagination over reason, he felt that ideal forms should be constructed not from observations of nature but from inner visions. His rhythmically patterned linear style is also a repudiation of the painterly academic style. Blake's attenuated, fantastic figures go back, instead, to the medieval tomb statuary he copied as an apprentice and to 13 14 Bindman, David - William Blake, His Art and Times. [Thames and Hudson, 1982.] (p. 15-23.) c.a. (p. 45.) Chapter I. – William Blake 9 Mannerist sources. The influence of Michelangelo is especially evident in the radical foreshortening and exaggerated muscular form in one of his best-known illustrations, popularly known as The Ancient of Days, the frontispiece to his poem Europe, a Prophecy (1794).15 For this reason Blake remained virtually unknown until Alexander Gilchrist's biography was published in 1863, and he was not fully accepted until his remarkable modernity and his imaginative force, both as poet and artist, were recognized in the twentieth century. 16 In spite of this his paintings belong to a recognizable artistic tradition, that of English figurative painting of the later 18th century. Throughout his life Blake stressed the superiority of line, or drawing, over colour, commending the "hard wirey line of rectitude." He condemned everything that he felt made painting indefinite in contour, such as painterly brushwork and shadowing. Finally, Blake stressed the primacy of art created from the imagination over that drawn from the observation of nature. The figures in Blake's many prints and watercolour and tempera paintings are notable for the rhythmic vitality of their undulating contours, the monumental simplicity of their stylised forms, and the dramatic effectiveness and originality of their gestures. He also showed himself a daring and unusually subtle colourist in many of his works. Much of Blake's painting was on religious subjects: illustrations of the work of John Milton, his favourite poet (although he rejected Milton's Puritanism), for John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress, and for the Bible, including 21 illustrations to the 'Book of Job'. Blake's favourite subjects were episodes from the Bible, along with episodes found in the works of Milton and Dante. Among his secular illustrations were those for an edition of Thomas Gray's poems and the 537 watercolours for Edward Young's Night Thoughts - only 43 of which were published. His illustrations for the Book of Job were done late in life, and they mark the summit of his achievement in the visual arts.17 15 Blunt, Anthony - The Art of William Blake. [Columbia University Press, New York, 1963.] (p. 78.) Keynes, Geoffrey - William Blake: Songs of Innocence and of Experience. [New York: Oxford University Press, 1967.] ("An Introduction to William Blake") 17 Blunt, Anthony - The Art of William Blake. [Columbia University Press, New York, 1963.] (p. 12.) 16 Chapter I. – William Blake 10 The spiritual, symbolical expression of Blake's complex sympathies, his ability to recognize God in a single blade of grass, inspired Samuel Palmer, who, with his friend Edward Calvert, extracted from nature a visionary world of exquisite, though short-lived, intensity.18 On August 18, 1782, Blake married a poor, illiterate girl, Catherine Boucher, who was to make a perfect companion for him. Having married, Blake left his father's home and rented a small house round the corner in Poland Street, being joined there by his brother Robert after their father's death in 1784. William then began to train Robert as an artist. Meanwhile he himself, self-educated, had already acquired a wide knowledge of poetry, philosophy and general literature, and was ready to take his place among people of intelligence. He attended social gatherings of intellectuals, to whom he even communicated his own poems, sometimes singing them to tunes of his own composition.19 Flaxman introduced him to the Rev. Anthony S. Mathew and his wife, and for a time Blake was one of the chief attractions at their literary parties. Flaxman and Mathew paid for the printing of a collection of verses by their young friend, Poetical Sketches (1783). A preface provides the information that the verses were written between Blake's 12th and 20th years. This is a remarkable first volume of poetry, and some of the poems contained in it have a freshness, a purity of vision, and a lyric intensity unequaled in English poetry since the 17th century.20 Blake's visits to the Mathews' eventually became less frequent and finally ceased. Nevertheless, in the 1780s he was one of a group of progressive-minded people that met at the house of Blake's employer, the Radical bookseller Joseph Johnson. His mind was developing an unconventional and rebellious quality, acutely conscious of any falsity and pomposity in others, so that about 1784 or 1787 he wrote a burlesque novel, known as An Island in the Moon, in which he ridiculed contemporary manners and conventions, and in which members of this group are satirized. In 1784, after his father's death, Blake started a print shop in London and took his younger brother Robert to live with him as assistant and pupil. Early in 1787 Robert fell ill and in February he died; and William, who had nursed him devotedly, later said that he had seen Robert's soul joyfully rising through the ceiling. At the moment of Robert's death his 18 c.a. (p. 34.) Keynes, Geoffrey - William Blake: Songs of Innocence and of Experience. [New York: Oxford University Press, 1967.] ("An Introduction to William Blake") 20 Lindsay, Jack - William Blake: His Life and Work. [London, Constable, 1978.] 19 Chapter I. – William Blake 11 visionary faculty enable him to see "the released spirit ascend heavenwards, clapping its hands for joy".21 For the rest of his life William claimed that he could communicate with this brother's spirit and gain strength from his advice. He also said that Robert had appeared to him in a vision and revealed a method of engraving the text and illustrations of his books without having recourse to a printer. This method was Blake's invention of what he called "illuminated printing," in which, by a special technique of relief etching, each page of the book was printed in monochrome from an engraved plate containing both text and illustration: an invention foreshadowed by his friend, George Cumberland. Although his method of illuminated printing is not completely understood, the most likely explanation is that he wrote the words – not in reversed script, as an engraver must normally do – and drew the pictures for each poem on a copper plate, using some liquid impervious to acid, which when applied left text and illustration in relief. After etching away the unwanted material, the plate became one large piece of type, to be inked and printed on his engraver's press. Ink or a colour wash was then applied, and the printed picture was finished by hand in watercolours. Thus each print is itself a unique work of art. As an artist Blake broke the ground that would later be cultivated by the Pre-Raphaelites. Most of Blake's works after the Poetical Sketches were engraved and "published" in this way, and so reached only a limited public during his lifetime. Today these "illuminated books," with their dynamic designs and glowing colours, are among the world's art treasures. Most of Blake's paintings (such as "The Ancient of Days" or the frontispiece to Europe: a Prophecy) are actually prints too made from copper plates, which he etched in his 'illuminated printing' method. The product of his first enthusiasm is the foundation of all the rest; it reveals him, not as the preacher of doctrines of free innocence, or as a mystical thinker, but as that typical eighteen-century figure, the inventor. In other hands his invention might well have succeeded: the re-creation in modern guise of the medieval illuminated book, text and design together as unity, but using new techniques to make reproduction feasible. Illustrated books were much in demand, but not easy to produce. Blake was writing poetry; how better to see it published than in the style of medieval illuminated book, a hand-made, unique work of art? As a poet 21 Keynes, Geoffrey - William Blake: Songs of Innocence and of Experience. [New York: Oxford University Press, 1967.] ("An Introduction to William Blake") Chapter I. – William Blake 12 and artist, he could create the whole work, and the result would be as fine as an illustrated manuscript. But there was no need for the work to remain unique; as an engraver he had the skill and the means to make multiple copies. Many of the plates, especially in the Songs, America and Europe, fulfil his hopes and make one artistic unity, poem and design.22 In his readiness to invent new techniques, Blake was typical of his age. His "illuminated books" were usually coloured with watercolour or printed in colour by Blake and his wife, bound together in paper covers, and sold for prices ranging from a few shillings to 10 guineas. He must have thought his fortune was made. True, it was a clumsy process by our standards, and did not produce a very well-defined or legible text, but it satisfied Blake's needs, and he used it as long as he wrote poetry. It might well have made him a success, if he had produced works that the public wanted to see. But apart from Songs of Innocence, a children's poetry book which might well have found a market, he used it almost entirely for his own ideological campaign. Even this might have succeeded – Shelley found an audience – but Blake's books used an idiom that even his friends found hard to understand. William Blake created a unique form of illustrated verse; his poetry, inspired by mystical vision, belongs to the most original lyric and prophetic poetry in the language. His poetry and visual art are inextricably linked, therefore to fully appreciate one you must see it in context with the other. As was to be Blake's custom, he illustrated the Songs with designs that demand an imaginative reading of the complicated dialogue between word and picture. 23 You could say, he was one of those 19th century figures who could have and should have been "beatniks", along with Rimbaud, Verlaine, Manet, Cézanne and Whitman. The first books in which Blake made use of his new printing method were two little tracts, There is No Natural Religion and All Religions are One, engraved about 1788. They contain the seeds of practically all the subsequent development of his thought. In them he boldly challenges accepted contemporary theories of the human mind derived from Locke and the prevailing rationalistic-materialistic philosophy and proclaims the superiority of the imagination over other "organs of perception," since it is the means of perceiving "the Infinite," or God. Immediately following these tracts came Blake's first masterpieces, in an astonishing outburst of creative activity: Songs of Innocence and The Book of Thel (both 22 Bindman, David - Blake as an Artist. [Oxford, Phaidon, 1977.] (p.58.) Mitchell, W.J.T. - Blake's Composite Art: A Study of the Illuminated Poetry. [Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1978.] (p. 13.) 23 Chapter I. – William Blake 13 engraved 1789), The French Revolution (1791), The Marriage of Heaven and Hell and Visions of the Daughters of Albion (both engraved 1793), and Songs of Innocence and Experience (1794). The production of these works coincided with the outbreak of the French Revolution, of which Blake, like the other members of the group that met at Johnson's shop, was at first an enthusiastic supporter. Blake significantly differed from other English revolutionaries, however, in his hatred of deism, atheism, and materialism, and his profound, though undogmatic, religious sense.24 Blake did, however, approve of some of the measures that individuals and societies took to gain and maintain individual freedom. As Appelbaum said, "He was liberal in politics, sensitive to the oppressive government measures of his day, [and] favorably inspired by the American Revolutionary War and the French Revolution".25 This is the time when Blake keeps an intensive communication with the revolutionary American political thinker Thomas Paine. According to Keynes, Blake wrote many positive and appreciative things about him, for instance, such as "The Bishop never saw the Everlasting Gospel any more than Tom Paine".26 As "London" shows, however, Blake did not entirely approve of the measures taken to forward the causes he longed to advance: "London" refers to how the "hapless Soldier's sigh/ runs in blood down Palace walls" ["London" 791]. Among many other events which took place during the French Revolution, this could possibly refer to the storming of the Bastille or the executions of the French nobility. Blake began writing poetry at the age of 12, and his first printed work, Poetical Sketches (1783), is a collection of youthful verse. Amid its traditional, derivative elements are hints of his later innovative style and themes. As with all his poetry, this volume reached few contemporary readers. Blake's most popular poems have always been Songs of Innocence (1789). These lyrics are notable for their eloquence. In 1794, disillusioned with the possibility of human perfection, Blake issued Songs of Experience, employing the same lyric style and much of the same subject matter as in Songs of Innocence. Both series of poems take on deeper resonances when read in conjunction. Innocence and Experience, “the two contrary states of the human soul,” are contrasted in such companion pieces as “The Lamb” and “The Tyger.” 24 Bindman, David - William Blake, His Art and Times. [Thames and Hudson, 1982.] (p. 45-50.) Appelbaum, Stanley - Introduction to English Romantic Poetry: An Anthology. [Mineola, Dover, 1996.] (Chpt. V.) 26 Damon, S. Foster. - A Blake Dictionary: The Ideas and Symbols of William Blake. [New York, Dutton, 1971.] (p. 318.) 25 Chapter I. – William Blake 14 Blake's subsequent poetry develops the implication that true innocence is impossible without experience, transformed by the creative force of the human imagination. Songs of Innocence is Blake's first masterpiece of "illuminated printing." Blake made the twenty-seven plates of Songs of Innocence, dating the title page 1789, and thus initiated the series of his now famous Illuminated Books. The impulse to produce his poems in this form was partly due to his cast of mind, whereby the life of the imagination was more real to him than the material world. This philosophy demanded the identification of ideas with symbols which could be translated into visual images – word and symbol each reinforcing the other. His lyrical poems have content enough to make them acceptable without the visual addition, but he did not choose that they should be read in this plain shape, and consequently his output of books reckoned in numbers of copies was always very limited. Songs of Innocence differs radically from the rather derivative pastoral mode of the Poetical Sketches. In the Songs, Blake took as his models the popular street ballads and rhymes for children of his own time, transmuting these forms by his genius into some of the purest lyric poetry in the English language. There is no reason for thinking that when he composed the Songs of Innocence he had already envisaged a second set of antithetical poems embodying Experience. The Innocence poems were the products of a mind in a state of innocence and of an imagination unspoiled be stains of worldliness. Public events and private emotions soon converted Innocence into Experience, producing Blake's preoccupation with the problem of Good and Evil. This, with his feelings of indignation and pity for the sufferings of mankind as he saw them in the streets of London, resulted in his composing the second set. So in 1794 he finished a slightly rearranged version of Songs of Innocence with the addition of Songs of Experience; the double collection, in Blake's own words in the subtitle, "shewing the two contrary states of the human soul." The "two contrary states" are innocence, when the child's imagination has simply the function of completing its own growth; and experience, when it is faced with the world of law, morality, and repression. Songs of Experience provides a kind of ironic answer to Songs of Innocence. The earlier collection's celebration of a beneficent God is countered by the image of him in Experience, in which he becomes the tyrannous God of repression. The key symbol of Innocence is the Lamb, the corresponding image in Experience is the Tyger.27 27 Mack, Maynard (ed.) - "William Blake" in The Norton Anthology: World Masterpieces, Expanded Edition, Volume 2. [New York: Norton, 1995.] (p.784.) Chapter I. – William Blake 15 The Tyger in this poem is the incarnation of energy, strength, lust, and cruelty, and the tragic dilemma of mankind is poignantly summarized in the final question, "Did he who made the Lamb make thee?" Blake also viewed the larger society, in the form of contemporary London, with agonized doubt in Experience, in contrast to his happy visions of the city in Innocence. In the great poem "London," which has been described as summing up many implications of Songs of Experience, Blake describes the woes that the Industrial Revolution and the breaking of the common man's ties to the land have brought upon him. "London" is an especially powerful indictment of the new "acquisitive society" then coming into being, and the poem's naked simplicity of language is the perfect medium for conveying Blake's anguished vision of a society dominated by money.28 When Blake's first great enthusiasm gripped him, the world was in the ferment of revolution. But Blake was convinced that art, the works of the imagination, not political revolution, were the key to its renovation. In the first group of legends (1789-93), Blake presents his case: the indestructibility of innocence. The soul that freely follows its imaginative instincts will be innocent and virtuous; nature protects this innocence and the only sin is to allow one's nature to be prevented by law and custom. Free love is only true love; law destroys both love and freedom.29 Some see him as true nonconformist radical who numbered among his associates such English freethinkers as Thomas Paine and Mary Wollstonecraft.30 But for Blake freedom could not come about except through the imagination. The Bible presented a view, not of freedom, love, innocent happiness and above all, imagination, but law. The world's images were all wrong. Blake would put it right with a series of narrative poems in the new medium, to illustrate the nature of imaginative truth. Poems such as ‘The French Revolution’ (1791), ‘America’, a ‘Prophecy’ (1793), ‘Visions of the Daughters of Albion’ (1793), and ‘Europe, a Prophecy’ (1794) express his condemnation of 18th-century political and social tyranny. Political revolution was not in itself the antidote to tyranny, but a symptom of mankind's awakening to the freedom of the spirit. In the exercise of the imagination, the purity and inviolability of 28 Mack, Maynard (ed.) - "William Blake" in The Norton Anthology: World Masterpieces, Expanded Edition, Volume 2. [New York: Norton, 1995.] (p.785.) 29 Varanyi Szilvia - Sin and Error in William Blake . [Budapest, ELTE-BTK DELL, Szakdolgozat 19xx.] 30 Erdman, David V. – Blake: Prophet against Empire. [Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977.] (p. 45.) Chapter I. – William Blake 16 innocence would reveal itself. The need for law, and tyranny itself, would not wither at the hand of war, but at the breath of the free imagination. Theological tyranny is one subject of The Book of Urizen (1794), and the dreadful cycle set up by the mutual exploitation of the sexes is vividly described in ‘The Mental Traveller’ (circa 1803).31 These books, including the Songs of Experience (1794), are devoted to discovering what had gone wrong. Typically Blake did not reject his beliefs, but went on to improve them. Now he understood that it was too simple to see the world's problems as the hostility of evil minds against good - the tyrant threatening the innocent imagination. His new visions emerged in his enthusiasm for the plan of a great epic, Vala, which he started writing on the black proofs of his Night Thoughts designs.32 Among the Prophetic Books is a prose work, ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’ (1790-93), which develops Blake's idea that “without Contraries is no progression.” It includes the “Proverbs of Hell,” such as “The tygers of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction.” Blake was experimenting in narrative as well as lyrical poetry at this time. Tiriel, a first attempt, was never engraved. The Book of Thel, with its lovely flowing designs, is an idyll akin to Songs of Innocence in its flowerlike delicacy and transparency. In Tiriel and The Book of Thel Blake uses for the first time the long unrhymed line of 14 syllables, which was to become the staple metre of his narrative poetry.33 The fragment called The French Revolution is a heroic attempt to make epic poetry out of contemporary history. In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell satire, prophecy, humour, poetry, and philosophy are mingled in a way that has few parallels. Written mainly in terse, sinewy prose, it may be described as a satire on institutional religion and conventional morality. In it Blake defines the ideal use of sensuality: "If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, infinite." Blake reverses the tenets of conventional Christianity, equating the good with reason and repression and regarding evil as the natural expression of a fundamental psychic energy.34 As Appelbaum said of Blake, "Blake replaced the arid atheism or tepid 31 Nurmi, Martin K. - William Blake. [London, Hutchinson, 1975.] (p. 54.) Lindsay, Jack - William Blake: His Life and Work. [London, Constable, 1978.] (p. 79.) 33 c.a. (p. 124.) 34 Damon, S. Foster. - A Blake Dictionary: The Ideas and Symbols of William Blake. [New York, Dutton, 1971.] (Chpt. XI.) 32 Chapter I. – William Blake 17 deism of the encyclopaedists and their disciples with a glowing new personal religion".35 Besides rejecting "arid atheism" and "tepid deism," Blake also attacked conventional religion. In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell he wrote "Prisons are built with stones of Law, Brothels with bricks of Religion" and "As the caterpillar chooses the fairest leaves to lay her eggs on, so the priest lays his curse on the fairest joys" ["Proverbs" 19; "Proverbs" 20]. Rather than accepting a traditional religion from an organized church, Blake designed his own mythology to accompany his personal, revealed religion. Blake's personal religion was an outgrowth of his search for the Everlasting Gospel, which he believed to be the original, pre-Jesus revelation which Jesus preached. As Blake said, "all had originally one language and one religion: this was the religion of Jesus, the everlasting Gospel. Antiquity preaches the Gospel of Jesus". Blake's religion was based upon the joy of man, which he believed glorified God. The Marriage of Heaven and Hell culminates in the "Song of Liberty," a hymn of faith in revolution, ending with the affirmation that "everything that lives is Holy."36 The book includes a famous criticism of Milton and the "Proverbs of Hell," 70 pithy aphorisms that are notable for their praise of heroic energy and their sense of creative vitality. In Visions of the Daughters of Albion Blake develops the theme of sexual freedom suggested in several of the Songs of Experience. The central figure in the poem, Oothoon, finds that she has attained to a new purity through sexual delight and regeneration. In this poem the repressive god of abstract morality is first called Urizen. About 1789 Blake and his wife had moved to a small house on the south side of the Thames in a terrace called Hercules Buildings, Lambeth. They lived there for seven years, and this, the period of Blake's greatest worldly prosperity, was also that of his deepest spiritual uncertainty. Here 35 Appelbaum, Stanley - Introduction to English Romantic Poetry: An Anthology. [Mineola, Dover, 1996.] (Chpt. III.) 36 Damon, S. Foster. - A Blake Dictionary: The Ideas and Symbols of William Blake. [New York, Dutton, 1971.] (p. 344.) Chapter I. – William Blake 18 he set about making a number of books embodying his philosophical system, which he expressed in an increasingly obscure form. These have become known as his Prophetic Books, their production going on at the same time as he was painting numbers of pictures and making large colour prints, using a tempera medium instead of oil paints for the former. In the Prophetic Book – America, A Prophecy (1793), Europe, A Prophecy (1794), The Book of Urizen (1794), The Book of Ahania, The Book of Los, and The Song of Los (all 1795) – Blake elaborates a series of cosmic myths and epics through which he sets forth a complex and intricate philosophical scheme. A principal symbolic figure in these books is Urizen, a spurned and outcast immortal who embodies both Jehovah and the forces of reason and law that Blake viewed as restricting and suppressing the natural energies of the human soul.37 The Prophetic Books describe a series of epic battles fought out in the cosmos, in history, and in the human soul, between entities symbolizing the conflicting forces of reason (Urizen), imagination (Los), and the spirit of rebellion (Orc). America, illustrated with brilliantly coloured designs, is a powerful short narrative poem giving a visionary interpretation of the American Revolution as the uprising of Orc, the spirit of rebellion. Europe shows the coming of Christ and the French Revolution of the late 18th century as part of the same manifestation of the spirit of rebellion. The Book of Urizen is Blake's version of the biblical Book of Genesis. Here the Creator is not a beneficent, righteous Jehovah, but Urizen, a "dark power" whose rebellion against the primeval unity leads to his entrapment in the material world. The poetry of The Book of Urizen, written in short unrhymed lines of three accents, has a gloomy power, but is inferior in effect to the magnificent accompanying designs, which have an energy and monumental grandeur anticipating the quality of those of Jerusalem, Blake's most splendid illuminated book. Blake's saga of myths is continued in The Book of Ahania, a kind of Exodus following the Genesis of Urizen, and in The Book of Los. In The Song of Los Blake returns to the cosmic theme and brings the story of humanity down to his own time. By this time Blake seems to have reached his spiritual nadir, and his poetry peters out in the last of the Prophetic books. He had lost faith in the French Revolution as an apocalyptic and regenerating force, and was finding his attempt at a synthesis based on the 37 Lindsay, Jack - William Blake: His Life and Work. [London, Constable, 1978.] Chapter I. – William Blake 19 "contraries" of good and evil inadequate as an answer to the complexities of human existence.38 Blake was in many ways typical of his age and like William Morris seventy years later, he was just as typical in his fascination with the medieval. Gothic stories and melodramas of castles, knights and monks and fair ladies were already popular enough for Jane Austen to parody in Northanger Abbey. Matthew Lewis's notorious soft-porn The Monk sold very well indeed. Scott, not Wordsworth, became the favourite poet of the age.39 Blake, unfortunately for him, was captured, not by the clarity and humour of Chaucer, much as he admired him, but by the cloudy pseudo-medievalism of Chatterton and Ossian.40 This kind of writing is most suitable for escapist literature, but Blake used it for most of his work in 'illuminated printing', to convey his most urgent messages. Apart from the Songs (1789-94), virtually all his completed books are such gothic legends. Grandiose, superhuman figures gesticulate across his pages; and since they crowd past, not to entertain us but to evangelise, bearing names we have never heard of and associations we can slowly grasp, it is not surprising that Blake's major poetry, far from bringing him fame, brought only ridicule. When later he added to his myth the fumblings of antiquaries – notably the theories of William Stukeley – who identified Eastern religions with ancient Britain, linked the Syrian mother-goddess with Avebury and the Druids with the biblical patriarchs, even his best friends found it almost impossible to follow his imaginative fights; and so do we.41 In his so-called Prophetic Books, a series of longer poems written from 1789 on, Blake created a complex personal mythology and invented his own symbolic characters to reflect his social concerns. A true original in thought and expression, he declares in one of these poems, “I must create a system or be enslaved by another man's.” With The Song of Los the experimental period of his poetic career ended: he engraved no more books for nearly 10 years. In 1795 he had been commissioned by a bookseller to make designs for an edition of Edward Young's Night Thoughts. He worked on this until 1797, producing 537 watercolour drawings. It seems to have been while he was working on these illustrations that a fresh creative impulse led to the beginning of his first full-scale epic poem. 38 Damon, S. Foster. - A Blake Dictionary: The Ideas and Symbols of William Blake. [New York, Dutton, 1971.] Appelbaum, Stanley - Introduction to English Romantic Poetry: An Anthology. [Mineola, Dover, 1996.] (Chpt. I.) 40 Phillips, Michael (ed.) - Interpreting Blake. [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.] (p. 193.) 41 Fisher, F. Peter - Blake and the Druids . [in Frye (ed.): Blake . Prentice-Hall, New Jersey 1966.] 39 Chapter I. – William Blake 20 The first draft of the epic, called Vala, was begun in 1795. He worked on it for about nine years, during which period he rewrote it under the title of The Four Zoas, but never engraved it. It remains a magnificent torso, but the quality of this work's poetry and its thought are obscured by its overly complicated mythological scheme. In spite of the grandeur of individual passages and of the major conception, The Four Zoas remains fragmentary and lacking in coherence. It provided the materials out of which Blake constructed his later epics, Milton and Jerusalem. 42 In 1800, at the invitation of William Hayley, a Sussex squire, Blake and his wife went to live in a cottage provided by Hayley at Felpham on the Sussex coast, where he lived and worked until 1803 under the patronage of Hayley. There he experienced profound spiritual insights that prepared him for his mature work, the great visionary epics written and etched between about 1804 and 1820. Milton (1804-08), Vala, or The Four Zoas (that is, aspects of the human soul, 1797; rewritten after 1800), and Jerusalem (1804-20) have neither traditional plot, characters, rhyme, nor meter; the rhetorical free-verse lines demand new modes of reading. They envision a new and higher kind of innocence, the human spirit triumphant over reason. In his new vision of the ideal world, all beings are united in one perfect Human Form. After the Fall - which as always in Blake is a failure of the imagination - the Human is fragmented, and hostility arises between his now separated elements. None of these elements is perfectly good or evil; the creatures of the earlier myth, Orc, Urizen and Los, are now all damaged pieces of the Universal Human Form, and none will be complete without the rest. From this time on, Urizen, the great evil of America (1793), becomes less hated and more pitied. Even Vala, the female form who is at first blamed for the disintegration, is at last regenerated.43 William Hayley, a well-meaning, obtuse dilettante, who had employed Blake to make engravings, regarded his imaginative works with contempt and tried to turn him into a miniature painter and tame poet on his estate. At first Blake was delighted with life in Sussex, but he soon found the patronizing Hayley intolerable. The cottage was damp and Mrs. Blake's health suffered, and in 1803 the Blake returned to London. Toward the end of his stay at Felpham, Blake was accused by a soldier called Schofield of having uttered seditious words when he had ejected him from his cottage garden. He was tried at the quarter sessions at 42 43 Lindsay, Jack - William Blake: His Life and Work. [London, Constable, 1978.] Damon, S. Foster. - William Blake: His Philosophy and Symbols. [Gloucester, Mass.: Peter Smith, 1958.] Chapter I. – William Blake 21 Chichester, denied the charges, and was acquitted. Hayley gave bail for Blake and employed counsel to defend him. This experience became part of the mythology underlying Jerusalem and Milton. 44 It was also probably at Felpham that Blake wrote the most notable of his later lyrical poems, including "Auguries of Innocence", with its memorable opening stanza: To see a World in a Grain of Sand And a Heaven in a Wild Flower, Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand And Eternity in an hour. It was at Felpham, too, that he wrote some of his finest letters, many of them addressed to Thomas Butts, a government clerk who was for years a generous and loyal supporter and patron of Blake and who commissioned almost his total output of paintings and watercolours at this period. In 1804-08 Blake engraved Milton. This poem is a comparatively brief epic, which deals with a contest between the hero (Milton) and Satan; it too is couched in the prophetic grandeur and obscurity of Blake's invented mythology. Milton's struggle with evil in the poem is a reflection of Blake's own conflicts with the domineering patronage of William Hayley. Jerusalem is Blake's third major epic and his longest poem. Begun about 1804, and written and engraved soon after the completion of Milton, it is also the most richly decorated of Blake's illuminated books, and only a few of its 100 plates are without illustration. Although the details are complex and present many difficulties, the poem's main outlines are simple. At the opening of the poem the giant Albion (who represents both England and humanity) is shown plunged into the "Sleep of Ulro," or the hell of abstract materialism. The core of the poem describes his awakening and regeneration through the agency of Los, the archetypal craftsman or creative man. The poem's consummation is the reunion of Albion with Jerusalem (his lost soul) and with God through his acceptance of Jesus' doctrine of universal brotherhood.45 44 45 Wilson, Mona - The Life of William Blake. [(ed.) Geoffrey Keynes. London, Oxford University Press, 1971.] Lindsay, Jack - William Blake: His Life and Work. [London, Constable, 1978.] Chapter I. – William Blake 22 During Blake's Felpham years another enthusiasm arrived, close on the heels of the Immortal Man. It is a time once more for the restatement of the vision and the third development of the myth, not this time through disillusionment but because his images had taken a new colouring. Markedly Christian language begins to creep into Vala, which eventually collapses under the strain. Even before Felpham, Blake has used the phrase, "We who call ourselves Christians". Now the belief grows into its own images which must be incorporated into the myth. It is a complex development. The Druids of Ancient Britain are identified with the patriarchs of the Bible, and the Giant Albion - the Spirit of Britain - is identified with the Israel of the Bible. Thus Albion is the Holy Land, London is Jerusalem, and Jesus did indeed walk (in the truth of the imagination) across these hills. The solution to the disintegration of man is reconciliation through forgiveness, and the reconciliation of Christ and Albion brings about the reunion of the disintegrated Eternal Human, who appears then as Christ himself. It is not enough now, as in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, to find one's own imaginative life. The Human Form Divine will not be re-created until the whole nation, the whole of mankind, the whole universe, is drawn together; but this can begin in the smallest of single actions. Blake has returned to the idealistic hope of America, but now his thought is less simple and more mystical; yet as the pages of Jerusalem show, no less radical.46 Blake's life during the period from 1803 to about 1820 was one of worldly failure. He found it difficult to get work, and the engravings that can be identified as his from this period are often hack jobs. In 1809 he made a last effort to put his work before the public and held an exhibition of 16 paintings and watercolour drawings. He wrote a thoughtful Descriptive Catalogue for the exhibition, but only a few people attended. But after this long period of obscurity, Blake found in 1819 a new and generous patron in the painter John Linnell, who introduced him to a group of young artists among whom was Samuel Palmer. In his last years Blake became the centre of this group, whose members shared Blake's religious seriousness and revered him as their master. The most notable poetry Blake wrote after Jerusalem is to be found in The Everlasting Gospel (1818?), a fragmentary and unfinished work containing a challenging reinterpretation of the character and teaching of Christ. Blake's writings also include An Island in the Moon (1784), a rollicking satire on events in his early life; a collection of letters; and a notebook containing 46 Nathan, Norman - Prince William B. - The Philosophical Conceptions of William Blake. [Paris, Mouton, 1975.] Chapter I. – William Blake 23 sketches and some shorter poems dating between 1793 and 1818. It was called the Rossetti Manuscript, because it was acquired in 1847 by the English poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti, one of the first to recognize Blake's genius. But Blake's last years were devoted mainly to pictorial art. In 1821 Linnell commissioned him to make a series of 22 watercolours inspired by the Book of Job; these include some of his best known pictures. Linnell also commissioned Blake's designs for Dante's Divine Comedy, begun in 1825 and left unfinished at his death. These consist of 102 watercolours notable for their brilliant colour. Blake thus found in his 60s a following and support for the imaginative work he had longed to do all his life. As a result, it was in his last years that he produced his most technically assured and beautiful designs. Toward the end of his life Blake still coloured copies of his books while resting in bed, and that is how he died in a room off the Strand, in London, on the 12th August 1827, – in his 70th year – leaving uncompleted a cycle of drawings inspired by Dante's Divine Comedy. He was buried in an unmarked grave in Bunhill Fields. Blake is frequently referred to as a mystic, but this is not really accurate. He deliberately wrote in the style of the Hebrew prophets and apocalyptic writers. He envisioned his works as expressions of prophecy, following in the footsteps (or, more precisely strapping on the sandals) of Elijah and Milton. In his filthy London studio he succumbed to constant visions of angels and prophets who instructed him in his work. He once painted while receiving a vision of Voltaire, and when asked later whether Voltaire spoke English, replied: "To my sensations it was English. It was like the touch of a musical key. He touched it probably French, but to my ear it became English."47 It is the difficulty of Blake's visionary poetry, rather than the vividness that has captured the commentators. They have sought high and low in the mystical philosophies, or in the politics, of East and West for the "key" to his work. It is true that he has a habit of allusiveness that is certainly obscure. In the famous song, for example, England is 'clouded' by spiritual blindness more than by cumuli, and the 'Satanic mills' are the shackles of the mind, of which the Industrial Revolution is only one manifestation. The difficulty is not to be solved by finding a missing key. It is something less systematic; the problem of Blake himself. 47 Levi Asher - Literary Kicks on William Blake Chapter I. – William Blake 24 Each of Blake's new enthusiasm reshapes the legend of his poems. As Blake refines his beliefs, he refines his myth too. The function of Orc and Urizen in America (1793) is quite plain; one fights for freedom, the other for law. In The Book of Urizen (1794) it is much more complex, and by Vala (1803) and Milton (1810) they have had to be altered almost out of recognition, but they are never quite abandoned. Blake was not by instinct a narrative poet. He tended to 'improve' his longer poems by a process of accumulation rather than by following the demands of the narrative. His mind was like an untidy desk. He threw nothing away, and often used old material for new tasks. One never knows what one will find. The reader ploughing through pages full of 'dismal howling woe' comes across an unexpected line of startling beauty which only Blake could have written.48 It is therefore no use trying to understand Blake by means of a key. No one scheme fits all his works; each stage grows out of the one preceding it. Each enthusiasm gives a striking new turn to his legend and its imagery, but the new is always superimposed on the old. If we can understand the series of enthusiasms, we can begin to find our way through the difficulties of his work. It is easy to dismiss Blake as 'primitive', an artist whose attraction resides in his naivety, which is lost when the work becomes heavy and charmless. This is also too simple. There is an odd contradiction at the heart of Blake's writing. He repeatedly called for art to concern itself with the 'minute particulars' of life: "To generalise is to be an idiot!" he scribbled in the margin of Reynold's Discourses.49 On the other hand he criticized Wordsworth for paying too much attention to the details of nature at the expense of inner realities.50 More important, much of his poetry disregards his own rule. Words like 'howling' and 'dismal' appear far too often. His lyrics are usually marvels of conciseness, but he chose to express his dearest beliefs, not as 'minute particulars', but as cloudy, generalized figures representing eternal states of humanity. Milton ceases to be a seventeenth-century poet and becomes a state of Los, the eternal spirit of the imagination. From first to last, Blake champions the imagination, but too much misplaced convention. At his greatest, minutiae become eternal; at his worst, the eternal becomes a scheme.51 48 Phillips, Michael (ed.) - Interpreting Blake. [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.] (p. 114-116.) Lindsay, Jack - William Blake: His Life and Work. [London, Constable, 1978.] (p. 106.) 50 c.a. (p.112.) 51 Behrendt, Stephen C. - Reading William Blake. [London, Macmillan Press, 1992.] (p. 87.) 49 Chapter I. – William Blake 25 Here if anywhere else, lies the "key" to Blake. He was not a "Romantic" writer, whatever that is; he was neo-classic by training and inclination. He had no time for classical myth, but that is irrelevant. His instinct was to create – inspired by his own visions – not symbols out of mystical tradition, nor vivid observations of human life, but representative figures to embody both the inner nature of the subject and his own response to it. His long epic poems are made up of a mixture of inspiration, pig-headedness, evangelic fervour and profound imagery. When he failed, he became obscure or tedious – often both. When he succeeded, he created a kind of magic of which no other poet has been capable. He blundered into greatness, just as he often blundered away from it. Yet there are many occasions, as his mystical figures move across the abyss, when all the elements come together, and then he produces poetry of a unique kind of genius, which leave the reader in something more than admiration – in wonderment.