Chapter 11: Conclusions About Asian Market Capitalism

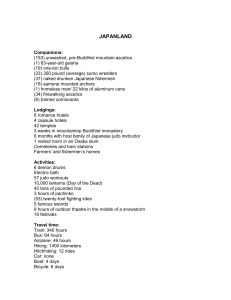

advertisement

1 Chapter 11 Conclusions about Asian Market Capitalism (revised 2009) The Japanese economy is definitely a capitalist, market economy. Most of the capital goods are owned by private individuals. Indeed, most property is private property. Government ownership is relatively small (and has become smaller in recent years). And markets are definitely the dominant economic institution. Yet this has been a different kind of market capitalism from that found in the United States or Europe. Because the economic system is relatively similar in Korea and Taiwan, we will call this “Asian Market Capitalism”. It stands in contrast to Liberal Market Capitalism in that it imposes greater constraints on withdrawal from business relationships but has more channels for negotiations within these relationships. Japanese companies will not abandon their workers, their banks, or their suppliers. However, they will commonly renegotiate the terms of their relationships with them. As we saw, Asian Market Capitalism also stands in contrast to the Social Market Economy. 1. Production under Asian Market Capitalism First, in Asian Market Capitalism, there is a high degree of competition between privately-owned companies. But this competition has been constrained by both government actions and by the horizontal and vertical groups (keiretsu). The Japanese have not accepted the idea of laissez faire. Instead, they believed that free markets would not provide a satisfactory rate of economic growth. Therefore, the Japanese government intervened significantly in the affairs of Japanese companies --- usually to aid them rather than to restrict them. Most importantly, the Japanese government intervened to shape the nature of the competition between the privately-owned companies. This intervention typically involved the participation and the consent of the businesses. It was called government “industrial policy”, and was described in Chapter 10. Industrial policy in Japan was much more extensive than that practiced in Europe (and was practically non-existent in the United States). Some people portrayed it as “Japan Inc.” And the Japanese did not accept the idea of the “invisible hand”. The constraints on competition provided by the keiretsu relationships, as described in Chapter 9, were unique to the Asian countries (although the relationships with the banks were similar to those of some European countries). Market economies have been dichotomized as either favoring competition or favoring cooperation. The Japanese economy would lean more in the direction of favoring cooperation than would the American economy. In recent years, there has been a shift in Japan in the direction of favoring competition. Cross shareholding in Japan has become somewhat less significant over the past 15 years although it is still important. And foreigners own more Japanese companies than in the past. But on a competition – cooperation dichotomy, the Japanese companies are still more cooperative and less competitive than are American companies. Until 1990, these two constraints on competition (the role of government and the horizontal and vertical groups) contributed the Japanese economic success for several reasons. First, without the government support and the forced licensing of technologies, the Japanese companies would have had a very hard time getting to the point where they could become competitive at all. Second, without the protected domestic market and the relations within the horizontal keiretsu, the Japanese companies would not have been able to launch their export drive. The protected home market provided the profits to offset any losses that might be made on exported products. And the horizontal keiretsu reduced the risks of failure; through the General Trading Companies, they also provided assistance that could not have been gained elsewhere. Third, without the inter-corporate shareholdings (within the horizontal keiretsu), the Japanese companies could not have developed their focus on the long-run that so distinguishes them from American companies. And fourth, without the horizontal keiretsu and the government 2 “industrial policies”, the cost of capital would have been much higher. More importantly, the risk of investment in new types of capital goods would have been greater. The development of institutions to reduce the risks inherent in business investment spending is one main aspect of the uniquely Asian version of market capitalism. A second reason for the success of the Japanese economy was the flexibility in production. The vertical keiretsu facilitated that flexibility. As we saw in the last chapter, in the 1960s, many Japanese companies were spending greatly on business investment spending (that is, on new capital goods). As a result, the Japanese ability to produce expanded well beyond the Japanese ability to consume. Rather than let some companies fail, the Japanese launched an export drive. But they could not compete head-to-head with the American companies. Therefore, they focused their manufacturing on niches in the market not well served by the American companies (for example, small automobiles). As they gained entrance to the American market, they would then change their products and move up to more profitable items. This meant that their strategy was based on product differentiation and on rapid change of products. To be able to pursue this strategy, the Japanese companies had to develop manufacturing systems based on flexibility. One aspect of this “Japanese system” of manufacturing involved a unique set of relationships between the companies and their suppliers called vertical keiretsu. Until recent years, this institution was unique to the Asian countries. Now the institution is common among European and American companies; today it is called a “supply chain”. These vertical keiretsu, as described in Chapter 9, not only contributed to flexibility in production but also facilitated continuous innovation. They were a major reason that the Japanese system of inventory control (Just-in-Time) could be developed by Toyota. And they were a major reason that the Japanese emphasis on quality control could be as successful as it has been. Because of the vertical keiretsu, Japanese manufacturing plants could be smaller than similar American plants, helping to keep costs of production lower. Market economies have been dichotomized as relational trading or impersonal spot market trading. The Japanese economy leans more in the direction of relational trading than would the American economy. A third aspect of the “Japanese system” of manufacturing involved the very important role for small companies. Small companies are much more extensive in Japan than in the United States or Europe. Whether part of the vertical keiretsu or not, these small companies have been major contributors to the flexibility of production and to the high rates of innovation. They are also a major reason for the low rates of unemployment in Japan and for its wage flexibility. Small firms are promoted and protected in Japan to an extent far greater than found in other capitalist countries. According to at least one author, the role of small firms is THE major reason for the Japanese economic “miracle” --- not the role of the government or the role of the market. 3. Labor Relations under Asian Market Capitalism Asian Market Capitalism involves a unique system of labor relations. Unlike many American companies, large Japanese companies do not rely on unskilled labor or on a “reserve army of the unemployed”. Japanese factories are not as authoritarian as American factories, nor are the social differences (or wage differences) between management and the workers as great. Workers are more generally trained (trained to do many tasks); this complements the orientation toward flexibility in production. Because they are more generally trained, Japanese blue collar workers are paid in a manner similar to white collar workers in the United States and Europe. Workers (at least male workers) are economically secure to age 60. Companies have been dichotomized as “employee favoring” or “shareholder favoring”. In this dichotomy, Japanese companies lean to the “employee favoring” side (as do European companies) while American companies lean to the “shareholder favoring” side. 3 This job security is similar to that found in several European countries. It has many ramifications. First, it means that there are high costs to workers if they quit their jobs. Knowing that workers are very unlikely to quit is a necessary condition for the companies to be willing to provide general training (training that involves skills useful in many jobs). If workers could quit easily, as they can in the United States, companies would be unlikely to pay for the general training as any skills learned by the workers could then be taken to another employer. Second, knowing that workers are very unlikely to quit allows the companies to get away with granting wage increases that are lower than productivity increases (and to reduce wages when company performance is poor). This wage flexibility is one of the keys to the relatively low unemployment rate in Japan. Third, job security obviously satisfies an important desire of the workers. Loyalty, both from the workers and from the companies, is valued much more in Japan than in the United States. A Japanese executive gets as much pride and esteem from maintaining employment during tough times as an American executive would get from maintaining the company’s profits under similar circumstances. Without “permanent employment”, general training, and wage flexibility, it would not have been possible for the Japanese companies to develop the system of flexible production that was a key to their success. Labor unions are also different in Japan than in the United States or Europe. The basic union in Japan is the enterprise union. It Europe and the United States, labor unions are more centralized. Compared to their counterparts in Europe, and even in the United States, Japanese enterprise unions appear to be very weak on all matters except dismissals. Being a union leader is seen as a stepping stone into management. Therefore, labor unions are not an independent force representing the workers. Japanese labor unions are not a main constituent of a political party that has achieved political power for any significant length of time. The contrast with Europe is compelling. On the other hand, Japanese companies have more worker participation in decisionmaking than is found in most American companies. Workers do not sit on Boards of Directors, as they do in some European countries. But they do participate in Joint LaborManagement Consultation and in Quality Circles – thereby influencing the manner by which production is organized. Worker participation in most American companies is limited to collective bargaining and to grievance procedures. 3. Equality under Asian Market Capitalism Despite the relative weakness of workers, Asian Market Capitalism has had considerable equality in the distributions of income and wealth. Indeed, Asian countries have been the most equal distributions in the world. In this regard, they resembled the Social Market Economies of Europe and contrasted with the Liberal Market Economy of the United States and Great Britain. They demonstrated that relative economic equality and economic success can go hand-in-hand. Indeed, it was argued that by enhancing social solidarity, economic equality may have contributed to economic success. CEOs in Japan earned 10 times the pay of their hourly workers in 2000 compared to 419 times for American CEOs. However, as Japan has changed to become more like a liberal market capitalist economy, inequality has increased. There is a smaller Welfare State in Japan than is found in most other industrial countries. While government spending is about the same percent of GDP as it is in the United States, it is well below the percent found in Europe or Canada. Especially noticeable is the poor provision for retirement in Japan. Workers over 60 are much more likely to be in the labor force in Japan than are workers in the United States or Europe. And they are forced to work in jobs that 4 pay relatively little. Elderly people are more likely to be considered a responsibility of their families in Japan than in the United States or Europe. And although the Japanese health care system has improved, the Japanese government still spends a lower percent of GDP on health care than the United States or European governments. In Japan, public assistance programs cover a very small portion of the population. And unemployment benefits last for only a short time. While overall spending on education is about the same in Japan as in the West, much more of that education spending is done by families than would be found in the United States or Europe. Inadequate provision of roads and public parks in Japan is well documented. Japanese companies often pay for places for recreation activities that are provided by the government in the United States. The Welfare State, a major component of the Social Market Capitalist Economy, is quite lacking in Japan. 4. Social Conditions under Asian Market Capitalism As with laissez faire, Asian Market Capitalism has not accepted the idea of consumer sovereignty. Consumers seem to have benefited least from the tremendous economic growth in Japan. As we saw, a higher portion of household income must be allocated to the purchase of food in Japan than in the United States or Europe. The homes are small by American standards and many lack the amenities found in typical American or European homes. Ownership of automobiles per 1,000 people is less than half that found in the United States. The insufficient provision of housing, education, and inadequate financial markets has forced the people to save a large amount of money. On the other hand, social conditions in Japan are in some ways superior to the United States or Europe. Crime rates are low. The rate of traffic accidents is also low. And pollution has declined to quite low levels for an industrialized country. Japan is a very healthy society. Life expectancy at birth is the longest in the world for both men and women. Japan rejects the liberal market economy notion of individualism. As we saw in Chapter 2, one main value of the liberal market capitalist economy is the central importance of the individual and the competitive struggle between individuals for economic success. In Japan, the group is of more significance than the individual. Loyalty to the group is one of the highest values. Instead of a competitive struggle for economic success, a Japanese economic organization is seen more as analogous to a family. 5. Trade under Asian Market Capitalism Asian Market Capitalism has not accepted the notion of free trade based on comparative advantage. Instead, as we saw, the Japanese government intervened greatly in order to change Japan’s comparative advantage in favor of heavy industrial goods. Japan’s market was closed for products that the government has desired to promote. In recent years, the Japanese market has opened considerably. Some people believe that it is as open as is the American market. Other people believe that the Japanese market is still closed in certain areas considered to be important and that the Japanese government is still intervening to provide Japan a competitive advantage in those areas. 6. Conclusion There was a time when Asian Market Capitalism seemed to be the panacea. Economic power was moving west, it was argued, from Europe to the United States and then to Japan. Some Americans argued that they needed to copy the model provided by Japan. And to some extent, Americans did. Meeting the challenge of competition from Japanese companies required changes in American and European methods of production. These changes finally came in the decade of 5 the 1990s. “Supply chains” (America’s name for the vertical keiretsu) have become common. So when you buy a shirt at Wal-Mart today, another shirt immediately replaces it in the store and an order goes into effect to produce another of the same shirt. However, since the 1990s, the American economy has generally performed well while the Japanese economy has performed poorly. One sees no talk of Japan as a model to be emulated at the present time. In this chapter, we have dichotomized economic systems on the following four scales: Employee Favoring Companies __________________Stockholder Favoring Companies Relational Trading ____________________________ Impersonal Spot Market Trading Cooperation Between Competitors _______________ Competition Between Competitors Strong Government __________________________ Limited Government On each of these four scales, Japan would be farther to the left side than would the United States or Great Britain, even today. The Japanese economy may be at a crossroads. Much has changed since the end of World War II. The consensus on the priority of economic growth is gone. A new generation has new and different goals. This new generation may be less tolerant of the inadequate housing, the poor provision of public goods (roads, parks, and so forth), the stresses and difficulties of the work life, and the expensive education. The Japanese population is aging rapidly. This will have to lead to major changes in retirement policies and in the social security system. It will also place great stress on the system of “permanent employment”. Japanese companies still face some hostility from American and European policy makers. Included in this is pressure for Japan to assume a place in the world commensurate with the size of its economy. This would mean paying more for its defense burden, giving more in foreign aid, helping to relieve Third World debt problems, and so on. It is the theme of Chapters 8 through 11 that Japan succeeded because its type of production was well adapted to the world economy that emerged in the 1970s and 1980s. The world economy changed again in the 1990s and will change yet again in the 21st century. Japanese companies are now more oriented to financial return and less oriented to increasing market share than was true prior to 1990. The system today is somewhat different from the system that existed in 1960. How the Japanese economy will change in the future and how these changes can be brought about are important questions that still await an answer. Let us conclude by re-examining the goals by which an economic system is to be evaluated discussed in Chapter 1. 1. Economic Growth Rate: As we saw, the economic growth rate of Japan was very high until 1990. Indeed, it was one of the highest in world history for a period as long as 40 years. Korea and Taiwan (not considered in this chapter but, in many ways similar to Japan) also experienced high growth rates. However, since 1990, the economic growth rate of Japan has been very low. 2. Standard of Living: The standard of living in Japan is very high. However, as mentioned above, consumers seem to have benefited least form the great economic growth rates. Many consumer amenities are deficient by Western standards. And provision of goods typically provided by the government has also been deficient. 3. Allocative Efficiency: Because of the numerous instances of government involvement in the economy and because of the lack of competition in some areas, Japan is less likely to meet the goal of allocative efficiency, as we defined it, than the United States. 6 4. Static and Dynamic Technical Efficiency: As we saw in the section on production, Japanese companies have been very good at finding ways to keep costs of production low and then to make them even lower over time. This is one of the strengths of their system. 5. Equity. Japan (and the other Asian countries) has experienced considerable equality in the distributions of income and wealth. The social gap between people at the top of hierarchies and people at the bottom is smaller than in most western countries. However, inequality has been increasing in recent years. 6. Full Employment. Until 1990, Japan had done very well at maintaining low rates of unemployment. Since 1990, permanent employment has been maintained even though it has been harder and harder to do so. But while unemployment rates have been low, more and more people have been forced into temporary employment. 7. Economic Security. As we saw, welfare state provisions for economic security have been deficient in Japan. This has been especially true as regards retirement. Forced retirement comes relatively early in Japan. This is followed by work at lower wages for long periods. The problem of retirement is likely to become more severe as the population continues to age. 8. Price Stability: Japan has generally maintained low inflation rates. However, in the 1990s, Japan did experience a long period of deflation. This deflation caused problems that are as significant as those that can be caused by inflation. 9. Military Power. Japan, as well as most of Asia, is defended by the United States. There has been a push to get Japan to undertake more of its own defense. 10. Environmental Quality. Until the 1980s, Japan puts its entire attention to the goal of achieving economic growth. Since then, more emphasis has been placed on the environment. In pursuing the goal of a cleaner environment, Japan has done as well as the United States or the countries of Europe. 11. Freedom. Japanese people are generally free people. Theirs is a democracy, although only one political party has been dominant since 1955. Bureaucrats once had more power than is usually found in other democracies. But that has been changing, with more power going to elected leaders. According to the Index of Economic Freedom of the Heritage Foundation, Japan ranks 19th of the 179 countries ranked. (The United States ranks 6th and Great Britain ranks 10th.) Questions for Analysis 1. Name some ways by which the Japanese economy has shifted in the direction of a liberal market capitalist economy. Why do you believe this shift has taken place? 2. Name some ways by which the Japanese economy has NOT shifted in the direction of a liberal market capitalist economy. Why do you believe the Japanese have held on to so much of their Asian Market Capitalist system?