Prehistoric Art: Paleolithic & Neolithic Periods

advertisement

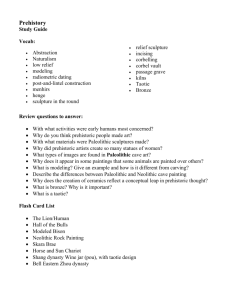

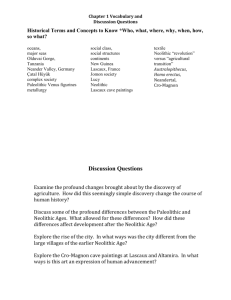

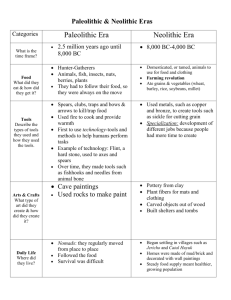

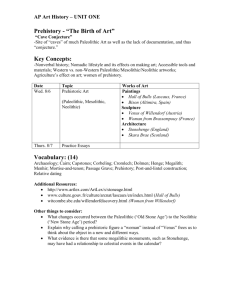

1 PART I THE ANCIENT WORLD CHAPTER 1 PREHISTORIC ART Paleolithic Art Key Images Wounded Bison, Altamira, p. 3, 1.1 Lions and Bison, Chauvet Cave, p. 3, 1.2 Bear. Recess of the Bears, Chauvet Cave, p. 3, 1.3 Long-Eared Owl, Chauvet Cave, p. 4, 1.4 Chinese Horse, Lascaux Cave, p. 4, 1.5 Rhinoceros, Wounded Man, and Bison, Lascaux Cave, p. 4, 1.6 Spotted Horses and Human Hands, Pech-Merle Cave, p. 6, 1.8 Hall of the Bulls, Lascaux Cave, p. 7, 1.10 Hybrid figure with a human body and feline head, p. 8, 1.11 Two Bison, Le Tuc d′Audoubert Cave, p. 9, 1.14 Dame à la Capuche (Woman from Brassempouy), p. 11, 1.15 Woman of Willendorf, p. 12, 1.16 Upper Paleolithic painting, drawing, and sculpture appeared over a wide area of Eurasia, Africa and Australia between 40,000 and 10,000 BCE. The Lower and Middle Paleolithic periods extend back as far as 2 million years ago. While these earlier cultures did make patterned stone tools, they did not make representational imagery of any kind. Paleolithic peoples subsisted by hunting and gathering, yet they still found time to make art. The most striking images of Paleolithic art are the painted, incised, or sculpted animals on the rock surfaces of caves, many of which are very naturalistic. Most of the images are renderings of animal forms, and when the human form is depicted it is much more abstract. Major cave sites include those at Altamira, Lascaux and Chauvet. There is much speculation about the interpretation and function of art in prehistoric societies. The inaccessibility of many of the images suggests that they did not serve a purely decorative function. Instead these images may have served some ritual purpose (help in the hunt) or religious function (shamanism). 2 In addition to cave paintings, Paleolithic peoples produced carved and modeled sculptures and reliefs. Women were frequent subjects in prehistoric sculpture, often far outnumbering men as subject material. Many of these sculptures were fertility objects. Neolithic Art Key Images Neolithic plastered skull, Jericho, p. 13, 1.17 Early Neolithic wall and tower, Jericho, p. 13, 1.18 Human figures, Ain Ghazal, Jordan, p. 13, 1.19 View of Town and Volcano, Çatal Hüyük, p. 15, 1.22 Female and male figures, Cernavoda, p. 16, 1.23 Menhir alignments at Ménec, p. 17, 1.24 Stonehenge (aerial view), p. 18, 1.25 The Old Stone Age gradually gave way to a period known as the Neolithic or New Stone Age, dating from about 8000 BCE in the Near East and Asia and about 5000 BCE in Europe. Neolithic peoples began to settle down in permanent villages and engage in the cultivation of regular food sources and the maintenance of herds of domesticated animals. Pottery, weaving, spinning, as well as architecture of stone, mud bricks, and timber, contributed to a new mode of life. Important remains of Neolithic settlements have been excavated at Jericho, Ain Ghazal, and Çatal Hüyük. Houses in the early Neolithic city of Jericho were constructed of mud brick with stone foundations. The inhabitants of Jericho buried their dead beneath the floors of their homes with the skulls, reconstructed with tinted plaster, displayed above ground. This practice suggests a respect for the dead and possible ancestor worship. Jericho was heavily fortified with walls 5 feet thick and over 13 feet high, and surrounded by a wide ditch. Several towers were constructed in the wall, measuring 28 feet tall and 33 feet in diameter at the base with a staircase providing access to the summit. At Ain Ghazal, near Amman in Jordan, the sculptural tradition appears to be quite different from the one in Jericho. Thirty fragmentary plaster figures have been excavated dating to ca. 7500 BCE. These figures are constructed from reeds bound with cordage, covered in plaster, and then painted. As with the plaster skulls from Jericho, these figures could represent some form of ancestor worship, although as 3 some of the bodies have two heads, they could also have served some mythical function. The Neolithic community of Çatal Hüyük in Anatolia (modern Turkey) dates from ca. 7500 BCE. The town underwent at least 12 different building phases between 6500 and 5700 BCE, which demonstrates the growth of the city. The people of Çatal Hüyük lived in houses built of timber and mud bricks with stone foundations. There were no streets, and people traveled from house to house by ascending a ladder through the roof of the house and crossing on rooftops. The lack of streets made the perimeter of the city more defensible. As at Jericho, in Çatal Hüyük burials were beneath the floors of houses. Unlike Paleolithic cave paintings, which were executed directly on walls or ceilings, the images found in the homes at Çatal Hüyük were executed on plaster-covered walls. If a new painting was required, another layer of plaster was laid over the previous image, thus avoiding the superimposition seen in some Paleolithic cave paintings. Some of the rooms in Çatal Hüyük were decorated with references to fertility, including bulls’ horns and plaster breasts. There are also many scenes of animal hunts which include small human figures depicted much smaller than the large bulls or stags. During the Neolithic period, pottery, weaving, and some smelting of copper and lead began to be developed. Menhirs, dolmens, and cromlechs appear in the Neolithic period. While menhirs and dolmens were used to mark burial sites, cromlechs often suggested a ritual function. The most famous cromlech in Britain is Stonehenge. Key Terms/Places/Names Paleolithic culture Altamira Lascaux Chauvet modeling naturalism Neolithic megaliths Jericho Çatal Hüyük heel stone post-and-lintel reliefs ochre pigment composite images optical images fertility object sarsen dolmen cromlech menhir triliths bluestone 4 Discussion Questions 1. Discuss the ways in which art was used as a vehicle to link the physical with the spiritual world in Paleolithic and Neolithic communities. 2. Contrast the ways in which cave paintings change from the Paleolithic to the Neolithic periods. 3. What contributes to our uncertainty of the interpretation of female figures such as the Woman of Willendorf and the Woman from Brassempouy? 4. In your opinion, what accounts for the abstract design of these fertility objects? 5. Discuss the design and the various theories of the function of Stonehenge. 6. What were the major architectural developments of the Neolithic period? In what ways are we indebted to the architectural developments of this period? 7. What do the construction methods and building choices in Jericho tell us about the concerns of the people living there? Resources Books/Articles Clottes, Jean. Return to Chauvet Cave: Excavating the Birthplace of Art. The First Full Report. London: Thames & Hudson, 2003. Davenport, Demarest, and Michael A. Jochim. ″The Scene in the Shaft at Lascaux.″ Antiquity 62 (1988): 558–62. Davis, W. ″The Origins of Image Making.″ Current Anthropology 27 (1986): 193–216. Leroi-Gourhan, André. The Dawn of European Art: An Introduction to Paleolithic Cave Painting. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1982. Ramos, Pedro A. Saura, Matilde Múzquiz Pérez-Seoane, and Antonio Beltrán Martínez. The Cave of Altamira. New York: Harry Abrams, 1999. Ruspoli, Mario. The Cave of Lascaux: The Final Photographs. New York: Harry Abrams, 1987. Thomas, Julian. Understanding the Neolithic. New York: Routledge, 1999. DVDs NOVA: Secrets of Lost Empires—Stonehenge and Colosseum. (1996). 60 min. 5 www The Cave of Lascaux http://www.culture.gouv.fr/culture/arcnat/lascaux/en/ The Cosquer Cave http://www.culture.gouv.fr/culture/archeosm/en/fr-cosqu2.htm NOVA Easter Island http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/lostempires/easter/