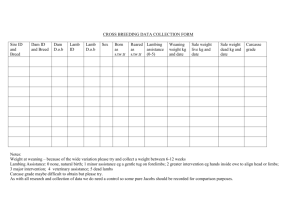

Economic evaluation of lamb production RD&E investment 1990/91

advertisement