Session Seven Notes

advertisement

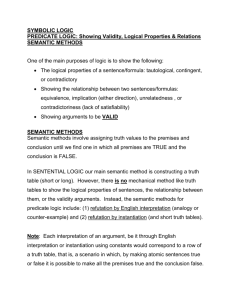

English 421 Semantics and Pragmatics Session Seven Notes Goals/Objectives: 1) To examine the mechanisms of language change 2) To examine the notion of polysemy 3) To examine the traditional categories of semantic change – narrowing, broadening, amelioration, and pejoration 4) To look briefly at the notions of metonymy and metaphor Semantic Change Questions/Main Ideas (Please write these down as Meaning change is everywhere, and no words are immune from it you think of them) A striking example of this is the English conjunction and It seems that this is such a simple and basic word that we would be same in assuming that its meaning should be the same thru history Semantic Change But this isn’t at all the case In pre-modern English, and was polysemous with ‘if’ Polysemy is the pattern where a single word has more than one meaning, that is, it possesses more than one distinct sense e.g. Chair = furniture, head of dept. Semantic Change The change can be exemplified by the following, from Shakespeare’s Love’s Labours Lost: ‘And I had but one penny in the world, thou shouldst have it to buy gingerbread’ The only possible reading of this sentence is: Semantic Change ‘If I had just one penny in the world …’ This polysemy has been lost in modern English But is shows that even elements of the vocabulary that one would think are conceptually the most basic, and hence the least likely to shift, can change their meaning Semantic Change Like many other branches of linguistics, the modern study of semantics began with a largely diachronic focus, investigating meaning change over time Knowledge of the history of Indo-European languages had sensitized scholars to the extreme fluidity of words’ meanings through time Semantic Change Traditional scholarly study of ancient languages in the nineteenth century (known as philology) meant that the details of meaning change in European languages were well known Semantic Change The availability of a long-written tradition, going back in the case of Greek to well before the sixth century BC, supplied an enormous quantity of texts through which changes in words’ meaning could be traced Semantic Change Because of this history, Indo-European languages have had an overwhelming importance in the study of semantic change This tradition has meant that studies of semantic change have traditionally relied on IndoEuropean evidence much more than have other domains of linguistics Semantic Change In contrast, we are largely in the dark about long-term sense developments in the languages of oral societies, which lack the written evidence on which historical study needs to be based Semantic Change Unlike sound change, which seems to be governed by regular laws of great generality which are open to scientific study, meaning change has often struck investigators as chaotic and particularistic Semantic Change Since changes in words’ meaning are often determined by socio-cultural factors, much meaning change is not even linguistically motivated For instance, since the advent of modern air transport, the verb fly can refer to ‘travelling as a passenger in an airplane’ Semantic Change This is a meaning that was obviously unavailable before the twentieth century But it does not necessarily correspond to any change in the sense of fly itself: this is still arguably ‘travel through the air’ Semantic Change What has caused the change of meaning is arguably not anything to do with language, but simply a change in the word’s denotation An important characteristic of semantic change is that it crucially involves polysemy Semantic Change A word does not suddenly change from meaning A to meaning B in a single move Instead, the change happens via an intermediate stage in which the word has both A and B among its meanings Semantic Change The Traditional Categories Early studies of semantic change (going back the 1890’s) did little more than set up broad categories of change, described with very general, and often vague, labels like ‘weakening,’ ‘strengthening,’ and so on Semantic Change First, we will consider four of these traditional categories of semantic change: Narrowing (Specialization/Reduction) Broadening (Generalization/Extension) Amelioration (Elevation) Pejoration (Degradation) Semantic Change One common type of change is Narrowing in which a word narrows its range of reference: For example: English liquor used to refer to liquid of any kind: the reference to alcohol was a subsequent narrowing Semantic Change English pavement originally referred to any paved surface, but narrowed (in British English) to simply cover the footpath on the edge of a street (which we, of course, call the sidewalk) This happens in other languages as well, of course Semantic Change The proto-Romanian word for ointment, unctu, narrowed in Romanian so as only to refer to a single ‘ointment,’ butter (as well as undergoing some phonological changes to become unt) Semantic Narrowing is less common, historically, than extensions, though it is still found fairly frequently Some other examples: OE hund ‘hound’ originally all dogs, now to a particular type of dog ME girl originally referred to young people of any gender Semantic Change The opposite tendency is Broadening in which a word’s meaning changes to encompass a wider class of referents Zealot originally referred to members of a Jewish resistance movement against the occupying Romans in the first century AD Semantic Change Its contemporary meaning ‘fanatical enthusiast’ is a later broadening French panier ‘basket’ originally meant just a bread-basket; it was subsequently broadened to baskets of any kind The Latin noun passer means ‘sparrow’ Semantic Change But in a number of Romance languages it has generalized to the meaning of ‘bird’: this is the case, for example, with Spanish pájaro and Romanian pasăre The most common verb for ‘work’ in Romance languages, like French travailler and Spanish trabajar, is a result of a broadening Semantic Change From the Latin ‘tripaliare’ – ‘torture with a tripalium,’ a three-spiked torture instrument The German adverb sehr ‘very’ originally meant ‘cruelly’ or ‘painfully’ (a trace of this meaning survives in the verb versehren ‘injure’ or ‘hurt’ Semantic Change The shift to ‘very’ is an example of an extreme broadening that has lost almost all connection with the original sense Sound strange? A similar change is found in many English intensifier terms, like terribly and awfully Semantic Change Broadenings are frequently the result of generalizing from the specific case to the broader class of which the specific case is a member. An example from Old English is the following: Originally the word ‘dog’, pronounced OE [docga], referred to a specific breed of dog. The same is true of the word ‘bird.’ Semantic Change Broadening seems particularly common with proper names, such as: -Jello -Kleenex -Xerox -Coke Semantic Change The two other traditional categories in the analysis of meaning change, Pejoration and Amelioration, refer to changes in words’ evaluative force In Pejoration, a word takes on a derogatory meaning Semantic Change This is frequently seen with words for animals, which can be used to refer to people negatively or insultingly, as when someone is called a parasite, pig, sow, and so on Another example of pejoration is the adjective silly This originally meant ‘blessed, happy, fortunate’ Semantic Change Its contemporary meaning ‘foolish’ is a later development – and one which, this time, has entirely displace the original sense Similarly, boor’s original meaning was ‘farmer’ ‘crude person’ was a later pejoration Semantic Change Accident originally meant simply ‘chance event,’ but took on the meaning ‘unfavorable chance event’ Amelioration is the opposite process, in which a word’s meaning changes to become more positively valued The normalization of previously proscribed taboo words is a good example (like ass) Semantic Change One example of amelioration is the word is provided by the English word nice The earliest meaning of this adjective, found in Middle English, is ‘simple, foolish, silly, ignorant’ The basic modern sense, ‘agreeable, pleasant, satisfactory, attractive’ is not attested until the 18th century Semantic Change It is interesting to note that semantic changes in one word of a language are often accompanied by (or result in) semantic changes in another word For example: as hund became more specific in meaning, dog became more general, and viceversa In this way, the semantic system as a whole seemed to remain in balance Semantic Change Unfortunately, these four categories on their own are not quite adequate to describe the complexities and diversity of the types of meaning change encountered in the history of languages How do we explain, for instance, the shift of Latin ver ‘spring’ to the meaning ‘summer’ in many Romance languages? Semantic Change This seems to fit none of the four categories so far mentioned The same could be said for the development from Latin sensus ‘sensation, consciousness, sense’ to the meaning ‘brains’ in Spanish seso Semantic Change A solution to this sort of problem comes from recognizing narrowing and broadening are just two types of metonymic change Metonymy is the process of sense development in which a word shifts to a contiguous meaning ‘Contiguous’ has a number of different meanings Semantic Change But the essential idea is that two senses are contiguous if their referents are actually next to each other, either spatially or temporally Or if the senses underlying the words are closely related conceptually Semantic Change The Spanish ‘consciousness’ > ‘brains’ shift exemplifies conceptually contiguity (brains and consciousness have a close conceptual association) while the ‘spring’ > ‘summer’ shift exemplifies both temporal and conceptual contiguity: summer is next to spring in time, and also a closely related notion conceptually Semantic Change Some instances of pejoration and amelioration can also be considered metonymic The shift of boor from ‘farmer’ to ‘crude person’ could be considered to be based on the close association of these two notions (at least historically) Semantic Change Metonymy is a powerful category It can describe many types of changes which can’t otherwise be accommodated The English noun bead originally meant ‘prayer’ in Old English Its present meaning can be explained through the widespread use of the Catholic Rosary Semantic Change This association established a conceptual link between the notions ‘prayer’ and ‘bead,’ explaining the metonymic transfer of bead to the latter meaning in the Middle English period This is neither narrowing/broadening nor pejoration/amelioration, so a new category is clearly needed Semantic Change Metonymic changes are common A particularly colorful one underlies the word pupil, which in English refers both to a student and to the opening in the eye through which light passes This puzzling polysemy goes back to Latin, where pupilla means both ‘small girl, doll’ and ‘student’ Semantic Change Our eyes have ‘pupils’ because of the small doll-like image that can be observed there: spatial contiguity, in other words, underlies the shift Another example of a metonymic meaning shift is the Romanian word bărbat ‘husband,’ which derives from the Latin barbatus ‘bearded’ Semantic Change If husbands often have beards, the ideas will be conceptually associated Metonymy was a notion adopted into linguistics from rhetoric, the traditional study of figurative, literary and persuasive language Another originally rhetorical concept with linguistic application is metaphor Semantic Change Metaphors are based not on contiguity, but similarity or analogy English germ is a good example of a metaphor-based meaning change The earlier meaning of this word was ‘seed,’ as in this example sentence from 1802: Semantic Change ‘The germ grows up in the spring, upon a fruit stalk, accompanied with leaves’ The word’s application to the microscopic ‘seeds’ of disease is a metaphorical transfer: ailments are likened to plants, giving them ‘seeds’ from which they develop Semantic Change The Old French word for ‘head,’ test, is another example of metaphorical development Originally, test meant ‘pot’ or ‘piece of broken pot’ The semantic extension to ‘head’ is said to be the result of a metaphor current among soldiers, in which battle was described as ‘smashing pots’ Semantic Change Exactly the same metaphor explains the sense development of German kopf ‘head,’ which used to mean ‘cup’ The use of monkey, pig, sow in pejorative reference to people can also be seen as the result of metaphor based on perceived similarity with the animals concerned Semantic Change The centrality of metaphor and metonymy in semantic change is due to the fact that they jointly exhaust the possibilities of innovative word use and thus subsume all the other descriptive categories The argument, according to Nerlich and Clarke (1992), is: Semantics Change If you want to express yourself innovatively and be understood, then there are only two ways of going about that: using words for the near neighbors of the things you mean (metonymy) or using words for the look-alikes of what you mean (metaphor) Semantic Change The descriptive approach to semantic change described thus far is far from ideal The categories are vague and purely taxonomic, and offer no explanatory insight into the conditions under which meaning change happens Semantics Change They are also highly informal, and lack clear criteria for their application This is particularly true for amelioration and pejoration Whether a meaning change is in a positive or negative direction will often depend on little more than one’s subjective judgment Semantic Change For example, the change of English knight from the meaning ‘boy, servant’ to the meaning referring to the aristocrat is often described as amelioration But this is only the case if the latter meaning is evaluatively superior to the former, a judgment that not everyone would share Semantic Change Another problem with the traditional categories is that they are also either too powerful or not powerful enough In the case of narrowing/broadening and amelioration/pejoration, there aer many meaning changes which do not seem to fit Semantic Change In the case of metonymy/metaphor, the categories seem to be able to explain any change, since we can always find some connection of similarity or contiguity between two meanings to justify their treatment as one or the other category (think six degrees of separation for Kevin Bacon) Semantic Change The traditional analysis of semantic change seems worlds away from the kinds of precise explanations that are possible in the study of sound change More recent work attempts to go beyond the mere description of changes, and search for causal explanations Semantic Change There is much disagreement For some scholars, the categories of metonymy and metaphor themselves are cognitively real and hence explanatory: cognitive linguists take metonymy and metaphor as basic cognitive operations which are at work throughout language Semantic Change From this point of view, it is not surprising that metaphor and metonymy are prominent in meaning change, since they are also the principles behind much synchronic semantics Semantic Change For someone committed to understanding language in terms of metaphor and metonymy, the contrast between explaining semantic change and just describing or classifying it collapses The shift from germ ‘seed’ to germ ‘microbe’ is explained, not just classified Semantic Change Simply by virtue of being identified as a metaphor For others, however, this type of explanation is not satisfactory Much modern work on semantic change stresses the role of the conventionalization of implicature as a source of semantic change Semantic Change Consider the pejoration of English accident The original sense of ‘chance event’ would often have been used in discourse circumstances where the unfavorable nature of the event was strongly implied, as in this sentence from 1702: Semantic Change ‘The wisest councils may be discomposed by the smallest accidents’ The more neutral description ‘chance event’ would seem perfectly appropriate to the sense of accident present here Semantic Change The context, however, strongly implies that the chance event is unfortunate or regrettable, since it ‘discomposes the wisest councils’ According to the conventionalization of implicature theory of semantic change, accident would have become increasingly associated with contexts like that above Semantic Change And the implication that the event was unfavorable or regrettable would have been progressively strengthened On encountering accident, speakers would increasingly associate it with contexts like that above, and assume that the event was an unfavorable one Semantic Change With time, this process of strengthening would change the status of reading ‘unfortunate/unfavorable chance event’ from an implication to part of the word’s literal meaning Semantic Change The pejoration of accident is thus the result of the conventionalization of an implicature This explanation does not deny that there is a relation of ‘contiguity’ between the notions ‘chance event’ and ‘unfavorable chance event’ Semantic Change It is also not incompatible with an explanation based on metonymy But it goes further, by showing that the actual discourse mechanisms which allow the contiguity to become relevant Such explanations, then, put pragmatic considerations at the heart of understanding change Semantic Change To understand why meaning changes, this perspective argues, we should not be thinking in terms of broad cognitive operations like metaphor and metonymy, but should look instead at how inferences generated in discourse become part of lexicalized word meaning Summary/Minute Paper: