Complex Predicates involving Events, Time and Aspect: Is this why

advertisement

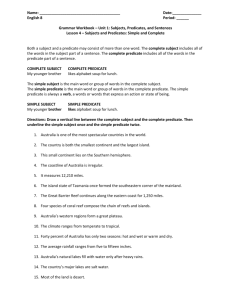

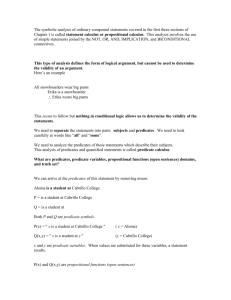

Complex Predicates involving Events, Time and Aspect: Is this why sign languages look so similar? Ronnie B. Wilbur Purdue University, W. Lafayette, IN 47907 USA Introduction This paper will address the motivated mapping between the (formal) semantic components of events and their overt morphophonological representations in ASL. ‘Complex predicates’ here means any non-nominal predicate that consists of at least a Verb (including change-of-state adjectives, Klima & Bellugi 1979). Other potential components of a complex predicate include: telic/atelic event structure; duration of an event; completion of an event; elapsed time between events; temporal aspects of events (e.g. habitual, iterative); and arguments and their collectivity/distributivity. There are 3 main claims that I will support with respect to predicate sign formation: a. Events: The morphophonology of predicate sign formation reflects Pustejovsky (1995)’s 3 types of events, States, Processes, and Transitions, and their arguments. b. Aspects: Aspectually modified forms (Resultative, Incessant, Continuative, etc) are compositional (each piece contributes meaning) rather than templatic (a set of features is applied to the root/stem, as suggested in Klima and Bellugi 1979). c. Grounding: Physics and geometry are recruited to provide formational material for the representations of the semantic components of these event structures. Claims and Data a. Events and Signs An event structure model permits a general statement of the semantic-morphologicalphonological relationships needed. Following Pustejovsky (1992: 56), a State is “a single ongoing event (e) that is evaluated relative to no other event.” A Process (P) is “a sequence of events identifying the same semantic expression”, which can be “divided at any point into an event that is just like the undivided event” (e.g. run, sleep). A Transition (T) is “an event identifying a semantic expression, which is evaluated relative to its opposition,” and therefore has a distinct final state en, which by definition makes these events telic. Prior to the final state, there is either another State (punctual change of state) or a Process (non-punctual). In ASL, Transition predicates have phonologically distinct end-States in their form. To qualify, the phonological features associated with the second timing x-slot (Brentari 1998) of a sign (the end-State) cannot be the same as the first x-slot (initial State). Examples include change of handshape (THROW, UNDERSTAND), change of orientation (DIE), and change of location (ARRIVE). The points (absence of movement) associated with timing x-slots refer to set-theoretic individuals (x), be they initial or end States, event start and stop times, the event arguments, or other set elements. In contrast, atelic States and Processes only have their initial x-slots specified; these specifications then spread to any subsequent x-slots. They may have no movement, or tremored movement [TM], which is a morpheme referring to the ‘passage of time without event change’ (SICK), or ‘tracing’ movement. In sum, the sign formation correlates directly with type of event, telicity of event, and number of arguments. Furthermore, all non-punctual predicate signs have path movement. My claim is that, with the principled exception of classifier predicates and ‘tracing’ movements (which I will address), this path movement indicates elapsed time (t) of an event and that path movement between aspectual reduplications reflects elapsed time between events. b. Aspects I claim further that all temporal aspectual modifications of predicate signs (Durative, Resultative, Continuative, Incessant, Iterative, Habitual, Completion) and spatial modifications (distributive, collective plural) are also compositional. These complex forms can be interpreted from the component pieces, including reduplication. To do this, path needs to be divided into straight (default) and curved. Curved lines show elongated time. (Change of speed is also phonological but not discussed here further.) When there is (default short) time between telic events, there is a clear return from final position of one event to initial position of next event, that is, a short linear return path, creating the Habitual. For the Incessant, where there is essentially no time between events, there is a rapid sequence of like event movements in which you cannot tell where one discrete event ends and the next begins. For the Iterative, the time between events is significantly long (for the context), and the return path is curved while the event path is not. Completive is shown when the target end-State (e.g. change of handshape, orientation) is reached; Incomplete when it is not. For argument information, the phonological specification is (the movement stopping at) a specified point (p). Each such stop is an individual, resulting in singular, dual, or individuated distributive (minimum of three points). The plural arc (Fischer 1972) indicates collective. This same system underlies overt verb agreement. Consider the complex predicate ‘Distributive embedded in Iterative [[give + distrib] + iterative]’ (Klima & Bellugi 1979). Phonologically, the default (short) path movement of GIVE stops at e.g. three sequential arbitrary points (because there are no indexed antecedents) for Distributive. The time between events is then affixed: a curved path in a plane perpendicular to the movement of the event. The shape of the path movement for time between events (straight or curved) and the presence of [repeat] is specified by the temporal aspect Iterative, which is syntactically higher than ‘verb + distrib’. Classifier predicates and those with ‘tracing’ movement do not participate in this predicate system because their path movements are already specified as meaning spatial path, extent, or shape outline. These paths are not available to be metaphorically interpreted as ‘elapsed time.’ That is, length of the path movement does not map to length of the event. c. Grounding (Iconicity) To construct these forms, ASL uses geometric options of points and lines (straight, curved) or of tracing a figure, and the marked physical options of distance (with distinctions of large, small), duration (long, short) and velocity (fast, slow) in addition to whatever is considered to be the default neutral values (which are context, sign, and signer dependent, e.g. normal conversation, urgency). Given that these physical options and limitations are, so far, universal, it is expected that sign languages will recruit these options and assign them various meaningful functions. In fact, this generalization may provide the fundamental similarity that makes sign languages look more similar to each other than spoken languages do (Newport and Supalla 2000). It is an empirical question whether the functions that they are recruited to perform are similarly universal or vary widely. Currently, data is being collected on Austrian Sign Language to address this question.