Developing a Quality-Adjusted Output Measure for the Scottish

advertisement

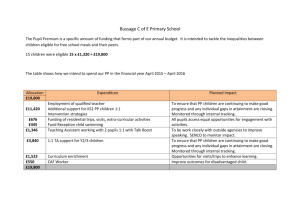

DEVELOPING A QUALITY-ADJUSTED OUTPUT MEASURE FOR THE SCOTTISH EDUCATION SYSTEM1 GSS METHODOLOGY CONFERENCE - 23 JUNE 2008 JOANNE BRIGGS - SCOTTISH GOVERNMENT 1. INTRODUCTION This paper provides a summary of the work undertaken to develop a new quality-adjusted output measure for the school education system2 in Scotland. Responsibility for education is devolved to the constituent parts of the United Kingdom: England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland and there are differences between the four systems. The new measure for Scotland was incorporated into the Scottish Government's quarterly GDP series in 2007. 2. BACKGROUND The UK National Accounts measures the output (in terms of GDP) from the private and public sectors within our economy. Public sector output accounts for a sizable proportion of GDP, and therefore it is important that it is measured as accurately as possible. However, measuring the output of public services is extremely difficult as these tend to be services which do not attract a market price. Atkinson Review The Atkinson Review, published in January 20053, was an independent review looking at the measurement of government output and productivity. It outlined a number of recommendations for improving the way the output from public services is recorded in the UK National Accounts. The main recommendations for education included: Measuring Pupil Numbers: it was agreed that the number of pupils taught was a reasonable representation of the quantity dimension of schools output. However, it highlighted that the measure should take account of variations over time in absence in order to accurately reflect the number of pupils actually taught. Measuring the Quality of Education Output: new methods for measuring the quality of education output should be investigated. Coverage: the new measure for education output should take full account of results from throughout the UK. These recommendations formed the basis of our programme of work to develop a new output measure for the Scottish education system. 1 This paper was originally developed for an OECD workshop on Measuring Education and Health Volume in June 2007 and has subsequently been updated with more recent data. 2 This includes publicly funded primary and secondary schools. 3 http://www.statistics.gov.uk/about/data/methodology/specific/PublicSector/atkinson/final_report.asp 1 Education system in Scotland School education in Scotland is compulsory from age 5 to 16, although almost all four yearolds and most 3 year-olds attend nursery classes prior to this. Primary education is a sevenyear programme (P1 to P7). Secondary education is a six-year programme (S1 to S6), the first four years of which are compulsory and enrol children aged on average between 12 and 15. Around three quarters of young people stay on for S5 and 44 per cent continue to S6. S5 and S6 are mainly delivered in secondary schools (though colleges do offer such courses as well). Both primary and secondary schools are comprehensive establishments built and staffed by Scotland's 32 local authorities. There are no formal examinations in Scotland prior to those taken at the end of S4 (i.e. there is no equivalent to the Key Stages in England). Instead, schools judge the progress pupils are making throughout their schooling. This information was previously collected centrally but is now only used at local authority level. Instead, the Scottish Government introduced the Scottish Survey of Achievement4 which uses a sample of pupils from a number of authorities to gauge pupil progress throughout school. In the final two years of compulsory schooling (S3/S4), students prepare for examinations, generally Standard Grades. During S5 most pupils tend to take a combination of Highers and Intermediate qualifications, whereas in S6 the majority of those staying on will predominantly sit additional Highers and Advanced Higher qualifications. 3. DERIVING A QUALITY-ADJUSTED OUTPUT MEASURE Previous methodology The approach previously adopted for measuring education output in the Scottish quarterly GDP series was an input-based method where staff employed was used to measure education output. The main criticism of this measure of the output of education was that it was entirely inputsbased and therefore it was not possible to gauge the changes in productivity of educational service delivery. For example, education output would be boosted by simply employing more teachers. This fails to take into account the actual volume of pupils taught and the level of education received. Approach to new measure The Atkinson Review highlighted that education output should include the volume of education (measured by pupil numbers adjusted by attendance rate) and a quality measure. In terms of the volume measure, this is a straightforward calculation. The volume index for education output has experienced a decline in recent years as a result of a fall in pupil numbers (9 per cent fall over the last ten years). Although the attendance rate has improved slightly, this has not been enough to outweigh the decline in pupil numbers. However, developing a quality measure to adjust the volume of education output is more difficult because of a number of complicating issues. Before investigating these issues and possible methods for measuring quality, it is worth examining why we should adjust education output to take account of changes in quality. 4 http://www.ltscotland.org.uk/assess/of/ssa/index.asp 2 Rationale for Adjusting for Quality If we do not adjust for changes in the quality of the education system, then output will simply be driven by the number of pupils attending school. This volume-based measure of output fails to take into account the quality of education received. In theory, the quality of education received could be measured by the quality of teaching in the education system. However, in practice it is very difficult to assess the quality of teaching a pupil receives. Given such difficulty, attainment is often used as a proxy (i.e. assumes that “high” quality teaching will have a larger impact on pupil attainment than “low” quality teaching). Although attainment is a useful proxy for such changes in the quality of education received, it is important to recognise that there are some drawbacks to this approach. Principally, it fails to recognise the wider benefits pupils receive from the education system. Like indicators on the quality of teaching, it is very difficult to obtain robust time-series data on wider benefits. Measuring attainment Given that we accepted the general principle that attainment provides the most suitable proxy for measuring the quality of education, we need to decide what levels of attainment to be captured. There are a range of methods available to do this5. Single Threshold Measure A threshold measure could be used to account for the changes in the quality of Education output over time - this involves tracking the proportion of students reaching a certain threshold. The then Department for Education and Skills suggested using GCSE results for England and Wales; for Scotland an equivalent qualification would be Standard Grades. There are three distinct levels of Standard Grade award – Credit, General and Foundation – with Credit level covering the top two of seven grades; a threshold measure could therefore be based on the proportion of pupils achieving 5+ awards at Credit. However, this fails to recognise changes in attainment at Highers and Advanced Highers which are usually gained during S5 and S6. Consequently, a single threshold measure would not recognise changes in the quality of output for the final two years of the Scottish school education system. Average Tariff Score Method A quality-adjustment could be developed based on the Average Points Score (APS) of Standard Grade candidates in each year - this involves converting exam grades into points. However, there are concerns that this method would not reflect the true changes in quality of output over time due to the non-linear nature of APS in Scotland. For example, greater weight is given to improvements at the higher end of the attainment spectrum than the lower. Cohort Progress Output Method This approach would track changes in pupil performance throughout their schooling. Whilst key stage test scores could in time allow this type of measure to be used in England, we are unable to use this approach in Scotland as there are no standardised tests for children before Standard Grades. 5 Measures of attainment were explored in a DfES paper - Measuring Government Education Output in the National Accounts http://www.dfes.gov.uk/research/data/uploadfiles/RW45.pdf 3 Combined threshold approach We think it is appropriate that the measure reflects changes in attainment at a variety of levels so that we fully capture improvements across the entire attainment spectrum of the education system in Scotland. Hence a combined threshold approach was chosen, which captures the entire attainment spectrum, including all the qualifications gained over the final three years of school (i.e. by the time the pupil leaves school at the end of S6). Differentiating Output by Attainment We classified the range of levels of attainment received into three categories: Category 1 represents the highest levels of qualifications gained; Category 2 represents the middle level of attainment; and Category 3 represents attainment at the low end of the attainment spectrum. Chart 1 illustrates the proportion of pupils gaining qualifications in these categories. Chart 1: Proportion of Pupils Gaining Qualifications, by Attainment Category Proportion of Pupils Gaining Qualifications 60.0 50.0 40.0 30.0 20.0 10.0 0.0 1999 2000 2001 Category 1 2002 2003 Category 2 2004 2005 2006 Category 3 Over the past eight years there has been a movement from the lowest level of attainment (Category 3) to the medium level of attainment (Category 2). At the same time, the proportion of pupils gaining the highest level of attainment, Category 1, has remained fairly stable at around 30 per cent. Weighting the Different Levels of Attainment Measuring quality-adjusted output requires each category of attainment to be given a weight which reflects its contribution to the total. Applications of this approach have traditionally used weights which reflect the cost of producing each category of output. However, in this case there is evidence that the benefits of the education received would not necessarily be reflected by using cost weights. Instead, we decided to base the weights on the expected future earnings a pupil can expect to receive as a result of gaining a particular level of attainment. This expected future wage is 4 calculated by multiplying the average earnings for each level of attainment by the associated rate of employment. This is highlighted in Table 1. Table 1: Expected Weekly Wage in Real Terms by Highest Qualification Gained6 Category 1 Average Earnings Employment Rate Expected Earnings Category 2 Average Earnings Employment Rate Expected Earnings Category 3 Average Earnings Employment Rate Expected Earnings 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 £275 0.75 £283 0.77 £304 0.78 £298 0.76 £290 0.77 £297 0.77 £308 0.79 £206 £218 £238 £226 £223 £229 £242 £211 0.72 £209 0.70 £230 0.70 £202 0.71 £229 0.72 £206 0.72 £212 0.70 £151 £145 £162 £143 £164 £149 £149 £176 0.47 £196 0.48 £203 0.49 £201 0.50 £188 0.50 £209 0.51 £210 0.50 £83 £93 £99 £100 £94 £107 £104 Averag e Weight 48 32 20 As we might have expected, there is a positive relationship between the expected future earnings of an individual and the level of qualification gained at school. Therefore the average weight for the different categories give greater importance to more difficult qualifications gained. It is important to note that we are not attributing the “credit” of future earnings to the education system, but instead are using expected future earnings as a way of weighting the relative importance of each level of attainment gained in school. Quality-Adjusted Output Index for Education In order to produce an output index for education which is adjusted for quality, we take the total number of pupils in the final year of secondary education, differentiate them by the level of attainment they have achieved over the final three years of education, and then weight them according to the relative importance of each category. This weighted total is then converted into an index which tracks the change in output over time. The calculation is illustrated in Table 2. Table 2: Quality-Adjusted Output Index for Final Year of Secondary Education Number of Pupils Category 1 Category 2 Category 3 Total Number of Pupils in Cohort 6 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 18,189 9,557 31,014 17,899 8,920 29,358 18,769 9,619 28,388 18,486 10,191 28,203 18,583 11,005 28,024 18,479 11,100 28,079 18,494 11,414 28,870 18,315 11,666 28,531 61,659 59,071 58,652 59,250 60,138 59,998 61,035 60,446 Data is collected from the annual Labour Force Survey - a sample of around 23,000 households in Scotland. 5 Weighted Total Output Index 18046 94 99.8 17366 36 96.0 17805 85 98.4 17816 68 98.5 18086 68 100.0 18078 92 100.0 18347 56 101.4 18274 49 101.0 This output index tracks the change in growth which can be caused by changes in the number of pupils attending school and changes in the proportion of pupils who fall into each attainment category. If these proportions remain constant throughout the period in question, there will be no change in quality and therefore output growth will solely be driven by changes in pupil attendance. If the proportions in each attainment category vary from year to year, then this will represent a change in the quality of education and will therefore influence overall output growth. This index represents the quality-adjusted output for the final year of pupils in secondary education. However, it fails to capture the output from the other 11 years of school education received in Scotland. One way to address this is to apply the differentiated output from the final year of pupils across each year group in order to more accurately reflect the total output from the school education system. By doing this, we are saying that the quality of education received in the final years of education (measured by level of attainment), is representative of the quality of education received throughout the school system. This is a realistic assumption as you would not expect significant differences in the quality of education received across the different stages of education (as often it will be the same teacher delivering certain subjects). By applying the proportion of pupils gaining each level of attainment to all pupils in primary and secondary education, and then weighting by the relative importance of attainment, we can produce an overall output index for the whole school education system. This is highlighted in Table 3: Table 3: Quality-Adjusted Output Index for Scottish Education System Number of Pupils Category 1 Category 2 Category 3 Total Number of Pupils Weighted Total (000s) Output Index 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 204,13 6 107,25 8 348,06 9 691,98 5 209,47 3 104,39 1 343,59 0 691,32 9 218,87 4 112,17 3 331,04 6 683,98 0 212,31 8 117,04 7 323,92 1 680,50 7 208,53 4 123,50 1 314,48 8 674,86 7 207,60 9 124,70 0 315,45 8 674,05 6 201,52 2 124,37 2 314,58 7 665,09 0 198,85 2 126,66 2 309,76 3 656,26 6 20,254 20,324 20,765 20,463 20,297 20,311 19,993 19,841 99.8 100.1 102.3 100.8 100.0 100.1 98.5 97.8 The calculation of the quality-adjusted output index captures all pupils attending school and adjusts by the quality of education received (measured by attainment). For those pupils who do not gain any formal qualifications from school, they will not be captured within the three attainment categories and therefore will not have a positive influence on the quality adjustment. This is because we believe it is inappropriate to claim pupils who fail to gain any qualifications have received a high quality education. However, they will still be captured in the quantity dimension of the output index. 6 The index is shown in Chart 2 below, with quality and quantity also shown separately. It is clear that the volume index has been driving done the overall output index, while quality has remained fairly stable. Chart 2: Quality Adjusted Output Index 103 102 101 100 99 98 97 96 95 94 1999 2000 2001 Quality 2002 2003 Quantity 2004 2005 2006 Quality-adjusted Output Triangulation and Sensitivity analysis The Atkinson Review highlighted the important role of triangulation when changing the methodology for measuring Government output. Broadly, triangulation has two key aims: To help supplement the existing evidence provided by the new methodology and to identify whether it supports or contradicts the new estimate of implied productivity. To help users understand the productivity figures by providing additional information to give a wider picture of the productivity of education services which has not been shown in compiling the education productivity figures themselves. Our triangulation analysis looked at evidence from Her Majesty's Inspectors of Education, international studies of educational achievement and the Scottish Household Survey. The evidence has provided support for the new measure. Additionally sensitivity analysis was conducted, for example examining different combinations of qualifications. This analysis led to very little impact on the results, again providing evidence of the robustness of the measure. 4. LIMITATIONS OF THE QUALITY MEASURE As highlighted earlier in the paper, there are many problems with trying to measure the quality of education received. Although attainment-based methods are often used as a proxy, they still have a number of limitations. 7 Firstly, they do not fully capture the wider benefits of education such as life-skills which are not reflected in attainment results. Furthermore, the attainment based approach does not capture changes in quality for that specific year of education, but rather reflects the accumulated impact of the 11 or more years of education a pupil receives. Consequently, there will be a time lag between when a new policy is introduced and when it will feed through to impacting the quality of education. One area for possible further work is on the weightings for the different categories of attainment. At the moment it is likely we are being slightly conservative in the weightings for Category 1. For example, the expected future earnings are based on the highest level of qualification gained. A high proportion of pupils in this category will go on to university and gain higher expected future earnings, however at the moment this is not captured in the weightings. It is unclear whether we should attribute some of the “credit” for these additional earnings to the school education system. 5. SUMMARY The Atkinson Review outlined the importance of developing a new quality-adjusted output measure for education. We have taken forward this recommendation and produced a proposed new output measure for the Scottish education system. The majority of the work undertaken has been investigating possible ways of measuring the quality of education received. We concluded that an attainment-based approach would be the most appropriate proxy for tracking changes in quality. The quality-adjusted output index was developed which captures changes in a wide spectrum of attainment, which is weighted by the expected future earnings associated with each level of attainment. Overall, the new output index for the Scottish education system has declined slightly in recent years. This has been driven by the fall in pupil numbers which has more than offset the positive impact of improvements in the quality of education received. 8