Proposal - CEPAM

advertisement

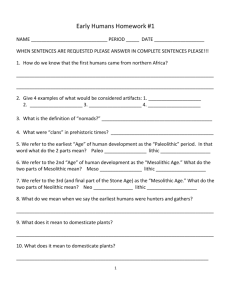

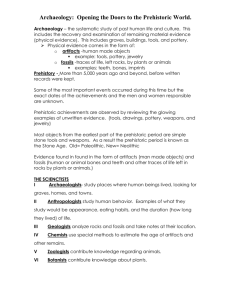

PROPOSED SESSION FOR THE SAA 73RD ANNUAL MEETING IN VANCOUVER, CANADA – March 26 - March 30, 2008 SCARCITY’S APPRENTICE Raw Material Availability and the Transmission of Skill in Prehistoric Lithic Technology Lotte Eigeland (Museum of Cultural History, Oslo, Norway) and Farina Sternke (University of Glasgow, United Kingdom) The study of skill in lithic technology has contributed greatly to prehistoric studies since the 1980s (e.g. Pelegrin 1985; Pigeot 1987, 1990; Bodu et al. 1990; Fischer 1990, Roux et al. 1995; Apel and Knutsson 2006). To date, these studies have been carried out for the most part in Central Europe (France) and Southern Scandinavia (Denmark). The skill perspective has lead to a greater understanding of social aspects in a period that previously had been dominated by economically and ecologically oriented interpretations. Nowadays, archaeologists are asking new questions related to the social organisation of technology in prehistoric communities such as: Who acquired which skill? How were these skills transmitted and at what age? How long did an apprenticeship last? The answers to these important questions will ultimately further our insights into the transmission of knowledge and traditions in prehistoric societies. Skill transmission in lithic technology has so far been explored through an investigation of masterpupil relationships at high-resolution archaeological sites (e.g. Pigeot 1987, 1990; Fischer 1990; Högberg 1999; Grimm 2000). At other sites, the teaching process appears to be more opportunistic and self-taught (e.g. Sternke 2005; Eigeland 2007). Both of these interpretations are based on information discovered at sites in particularly flint-rich regions. In flint scarce regions, however, very little research on skill has been carried out. In this respect, the following questions are worth exploring in the context of a dedicated session at the meeting of SAA in 2008: How did the transmission of skill take place, when there was little flint available? Did the process of skill acquisition and teaching differ in flint-scarce regions? Are differences in technological traditions and the occurrence of local innovations a direct result of a modification of skill transmission due to raw material availability? 1 Further, we believe that a comparison of the diversity of skill acquisition and its organisation between different regions, particularly those with distinct raw material distribution patterns, will provide us with new insights into the social and technological organisation of prehistoric societies. For this proposed session, we would like to invite contributions relating to skill development and transmission in the lithic technologies of all prehistoric/archaic periods. While we are not excluding flint-rich regions, we would like to encourage contributions from as many diverse regions as possible. Bibliography (selection): Apel, J. and K. Knutsson (eds), 2006. Skilled Production and Social Reproduction. Aspects of Traditional Stone-Tool Technologies. Uppsala: Uppsala University. Bodu, P., Karlin, C. and S. Ploux, 1990. Who’s Who? The Magdalenian flintknappers of Pincevent, France. In E. Cziesla, S. Eickhoff, N. Arts and D. Winter (eds.) The Big Puzzle. International Symposium on Refitting Stone Artefacts. Bonn: Holos Verlag, Studies in Modern Archaeology 1, 143163. Eigeland, L. 2007. Pride and Prejudice. Who should care about non-flint raw material procurement in Mesolithic South-East Norway? Lithic Technology 32 (1). Fischer, A., 1990. On being a pupil of a flintknapper of 11,000 years ago. A preliminary analysis of settlement organization and flint technology based on conjoined flint artefacts from Trollesgave site. In E. Cziesla, S. Eickhoff, N. Arts and D. Winter (eds) The Big Puzzle. International Symposium on Refitting Stone Artefacts. Bonn: Holos Verlag., Studies in Modern Archaeology 1, 447-464. Grimm, L., 2000. Apprentice flintknapping: relating material culture and social practice in the Upper Palaeolithic. In J. Sofaer Derevenski (ed.) Children and Material Culture. London and New York: Routledge, 53-71. Högberg, A., 1999. Child and adult at a knapping area. Acta Archaeologica 70, 79-106. Pelegrin, J., 1985. Reflexion sur le comportement technique. In: M. Otte (ed) La signification culturelle des industries lithiques. Oxford: BAR International Series No. 239, 72-82. Pigeot, N., 1987. Magdaléniens d’Etiolles: économie de debitage et organisation sociale. CNRS, Paris. Pigeot, N., 1990. Technical and social actors. flintknapping specialists and apprenticeship at Magdalenian Etiolles. Archaeological Review from Cambridge 9 (1), 126-141. Roux, V., Bril, B. and G. Dietrich, 1995. Skills and learning difficulties involved in stone knapping: the case of stone-bead knapping in Khambhat, India. World Archaeology 27(1), 63-87. Shelley, P. 1990. Variation in Lithic Assemblages: An Experiment. Journal of Field Archaeology 17 (2), 187-193. Sternke, F. 2005. All are not Hunters that Knap the Stone - A Search for a Woman's Touch in Mesolithic Stone Tool Production. In N. Milner and P. Woodman (eds) Mesolithic studies at the beginning of the 21st Century. Oxford: Oxbow, 144-163. 2 Abstract Submission Guidelines Final Submission deadline: 8th September 2007. We would like to ask participants to provide their full names, affiliation, a short abstract and title. Contributions in both, English and French are welcome. The word limit for the abstract is 300 words plus five keywords. There are no limitations on lithic raw material types and archaeological periods. The presentations will be about 15 mins long in accordance with SAA guidelines. The proceedings of this session will be prepared for publication, possibly in the form of a Special Issue of Lithic Technology. Abstracts should be sent via email to Lotte Eigeland (lotte@superheros.as) or Farina Sternke (F.Sternke@ucc.ie) . 3