Reconciliation after genocide, mass killing or intractable conflict

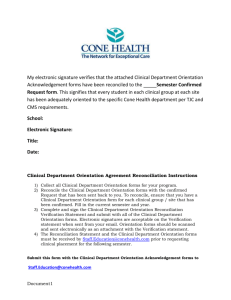

advertisement