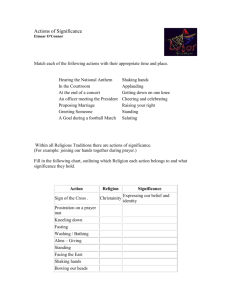

Public Admin Dictionary

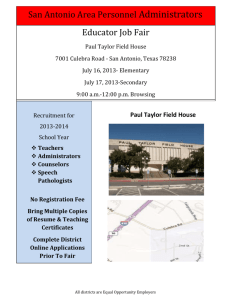

advertisement