The Contexts of Dialogue: Three Perspectives

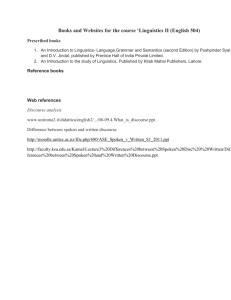

advertisement