Appendix 3

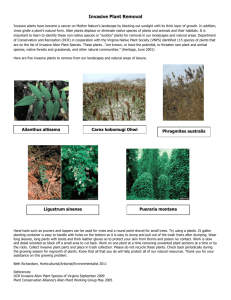

advertisement