Antidepressant Use Discussion Paper

advertisement

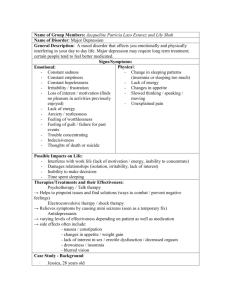

Increasing use of antidepressants in New Zealand Mental Health Foundation of New Zealand Discussion paper January 2012 Introduction There is a widely held belief amongst the public, media and government agencies that depression is a modern-day epidemic (see Mental Health Foundation, 2012). However, there has been a counterargument that it is in fact antidepression prescription that is reaching epidemic proportions (Summerfield 2006). Currently, antidepressants (prescriptions to treat depression) are widely viewed internationally as the preferred ‘first line’ response to depression, with most people seeking treatment for depression being treated with antidepressants in the first instance (Moncrieff & Kirsch, 2005). Consequently, in New Zealand increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of the use of antidepressants is often presented as an important strategy for addressing the burden of mental health problems and preventing suicide, and so this has been an on-going focus of government, pharmaceutical companies and health consumers (Ministry of Health, 2007). There is also a trend of increased prescribing of antidepressants in New Zealand, as internationally. But does increased antidepressant prescription equate to improved management of depression? A good deal of clinical literature continues to appear to assume that antidepressants are the most appropriate (and effective) medical response to depression; however, this is contested territory. There is on-going clinical over whether increased prescribing is a public health good (for example signifying increased public awareness of depression, more efficient diagnosis of depression in the community and better treatment access; e.g. Exeter, Robinson, & Wheeler, 2009) or whether current practice amounts to ‘over- prescription’, based on an inappropriate reliance on pharmacological solutions to depression. In spite of the primacy of pharmacological treatment approaches, definitive knowledge of the biochemical processes involved in depression continues to elude researchers (also see Mental Health 1 Foundation, 2012); similarly, there continues to be a lack of clinical consensus on the actual pharmacologic mode of action of antidepressants. This paper considers current trends in the use of antidepressants as the predominant treatment response to depression, on-going clinical debates around the efficacy and safety of antidepressants, and the evidence for a gradual shift towards non-pharmacological responses to depression in public health. Antidepressant prescription trends Antidepressants, in particular selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRI’s), are now among the most widely prescribed type of medication globally (Murphy, Kremer, Rodrigues, & Schatzberg, 2003). International research indicates a dramatically increased use of antidepressants since the introduction of third-generation (SSRI) drugs in the early 1990s, with prescription rates continuing to rise exponentially (Moncrieff, 2001; Gunnell & Ashby, 2004; Moore et al., 2009). For example, research shows that antidepressant prescribing has more than doubled in the last two decades in the United Kingdom and other Western countries, with evidence of long-term trends of increasing prescribing since the mid-1970s (Gunnell & Ashby, 2004; Moore et al., 2009), and New Zealand data similarly reflect a trend of increasing prescription rates (Exeter et al., 2009). As Dijkstra & Jaspers (2008, p. 149) noted, ‘All these data suggest that the increase in the use of antidepressants on a global level is still in full progress’. Twenty antidepressant drugs are currently approved for use in New Zealand. The most frequently prescribed is Paroxetine (‘Aropax’), followed by Fluoxetine (‘Prozac’) (Reith, Fountain, Tilyard, & McDowell, 2003). Ministry of Health data show that between 1997 and 2005 the number of prescriptions for a course of antidepressants doubled (from 1.1 to 2.1 million). This increase was largely in the prescription of SSRIs, rather than Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), which showed only a small increase during this period. Similarly, the most recently available PHARMAC (personal communication, 2011) data show a clear trend of increased prescription between 2006 and 2010 for all age groups other than under 13 years. These increases are especially significant for the 18–24 age group (from 51,000 to 69,000), the 25–44 age group (from 246,000 to 354,000) and the 45–64 age group (from 356,000 to 498,000). Recent data indicate that around 10% of the New Zealand adult population is currently being prescribed an antidepressant (Exeter et al., 2009; PHARMAC, personal communication, 2011). There are several clear trends in the available New Zealand antidepressant prescription data. Firstly, there are obvious regional differences in prescription rates. Most notably, Canterbury District Health Board has the highest rate of antidepressant prescription (any type) nationally, and double the rate of SSRI prescription compared with the lowest regional rates across the Auckland District Health Boards (Ministry of Health, 2007). Similarly, more recent PHARMAC figures show that in 2010, Canterbury District Health Board (population 491,000) recorded 197,000 prescriptions, compared with 85,000 in Counties Manukau (population 468,000) and 132,000 in Waitemata (population 516,000). There are also significant differences in prescription rates between ethnic groups, with considerably higher rates for New Zealand European than for both Māori and Pasifika groups. This is consistent with previous research, which has found that Māori are less likely than non-Māori to be treated with antidepressants (Arroll, Goodyear-Smith, & Lloyd, 2002) and that there is lower access to mental 2 health treatment more generally among Māori and Pasifika peoples (Baxter, Kokaua, Wells, McGee, & Browne, 2006). In considering overall antidepressant prescription rates in New Zealand, it is important to recognise that antidepressants (in particular SSRIs) are also commonly used to treat anxiety. Anxiety disorders are the most common mental health problem in New Zealand (14.8% 12-month prevalence), followed by mood disorders such as depression (7.9%) and substance abuse (3.5%) (Oakley Browne, Wells, & Scott, 2006). It is therefore worth noting the significance of antidepressant prescriptions for anxiety disorders in contributing to the overall volume of antidepressant prescriptions in New Zealand. There is limited local research on antidepressant prescription practices in New Zealand, and available data are not currently linked to clinical information, such as the reason for prescription (e.g. for anxiety). Therefore, further research into the use of antidepressants, for example in the specific treatment of anxiety (Exeter et al., 2009), the duration of prescribing and the doses prescribed would be useful. Do antidepressants ‘work’? In recent years, significant public health efforts have aimed to address the burden of depression. In New Zealand, as in other countries, this has included the launch of awareness campaigns targeting depression, the development of suicide prevention strategies, and the introduction of primary care practitioner guidelines for the treatment of depression and other mood disorders.In the last two decades, new generation antidepressants have also been developed, which are marketed as clinically superior to older antidepressant types and widely endorsed as an appropriate first-line response to depression. However, it is not clear whether the apparent exponential increase in antidepressant prescriptions will counter the often-cited predictions that the global burden of depression will increase to become the second leading contributor to the global burden of disease (DALYs; Disability Adjusted Life Years) for all ages and both sexes by 2020. According to WHO (2011), ‘Today, depression is already the 2nd cause of DALYs in the age category 15–44 years for both sexes combined’. There appears to be little evidence that increasing the availability of antidepressants results in an overall reduction in mortality and morbidity associated with depressive disorders. Depression is increasingly recognised as a chronic condition with a tendency to recur (Simon, 2000; Andrews, 2001). As Dobson et al. (2008) noted, there is little evidence that antidepressants alter the course of depression, and there is a well-known risk of relapse once medication is withdrawn. The value of antidepressants in suicide prevention is also subject to debate, as clinical trials have not demonstrated that those taking antidepressants are less likely to attempt suicide than those receiving a placebo (Khan, Warner, & Brown, 2000) As Moncrieff and Kirsch (2005, p. 157) noted, ‘Antidepressants have not been convincingly shown to affect the long term outcome of depression or suicide rates’. Thus, evidence about the limited efficacy and therapeutic benefit of antidepressants has raised questions about the extent to which drug therapy alone can be relied upon as a response to depression. Since SSRIs were introduced in the 1990s, they have been medically promoted and marketed by industry to the public as drugs that have a specific effect on chemical pathways in the brain. Thus, the popularity of antidepressants can be seen to rest on an assumption that the drugs ‘work’ by having an active biochemical effect on the brain. However, within the clinical sphere, biochemical theories of 3 depression are recognised as unproven (Antonuccio, Danton, DeNelsky, Greenberg, & Gordon, 1999; Greenberg, 2010). A number of meta-studies have highlighted the significance of the placebo effect, and raised many questions about the extent to which antidepressants ‘work’ in a chemical sense. For example, in a meta-analysis of both published and previously unpublished trial data, Kirsch, Deacon, Huedo-Medina, Scoboria and Johnson (2008) found that SSRIs did not produce clinically significant differences from placebos in treating mild to moderate depression; a similar finding was made by Fournier et al. (2010). Both studies did note a clinically significant benefit of antidepressants over placebos in the treatment of severe depression, however. On the basis of these findings, the authors recommended that antidepressants should only be used when an alternative (i.e. non-drug) approach had been tried and failed, rather than as a first line response (Kirsch et al., 2008). Furthermore, as Moncrieff (2001, p. 293) has argued, ‘The fact that depressive conditions respond to a variety of psychotherapies also implies that recovery is not achieved through a particular biochemical manipulation’. However, other meta-analyses support the efficacy of antidepressants over and above placebos even for less severe forms of depression (see, for example, Arroll et al., 2009). The measurement of what constitutes a clinically significant pharmacological effect is also a hotly debated issue (NZGG, 2008). Historically, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were regarded as the ‘gold standard’ method for establishing the effectiveness of drugs such as antidepressants. However, in recent years, the previously accepted evidence base for the efficacy of antidepressants has come under clinical scrutiny, with some researchers arguing that early RCTs demonstrating the superiority of antidepressants over placebos were methodologically flawed, with a bias towards reporting on only positive findings, and so reliance on their findings results in continued overstatement of the efficacy of antidepressants (Moncrieff, 2001; Ministry of Health, 2007, p. 1; Mental Health Foundation, 2012). Pharmaceutical sponsorship of these clinical trials (and the withholding of unfavourable results) is seen as a further problem with the reliability of the current evidence base on antidepressants (Kirsch, Moore, Scoboria, & Nicholls, 2002; Kirsch et al. 2008). Thus, not only is there a lack of clinical consensus about the causality of depression, but there also appears to be a substantial gulf between public and clinical understanding of how antidepressants ‘work’ and the existing caveats on their efficacy. The context of antidepressant prescription in New Zealand In New Zealand and internationally, increases in antidepressant prescription have been attributed to an increased awareness of depression (both by clinicians and the general public), as well as the expanding range of conditions for which antidepressants are now prescribed, including anxiety, seasonal affective disorder and premenstrual syndrome (Hollinghurst, Kessler, Peters, & Gunnell, 2005). Further explanations have included lower prescription thresholds, stricter adherence to clinical guidelines leading to longer courses for first prescriptions, and an increasing rate of repeat prescriptions for chronic depression (Moore et al., 2009). While global trends of increasing prescription rates would seem to reflect a generalised clinical endorsement of the widespread use of antidepressants, clinical guidelines for practitioners increasingly include caveats on their use, citing recent evidence relating to limitations, risks and alternatives to antidepressants. For example, the most recent National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidance on the management of depression advises against the use of antidepressants in the first instance for mild depression due to a poor risk-benefit ratio (NICE, 2009). 4 Instead, it is advised that individuals with mild to moderate depression be offered a range of ‘low intensity psychosocial interventions’, including guided self-help (based on CBT principles), computerised cognitive behavioural therapy (CCBT), and a structured physical activity (NICE, 2009). New Zealand practitioner guidelines similarly recommend a conservative approach to the use of antidepressants in cases of mild to moderate depression (see, for example, NZGG. 2008, p. xv), which states that ‘psychological and pharmacological therapies are equally effective for treating adults with moderate depression’. International research suggests that while many GPs regard antidepressants as being of limited value and would prefer to refer patients with mild depression for non-drug therapies (including exercise therapy), they are primarily constrained due to limitations in availability and funding (Mental Health Foundation UK, 2005). This may go some way to accounting for the continuing trend of increasing prescription. Other research conducted by an independent medical research company in the United Kingdom found that 80% of GPs admitted to over-prescribing antidepressants, with three-quarters of GPs surveyed stating that they were prescribing more antidepressants than they did 5 years previously. GPs cited a lack of availability of psychological therapies for managing mild to moderate mental health conditions as the primary reason for this (Norwich Union Healthcare, 2004). Thus, while clinical guidelines increasingly encourage practitioners to take a cautious approach to prescribing and endorse encouraging the use of evidence-based alternatives, in reality many clinicians are not wellplaced to refer their patients to these treatment approaches, which do not currently receive the same level of subsidisation as drug treatments. Similarly, it is likely that New Zealand’s antidepressant prescription trends to some extent reflect a historical lack of access to alternative treatment approaches for depression, as prescriptions for antidepressant medication are heavily subsidised by the Government, while other approaches often require that users pay the full cost – and time with a private, experienced and qualified therapist or counsellor can cost around $100–150 per hour. The limited availability of psychological therapies in New Zealand is now being recognised (e.g. Peters, 2007; Te Pou O Te Whakaaro Nui, 2009) and there have been recent moves to increase access to these services within the primary care setting. There is not currently the provision for general practitioners to refer patients for subsidised depression counselling, however. Although the total funding is $23m per year, this does not cover every general practice and tight criteria are applied by each Primary Health Organisation (PHO) to ensure that the services offered are provided to those in highest need (Ministry of Health, email correspondence, 23 December 2011). In addition to referrals to private therapists or counsellors, a variety of other initiatives are also in place. This includes an 8-week computerised cognitive behavioural therapy (cCBT) programme called ‘Beating the Blues’, which has been funded since February 2011 and in which GPs can enrol their patients. There is also an online interactive tool for individual self-management of mild to moderate depression (‘The Journal’). With an increasing number of New Zealanders now online (86% in 2011; www.aut.ac.nz/research/research-institutes/icdc/projects/world-internet-project, retrieved 11 January 2012), this will be an option for most New Zealanders. Mental health problems are commonly seen in the primary care (i.e. general practice) setting and are clinically recognised as a major cause of disability in the general population (NZGG, 2008). The Ministry of Health (2008, p. 1) noted that ‘Mental disorders are extremely common in the general practice setting, with over one third of adults attending primary care likely to have met the criteria for a DSM-IV diagnosis within the past 12 months’. It is increasingly recognised that the burden of disease 5 associated with depression vastly exceeds the capacity of specialist services. As Lillis, Mellsop and Dutu (2008, p. 30) noted, ‘Recognition of this mismatch between total community psychiatric morbidity and available specialist resources has led to worldwide commitments to increasing the delivery of skilled mental health care within the setting of primary care’. Following this view, the primary care setting is increasingly being recognised as an appropriate forum for initiatives in mental health care and promotion in New Zealand. The development of primary mental health initiatives also reflects the Goals of the Primary Health Care Strategy (Ministry of Health, 2001) as a strategic approach with an emphasis on population health, health promotion/preventive care and community-led initiatives (Dowell et al., 2009). The general practice setting is also recognised as important for the early recognition of mental health problems, due partly to the continuity of contact between patients and their GP (Reid, 2005). The Ministry of Health (2008, p. xv) noted that ‘Routine psychosocial assessment is the key to improving the recognition of common mental disorders’, and general practitioners are increasingly seen as ideally placed to detect and treat mental illness at an early stage. Other recognised benefits of a primary care approach to mental health care include affordability and accessibility of treatment, the capacity for health promotion, and the potential for integration of physical and mental health care in terms of offering a more holistic package of care (Dowell et al., 2009). GPs act as a ‘gateway’ to mental health services in New Zealand, with the exception of crisis presentations (MaGPIe Research Group, 2005). The majority of individuals with mental health problems in New Zealand will access the healthcare system via their GP and have their problem managed in that setting, with some patients referred from there to secondary or tertiary settings (Reid, 2005). New Zealand literature suggests that GPs deliver around three-quarters of the treatment for mental health disorders in New Zealand (MaGPIe Research Group, 2003). A 2003 study undertaken by the MaGPIE (Mental Health and General Practice Investigation Research) group at the University of Otago found that 36% of those attending their GP had one or more of the three most common mental health problems – anxiety, depression and substance use/dependence (in descending order of frequency), with a frequent occurrence of co-morbidity (MaGPIe Research Group, 2003). This research noted a reluctance among patients to disclose psychological problems to their GP, with the vast majority of patients with mental health issues not presenting this to their GP as the main reason for their appointment. Surveyed GPs felt that roughly half of those attending had experienced some degree of psychological problems in the previous year, although not necessarily at the level of diagnosis. In New Zealand, these mental health problems are not evenly distributed in society, with certain ethnic groups (specifically Māori and Pasifika peoples) having markedly higher rates of mental health problems (Dowell et al., 2009). In New Zealand, barriers to the effective use of GPs in depression care (including cost effectiveness) have been increasingly recognised within the public health sector in recent years. A number of measures have been proposed and trialled for improving GP knowledge and skill in depression care, as well as for increasing public ‘mental health literacy’ and de-stigmatisation of mental illness (MaGPIe Research Group, 2005, p. 634). The primary mental health initiatives currently being implemented in New Zealand, including the provision of a short course of talking therapy sessions, have been positively evaluated and well received by consumers (Dowell et al., 2009). A large, unmet need for psychotherapeutic intervention in primary care has been noted. Given the prohibitive cost of private counselling in New Zealand, it would be valuable to extend existing primary mental health counselling initiatives to allow access to a 6 greater proportion of the general population. Through broadening access to non-drug therapies for depression, this may conceivably result in a reduction in the national antidepressant prescription rate. Risks associated with antidepressants In the literature, side effects are reported to be a very significant problem associated with antidepressant use, with 30–60% of those prescribed antidepressants discontinuing treatment for this reason (Antonuccio et al., 1999). Hu et al. (2004) found that clinicians tend to underestimate how troublesome these side effects are for their patients. SSRIs are often prescribed in preference to other antidepressant types because they are considered to be safer in terms of adverse effects and consequences of overdose (Wessley & Kerwin, 2004; Exeter et al., 2009). However, unpleasant side effects including sexual dysfunction and drowsiness (Hu et al., 2004), sleep disturbance (Armitage, 2000; Ferguson, 2001), weight gain (Mansand & Gupta, 2002), and gastro-intestinal problems such as nausea are still widely reported and experienced by up to 50% of patients using SSRIs (Antonuccio et al., 1999; Ferguson, 2001). Unpleasant withdrawal symptoms (i.e. discontinuation syndrome) are also a well-documented issue for all antidepressant types, including SSRIs (Ferguson, 2001). Over and above the occurrence of troublesome side effects, a safety concern related specifically to SSRI use is the risk of drug reactions, specifically serotonin syndrome. This reaction causes the body to produce too much serotonin, resulting in potentially life-threatening symptoms, including increased heart rate, delirium, overactive reflexes and agitation, increased body temperature, and hallucinations (Boyer & Shannon, 2005). There is greatest risk of the syndrome when first starting an SSRI, when other drugs are being taken alongside SSRIs, when medications are changed, and when there is intentional or unintentional overdose (Ferguson, 2001). While SSRIs are considered to be a safer class of antidepressant than older types, Antonuccio et al. (1999) reported that they are frequently (more than 50% of the time) prescribed alongside other psychotropic medications, resulting in increased risk of reactions such as serotonin syndrome. Other safety concerns associated with antidepressant medication relate to associated risks of suicide, suicidal ideation and intentional self-harm. There appears to be widespread clinical support for the value of antidepressants in preventing suicide, with a view that increasing the use of antidepressants will result in a reduction in the suicide rate (e.g. Exeter et al., 2009; Mulder, Joyce, Frampton, & Luty, 2008). Ministry of Health research on antidepressant prescription patterns in New Zealand supports this, noting a significant decline in suicide rates since the introduction of SSRIs (Ministry of Health, 2007). However, international literature in this area shows ongoing debate about the evidence base for the value of antidepressants in suicide prevention, with some arguing that a conclusive link has not been demonstrated (e.g. Khan et al., 2000; Safer & Zito, 2007). Antidepressants are also the medication most commonly used in suicide by poisoning (Kapur, Mieczkowski, & Mann, 1992), with the most recent available New Zealand data citing coronial records for 2001, which showed that 200 poisoning deaths were directly attributable to, or involved, antidepressants (146 intentional and 54 unintentional deaths) (Reith et al., 2003). It should be noted that SSRI medications are less likely to be lethal in overdose than other types; nonetheless, the literature notes an ongoing concern about possible links between SSRI use and suicide and self-harm. Of particular concern has been the question of increased risk for children and adolescents. In New Zealand in 2004, the medicines regulatory authority MEDSAFE advised the prescriber of an unfavourable risk/benefit ratio for prescribing SSRIs (other than Fluoxetine) to children and adolescents (MEDSAFE, 2004). This 7 followed the issuing of a statement by the US Food and Drug Administration requiring antidepressant labelling to indicate increased risk of suicide, particularly in these groups; subsequently in 2005, a further advisory was issued about the need to closely monitor adults taking SSRIs for suicidal thoughts. Clinical protocols now tend to advise against the use of antidepressants as a first-line approach in treating depression in children and adolescents; however, there is ongoing debate with respect to suicidality and use in adults. Moncrieff and Kirsch (2005) noted that meta-analyses of data from antidepressant drug trials have not found any difference in suicide rates between drug and placebo groups, and Didham, McConnell Blair, & Reith (2005) did not find a direct link between SSRI use and suicide in New Zealand, and suggested that causality is complex and more likely related to the underlying condition: ‘Overall the results of this study suggest that the more depressed patients are prescribed SSRIs, therefore these drugs appear to show a greater risk of self-harm and suicide. However the real risk factors are more likely to be depression and suicidal ideation’. However, this research and the Ministry of Health (2007) study did note a statistically significant association between increased prescription rates of SSRIs and increased rates of hospitalisation for intentional self-harm in New Zealand. Fluoxetine, one of the two most widely prescribed SSRIs, was shown to be associated with the highest increased risk of hospitalisation for intentional self-harm, with the Ministry’s figures showing that in 2005, 3113 of the 80,829 patients being prescribed Fluoxetine were hospitalised (Ministry of Health, 2007). This increased risk of self-harm may not be widely recognised in the public domain as a significant risk associated with SSRI use. Another area of risk noted in the literature relates to health risks associated with long-term antidepressant use. Long-term prescription rates are significantly higher than in previous decades, and appear to account for a substantial amount of the overall increase in prescribing (Moore et al., 2009). Indeed, individuals with recurring depression are often encouraged to remain on medication indefinitely (Dobson et al., 2008). A study by Cruickshank et al. (2008) found that more than half of the patients on longer-term antidepressants did not meet the criteria for a psychiatric diagnosis, raising the question of the need for on-going review in cases of long-term prescribing. Related studies similarly have signalled concerns over inadequacies in clinical review in cases of long-term prescribing (Petty, House, Knapp, Raynor, & Zermansky, 2006; Leydon, Rodgers, & Kendrick, 2007). Research suggests that, in some cases, individuals may wish to stay on antidepressants to avoid withdrawal effects, or due to a lack of clinical encouragement/support to discontinue their medication (Petty et al., 2006; Leydon et al., 2007; Moore et al., 2009). While repeat, long-term prescribing is used as a strategy to manage the problem of recurrence, evidence is emerging that long-term use may actually have a ‘pro-depressant’ effect in some individuals, causing permanent, treatment-resistant depression (Fava, 2003; El-Mallakh, Gao, Briscoe, & Roberts, 2010; Andrews et al., 2011; El-Mallakh, Gao, & Roberts, 2011). This proposed syndrome of drug-induced chronic depression is termed tardive dysphoria or oppositional tolerance. It is thought that irreversible changes to drug receptors in the brain occur after long-term use, causing the brain to make compensatory adaptations to restore normal functioning, resulting in increased biochemical vulnerability to depression thereafter. Given the growing clinical consensus that antidepressants offer no significant clinical benefit in cases of mild to moderate depression, the emerging evidence about the risk of antidepressant use inducing chronic depression adds compelling weight to the view that antidepressant therapy should, if possible, be avoided as a first-line response to less severe types of depression. It has also been suggested that 8 where antidepressants are prescribed, guidelines for maintenance therapy (i.e. to prevent relapse after resolution of the initial acute episode) should be reviewed in light of such risks (Andrews, Kornstein, Halberstadt, Gardner, & Neale, 2011). Evidence of a dramatic increase in antidepressant treatment resistance since the 1990s (El-Mallakh et al., 2010) suggests that repeat prescription is probably widespread, and so there is potential for a large number of cases of untreatable druginduced chronic depression to emerge as a serious public health issue in the future. Evidence-based alternatives to antidepressants Prior to the advent of widespread antidepressant use, psychotherapeutic approaches were a significant component of psychiatric practice in North America (Greenberg, 2010). However, there has been a continued decline in the availability of psychotherapy as a treatment option (Olfson & Marcus, 2010). While popular demand for antidepressants is often cited as having fuelled increasing prescription rates, evidence suggests that those on the receiving end of depression treatment generally have a strong preference for talking therapies and self-help approaches over drug treatment, and consider these approaches to be highly effective (Antonuccio et al., 1999; Jorm, 2000; van Schaik et al., 2004). As van Schaik et al. (2004) noted, part of this preference relates to a view that talking therapies address the core reasons for depression, while antidepressants have unpleasant side-effects and a risk of addiction. For the treatment of more severe forms of depression, there is a clear evidence base for the value of medication, with meta-analyses confirming clinically significant benefits over placebos (Kirsch et al., 2008; Fournier et al, 2010). However, psychological therapies, in combination with drug treatment, are still recognised as having a valuable role even when treating severe depression, with clinical protocols stating that a combined approach is more useful than medication alone (NICE, 2004). Psychological therapies are now well-recognised as being effective in treating a range of mental health problems, including depression, anxiety, addiction and social phobias, and this approach is widely endorsed within the mental health sector (Mental Health Foundation UK, 2006; Mental Health Commission, 2007). This endorsement is underpinned by a substantial and ever-increasing scientific evidence base for non-pharmacological approaches to depression care, in particular cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which currently has the largest body of scientific support. Such treatment is now recognised as being equally effective to antidepressants in the treatment of mild to moderate depression (Mental Health Foundation UK, 2008; NZGG, 2008; Exeter et al., 2009; Segal et al., 2010); for a review of relevant literature, see DeRubeis and Crits-Christoph (1998). Mindfulness is another emerging evidence-based practice that can be learned in group settings, and which can reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety, decrease risk factors such as chronic psychological stress, and be a protective factor for future mental health (Mental Health Foundation, 2011). A key therapeutic benefit of pshychological therapies over drug treatment is their long-lasting effect and value in preventing relapse of depression (Fava, 2004; Hollon et al., 2005). A 2006 meta-analysis on CBT showed that depression relapse rates for those treated with CBT were half that of those treated with drugs alone (Butler, Chapman, Forman, & Beck, 2006). Occupational health research also shows that CBT helps people with depression to stay in employment (Seymour & Grove, 2005). Another benefit of non-pharmacological approaches is the avoidance of side effects (Antonuccio et al., 1999), which, as noted earlier, may not be well-recognised by clinicians as a problem for those taking medication. 9 However, despite the available evidence base for psychological therapies, historically there have been several barriers to the integration of these approaches into mainstream depression care. Psychological therapies have often been viewed as having an unfavourable cost-benefit ratio compared with medication. However, there is some evidence to suggest that approaches such as CBT are more cost-effective in the long term, as they have longer lasting benefits than medication (Antonuccio, Thomas, & Danton, 1997; Hollon et al., 2005; Dobson et al., 2008). As Bosmans et al. (2008) noted, there is growing evidence that the overall cost-effectiveness of treatment for depression could be improved by wider use of these treatments. Psychological approaches also do not currently have comparable scientific or popular status or credibility to antidepressants as an effective treatment for depression (Greenberg, 2010). Clinical advocates for the value of psychological therapies continue to argue that the current landscape of depression treatment has been substantially shaped by the interests of pharmaceutical companies, through sponsorship of drug research and trials, selective publication of trial results, and more broadly through historic involvement in the framing of depression as a biochemical problem (Moncrieff, 2008; Greenberg, 2010. (See Mental Health Foundation (2012) for further discussion around the aetiology of depression and its treatment.) This, arguably, accounts for the continued ideological and financial bias towards pharmacological responses to depression, which, in turn, may be reflected in a lack of institutional will to implement the necessary infrastructure for ‘mainstreaming’ psychological therapies. As Hollinghurst et al. (2005) have suggested, ‘Increases in the pharmacological treatment of depression have not been matched by the development of psychological services of proved effectiveness, which may reflect the absence of a powerful body, equivalent to the pharmaceutical industry, to promote their development and use’. Within New Zealand, although CBT is endorsed as effective and recommended to be delivered in the primary care setting by a range of practitioners (Mental Health Commission, 2007), access to CBT and other evidence-based psychological therapies is still very limited and, when available, is recognised as extremely variable in terms of regional availability, practitioner training level and cost of service (Mental Health Commission, 2007). In other countries, GP referral to psychological therapies is receiving substantial funding boosts. For example, in the United Kingdom, NICE has recommended that a range of psychological therapies be made available on the National Health Service (NHS), and in 2011 the United Kingdom Government announced plans to substantially increase the availability of free psychological therapies on the NHS, making available a choice of several different approaches (CBT, Counselling for Depression and Interpersonal Therapy), and also allowing for self-referral by GP patients (NICE, 2011). This amounts to an investment of ₤400 million in addition to existing funding. Similarly, Australia and Scotland plan to increase investment in the use of talking therapies in both primary and secondary care (Mental Health Commission, 2007). Within New Zealand, there is consensus among clinicians and service users that further improved access to psychological therapies is needed (RANZCP, 2004; Peters, 2007; Te Pou O Te Whakaaro Nui, 2009), and recognition of the need for development and expansion of such services in the primary care setting (Dowell et al., 2009). More substantial investment into increasing the availability of free or subsidised psychological therapies via PHOs at a national level in New Zealand would, therefore, seem timely. 10 Conclusions This paper raises questions about whether current levels of antidepressant prescribing are scientifically justified. This is an area of ongoing scientific and clinical debate, but such questions have only recently begun to be aired in the public domain. It is clear that the popular view of depression as fundamentally a medical problem, i.e. due to a chemical imbalance and requiring a chemical response, rests on an evidence base that is subject to ongoing debate within the clinical domain, as it continues to exclude a large body of data on proven alternatives to medication, and reflects an ongoing lack of intellectual and financial investment in this area. This means that currently many people with depression may not be receiving the help that best fits their needs, and additionally may be being exposed to side effects and health risks. Given the current lack of access to non-drug treatments, and the evidence relating to the risks and side effects of antidepressants, it is possible that the high rates of antidepressant prescription in New Zealand may be more a result of a lack of availability of alternatives rather than the efficacy or tolerability of these drugs. There is also evidence that consumers would often prefer non-pharmacological treatments for depression. Guidance for New Zealand GPs in treating depression states that ‘planned treatment for depression should reflect the individual’s values and preferences and the risks and benefits of different treatment options’ (NCGG, 2008, p. xv); for this commitment to take pragmatic effect, current funding would need to be extended so that talking therapies could be made available in the primary care setting to all GP patients. Meta-analyses of SSRI drug trials demonstrate a lack of significant clinical benefit in the use of antidepressants to treat mild to moderate depression. Nonethless, in New Zealand and internationally, prescription rates continue to increase, suggesting an urgent need to re-evaluate the public health gains of antidepressants in reducing the individual and social burden of depression, and to consider the apparent disconnect between evidence base, clinical protocols and clinician prescription practices ‘in the field’. Similarly, increased public awareness of the drawbacks of antidepressants may be required to challenge prevailing popular beliefs about the superiority of drug therapies over other evidence-based treatments for depression. Recent initiatives to strengthen the primary mental health sector in New Zealand offer a timely opportunity for public education in this area. There is evidence that Māori and Pasifika peoples are less likely to access mental health services in New Zealand. Targeted funding for psychological therapies would be a positive attempt to address such inequalities in mental health outcomes in this country. In addition, the fact that these groups receive antidepressant treatment for depression far less frequently than European/Pākehā New Zealanders may offer an interesting opportunity to observe the value of psychological approaches in this group in comparison with other groups. An evidence-based approach to the treatment of depression suggests that extending these initiatives to the general population would result in significant public health gains, by relieving the individual and social burden of depression in New Zealand, and reducing morbidity associated with antidepressant use. 11 References Andrews, G. (2001). Should depression be managed as a chronic disease? British Medical Journal, 322, 419. Andrews, P., Kornstein, S., Halberstadt, L., Gardner, C., & Neale, M. (2011). Blue again: Perturbational effects of antidepressants suggest monoaminergic homeostasis in major depression. Frontiers in Psychology, 2(159), 1–24. Antonuccio, D., Danton, W., DeNelsky, G, Greenberg, R., & Gordon, J. (1999). Raising questions about antidepressants. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics, 68, 3–14. Antonuccio, D., Thomas, M., & Danton, W. (1997). A cost-effectiveness analysis of cognitive behaviour therapy and fluoxetine (Prozac) in the treatment of depression. Behaviour Therapy, 28, 187–210. Arroll, B., Elley, C., Fishman, T., Goodyear-Smith, F., Kenealy, T., Blashki, G., Kerse, N., & MacGillivray, S. (2009). Antidepressants versus placebo for depression in primary care. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD007954. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007954. Arroll, B., Goodyear-Smith, F., & Lloyd, T. (2002). Depression in patients in an Auckland general practice. New Zealand Medical Journal, 115, 176–179. Armitage, R. (2000). The effects of antidepressants on sleep in patients with depression. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 45(9), 803–809. Baxter, J., Kokaua, J., Wells, J., McGee, M., & Browne, M. (2006). Ethnic comparisons of the 12 month DSM-IV disorders in Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand Mental Health Survey. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40, 905–913. Bosmans, J., van Schaik, D., de Bruijne, M., van Hout, H., van Marwijk, H., van Tulder, M., & Stalman, W. (2008). Are psychological treatments for depression in primary care cost-effective? Journal of Mental Health Policy & Economics, 11(1), 3–15. Boyer, E., & Shannon, M. (2005). The serotonin syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine, 352, 1112–1120. Butler, A., Chapman, J., Forman, E., & Beck, A. (2006). The empirical status of cognitive-behavioural therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 17–31. Cruickshank, G., MacGillivray, S., Bruce, D., Mather, A., Matthews, K., & Williams, B. (2008). Crosssectional survey of patients of long-term repeat prescription for antidepressant drugs in primary care. Mental health in Family Medicine, 5(2), 105–109. DeRubeis, R., & Crits-Christoph, P. (1998). Empirically supported individual and group psychological treatments for adult mental disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 37–52. 12 Didham, R., McConnell, D., Blair, H., & Reith, D. (2005). Suicide and self-harm following prescription of SSRIs and other antidepressants: Confounding by indication. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 60(5), 519–525. Dijkstra, A., & Jaspers, M. (2008). Psychiatric and psychological factors in patient decision making concerning antidepressant use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 149–157. Dobson, K., Hollon, S., Dimidjian, S., Schmaling, K., Kohlenberg, R., Gallop, R., …. Jacobson, N. (2008). Randomized trial of behavioural activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the prevention of relapse and recurrence in major depression. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 76(3), 468–477. Dowell, A.C., Garrett, S., Collings, S., McBain, L., McKinlay, E., & Stanley, J. (2009). Evaluation of the Primary Mental Health Initiatives: Summary report 2008. Wellington: University of Otago and Ministry of Health. El-Mallakh, R., Gao, Y., Briscoe, B., & Roberts, J. (2010). Antidepressant-induced tardive dysphoria. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics, 80, 57–59. El-Mallakh, R., Gao, Y., & Roberts, R. (2011). Tardive dysphoria: The role of long term antidepressant use in inducing chronic depression. Medical Hypotheses, 76, 769–773. Exeter, D., Robinson, E., & Wheeler, A. (2009). Antidepressant dispensing trends in New Zealand between 2004 and 2007. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 43, 1131–1140. Fava, G. (2003). Can long-term treatment with antidepressant drugs worsen the course of depression? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 64, 123–133. Fava, G. (2004). Six-year outcome of cognitive behavioural therapy for prevention of recurrent depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 468–477. Ferguson, J. (2001). SSRI antidepressant medications: Adverse effects and tolerability. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 3(1), 22–27. Fournier, J.C., DeRubeis, R.J., Hollon, S.D., Dimidjian, S., Amsterdam, J.D., Shelton, R.C., & Fawcett, J. (2010). Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: A patient-level metaanalysis. Journal of the American Medical Association, 303(1), 47–53. Greenberg, G. (2010). Manufacturing depression: The secret history of a modern disease. New York: Simon & Schuster. Gunnell, D., & Ashby, D. (2004). Antidepressants and suicide: What is the balance of benefit and harm. British Medical Journal, 329, 34. Hollinghurst, S., Kessler, D., Peters, T., & Gunnell, D. (2005). Opportunity cost of antidepressant prescribing in England: Analysis of routine data. British Journal of Medicine, 330, 1000–1001. 13 Hollon, S., DeRubeis, R., Shelton, R., Amsterdam, J., Salomon, R., O’Reardon, J., … Gallop, R. (2005). Prevention of relapse following cognitive therapy vs medication in moderate to severe depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 417–422. Hu, X., Bull, S., Hunkeler, E., Ming, E., Lee, J., Fireman, B., & Markson, L. (2004). Incidence and duration of side effects and those rated as bothersome with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment for depression: Patient report versus physician estimate. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 65(7), 959–965. Jorm, A. (2000). Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry, 177, 396–401. Khan, A., Warner, H., & Brown, W. (2000). Symptom reduction and suicide risk in patients treated with placebo in antidepressant clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57, 311–324. Kapur, S., Mieczkowski, T., & Mann, J. (1992). Antidepressant medications and the relative risk of suicide attempt and suicide. Journal of the American Medical Association, 268(24), 3441–3445. Kirsch, I., Deacon, B., Huedo-Medina, T., Scoboria, A., & Johnson, B.T. (2008). Initial severity and antidepressant benefits: A meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration. PLoS Med, 5, e45. Kirsch, I., Moore, T.J., Scoboria, A., & Nicholls, S.S. (2002). The emperor’s new drugs: An analysis of antidepressant medication data submitted to the US Food and Drug Administration. Prevention & Treatment, 5(23). Leydon, G., Rodgers, L., & Kendrick, T. (2007). A qualitative study of patient views on discontinuing long-term selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Family Practice, 24(6), 570–575. Lillis, S., Mellsop, G., & Dutu, G. (2008). General practitioners’ views on the major psychiatric classification systems. New Zealand Medical Journal, 121(1286), 30–36. Lucire, Y., & Crotty, C. (2011). Antidepressant-induced akathisia-related homicides associated with diminishing mutations in metabolizing genes of the CYP450 family. Pharmacogenomics and Personalized Medicine, 4, 65–81. MaGPIe Research Group (2003). The nature and prevalence of psychological problems in New Zealand primary healthcare: A report on Mental Health and General Practice Investigation (MaGPIe). Journal of the New Zealand Medical Association, 116(1171). MaGPIe Research Group (2005). Do patients want to disclose psychological problems to GPs? Family Practice, 22(6), 631–637. Mansand, P., & Gupta, G. (2002). Long-term side effects of newer-generation antidepressants: SSRIs, Vanlafaxine, Nefazodone and Mirtazapine. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 14(3), 175–182. MEDSAFE (2004). www.medsafe.govt.nz/hot/Alerts/NZSSRIdoctorletter.pdf retrieved 30 January 2012 14 Mental Health Commission (2007). Te Haererenga mo te whakaoranga 1996–2006. Wellington: Mental Health Commission. Mental Health Foundation (2011). An overview of mindfulness-based interventions and their evidence base. Unpublished report. Wellington: Mental Health Foundation. Mental Health Foundation (2012). Is depression at epidemic levels? Unpublished report. Wellington: Mental Health Foundation. Mental Health Foundation UK (2005). Up and running: Exercise therapy and the treatment of mild or moderate depression in primary care. London: Mental Health Foundation. Mental Health Foundation UK (2006). We need to talk: The case for psychological therapy on the NHS. London: Mental Health Foundation. Ministry of Health (2007). Patterns of antidepressant drug prescribing and intentional self-harm outcomes in New Zealand: An ecological study. Public Health Intelligence Occasional Bulletin No. 43. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Ministry of Health (2008). Identification of common mental disorders and management of depression in primary care. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Ministry of Health (2009). Towards optimal primary mental health care in the new primary care environment: A draft guidance paper. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Moncrieff, J. (2001). Are antidepressants overrated? A review of methodological problems in antidepressant trials. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 189(5), 288–295. Moncrieff, J. (2008). The creation of the concept of an antidepressant: An historical analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 66(11), 2346–2355. Moncrieff, J., & Kirsch, I. (2005). Efficacy of antidepressants in adults. British Medical Journal, 331(7509), 155. Moore, M., Yuen, H.M., Dunn, N., Mullee, M.A., Maskell, J., & Kendrick, T. (2009). Explaining the rise in antidepressant prescribing: A descriptive study using the general practice research database. British Medical Journal, 339, b3999. Mulder, R., Joyce, P., Frampton, C., & Luty, S. (2008). Antidepressant treatment is associated with a reduction in suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 118, 116–122. Murphy, G., Kremer, C., Rodrigues, H., & Schatzberg, A. (2003). Pharmacogentics of antidepressant medication intolerance. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(10), 1830–1835. Murray, C., & Lopez, A. (1997). Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet, 349, 1498–1504. 15 NICE (2004). Depression: Management of depression in primary and secondary care. National Clinical Practice Guideline Number 23. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence UK. NICE (2009). The treatment and management of depression in adults. NICE Clinical Guideline 90. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence UK. NICE (2011). Press release: Cash boost for psychological therapies to treat mental health. www.nice.org.uk/newsroom/news/CashBoostForPsychologicalTherapiesToTreatMentalHealth.jsp\, retrieved 29 September 2011. Norwich Union Healthcare (2004). Guide to services for a healthy mind. Norwich Union Health Care/Dr Foster. NZGG (2008). Identification of common mental disorders and management of depression in primary care. Wellington: New Zealand Guidelines Group. Oakley Browne, M., Wells, J., & Scott, K. (2006). Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand Mental Health Survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Olfson, M., & Marcus, S. (2010). National trends in outpatient psychiatry. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(12), 1456–1463. Peters, J. (2007). “We need to talk”: Talking therapies – a snapshot of issues and activities across mental health and addiction services in New Zealand. Auckland: Te Pou. Petty, D., House, A., Knapp, P. Raynor, T., & Zermansky, A. (2006). Prevalence, duration and indications for prescribing of antidepressants in primary care. Age & Ageing, 35, 523–526. Prator, B.C. (2006). Serotonin Syndrome. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 38(2), 102–105. RANZCP (Royal Australian & New Zealand clinical practice guidelines team for depression) (2004). Australian & New Zealand clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of depression. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 38, 389–407. Reid, J. (2005). Mental health treatment at the New Zealand GP. New Zealand Medical Journal, 118(1222). Reith, D., Fountain, J., Tilyard, M., & McDowell, R. (2003). Antidepressant poisoning deaths in New Zealand for 2001. New Zealand Medical Journal, 116(1184). Safer, D., & Zito, J. (2007). Do antidepressants reduce suicide rates? Public Health, 121(4), 274–277. Segal, Z.V., Bieling, P., Young, T., MacQueen, G., Cooke, R., Martin, L., Bloch, R., & Levitan, R. (2010). Antidepressant monotherapy vs sequential pharmacotherapy and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, or placebo, for relapse prophylaxis in recurrent depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(12), 1256–1264. 16 Seymour, L., & Grove, B. (2005). Workplace interventions for people with common mental health problems. London: British Occupational Health Research Foundation. Simon, G. (2000). Long-term prognosis of depression in primary care. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 78(4), 439–445. Summerfield, D. (2006). Depression: Epidemic or pseudo-epidemic? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 99, 161–162. Te Pou O Te Whakaaro Nui / The National Centre of Mental Health Research, Information and Workforce Development (2009). A Guide to talking therapies in New Zealand. Auckland: Te Pou. Van Schaik, D.J.F., Klijn, A.F.J., Van Hout, H.P.J., Van Marwijk, H.W.J., Beekman, A.T.F., De Haan, M., & Van Dyck, R. (2004). Patients’ preferences in the treatment of depressive disorder in primary care. General Hospital Psychiatry, 26(3), 184–189. Wessley, S., & Kerwin, R. (2004). Suicide risk and the SSRIs. Journal of the American Medical Association, 292(3), 379–381. WHO (World Health Organization) (2001). The World Health Report 2001: Mental health: New understanding, new hope. Geneva: Office of Publications< World Health Organization. WHO (World Health Organization) (2011) www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/definition/en/, retrieved 15 December 2011. 17