Neumonía causada por una infección simultanea de moquillo

advertisement

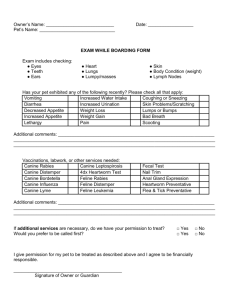

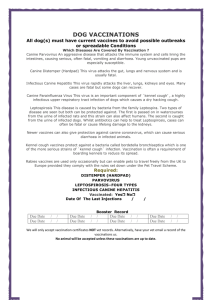

Short Communication Combined distemper-adenoviral pneumonia in a dog Luis E. Rodríguez-Tovar, Rafael Ramírez-Romero, Alicia M. Nevárez., Jxxxx J ZárateRamos and Alfonso López Departamento de Patología, Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia, UANL. Avenida Lázaro Cárdenas 4600 pte. Unidad Universitaria Mederos, Monterrey, N.L. CP 64930, México (Rodríguez-Tovar, Ramírez Romero, Valdez-Nava, Nevárez-Garza, Zárate-Ramos); Department of Pathology and Microbiology, Atlantic Veterinary College, UPEI. 550 University Avenue, Charlottetown, PEI, C1A4P3, Canada (López). Correspondence to Dr. A. López lopez@upei.ca 1 Summary A 2 ½-months-old, female, pug with history of anorexia, dyspnea, oculonasal discharge and seizures was submitted for postmortem examination with the tentative diagnosis of canine distemper. On necropsy the lungs had moderate crainoventral consolidation. Microscopically, there was necrotizing bronchointerstitial pneumonia with two distinct types of inclusion bodies. The fist type consisted of oval acidophilic and intracytoplasmic inclusions consistent with canine distemper virus (CDV) infection. The second type consisted of large intranuclear inclusion compatible with canine adenovirus type 2 (CAV-2). Also, intranuclear inclusion bodies were found in the cerebellar white matter. CDV and CAV-2 antigens tested positive in the lung by immunohistochemistry. Crystalline arrays consistent with CAV-2 were also observed by EM in the nuclei of the respiratory epithelium. Although dual CD and CAV-2 infection appear to be rare in dogs, a recent report suggests that combined infections are more common in some countries than previously suspected and confirmation should be done by histochemistry. 2 An 8-week-old female pug puppy purchased from a local kennel was taken to a local veterinarian for routine check-up and vaccination. On clinical examination the puppy appeared healthy and was vaccinated for distemper, ____ [listar agentes y nombre de la vacuna]. __ wks later a second boost was given to the puppy. ____ days after receiving the second vaccination the dog became lethargic, anorectic and started to developed dyspnea with bilateral serous oculonasal discharge. The dog was taken to the local veterinarian and was treated with antibiotics [cuales, dosis, via de administracion], vitamins [cuales, dosis I vía] and electrolytes [dosis y via]. The respiratory signs continued in spite of treatment and on day ___ after initial presentation the puppy developed neurologic signs characterized by rhythmic contraction of the masticatory muscles and progressive myoclonus. On day ___ the puppy started having recurrent episodes of seizures. Based on the respiratory and neurological signs canine distemper was suspected. ¿se hizo hematología? On day 25 the dog died and was submitted for postmortem examination to the Diagnostic Laboratory of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Nuevo León. At necropsy, the puppy was in fair bodily and showed moderate dehydration. [¿conjunctivitis o descarga nasal?] Significant postmortem findings were confined to the respiratory and lymphatic systems. The lungs had cranioventral consolidation affecting __% of the pulmonary parenchyma. [¿Se notó falta de colapso, impresiones costales o textura elástica que pudieran haber sugerido neumonía intersticial?]. On cut surface, purulent exudate was present in the major bronchi of the consolidated lung?. Severe atrophy of the palatine tonsils was also noted. No other gross lesions were observed and tissue samples from lung, lymph nodes, tonsils, heart, liver, spleen and brain were fixed in 10% buffered formalin solution for histopathological examination. Important microscopic lesions were restricted to the lungs and brain. The lungs exhibited severe necrotizing bronchiolitis characterized by swelling and exfoliation of epithelial cells that often resulted in segmental ulceration of the airway mucosa. Mitotic figures and non-ciliated flat cells consistent with proliferating cells at the early stages of repair were occasionally observed at the margins of ulcerated basement membranes. The bronchial and bronchiolar lumens contained many neutrophils admixed with macrophages and multinucleated syncytial giant cells (Fig 1). Numerous neutrophils were also present in the mucosa and submucosa of the airways, and the bronchial glands were distended and filled with neutrophils and cell debris. Some alveoli were packed with neutrophils, foamy macrophages and multinucleated cells and protein- rich edematous fluid. The most 3 remarkable alveolar lesion was a diffuse thickening of the walls because of type II pneumonocyte hyperplasia and interstitial edema. Numerous round to oval eosinophilic inclusion bodies were present in the cytoplasm of bronchial and bronchiolar cells, alveolar macrophages and multinucleated syncytial cells (Fig. 1). Another striking microscopic finding was the distinct presence of large basophilic inclusions in the nuclei of bronchial, bronchiolar and alveolar cells (Fig 2). Some of these basophilic inclusions filled the entire nucleus causing complete margination of the chromatin. Microscopic changes in the CNS were confined to the cerebellar white matter and consisted of multifocal neuropil vacuolation, astrocytic swelling and intranuclear acidophilic inclusions in glial cells. There was no evidence of perivascular infiltration of lymphocytes (perivascular cuffing) in the brain. Less significant microscopic lesions in other organs included a moderate lymphoid depletion, extramedullary hemopoieisis in the spleen and intranuclear and intracytoplasmic acidophilic inclusions in the epithelial cells of the renal pelvis. Based on the microscopic findings a diagnosis of dual canine distemper-adenovirus bronchointerstitial pneumonia was made. Paraffin-embedded lung was submitted to the Prairie Diagnostics in Saskatoon and tested by the avidin-biotine complex-peroxidase technique for canine distemper virus (CDV) and canine adenovirus-2 (CAV-2). Results revealed abundant morbillivirus antigen in the cytoplasm of the bronchial, bronchiolar, alveolar and glandular epitheliums (Fig. 1). Positive reaction was also observed in alveolar macrophages and multinucleated giant cells. In addition, CAV-2 antigen was detected in the nuclei of the bronchial epithelium, particularly in those cells that contained the large basophilic inclusions (Fig. 2). Thin paraffin sections of lung cut at 5 µm were deparaffinized and processed for transmission electron microscopy. Paracrystalline arrays of electrondense particles measuring 50 ± 2.0 nm in diameter were found in the nuclei of epithelial cells (Fig. 2). These electrondense particles were ultrastructurally consistent with CAV-2. Based on histopathology, histochemistry and electron microscopy the final diagnosis of dual CDV and CAV-2 infection was made in this puppy. It was not possible to ascertain the weather infection was related to the vaccination itself, to natural infection because the puppy was immune-incompetent or had maternal antiboides, or because the vaccine were ineffective (2). A recent report indicates that canine distemper in some countries like Japan is occurring with increasingly frequency in vaccinated dogs (3). 4 Bronchointerstitial pneumonias are frequently attributed to viral infections and to a much lesser extent to chemical and immunemediated injury to the lung (4,5). In the absence of inclusion bodies it is generally difficult to achieve etiological diagnosis in bronchointerstitial pneumonias. In this particular case however, the presence of two distinct types of pulmonary clearly make the tentative diagnosis in this puppy relative simple. Intracytoplasmic inclusions along with clinical history of respiratory and neurological signs are highly suggestive of canine distemper, while karyomegaly with large intranuclear basophilic inclusion bodies are most consistent with CAV-2 infection (6). Histochemistry proved rather valuable in confirming dual CDV and CAV-2 infection in this puppy since culture of these virus is difficult (1,6). The intralesional distribution of viral antigens in the bronchioles and alveoli was typical of bronchointerstitial pneumonia (4) At the early stages of infection viral antigens are centered in the areas of bronchiolar necrosis while in later stages of the disease the viral antigen is also present the alveolar macrophages as it was the case with this puppy (5,6). Exfoliated cells positively staining for CDV and to a lesser extent CAV-2 were present in the bronchiolar lumens. The mitotic activity along the denuded bronchiolar basement membranes and the hyperplasia of alveolar type II pneumonocytes clearly indicate that at the time of death the lung was undergoing repair (4,5). These findings were chronologically consistent with 2-3 wks history of respiratory distress 4). Canine distemper has a worldwide distribution and is particularly prevalent in geographic areas where vaccination is not routinely done. This disease is generally fatal since it affects the respiratory tract causing bronchointerstitial pneumonia, rhinosinusitis and conjunctivitis; the CNS causing non-suppurative encephalitis and demyelination; and the digestive tact causing gastroenteritis, diarrhea and dehydration (2,7). Although neuropil vacuolation and intranuclear inclusions in glial cells were present in the brain of this puppy, there was no histological evidence of perivascular lymphocytes which are typically seen in the non-suppurative encephalitis of canine distemper (7). CAV-2 is another highly contagious viral agent incriminated in canine respiratory tract disease, particularly in young dogs kept in crowded environment such as pet stores, boarding kennels and veterinary hospitals (kennel cough) (8). Infection with CAV-2 is generally transient and seldom fatal unless it is complicated with a secondary bacterial bronchopneumonia (5,8). In fatal cases, there is a severe bronchointerstitial pneumonia characterized by necrosis of the bronchiolar and alveolar epithelium, and in some cases, large intranuclear inclusion bodies are seen in bronchiolar and alveolar cells. Like canine 5 distemper, etiological diagnosis of CAV-2 infection is achieved by FAT, immunohistochemistry or viral isolation. The suppurative changes observed in the lungs of this puppy were consistent with as secondary bacterial pneumonia. Like many other respiratory viruses, CDV and CAV-2 impair the defense mechanisms and predisposes dogs, particularly young puppies, to secondary bacterial bronchopneumonia (5,8). Bordetella bronchiseptica is the most common cause of secondary bacterial pneumonia in dogs. Unfortunately, the lungs of this puppy were not cultured and therefore the cause of the suppurative bronchopneumonia remained unknown. It is possible that distemper encephalitis may have predisposed the puppy to aspiration pneumonia in spite the fact that food particles were not microscopically seen in the lung. Although frequently reported in dogs with CDV infection, there was no microscopic evidence of opportunistic infection in this puppy (4,9). A recent retrospective study of canine viral pneumonias conducted in Mexico revealed two important facts regarding CVD and CAV-2 infections in dogs. Firstly, single or combined respiratory infections involving CDV, CAV2 and canine parainfluenza (CPIV) occur more frequent in the canine population than previously thought (6). Secondly, histopathology alone is not always reliable as a diagnostic tool since inclusion bodies, the hallmarks for CDV and CAV-2 infections are not always present in the lung. This is particularly true during the late stages of the disease where inflammation and repair occurs and epithelial cells no longer exhibit inclusions. Although dual infections with CDV and CAV-2 as the one seen in this puppy are relatively rare, similar cases have been previously reported in Mexico and other countries (10-12). Bronchointerstitial pneumonia along with the two distinct types of inclusion bodies was almost conclusive of a dual viral infection in the puppy but routine laboratory confirmation always requires of immunohistochemistry. 6 References 1. Haines DM, West KH. Immunohistochemistry: forging the links between immunology and pathology. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2005;108:151-156. 2. Green CA, Apel MJ. Canine Distemper, In: Green, Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 2nd Edit., Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1998:9-20. 3. Lan NT, Yamaguchi R, Inomata A, Furuya Y, Uchida K, Sugano S, Tateyama S. Comparative analyses of canine distemper viral isolates from clinical cases of canine distemper in vaccinated dogs. Veterinary Microbiol 2006: xxx-xxx 4. Dungworth, D. L. The respiratory system. In: Pathology of Domestic Animals, Jubb, KV F, Kennedy PC and Palmer,N. Ed., 4th Edit., San Diego: Academic Press, 1993: 539-699. 5. Lopez, A. Respiratory system, thoracic cavity, and pleura. In: Thompson´s Special Veterinary Pathology, McGavin MD, Carlton WW and Zachary JF. 3rd Edit., St. Louis: Mosby, 2001:125-195. 6. Damian M, Morales E, SalasG, Trigo FJ. Immunohistochemical detection of antigens of distemper, adenovirus and parainfluenza viruses in domestic dogs with pneumonia. J Comp Pathol 2005;133: 289-293. 7. Summers BA, Cummings JF, De Lahunta A. Veterinary Neuropathology. Mosby. NY. 1995 8. Erles K, Dubovi EJ, Brooks HW, Brownlie J. Longitudinal study of viruses associated with canine infectious respiratory disease. J Clin Microbiol 2004; 42: 45244529. 9. Ramirez-Romero R, Gonzalez-Spencer D. Robinson RM, Eguiarte DJ. Tyzzer´s disease associated with distemper. A case report. Rev Vet Mexico, 1989;20:61-64. 10. Kobayashi, Y Ochiai, K, Itakura C. Dual infection with canine distemper virus and infectious canine hepatitis virus (canine adenovirus type 1) in a dog. J Vet Med Sci 1993;55:699-701 11. Ducatelle R, Maenhout, D, Coussement W, Hoorens J. Dual adenovirus and distemper virus pneumonia in a dog. Vet Quart 1982;4:84-88. 12. Stookey, JL VanZwietn MJ Whitney G.D. Dual viral infections in two dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1972;161:1117-1121. 7 Fig 1. Necrotizing bronchiolitis with large numbers of neutrophilis in the lumen. Note CAV-2 intranuclear inclusion bodies in the bronchiolar cells (arrow head). Also note intracytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusion bodies typical of CDV (arrows). HE bar 100µm. Inset: Canine distemper virus antigen in epithelial cells cell, Avidin-biotin peroxidase reaction. 8 Fig 2. Necrotizing bronchiolitis with neutrophilic exudation. Note large intranuclear inclusion bodies in the bronchiolar epithelium (arrows). HE bar 100µm. Left Inset: CAV-2 antigen positive reaction in bronchiolar cell, Avidin-biotin peroxidase reaction. Right inset: Paracrystalline arrays of electrondense particles (50 ± 2.0 nm in diameter). 9