How Do Historians Evaluate the Administration of Lyndon Johnson

advertisement

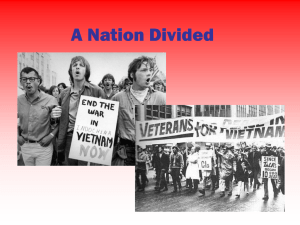

Presidency: How Do Historians Evaluate the Administration of Lyndon Johnson? By Robert Dallek Mr. Dallek is the author of Flawed Giant: Lyndon Johnson and His Times, 19611973, which is available in paperback. What makes a great president? Washington, Lincoln, and Franklin Roosevelt are almost universal choices among historians as setting the standard. Each was a practical visionary with an uncommon hold on the imagination of their countrymen during their own times and as admired historical figures. Where does Lyndon B. Johnson fit in the pantheon of great, near great, average, below average and failed presidents? LBJ stands with a handful of important presidents who had exceptional accomplishments and some terrible failures. In the twentieth century, the predecessor who most seems to parallel LBJ is Woodrow Wilson. A great leader in domestic affairs, Wilson fell well short of his stated goals in foreign policy. His hopes for nonintervention in the Western Hemisphere and World War I as well as his dreams of lasting peace at the end of the fighting in 1918 were never realized. SIGNALS OF SUCCESS Johnson suffered a similar fate in the White House. As the successor to a martyred John F. Kennedy in 1963, Johnson seized upon the national mood of regard for the fallen president to win passage of his major unrealized legislative initiatives - an $11 billion tax cut, the 1964 civil rights bill, and subsequently, in 1965, the Medicare/Medicaid and federal aid to education laws. Johnson was not content to simply embrace JFK's proposals. He successfully took up the cudgels for the voting rights, open housing, immigration reform, environmental protections, consumer safety bills, cabinet departments of transportation and housing and urban development, cultural reforms like the National Endowments for the Arts and Humanities and the Freedom of Information Act. The War on Poverty also became part of his presidential legacy. Head Start, food stamps, elimination of urban slums, public housing, expanded social security, legal services and expanded welfare to needy citizens added up to an assault on poverty that reduced the percentage of Americans living in penury from roughly 23 percent to 12 percent. Although a number of Johnson's initiatives fell short of what he hoped they might accomplish, his domestic reforms added up to a record of liberal alterations that rivaled FDR's New Deal. Moreover, Johnson's civil rights actions permanently transformed the South. They destroyed the long standing de jure and de facto traditions of racial segregation and opened the way to equal treatment of African Americans in every region of the country. Johnson himself believed that this was his greatest achievement. He was right. And his claim on presidential greatness here is served by the reality, which he glimpsed at the time, that his support of black equality would allow the Republican Party to eclipse his Democratic Party in his native Texas and across the rest of the South. FILLING A HOLE IN THE OCEAN Johnson's courage and wisdom in backing a civil rights revolution did not replicate itself in overseas affairs, especially Vietnam. To be sure, Johnson inherited the conflict in southeast Asia from the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations, but he made firm commitments to the war that turned the conflict into a much larger struggle that cost the United States tens of thousands of lives and billions of dollars and shattered LBJ's hold on the country. Convinced it was in the country's national interest to combat Communist aggression in Vietnam, believing that a failure to fight a limited war would lead to a larger one with Russia and China, and fearful that losing Vietnam would touch off a right-wing, McCarthyite reaction in the United States, Johnson sent over 500,000 U.S. troops to fight the war. His assumption that a combination of bombing, ground forces and aid to the Saigon government would assure the independence of South Vietnam proved to be false. Despite repeated assertions that American was winning in Vietnam, Johnson could not convince Americans we were achieving our goals, especially after Tet, the North Vietnamese-Viet Cong offensive early in 1968 that seemed to give the lie to Johnson's assertions about the fighting. In March 1968, despite all his domestic gains, Johnson faced an America so divided by the conflict in Vietnam that he had to announce his withdrawal from that year's presidential campaign. The national reaction against his policy allowed Richard Nixon to best Hubert Humphrey for the presidency and opened the way to the painful events of the 1970s, particularly Nixon's Watergate crisis and the only resignation of a president in American history. A MIXED BAG Johnson's historical reputation has recently been on the upswing as recriminations over Vietnam fade and Americans recall that his Great Society and War on Poverty marked out notable advances in the country's domestic life for which he deserves substantial credit. Lyndon Johnson will always be the object of historical debate. But unlike so many of our other presidents, he will not become a nameless, faceless character. He will be remembered as a larger-than-life figure with great accomplishments and great failings.