Extreme Value Analysis EVA

advertisement

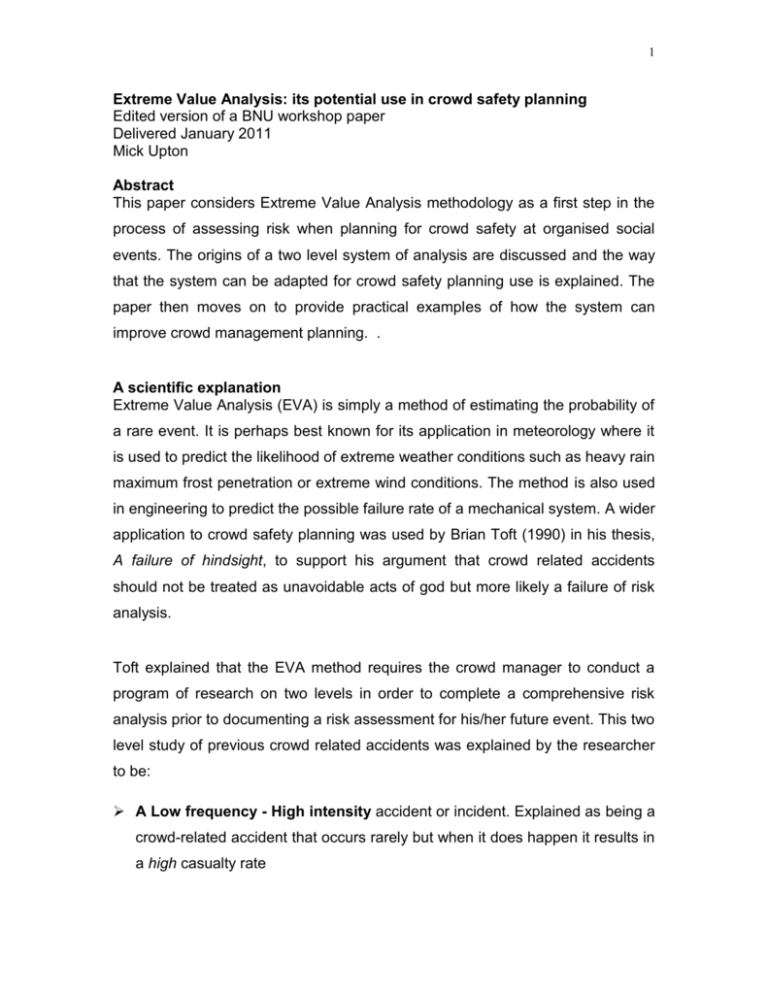

1 Extreme Value Analysis: its potential use in crowd safety planning Edited version of a BNU workshop paper Delivered January 2011 Mick Upton Abstract This paper considers Extreme Value Analysis methodology as a first step in the process of assessing risk when planning for crowd safety at organised social events. The origins of a two level system of analysis are discussed and the way that the system can be adapted for crowd safety planning use is explained. The paper then moves on to provide practical examples of how the system can improve crowd management planning. . A scientific explanation Extreme Value Analysis (EVA) is simply a method of estimating the probability of a rare event. It is perhaps best known for its application in meteorology where it is used to predict the likelihood of extreme weather conditions such as heavy rain maximum frost penetration or extreme wind conditions. The method is also used in engineering to predict the possible failure rate of a mechanical system. A wider application to crowd safety planning was used by Brian Toft (1990) in his thesis, A failure of hindsight, to support his argument that crowd related accidents should not be treated as unavoidable acts of god but more likely a failure of risk analysis. Toft explained that the EVA method requires the crowd manager to conduct a program of research on two levels in order to complete a comprehensive risk analysis prior to documenting a risk assessment for his/her future event. This two level study of previous crowd related accidents was explained by the researcher to be: A Low frequency - High intensity accident or incident. Explained as being a crowd-related accident that occurs rarely but when it does happen it results in a high casualty rate 2 A High frequency - Low intensity accident or incident. Explained as being a crowd-related incident that might occur at regular intervals but result in a low casualty rate. In support of his thesis argument Toft provided two examples of fires at entertainment venues that were the cause of loss of life. The two fires occurred at the Iroquois Theatre, Chicago, 1903, and the Coconut Grove Nightclub, Boston in 1942. Both fires appear to have occurred in remarkably similar circumstances. Toft explains that in both cases the decorative fabric of the interiors was highly inflammable, exits were locked or had not been provided, both venues were overcrowded and neither establishment had trained their staff to deal with an emergency such as fire. It would be a dangerous assumption to dismiss Toft`s comparative study as being simply two fires that occurred coincidentally in similar circumstances almost forty years apart. He simply chose one example to illustrate a low frequency – high intensity incident. The rationale applied by Toft was that had the operators of the Coconut Grove nightclub researched the cause and effect of fires at entertainment venues they would have found the basis for improved crowd safety planning at the Coconut Grove nightclub years later. The time period between the two fires is irrelevant. For as the philosopher George Santayana (1905) famously warned, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”. Sadly it would appear from the evidence available today that the contributory factors to a high loss of life in the two fires cited by Toft still appear to be contributing factors to a high loss of life in fires at clubs and discos today. 3 Fires at indoor venues are obviously not the only cause of loss of life at organised crowd gatherings. There have been fatal accidents due to high density crush situations, cultural behavior and falls at crowd gatherings that range from concerts to religious meetings and retail outlets (shops). Wherever crowds are encouraged to form the possibility of an accident exists and it might be argued that the larger the crowd the greater the potential for an accident simply because more people increase the likelihood of an incident. This does not imply that all organized crowd gatherings are dangerous, rather that it is essential to plan for the needs of a crowd. The event organiser has a mandatory obligation to ensure maximum safety standards for the public attending their event and common practice in the UK is to delegate responsibility for crowd safety to a crowd management consultant. The delegation of responsibility to a consultant does not mean that the event organiser is absolved from all responsibility however because their choice of consultant would be a prime consideration at an inquiry into an accident. On that basis it is reasoned here that it is good practice for all individuals and organisations involved with crowd safety planning to have an understanding of the two level approach to risk analysis that the EVA method recommends in order to make an informed choice of consultant. Low frequency – High intensity An obvious start point for a better understanding of the EVA method is low frequency – high intensity. Simply because a high intensity indicates a fatal accident and therefore information regarding the possible cause and effect are likely to be available from press accounts, online reports and public inquiry reports. Great care needs to be taken when considering statements made by members of the crowd however. Regardless of how tall a person is, when they are standing within a dense crowd they cannot see what is taking place even when an incident 4 is unfolding close by. People in a crowd situation tend to make uninformed comments to the media. This is a particular problem with accidents at concert events where fans rarely consider the artiste on stage to have contributed to the cause of an accident, even if the artiste has encouraged reckless or irresponsible behaviour. Fans are far more likely to accuse a front of stage pit team of failure to act or the promoter for failing to take action to stop the show. The crowd manager therefore has to critically appraise the information obtained on crowdrelated accidents and a reasonably accurate cause and effect pattern documented for possible reference later when planning an event. An example of the value of data collection and storage can be seen if we turn the clock back to 1989. Imagine that we are responsible for planning for crowd safety at an important FA Cup football match at Hillsborough between Nottingham Forest and Liverpool. Online research would not be easy in 1989 but crowd safety issues have been documented since the first FA Cup Final at Wembley Stadium in 1926 when literally thousands of people without tickets climbed over the stadium walls. Information is available if we look hard enough. If we had studied the documented history of accidents and incidents at football grounds we would easily have discovered that thirty-three people died and an estimated five hundred others were injured during a FA Cup match between Bolton Wanderers and Stoke City on the 9th March 1946 at Burnden Park, Bolton. The Molwyne Hughes Report into the Burnden Park disaster indicates that possible contributing factors to the loss of life in the accident were: Late arrival of a large crowd Game started while a large number of fans were still outside trying to get into the ground Failure of crowd control outside of the ground Ingress system at one section of the ground unable to cope with a crowd rush This resulted in high crowd density in one section of the ground A perimeter fence prevented people in distress form moving onto the pitch The police assumed that they were dealing with a public order problem Venue staff were untrained volunteers 5 A perimeter fence then collapsed causing injury A police officer had to go onto the pitch to ask the referee to stop the game once it was realised that there was a serious safety problem Crowd members in other parts of the ground then assumed that the police had stopped the game because of disorder by a section of the crowd Now fast forward forty-three years to our match at Hillsborough and our pre match planning has focused on the need to maintain public order because soccer hooliganism has been an on going problem for years now. On mach day our crowd segregation plan is working well and the match starts on time. Then a large crowd arrives late to one section of the ground where the ingress system cannot cope. The police cannot control the crowd outside and hundreds of people rush into a pen that is already full. We have not trained our stewards to deal with the situation and the police immediately assume that they are dealing with a public order problem. Sadly ninety-six people die and hundreds more are injured as a result of being trapped behind a pitch perimeter fence. Given the fact that our 1989 disaster has occurred in remarkably similar circumstances to that which occurred at Burnden Park forty-three years earlier, what does that say about our approach to match day planning? High frequency – Low intensity Turning to high frequency – low intensity assessment, possibly the best example can be seen regularly at pop and rock concerts where many hysterical or distressed members of an audience are extracted from the crowd at the front of the stage and taken to first aid. Experienced practitioners will know that it is often the case that literally hundreds of young people will be treated on site and then allowed back into the audience to continue watching the show. Responsible concert promoters put front of stage barrier systems into place to deal with these situations and they continually upgrade these systems to cope with new cultural attitudes. Consequently the press rarely reports such incidents. 6 This does not imply that information cannot be found; rather that it takes more effort. Take for example a casual BBC TV News (2008) report that a crowd of 2000 mainly young women turned up to see a free concert at Fairfields Hall, Croydon, on the 30th October 2008 by the UK group JLS. The venue only holds 1500 people and not surprisingly there were reports of crowd hysteria from young women that could not get in. This report does not however seem to have flagged up a warning for the management of a shopping centre in Manchester because in 2009 the Daily Mail (2009) reported that “Thousands of screaming fans turned out to see the group JLS as they turned on the Christmas lights at the Trafford Centre”. The paper further stated that “The gates were firmly closed by 4pm, as the giant shopping centre was almost overwhelmed”. On the 14th November 2009 local authority organisers of a free concert by JLS in Birmingham were surprised when a larger than expected crowd of young females turned up to see a free concert. The venue was full, but people appear to have broken through a barrier system and the concert was cancelled for public safety reasons. In each of the incidents cited here the event was free, more people arrived than the organisers expected, the crowd profile was predominantly young female and crowd hysteria was a key factor. Fortunately there were no serious injuries recorded and therefore might be regarded by safety planners as being three `near miss` incidents. It also raises the possibility that at least two previous warnings were overlooked by the organisers of the Birmingham event. Similarly, the organisers of an appearance by the boy band One Direction in Wolverhampton on the 8th December 2010 seem to have been taken by surprise by the actions of the crowd attending the open air event. A press report claimed that 35 young female fans required medical treatment at the free promotional concert (Daily Mail 2010). It appears that fans turned up very early to the free event, possibly not having eaten and waited for a long period in temperatures below zero. This scenario is remarkably similar to that of the 1979 Cincinnati disaster referred to at the beginning of this paper that cost the lives of eleven young rock fans. 7 It is not always as easy to predict a potential incident, but the cause and effect of so-called near miss incidents that occur are crucial to a risk analysis process. For as Toft (1990b) quite rightly argued, “near misses should not be shrugged off but instead be treated as fortunately benign experiences, since if the same events were to repeat themselves in less forgiving circumstances then disaster might ensue”. Cross organisational learning Where there is a lack of credible data on accidents at a particular category of event the researcher must extend their area of search beyond their particular event or venue in order to take into account the importance of what is often referred today as environmental psychology. In his discussion on the concept of isomorphism (the similarity of organisms of different ancestry), Beishon (1980) argued that: `It did not matter whether a particular system was biological, sociological or mechanical in origin, it could display the same (or essentially similar) properties, if it was in fact the same basic kind of system`. Consequently, even when two systems might appear to be completely different, if they posses the same or similar component parts or procedures then they will both be open to a common mode of failure. It can be assumed from this that a queue system requires the same level of attention regardless of what people are queuing for. For if seemingly different systems can display the same or similar properties it follows that they can also be subject to the same failure modes. Toft drew on this hypothesis to argue that the similar features of accidents were that any failure that occurs in one system would have a propensity to recur in another `like` system for similar reasons. Concert planners for example can learn lessons from queue systems failures at special offer sales at retail outlets. The common factor is that pre event marketing shapes the psychology of the crowd prior to their arrival. At concert events crowds will arrive early regardless of the fact that they have a ticket 8 because they are determined to get as close to the front of stage as possible while at sales people arrive early to obtain a bargain. In this scenario specific attention needs to be paid to queue and ingress management, staff training and communications Some retail managers appear to have been slow to take advantage of inter organisational and cross organisational learning. Reports indicate that there has been a number of `near miss` incidents at retail outlets. Stores that have failed to learn include: IKEA, (one serious incident in London and a fatal incident in Jeddah); Primark (two serious incidents in London); Gucci’s flagship store in Knightsbridge, West London (public disorder during queuing) and Curry’s store Birmingham (one serious incident). In each case it was reported that thousands more people turned up than was expected and staff were not able to control queuing and ingress and the police were called to restore public order. Far more serious was a queue failure at a Wal-Mart store in America where one person died. From TV and press reports on these incidents it would appear that store managers and staff in all cases did not have the knowledge and training to understand crowd behaviour therefore they failed to understand the powerful forces that can be generated by crowds in spite of the fact that there were numerous warnings. Conclusions At the key stage of event risk analysis there is much to be gained by conducting a wide-ranging program of research into crowd related accidents and incidents. It is a fatal mistake to restrict the search to your own particular event or venue type. For example, football Safety Officers should not focus solely on football incidents or sports grounds, equally the concert promoter should not ignore incidents that appear to have nothing to do with concert events. Crowd safety risk analysis needs to focus on the possible environmental psychology of crowds during four key phases of; 9 Crowd arrival and queuing Ingress and/or processing Attendance Egress to include possible evacuation The overall aim throughout each of these phases is to control crowd density. The nature of the event or venue type is irrelevant as even the best architecturally designed venues can experience an accident if arrangements are not made to take into account the attitude of an attending crowd. Ref used BBC TV 2008: BBC Television News report: Hysteria at Croydon Theatre 9th December 2008 Beishon 1980: The concept of isomorphism: quoted by Toft B. 1990 in A failure of hindsight: Published thesis Daily Mail 2009: Its JLS mania as thousands of fans turn out to see X Factor group turn on lights: 5th November 2009 Daily Mail 2010: Girls go wild for One Direction: Page 3 Thursday December 9th 2010 Santayana G.1905: The Life of Reason, Volume 1: BiblioBazaar 2009 Toft B.1990: Thesis: A failure of hindsight: University of Exeter 1990