Downloads

advertisement

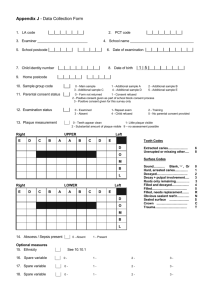

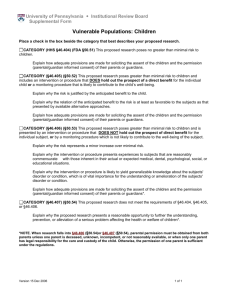

Does Parental Consent for Birth Control affect Underage Pregnancy Rates? The case of Texas November 2011 Preliminary version: comments are most welcome, but please do not cite without permission. Sourafel Girma School of Economics Sir Clive Granger Building Nottingham University University Park Nottingham NG7 2RD United Kingdom Tel: + 00 44 115 951 5482 Email: Sourafel.Girma@nottingham.ac.uk and David Paton* Nottingham University Business School Jubilee Campus Wollaton Road Nottingham NG8 1BB United Kingdom Tel: + 00 44 115 846 6601 Email: David.Paton@nottingham.ac.uk *Corresponding author Acknowledgements: We are very grateful to Janice Jackson at the Texas Department of State Health Services for her assistance with the birth and abortion data. We thank also participants at a staff seminar at the University of Surrey for useful comments. Does Parental Consent for Birth Control affect Underage Pregnancy Rates? The case of Texas Abstract In 2003, Texas became the second state to mandate parental consent for the provision of state-funded contraception to minors. Previous work based on conjectural responses of minors, predicted that the ruling would lead to a large increase in the Texas underage pregnancy rate. In this paper we examine the actual impact of the parental consent mandate on the under-18 pregnancy rate using both state- and county-level data and using 18-year olds as a control group. The county-level data allows us to use a statistical matching estimator to compare the effect of parental consent in counties with and without family planning clinics that are subject to the ruling. We control for both observable and unobservable characteristics that may be systematically correlated with the presence of affected clinics by combining difference-in-differences and difference-in-difference-in-differences strategies with propensity-score weighted regressions. The estimates provide little evidence that requiring parental consent for state-funded contraception led to an increase in the underage pregnancy rate. Keywords: propensity score weights; parental consent; family planning; teenage pregnancy; abortion. JEL Classifications: C21, I18, J13. 2 Does Parental Consent for Birth Control affect Underage Pregnancy Rates? The case of Texas 1. Introduction In this paper we use treatment effects evaluation estimators to test whether mandatory parental consent for the provision of state-funded birth control to minors leads to an increase in underage pregnancies. Policy discussions on the appropriate level of parental involvement in sexual health decisions of minors generate a huge amount of controversy. The underlying ethical debate rests on the balance between the rights of minors to make autonomous healthcare decisions and the rights of parents and carers to be involved in decisions affecting those for whom they have legal responsibility. In practice, policy arguments often hinge on the likely impact of mandatory parental involvement on the sexual health of minors and, in particular, rates of underage pregnancy. Legislation to mandate parental involvement for birth control in the U.S. has been considered recently both at the federal level and by numerous state legislatures. Other countries such as England, the Republic of Ireland and the Philippines are in the process of debating proposals either to abolish existing parental consent provisions for contraception or to put new ones in place. Despite the level of activity in the policy arena, the academic literature has paid very little attention indeed to this issue. This is in stark contrast to the considerable body of evidence, much of it conducted by economists, relating to parental involvement for abortion. In January 2003, Texas became the second U.S. jurisdiction to mandate parental consent for the provision of state-funded contraception to teenagers below the age of 18.1 Franzini et al (2004) use survey data on conjectural responses of teenagers to changes in confidentiality along with data on failure rates of contraception to estimate the likely effect of the Texas regulations. They projected that the law would lead to more than 5,000 additional births and 1,600 additional abortions per year amongst minors in the State. This implies an increase in the underage pregnancy (defined as abortions plus births) rate of about 20%, with an estimated direct medical cost of about $44 million. Whether or not these projections translate into actual additional pregnancies and costs depends on the actual, rather than behavioral, response of minors. To date no research has been undertaken to estimate the actual effect of the Texas parental consent law on pregnancy rates amongst minors and it is this gap which we are trying to fill in this paper. The results 1 Utah has had s similar restriction in place for a number of years. 3 are likely to be of interest not only to policymakers in Texas but also to those in other states and countries which may be considering the introduction of similar laws. Further, the results should provide insights into whether adolescents respond to new incentives induced by regulatory change in ways predicted by standard neo-classical models. The empirical approach taken in the paper is first to undertake some preliminary analysis to explore whether the parental consent law for family planning actually affected the take-up of contraception amongst adolescents. We then test for a state-wide effect of parental consent on pregnancy by comparing changes in rates amongst minors before and after the ruling relative to changes amongst older teenagers. Establishing a causal effect at the state level is potentially complicated by state-wide changes to minor pregnancy rates caused by other contemporaneous factors. For example, in September 2005, Texas strengthened its parental involvement law for abortions on minors, mandating parental consent rather than just notification. To control for such effects, we exploit the fact that parental consent for contraception is only required for state-funded, rather than federally-funded, contraception. That means that family planning clinics receiving funding under the (federal) Title X scheme, should be relatively unaffected by the ruling, whilst non-Title X funded clinics will be affected. By identifying those counties with such affected clinics, we are able to use statistical matching methods to help isolate any causal effect of the parental consent mandate. We are careful to control for both observable and unobservable characteristics that may be systematically correlated with the presence of affected (i.e. non-Title X) clinics. We do so by combining, difference-in-differences and difference-in-difference-in-differences strategies with propensity-score weighted regressions. 2. Parental Consent for contraception – the evidence to date Following the seminal work of Becker (1963), the economic literature has offered several theoretical models in which teenagers make decisions regarding sexual activity, contraceptive use and pregnancy resolution based on their subjective evaluation of expected costs and benefits of uncertain outcomes. Akerlof, Yellen and Katz (1996) and Paton (2002) argue that easier access to contraception may lower the perceived costs of underage or extra-marital sexual activity and, as a result, can have an ambiguous effect on unwanted pregnancy or abortion rates. Similar models have been presented in the context of sex education (Oettinger, 1999) and abortion (Levine, 2003, 2004). More recently, Arcidiacono, Khwaja and Ouyang (2011) develop an inter-temporal model in which “habit persistence” is a feature of teen sexual behavior. Once a relationship progresses to sexual intercourse, the authors 4 argue that it becomes harder for the couple to switch back to abstinence. The prediction, confirmed in their empirical analysis, is that more costly access to contraception leads to an increase in teen pregnancies in the short run, but to a decrease in the long run. In the context of such economic models, the predicted effects of a parental consent requirement for contraceptives on underage pregnancies are unclear. Such policies might discourage some young women from having sexual intercourse, which should lead to a reduction in pregnancies among minors. However, pregnancies could increase if some young women who would have used prescription contraceptives absent the parental consent policy have intercourse anyway but use less effective methods of birth control or no contraception at all. Pregnancies would not be affected if minors, who would have used prescription birth control absent the policy, either obtain parental consent after the policy change or, instead, manage to access supplies from other providers. A number of studies have used surveys to obtain conjectural responses from teenagers on their likely response to hypothetical parental involvement requirements. These studies suggest that parental consent laws might indeed affect both teens’ sexual activity and contraceptive use. In a survey conducted at Planned Parenthood clinics in Wisconsin, 59% of minors said they would discontinue use of contraceptive services if parental involvement were required (Reddy, Fleming and Swain, 2002). In surveys conducted at publicly funded family planning clinics across the U.S., 40% of young women said they would not go to publicly funded clinics that required parental consent for prescription birth control (Jones et al., 2005). Some minors said they would switch to condoms or other non-prescription forms of birth control. About 6% said they would continue to have intercourse but not use any contraceptives. About 7% said they would stop having intercourse, although only 1% indicated this as their only likely response. However, 60% of minors in one study (Jones et al., 2005) and 45% of teens in another (Harper et al., 2004) said a parent was already aware they obtained sexual health services at a clinic, suggesting that many minors might not change their behavior in response to a parental consent policy. The results of these conjectural responses form the basis for the predictions by Franzini et al (2004) that the parental control mandate in Texas would lead to a large increase in underage pregnancies. However, it is difficult to assess the actual effect of a parental involvement requirement from surveys about hypothetical policy changes. Indeed, previous studies of the impact of more general changes to availability of family planning to minors are at best inconclusive (Girma and Paton, 2006, 2011; Kearney and Levine, 2009; Raymond et al., 2007; Evans, Oates and Schwab, 1992). 5 In the first place, it may be that teen’s actual responses will be very different to the hypothetical responses declared to researchers. Second, the samples for such studies tend to be drawn from teens attending birth control clinics and who are likely already to be sexually active. The work by Arcidiacono et al (2011) suggests that the response may be very different amongst young people who are not yet sexually active but who will consider such a transition in the future. Very few studies have examined the actual impact of limitations on the confidentiality for contraception on pregnancy rates (rather than just on the uptake of services). Paton (2002) examines the impact of the Fraser ruling which meant that for most of 1985, family planning could not be provided to underage girls without parental involvement in England and Wales. Take-up at family planning clinics amongst this age group dropped by about 30% in 1985, yet the underage conception rate in England decreased slightly relative to the rate amongst older teenagers. Similarly, the rate also did not increase relative to the underage conception rate in Scotland where the Fraser ruling did not apply. A previous study of the imposition of parental consent for family planning in a single county (McHenry) in Illinois found that the requirement led to an increase in the percentage of births to women under age 19 living in McHenry County relative to three other nearby counties but not to an increase in the percentage of abortions or pregnancies occurring among teens (Zavodny, 2004; Zavodny, 2005). To date no studies at all have examined the impact of the parental involvement restrictions for family planning at a state-wide level. There does exist a much larger literature on the related issue of parental involvement for abortion. Methodological difficulties, such as controlling adequately for abortions carried out in neighboring states without such a law, make it hard to draw firm inferences from the data, but the majority of studies to date find that parental involvement laws have significant effects on teenage fertility and sexual behavior. For example, relative decreases in underage abortion rates are observed by New (2011), Joyce, Kaestner and Colman (2006) and Levine (2003) whilst the latter also concludes that these laws lead to reduction in total pregnancy rates amongst minors. Klick and Stratmann (2008) use rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) as a proxy for risky sexual activity and find that states implementing parental involvement laws experienced relative reductions in some STIs amongst minors. There is some evidence that parental involvement laws have differential effects for older and younger teenagers. For example, Colman, Joyce and Kaestner (2008) provide evidence that the 2000 law mandating parental notification before abortions on minors in Texas decreased both abortions and births amongst girls aged 17 at the time of the birth or abortion. However, 6 amongst a slightly older cohort (girls aged 17 at the time of conception) abortions decreased by a lower amount whilst births increased (albeit by a statistically insignificant amount). 3. Methodology 3.1 State-level Estimates Based on aggregate state level data, we employ logit regression for grouped data to determine the impacts of the parental consent mandate on underage pregnancy rates. We measure the impacts as changes from 2002 (the year before the mandate) to the three years after the mandate for two treatment groups: under-18s (U18) and under-16s (U18), relative to the 18 years olds (the control group).2 The Texas parental consent mandate applies to those aged under-18. There are several reasons for selecting the second treatment group (under-16s). In the first place, previous research (Colman et al, 2008) suggests that the impact of parental consent laws may differ between older and younger teens. One reason for this is that parental consent may be more strongly binding to younger teens who are less likely to be able to travel independently to access alternative sources. Further, policy makers tend to be relatively more concerned about pregnancies amongst younger teens than amongst those approaching the age of majority. Finally, some older minors (for example those that are married) are considered ‘emancipated’ in Texas state law and are exempt from the parental consent ruling. Since our estimation methodology involves “before” and “after” periods for the control and treatment groups, the relevant estimates can be interpreted as difference-indifferences estimates. The estimating equation in this analysis can be expressed as: (1) where p is the number of pregnancies (abortions plus births) divided by the population for the relevant age group at the estimated time of conception, i represents the three age groups; t=2002,….,2005, and Du16 and Du18 denote group dummies for under-16s and under-18s respectively. We repeat the analysis for the whole sample and for the sample of NonHispanic Whites, Non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics separately. Our results are robust to using more than one year for the “before” period. We also report results for each individual year of the “after” period. 2 7 3.2 County Level Estimates The availability of county-level data allows us to estimate the average treatment effect of the binary treatment, parental consent for family planning, on the scalar outcome variable, county-level pregnancy rate. Our identification strategy exploits the fact that parental consent for contraception is only required for state-funded, rather than federally-funded, contraception. That means that family planning clinics receiving funding under the Title X scheme, should be relatively unaffected by the ruling compared to non-Title X funded clinics. In our empirical model we are careful to control for two potential sources of bias: (i) unobservable characteristics that are correlated with both the treatment and outcome; and (ii) the possibility that assignment to the treatment is systematically correlated with observable pre-treatment characteristics, or the self-selection problem. Following the seminal contribution of Rosenbaum and Rubin (1983), one can remove estimation bias by using propensity score matching, where the propensity score is defined as the probability of assignment to the treatment conditional on pre-treatment characteristics, say Z. More recent work has shown that greater efficiency relative to propensity score matching can be obtained if one transforms the propensity score estimates into weights in the relevant regressions, the so-called the propensity score reweighted regression (Hirano et al, 2003 and Busso et al, 2009). In this approach, treatment observations receive a weight of whereas control observations receive a weight of , . It is worth noting that controlling for self-selection by adjusting for the propensity score would not remove all biases as long as there are unobservable characteristics affecting the potential outcomes and the decision to select into treatment. Fortunately, the influence of time-invariant unobservable characteristics can be controlled by using country-level fixed effects in the regressions, which is equivalent to using the difference-in-differences (DD) estimator in a two-period (pre- and post-treatment) panel data model. Hence our baseline econometric model consists of combining the DD approach with propensity score reweighted regression. The steps involved in this approach can be summarized as follows: (i) Estimate the propensity score via a probit model of the probability treatment in 2003 as a function of pre-treatment (2002) characteristics: . The characteristics used to obtain the propensity score are as follows: the percentage of the population living in poverty (poverty); the two-year lagged pregnancy rate (lag pregnancies); an indicator variable for whether or not the county is urban in nature (urban); an indicator variable for whether or not the county borders either Mexico or 8 another U.S. state (border); the proportion of the relevant population that are Hispanic (Hispanic); the proportion of the population that are Black (Black); the number of Title X (i.e. unaffected) clinics present in the county as of 2001 (Title X (2001)). Based on the estimated propensity scores, we only keep observations on the common support by deleting control observations whose propensity score is smaller (higher) than the minimum (maximum) propensity score of the treatment group. (ii) Denoting the outcome variable (under-18s/under-16s pregnancy rate) by y, we run the following propensity-score reweighted DD regressions separately for t=2003, 2004 and 2005: (2) In the above equation, the estimate of s is interpreted as the average treatment effect of Title-X clinic attendance in 2003 on pregnancy rate at time t. Refining the DD estimator A key identifying assumption of the DD estimator is the so-called same time-effect condition which stipulates that, while treated and untreated units may be systematically different in terms of the level of the response variable y, the trend in y would not have been different across units in the absence of treatment. The presence of differential trends in the outcome variable across treated and untreated counties can therefore bias the DD estimator. To guard against this possibility, we refined Equation (1) by using the more robust difference-in-difference-in-differences (DDD) strategy. Specifically, we calculate the change in outcome of the under-18s/under-16s in treatment adopting counties relative to that of the older cohort (18 year olds) in the same counties, and measure this relative to the equivalent change in the non-treatment counties. Cast in a regression framework, this translates into running the following propensity score reweighted regressions (3) Exploring heterogeneous treatment effects As noted earlier, the estimate of the s in the above regressions provides a consistent estimate of the average treatment effect. The approach we follow can easily be extended to explore the possibility that the treatment effects depend on pre-sample characteristics by interacting the treatment dummy with selected demeaned covariates (e.g. Wooldridge, 2002, chapter 18). Accordingly we also allow the treatment effects of Title-X clinic attendance to vary 9 according to the proportions of blacks and Hispanics in the county population of females aged 15-19. Denoting these demeaned proportions by X, Equation 2 can be modified as: (4) 4. Data and Descriptive Statistics The Texas Department of Health provided data on abortion and births by county of residence along with estimated gestational age, date of birth of mother. These data enabled us to estimate ages at conception for all Texas residents including those abortions taking place outof-state. As noted by Joyce et al (2006), the fact that the Texas abortion and birth datasets are available by year of and age at conception make them far superior to data from many other states which are only available according to the date of the actual abortion or birth. Having data by state of residence also gets around the problem that some residents will obtain abortions (or give birth) in other states. We construct rates of pregnancies for all those under the age of 18 and also for under-16s on the grounds that the impact of the change may be different for younger minors (see, e.g., Joyce et al, 2006). For our control group in the D-DD analysis, we use rates for 18 year olds and, as an alternative, 18 and 19 year olds together. County-level contraception data are from the Alan Guttmacher Institute (AGI) cliniclevel surveys that took place in 2001 and 2006. These provide data on the total number of clients and the number of teenage clients for each county broken down by Title X-funded clinics and other (non-Title X) clinics.3 A key issue which has affected many studies of parental consent for abortion is access to services out-of-state. As Joyce et al (2006) point out, this problem is likely to be less acute in the case of Texas due to the large geographical area which means accessing services outof-state is particularly difficult for many residents. We can imagine that the hassle cost of independent travel to access services without parental assistance is likely to be particularly high for minors. On the other hand, accessing out-of-state services is still likely to be an issue for those residents living close to a state border. Further, cross-border travel will be more important for county-level analysis such as we undertake below. To address this issue in both our state- and county-level analyses, we consider the impact of excluding those counties that directly border either another state or Mexico, i.e. those areas which are most 3 A potential further source of information on the behavioural response of teenagers in Texas to the parental consent law would have been the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS). In principal, YRBSS data on sexual behaviour are available biannually for 2001, 2003, 2005 etc. Unfortunately YRBSS data for Texas is not available for the key year of 2003, whilst the data for 2001 used a radically different sampling frame to that for subsequent surveys making comparisons over time difficult. See www.dshs.state.tx.us/chs/yrbs/pages/yrbs_faq.shtm for details. 10 likely to be affected by travel to access services outside of the State. Further, for the countylevel analysis, we also control for the presence of clinics in bordering counties including those counties within Texas and bordering countries in neighboring states. 5. Results 5.1 Impact on family planning attendance amongst minors We first undertake some preliminary analysis to explore whether the available evidence is consistent with the parental consent mandate having led to changes in family planning takeup. For this purpose, we use survey data of the number of female clients at publicly funded family planning clinics collected by the Alan Guttmacher Institute (AGI). We compare the rate of teenage clients reported at Texas clinics in 2001, before the funding change, and 2006, after the funding change. No surveys were carried out in the intervening years. Unfortunately data on take-up by adolescents are only available for under-20s and not specifically for minors which is likely to make it more difficult for us to observe any effect of parental consent. Clearly changes in clinic attendance from 2001 to 2006 may be influenced by factors other than parental consent. For this reason, we measure the change for adolescents relative to the change for older women. We also measure the change for adolescents in Texas relative to adolescents in other states in the Federal Region 6: Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico and Oklahoma. A useful feature of the AGI data is that the number of clients is provided separately for Title X-supported clinics. As mentioned above, these clinics are federally funded and, hence, were not directly affected by the 2003 parental support regulation. If any decrease in total attendance at family planning clinics amongst adolescents is due to the parental consent rule, we would expect the decrease to be dominated by non-Title X clinics. For this reason, we measure the relative change in take-up for adolescents at Title X and non-Title X clinics. The results of this exercise are reported in Table 1a. The deflators used for calculating rates are the numbers of women in each age group reported by the AGI to be in need of publicly supported contraceptive services.4 We also report p-values of a t-test of differences between different groups. 4 The AGI classify women aged below 20 as being in need of publicly funded contraception if she is sexually active, is fecund and neither intentionally pregnant nor trying to become pregnant. For women aged 20-44, there is an additional requirement that her family income is below 250% of the federal poverty level (see http://alanguttmacherinstitute.org/pubs/win/winmethods2006.pdf ). 11 Between 2001 and 2006, the estimated rate of attendance by teens at publicly funded family planning clinics in Texas went down from 36.9 to 25.2, a reduction of 31.7%. In other Region 6 states, the rate of attendance actually increased by 2.6% giving a relative difference of 34%. The rate of attendance for older women in Texas decreased by 15% and this suggests that some of the decrease amongst adolescents may have been part of a broader trend specific to Texas. However, the relative decrease for adolescents compared to older women in Texas is still just under 16%. All these relative differences are strongly statistically significant. We also calculate the difference-in-difference-in-differences by comparing the relative change in Texas (i.e. adolescents to older women) to the relative change in the other Region 6 states. In this case, the relative percentage decrease for Texas adolescents is lower (5.9%) but still statistically significant at conventional levels. A complementary approach is to estimate the relative change to attendance at affected (non-Title X) and unaffected (Title X) clinics and we report these results in Table 1b. Attendance by teenagers at affected clinics decreased by 36.9% and at unaffected clinics by 24.8%, a relative decrease of 12.2%. Amongst older women, attendance at affected clinics decreased by 12.5% and at unaffected clinics by 19.4%. The implied difference-indifference-in-differences effect on teenagers at affected clinics is a decrease of 19.0%. Again, all differences are statistically significant at conventional levels. A further issue is whether clinic attendance between the two periods may have been affected by other changes not linked to parental consent. The obvious examples are changes to the number of clinics in each county between the periods and shifts in the numbers from different ethnic/racial groups. For this reason, we estimate a regression model using counties as the unit of observation. The model we estimate is: attendanceit = consent + X + uit where attendance is the rate of attendance in each county (deflated by the total female population in the relevant age group), i; t takes the values 2001 and 2006; consent is a dummy variable for the year 2006 when the parental consent law was in effect; X is a vector of other variables that may have affected clinic attendance, specifically the proportion of the population that is Hispanic (Hispanic), the proportion that is black (Black) and the number of family planning clinics per 1000 population (clinics). We include fixed effects for each county and, due to the fact that some observations of the dependent variable are zero, estimate the model in levels (rather than in logs) and weight the regressions by the female population in each county. We estimate the model for 12 teenagers and older women (using the population aged 15 to 19 and 20 to 44, respectively) and also separately for those counties with at least one affected clinic and for those counties with no affected clinics. The coefficients on the various models are reported in Table 1c. The results are consistent with the univariate analysis above. Looking at all counties and after controlling for the number of clinics and racial/ethnic mix, the rate of family planning take-up is estimated to go down by 6.3 after the imposition of parental consent for state-funded contraception, representing a drop from the mean 2002 level of about 50%. When we split up the sample, we find that the decrease is considerably larger for counties with at least one affected clinic than those without (a decrease of 7.6 versus 2.14). The decrease for older women is very much smaller and statistically insignificant. Further, for older women, we observe very little difference in the parental consent effect between counties with an affected clinic and those without. So although the estimated effect varies depending on the comparison group and methodology, there is consistent and strong evidence that attendance by adolescents at family planning clinics decreased considerably before and after the change to parental consent in 2003. Further, the breakdown by those clinics affected and unaffected by the change is consistent with the parental consent statute being the cause of a significant part of that decrease. Given that the data on adolescents include older teenagers who would have been unaffected by the parental consent law, it is likely that the magnitude of the impact on minors was even greater than that suggested by the discussion above. The numbers of adolescents who appear to have been affected by the parental consent change are significant. On the assumption that the observed relative decreases in family planning attendance can be attributed to those affected by the parental consent ruling (i.e. minors), the estimated change relative to older women in Texas (the D-D estimate in Table 1a of 15.9%) would imply more than 20,000 fewer minors attending family planning clinics annually. Frost, Henshaw and Sonfield (2010) argue that, on average, 208 unintended pregnancies are averted for each 1000 attendees at publicly funded clinics. Other things equal, this implies that the parental consent ruling should have increased unintended pregnancies amongst Texan minors by over 4,000 per year. Even on the basis of the smallest estimated effect of 5.9% (the DDD estimate from Table 1b) this implies a potential 1,600 extra pregnancies. Of course other things are not equal in that some of the affected minors will have accessed alternative means of family planning such as purchasing contraception or crossing 13 state or federal lines. Other minors may have chosen to reduce (or eliminate) their engagement in risky sexual activity. Depending on the relative numbers in each of these categories, the actual impact on unintended pregnancies is impossible to ascertain a priori. We now go on to attempt to estimate the actual impact of mandating parental consent for state-funded contraception on pregnancy, birth and abortion rates amongst minors. 5.2 Impact on pregnancy and abortion rates amongst minors 5.2.1 State–level estimates Figure 1 illustrates the trend in pregnancy rates in Texas before and after the parental consent ruling for three age groups: 18 year olds (the control group), under-18s (i.e. all those affected) and under-16s. Differences in pregnancy rates across ethnic and racial boundaries have been well documented. For this reason we present trends for the whole population in each age group and for three racial and ethnic sub-groups: non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics. For ease of comparison, all rates are normalized to 100 in 2002. The graphs provide little evidence that conception rates amongst minors increased (either absolutely or relative to the rate amongst 18-year olds) from the introduction of parental consent in 2003. Pregnancy rates for all groups are decreasing the years immediately prior to the parental consent mandate being introduced. Rates continue to decrease in 2003 (the first year in which the mandate was in effect), but the 18-year old rate starts to increase from 2004. The rate for under-18s decreases relatively less fast in the first year of the mandate but (relatively) faster in subsequent years. For under-16s, the rate decreases faster than that for 18 year olds in each year after the mandate. The racial/ethnic sub-groups show a similar pattern with the exception that the rate for under-18 blacks decreases faster than that for 18 year olds even in 2003. In Table 2a we report the differences (D) and relative differences (DD) for each age group and racial/ethnic sub-group between 2002 (the year before the mandate) and 2003-5 (the first three years of the mandate). In all cases, the point estimates of the relative differences are negative, but they are generally small in magnitude and statistically insignificant. The point estimates of the relative differences tend to be somewhat larger for younger teenagers and we find statistically significant, negative effects, for some of the racial/ethnic sub-groups. In Table 2b we report the relative differences (DDs) for a number of alternative specifications. These can be summarized as follows: 14 (i) To help disentangle any difference between short and long and run effects, we report separate estimates for each year from 2002 to 2005. (ii) We report effects on abortion and birth rates separately. Note that separate estimates for abortion and birth rates are not reported here for reasons of space but are available on request from the authors. (iii) We alter the definition of the control group in two ways. First, some of those who conceive aged 18 are likely to have made decisions about contraceptive use when they were still 17 and, hence, will have been affected by the parental consent mandate. To allow for this, we exclude from the control group those aged younger than 18 and three months. Second, we expand the control group to include also those aged 19 at conception. (iv) A related issue is that some minors who conceived in 2003 will have accessed contraceptive services during 2002, before the parental consent mandate was in place. To allow for this, in the third column of Table 2b, we report estimates based on the age of the mother at the likely time of any visit to a family planning clinic, namely three months before conception. (v) We control for the possibility of cross-border travel in two ways. First, we exclude from the analysis any county which borders either Mexico or another U.S. state. Second we report the relative difference for rural counties alone. The latter experiment reflects the fact that some urban areas in Texas cover more than one county and that, in such cases, accessing clinics in neighboring counties is likely to be much easier. Consistent with the baseline estimates, the relative differences in these alternative specifications are generally small, negative and, for under-18s, of low statistical significance. The estimated effects tend to become more negative, the further away we get from the introduction of the policy in 2003 and, in 2005, we observe a statistically significant reduction in relative pregnancy rates for under-16s. This is consistent with the argument of Arcidiacono et al (2011) that teenagers are more likely to change their behavior to avoid risk in the long rather than short run. We also find significantly negative effects for under-16s in some of the specifications, notably when 19-year olds are included in the control group, using estimated age at clinic visit and when excluding border counties. To summarize, the state-level estimates provide no evidence that parental consent for federally-funded contraception led to an increase in pregnancy rates for minors relative to older teenagers, unaffected by the ruling. Indeed in some specifications we find a statistically 15 significant relative decrease in pregnancy rates for younger teens and there is also some evidence of a differential effect in the short and long run. It is possible, however, that those significant effects which are observed in some of the state-level estimates are due to nationwide effects that are contemporaneous with, but not caused by, the Texas parental consent mandate. For this reason, we now go on to use the county-level data to investigate whether those areas with clinics that were directly affected by the parental consent mandate experienced significantly different changes in pregnancy rates to those areas without such clinics. 5.2.2 County-level estimates In Tables 3a and 3b, we report the county-level DD and DDD estimates of the effect of parental consent for state-funded contraception on our two treatment groups: under-18s and under-16s. In each case, we report separate estimates for 2003, 2004 and 2005, all relative to the base year of 2002. Once we have dropped observations not within the common support region of the propensity score estimator, the sample size is 236 counties for the under-18 estimates (comprising 110 counties in the treatment group and 126 in the control) and 233 for the under-16 estimates (110 in the treatment and 123 in the control). The sign of the estimated effects varies depending on the year and the treatment group. For both age groups, the relative difference (DDD) is positive in the first year of parental consent (2003) but negative in later years. However, none of the estimated effects approach statistical significance at conventional levels.5 We next go on to report (in Tables 4a and 4b) regressions in which the treatment effect can vary for different racial/ethnic groups. We find some evidence that the effects are relatively different for Hispanics. For example, both the DDD estimates in 2003 suggest that parental consent had a smaller effect for Hispanics than for whites. However, the overall impact on pregnancy rates continues to be statistically insignificant in every case. In Tables 5a and 5b we report the DD and DDD estimates for a series of robustness checks and alternative specifications. These include the same checks that we carried out for the state-level estimates along with three further checks as follows: (i) We specify pregnancy rates in natural logarithms rather than levels. This allows us to interpret the coefficients as percentage changes, but does mean that counties with zero observations in a particular category are dropped. 5 These (and subsequent results) are robust to the use of alternative sets of variables in the probit model 16 (ii) We consider two alternative approaches to defining which counties are in the treatment and/or control categories. The first alternative approach (Treatment definition 2) is to exclude from the treatment group any county in which there is a Title X clinic. The motivation for this is that in such counties, minors who would have attended an affected (i.e. non-Title X clinic) will find it relatively easy to switch to their (unaffected) local Title X clinic. The second alternative (Treatment definition 3) further controls for the possibility that affected minors will switch to an unaffected clinic in a neighboring county, either within or outside the state. With this approach, we exclude from the treatment group any county whose bordering counties have more than one unaffected (i.e. Title X) clinic, whilst we exclude from the control group any county whose bordering counties have more than one unaffected (i.e. non-Title X) clinic. Although these approaches may allow a more precise measurement of the effect of the parental consent mandate, they do lead to a considerable reduction in the sample sizes, especially after imposing the common support condition. For Treatment definition 2 the total sample sizes go down to 125 counties for the under-18 estimates (72 in the treatment and 53 in the control) and 135 for under-16s (72 in the treatment and 63 in the control). For Treatment definition 3, the sample sizes go down to just 47 for under-18s (25 in the treatment and 22 in the control) and 45 for under-16s (25 in the treatment and 20 in the control). (iii) To control for the possibility that counties with particularly small populations may be overly weighted in the estimation, we exclude any county with a population in the main childbearing years (between 15 and 44) of less than 500. This results in 9 counties being dropped from the analysis. In an alternative approach, we also estimate the DD and DDD models using regressions weighted by the female population aged 15 to 19 rather than by propensity scores.6 For under-18s (reported in Table 5a), the alternative specifications show a similar pattern in the sign of effects to the state-level estimates in that the estimated effects are more often negative (or less positive) in later years and for abortion rates and are more often positive for birth rates. The magnitude of the coefficients varies considerably across the specifications and in particular for alternative treatment definitions, but none of the estimated differences are statistically significant at the 5% level. 6 The results are robust to alternative cut-off points for defining small counties. Note that it is not possible to combine population weights with the propensity score weights in our main estimates. 17 The results for under-16s are reported in Table 5b. Again, the signs of the effects follow a similar pattern to those from the state-level estimates, with a mixture of positive and negative effects. However, in contrast to the state-level, none of the negative effects are statistically significant. In the case of Treatment Definition 3 in 2005, the DD estimate is positive and strongly significant. The small sample size in this specification, along with the fact that the statistical significance of this estimate is not robust to the DDD estimation, limits the inference that can be placed on this estimate. It does, however, stand as a notable exception to the general pattern of results.7 To summarize, using both state-level and county-level data, we find very little evidence that the introduction of mandatory parental consent for the provision of state-funded contraception to minors in Texas in 2003 led to an increase in pregnancies amongst minors. Our point estimates provide some evidence that parental consent may have had different effects for younger relative to older minors, for abortion relative to birth rates and in the long run relative to the short term. Rarely, however, do we find the estimated effects to be statistically significant. 6. Discussion and Conclusions Several legislatures in the U.S. and elsewhere continue to discuss the most appropriate way to involve parents in minors’ decisions surrounding sexual health. Texas is one of just two states in which parental consent has been made mandatory before state-funded contraception can be provided to minors. Economic models of teenage behavior suggest that the impact of parental consent for contraception will have ambiguous effects on pregnancy rates amongst minors. To the extent to which parental consent restricts the take-up of contraception amongst minors, pregnancy rates will increase. However, if some minors reduce the level of sexual risk taking, pregnancy rates may decrease. Previous work, based on conjectural responses of minors, predicted that net effect of the Texas parental consent mandate would be to increase the unwanted pregnancy rate amongst minors rate by a very considerable amount. This paper has provided the first test of these predictions using actual data before and after parental consent was introduced in 2003, and using robust statistical methodology that controls for both observable and unobservable characteristics affecting county-level Title X clinic attendance. 7 This magnitude and significance of this estimate are also not robust to other specifications, e.g. estimating in logs and excluding border counties. 18 At the state level, we find no evidence that mandating parental consent for statefunded contraception increased pregnancy rates amongst minors. For the youngest age group (those aged under-16), there is some evidence that, at the State level, pregnancy rates went down after the parental consent mandate relative to older teenagers who continued to be able to obtain state-funded contraception without parental consent. We also use statistical matching estimators on county-level data to compare the changes in pregnancy rates between counties with family planning clinics affected by the mandate relative to those counties without such clinics. This approach reveals very little impact from the parental consent mandate, even for the under-16 group. Taken together, the evidence suggests that, in contrast to the predictions of the conjectural evidence, parental consent for state-funded birth control in Texas does not appear to have increased underage pregnancy rates in the state. One explanation for this finding is that minors (in aggregate) respond to actual parental involvement laws by reducing their level of risky sexual activity to a greater extent than suggested by their conjectural responses to potential laws. An alternative (and possibly complementary) explanation is that minors were more successful than anticipated in accessing birth control from alternative sources that were not subject to the parental consent statute. The fact that our findings are robust to controls for cross-border travel suggests that such substitution is unlikely to explain our results fully. However, the fact that we are not directly able to observe take-up of birth control by minors from different sources, means that it cannot be discounted. Our findings will be of most direct relevance to other states considering mandating parental consent for the provision of state-funded birth control to minors. The evidence we present here suggests that the risk of thereby increasing rates of underage pregnancy is low. We can be less sure about whether our results would generalize to broader parental consent mandates. The results may well have been different had parental consent been mandated for the provision of birth control to minors from federally funded clinics too. That said, the Texas statute provides the only large-scale change in parental consent legislation to have been enacted in the world and, as such, the experience of the Texan law will be of considerable interest to any legislature, in the U.S. or overseas, considering the issue of parental involvement for birth control. Finally, our results suggest that policy makers and academics should exercise caution before drawing policy inferences from simulation work based on conjectured, rather than actual, responses. 19 References Akerlof, G.A., J.L. Yellen and M.L. Katz (1996), ‘An analysis of out-of-wedlock childbearing in the United States’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 111 (2, May): 277-317. Arcidiacono, P., A. Khwaja and L. Ouyang (2011), ‘Habit Persistence and Teen Sex: could increased access to contraception have unintended consequences for Teen Pregnancies?’ Duke University Working Paper, http://econ.duke.edu/~psarcidi/teensex.pdf, accessed 5th October 2011. Becker, G.S. (1963), A Treatise on the Family, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. Busso, M., J. DiNardo and J. McCrary (2009), ‘New Evidence on the Finite Sample Properties of Propensity Score Matching and Reweighting Estimators’, IZA Discussion Paper, No. 3998. Colman S., T. Joyce and R. Kaestner (2008), ‘Misclassification Bias and the Estimated Effect of Parental Involvement Laws on Adolescents’ Reproductive Outcomes’ American Journal of Public Health, 98(10): 1881-5. Evans W.N., W.E Oates and R.M. Schwab (1992), ‘Measuring peer group effects: a study of teenage behavior’, Journal of Political Economy, 100(5, Oct): 966-91. Frost, J.J., S.K. Henshaw and A. Sonfield (2010), Contraceptive Needs and Services: national and state data, 2008 update, AGI, New York: Guttmacher Institute. Franzini, L., E. Marks, P.F. Cromwell, et al. (2004), ‘Projected economic costs due to health consequences of teenagers’ loss of confidentiality in obtaining reproductive health care services in Texas’, Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 158: 1140-6. Girma, S. and D. Paton (2011) ‘The Impact of Emergency Birth Control on Teen Pregnancy and STIs’, Journal of Health Economics,30: 373-80. Girma, S. and D. Paton (2006), ‘Matching estimates of the impact of over-the-counter emergency birth control on teenage pregnancy’, Health Economics, 15 (Sept): 102132. Harper, C., L. Callegari, T. Raine, M. Blum and P. Darney (2004), ‘Adolescent clinic visits for contraception: Support from mothers, male partners and friends’, Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 36(1): 20-26. Hirano, K., G.W. Imbens, and G. Ridder (2003), ‘Efficient Estimation of Average Treatment Effects Using the Estimated Propensity Score’, Econometrica, 71 (4): 1161-1189. Jones, R.K., A. Purcell, S. Singh, and L.B. Finer (2005), ‘Adolescents’ reports of parental knowledge of adolescents’ use of sexual health services and their reactions to 20 mandated parental notification for prescription contraception’. JAMA, 293(3): 340348. Joyce T., R. Kaestner and S. Colman (2006), ‘Changes in Abortions and Births and the Texas Parental Notification Law’, New England Journal of Medicine, 354(10, March): 1031-8. Kearney, M.S. and P.B. Levine (2009), ‘Subsidized contraception, fertility and sexual behavior’, Review of Economics and Statistics, 9(1): 137-51. Klick, J. and T. Stratmann (2008), ‘Abortion access and risky sex among teens: parental involvement laws and sexually transmitted diseases’, Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, 24 (1, May): 2-21 Levine, P.B. (2004), Sex and Consequences: abortion, public policy and the economics of fertility, Princeton: Princeton University Press. Levine, P.B. (2003), ‘Parental involvement laws and fertility behavior’, Journal of Health Economics, 22(5): 861-7. New, M.J. (2011). ‘Analyzing the effect of anti-abortion U.S. state legislation in the postCasey era’, State Politics and Policy Quarterly, 11 (1, March): 28-47. Oettinger G.S. (1999), ‘The Effects of Sex Education on Teen Sexual Activity and Teen Pregnancy’, Journal of Political Economy, 107(3): 606-44. Paton, D. (2002), ‘The economics of abortion, family planning and underage conceptions’, Journal of Health Economics, 21 (2, March): 27-45 Raymond, E.G., J. Trussell, J. and C.B. Polis (2007), ‘Population effect of increased access to emergency contraception pills: a systematic review’, Obstetrics & Gynecology, 109 (1, Jan):181-8. Reddy, D.M., R. Fleming, and C. Swain (2002), ‘Effect of mandatory parental notification on adolescent girls’ use of sexual health care services’, JAMA, 288(6): 710-714. Rosenbaum, P.R. and D.B. Rubin (1983), ‘The Central Role of the Propensity Score in Observational Studies for Causal Effects’, Biometrika, 70 (1): 41-55. Wooldridge, J.M. (2002), Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data, Boston: MIT Press. Zavodny, M. (2004), ‘Fertility and parental consent for minors to receive contraceptives’, American Journal of Public Health, 94(8): 1347-1351. Zavodny, M. (2005), ‘Erratum in: Fertility and parental consent for minors to receive contraceptives’, American Journal of Public Health, 95 (2): 192. 21 Figure 1: Pregnancy rates in Texas by age, race and ethnicity, 2000-2006 1st year of parental consent 110 120 110 2002=100 2002=100 105 100 100 90 95 90 80 2000 2002 2004 2006 2000 year All 18s All u16s 120 2002 2004 2006 year All u18s White 18s White u16s White u18s 110 1st year of parental consent 1st year of parental consent 105 2002=100 110 2002=100 1st year of parental consent 100 100 95 90 90 80 85 2000 2002 2004 2006 year Black 18s Black u16s 2000 2002 2004 year Black u18s Hispanic 18s Hispanic u16s 22 Hispanic u18s 2006 Table 1a: Relative impact of parental consent on family planning attendance rates amongst teenagers Texas Rest of Region 6 U20 20-44 U20 20-44 2001 36.9 41.4 39.3 40.8 2006 25.2 34.8 40.4 46.0 % change -31.7*** -15.9*** 2.6*** 12.6*** (0.24) (0.15) (0.37) (0.24) DD -15.9*** -10.0*** (0.28) (0.44) DDD -5.9*** (0.52) Notes (i) Region 6 is the Federal Region comprising Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas. (ii) Rates are calculated per 100 women classified by AGI as being in need of publicly supported contraceptive services. (iii) Standard errors for the difference in the percentage changes are in parentheses and are calculated using the method described in www.census.gov/acs/www/Downloads/data_documentation/Accuracy/PercChg.pdf (iv) Significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1% Table 1b: Relative impact of parental consent on family planning attendance rates amongst teenagers: affected and unaffected clinics U20 20-44 Affected Unaffected Affected Unaffected clinics clinics clinics clinics 2001 21.2 15.8 21.3 20.0 2006 13.4 11.9 18.7 16.2 -24.8*** -12.5*** -19.4*** % change -36.9*** (0.32) (0.43) (0.25) (0.24) (SE) DD -12.2*** 6.9%*** (SE) (0.54) (0.34) DDD -19.0*** (SE) (0.64) Notes (i) Unaffected clinics are family planning clinics receiving Title X funding. (ii) Rates are calculated per 100 women classified by AGI as being in need of publicly supported contraceptive services. (iii) Standard errors for the difference in the percentage changes are in parentheses and are calculated using the method described in www.census.gov/acs/www/Downloads/data_documentation/Accuracy/PercChg.pdf (iv) Significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1% 23 Table 1c: County-level regression estimates of impact of parental consent on family planning attendance U20 20-44 All Affected Non-affected All Affected Non-affected counties counties counties counties consent -6.27*** -7.63*** -2.14* -1.31 -1.26 -1.08 (2.18) (27.93) (1.10) (1.47) (1.97) (0.93) clinics 1.38 0.12 2.76** 12.90*** 12.85* 12.90** (0.87) (12.86) (1.15) (4.24) (6.50) (5.37) Hispanic 0.22 0.55 -0.36 0.023 0.028 -0.06 (0.18) (0.74) (0.59) (0.08) (0.94) (0.06) Black 0.23 0.22 0.77 0.06 0.065 0.13 (0.71) (1.01) (0.65) (0.18) (0.31) (0.14) Sample size 483 County effects yes 198 yes 285 yes 482 yes Notes (i) Regressions are weighted by female population in each county. (ii) Standard errors in parentheses. (iii) Significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1%. 24 197 yes 285 yes Table 2a: State-level estimates of effect of parental consent on pregnancy to minors Variable Age group Pregnancy Pregnancy D DD rate 2002 rate 2003-5 18 132.79 127.6 -4.61*** n/a ( 8.45) U18 69.39 66.4 -4.72*** -0.12 All (6.50 ) (1.07) U16 17.67 16.49 -7.02*** -2.41 ( 1.25) (1.51) 18 87.13 82.45 -6.02*** n/a (1.52 ) Non-Hispanic U18 36.55 34.42 -6.21*** -1.84 White (1.32 ) (2.01) U16 7.58 6.63 -13.52*** -7.49*** ( 2.90) (3.27) 18 156.49 153.2 -2.48 n/a (2.19) Non-Hispanic U18 81.06 75.14 -8.24*** -5.75** Black (1.67) (2.76) U16 22.59 20.67 -9.09*** -6.61* (3.04) (3.75) 18 183.50 176.3 -4.85*** n/a (1.19) U18 107.90 102.0 -6.27*** -1.42 Hispanic (0.86) (1.47) U16 28.53 26.22 -8.69*** -3.84* (1.59) (1.98) Notes: (i) Rates are per 1000 women at estimated age of conception. For under-18s, the female population aged 15-17 is used as the deflator, whilst for under-16s, the female population aged 13-15 is used. (ii) D is the difference in (log) rates for the respective age group from 2002 to 2003-5; DD is the difference relative to 18 year olds, as specified in equation (1). Coefficients are multiplied by 100 so that they can be interpreted as percentage (relative) differences (iii) Standard errors in parentheses. (iv) Significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1%. . 25 Table 2b: State-level DD estimates of effect of parental consent: alternative specifications Specification Under 18 Under 16 Baseline (from Table 2a) -0.12 -2.41 (1.07) (1.51) 2002 vs 2003 1.58 -0.23 (1.31) (1.86) 2002 vs 2004 -0.30 -2.25 (1.30) (1.86) 2002 vs 2005 -2.19* -4.71** (1.30) (1.85) Abortion rates 3.85 -3.19 (2.47) (3.64) Birth rates -1.53 -2.99* (1.16) (1.65) Control group: 18.25 < 19 -0.71 -3.01* (1.15) (1.57) Control group: 18.25 – 19 -1.18 -3.47** (0.89) (1.39) Est. age at clinic visit -1.42 -4.32** (1.03) (1.44) Excluding border counties -1.91 -3.66** (1.19) (1.69) Excluding urban counties 1.08 0.67 (2.73) (3.89) Notes: (i) Estimates are the (log) differences from 2002 relative to the differences in the control group (18-year olds unless stated otherwise) as specified in equation (1). Coefficients are multiplied by 100 so that they can be interpreted as percentage (relative) differences. (ii) Standard errors in parentheses. (iii) Significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1%. 26 Table 3a: Treatment effects on under-18 pregnancy rates 2003, 2004 and 2005 versus 2002: DD and DDD combined with propensity score reweighed regressions DD treatment poverty lag pregnancies urban border Hispanic Black Title X (2001) constant Sample size Adjusted R2 2003 1.387 (2.627) 21.815 (42.511) -0.424*** (0.079) -2.547 (2.695) 3.360 (3.083) 0.009 (0.083) -0.317 (0.196) -3.441 (2.257) -1.185 (5.232) 236 0.282 2004 -5.809 (4.417) -104.880 (132.000) -0.700*** (0.145) -7.829 (7.085) -4.073 (5.506) 0.538 (0.380) 0.609 (0.388) -5.755 (3.968) 0.137 (14.185) 236 0.275 DDD 2005 -1.038 (3.406) -78.937 (67.677) -0.565*** (0.127) -6.018 (4.506) -7.675* (4.011) 0.387** (0.195) 0.256 (0.266) -4.744 (2.963) 0.498 (7.939) 236 0.291 Notes: (i) Standard errors in parentheses (ii) Significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1% 27 2003 4.103 (10.907) -72.365 (256.719) -0.482 (0.351) 0.122 (14.373) -1.745 (14.051) 0.715 (0.720) -0.194 (0.871) 1.608 (11.489) -6.519 (28.163) 236 0.036 2004 -10.434 (11.145) -386.273 (358.593) -0.661*** (0.163) -23.878 (18.924) -7.761 (13.814) 1.336 (1.035) 1.626 (1.062) -11.743 (10.919) 29.537 (37.723) 236 0.084 2005 -7.261 (10.172) -171.860 (203.342) -0.629** (0.288) -11.674 (11.377) -6.824 (13.268) 0.997* (0.557) 0.755 (0.705) -8.450 (7.773) 1.402 (23.791) 236 0.074 Table 3b: Treatment effects on under-16 pregnancy rates 2003, 2004 and 2005 versus 2002: DD and DDD combined with propensity score reweighed regressions DD treatment poverty lag pregnancies urban border Hispanic Black Title X (2001) constant Sample size Adjusted R2 2003 0.026 (1.307) -2.871 (15.858) -0.559*** (0.097) -2.257* (1.261) -1.252 (1.595) 0.007 (0.040) -0.044 (0.079) -1.557 (1.786) 1.500 (2.444) 233 0.379 2004 0.266 (1.314) 0.291 (16.780) -0.582*** (0.094) -2.047* (1.176) -1.714 (2.021) -0.001 (0.041) 0.053 (0.076) -3.140*** (1.159) 0.325 (2.711) 233 0.318 DDD 2005 -0.837 (1.995) -86.904* (52.312) -0.563*** (0.088) -5.445* (2.969) -2.822 (2.397) 0.280* (0.155) 0.260 (0.163) -3.053 (1.893) 6.585 (5.478) 233 0.270 Notes: (i) Standard errors in parentheses (ii) Significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1% 28 2003 2004 0.660 -5.746 (10.486) (9.330) -85.138 -264.558 (250.136) (239.040) -1.420** -0.690** (0.583) (0.320) 0.723 -17.908 (14.624) (13.520) -7.315 -8.345 (13.198) (11.681) 0.832 0.886 (0.757) (0.718) 0.319 1.076 (0.800) (0.753) -6.228 -13.537 (10.636) (9.302) -9.216 26.373 (27.270) (26.188) 233 233 0.063 0.042 2005 -4.733 (9.590) -217.502 (192.065) -0.482 (0.593) -10.672 (10.967) 2.703 (11.971) 0.883 (0.541) 0.810 (0.661) -8.725 (8.706) 10.905 (21.479) 233 0.024 Table 4a: Treatment effects on under-18 pregnancy rates 2003, 2004 and 2005 versus 2002: DD and DDD combined with propensity score reweighed regressions by race/ethnicity DD DDD Poverty 2003 2.191 (2.625) -0.258** (0.114) -0.472 (0.294) 27.165 2004 -5.024 (4.305) -0.334* (0.199) -0.155 (0.376) -99.633 2005 -0.444 (3.240) -0.269* (0.155) -0.058 (0.345) -74.955 2003 8.005 (10.943) -1.387*** (0.504) -1.787 (1.134) -46.354 2004 -9.832 (10.953) -0.423 (0.569) 0.494 (0.985) -382.193 2005 -5.708 (10.027) -0.837 (0.570) 0.341 (1.120) -161.415 lag pregnancies (41.601) -0.423*** (129.292) -0.708*** (65.779) -0.573*** (249.201) -0.492 (354.225) -0.685*** (198.208) -0.664** (0.079) -2.211 (2.728) 4.345 (3.166) 0.082 (0.087) -0.204 (0.223) -3.385* (1.989) -6.018 (5.390) 236 0.294 (0.150) -6.995 (6.561) -3.176 (5.575) 0.647 (0.428) 0.607* (0.328) -5.416 (3.790) -5.309 (12.680) 236 0.281 (0.125) -5.287 (4.344) -7.008* (4.199) 0.477** (0.220) 0.233 (0.278) -4.431 (3.012) -3.772 (8.157) 236 0.299 (0.356) 2.585 (13.736) 2.932 (15.093) 1.131 (0.795) 0.171 (0.824) 2.347 (12.158) -31.182 (27.834) 236 0.067 (0.166) -22.218 (17.619) -7.202 (14.425) 1.496 (1.179) 1.400 (0.885) -10.910 (10.641) 23.891 (34.934) 236 0.084 (0.293) -8.944 (10.924) -5.184 (14.295) 1.293** (0.638) 0.514 (0.670) -7.173 (7.714) -10.931 (26.597) 236 0.094 Treatment treatment*Hispanic treatment* Black Urban Border Hispanic Black Title X (2001) constant Sample size Adjusted R2 Notes: (i) Standard errors in parentheses (ii) Significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1% 29 Table 4b: Treatment effects on under-16 pregnancy rates 2003, 2004 and 2005 versus 2002: DD and DDD combined with propensity score reweighed regressions by race/ethnicity DD treatment treatment*Hispanic treatment* Black poverty lag pregnancies urban border Hispanic Black Title X (2001) Constant Sample size Adjusted R2 DDD 2003 2004 2005 2003 0.053 (1.324) -0.032 (0.059) 0.007 (0.201) -2.251 (15.737) -0.565*** (0.100) -2.153* (1.259) -1.207 (1.613) 0.019 (0.041) -0.049 (0.088) -1.554 (1.768) 0.959 (2.386) 233 0.374 0.262 (1.336) 0.073 (0.057) -0.081 (0.123) -0.841 (15.725) -0.563*** (0.098) -2.343* (1.202) -1.743 (2.024) -0.032 (0.048) 0.085 (0.088) -3.166*** (1.166) 1.450 (2.893) 233 0.319 -0.438 (1.985) -0.159 (0.118) -0.259 (0.168) -82.601 (51.420) -0.575*** (0.101) -5.212* (2.786) -2.277 (2.616) 0.330* (0.186) 0.319** (0.159) -3.131 (1.897) 3.441 (5.290) 233 0.277 3.254 (10.646) -1.527*** (0.551) -1.108 (1.118) -49.640 (238.161) -1.627*** (0.615) 4.268 (13.395) -3.613 (14.245) 1.371 (0.875) 0.477 (0.712) -6.548 (11.254) -37.204 (25.937) 233 0.108 Notes: (i) Standard errors in parentheses (ii) Significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1% 30 2004 -6.311 (9.503) -0.186 (0.539) 0.847 (1.023) -264.371 (234.248) -0.781** (0.351) -16.551 (12.408) -8.977 (12.115) 0.995 (0.867) 0.806 (0.621) -13.274 (9.208) 24.531 (24.750) 233 0.041 2005 -4.197 (9.812) -0.766 (0.546) 0.297 (1.114) -203.280 (189.473) -0.643 (0.620) -8.090 (10.372) 3.621 (12.962) 1.190* (0.641) 0.638 (0.644) -8.622 (8.342) -1.781 (24.043) 233 0.041 Table 5a: Treatment effects for under-18s: alternative specifications Specification DD 2003 Baseline (from Table 3a) Log (pregnancies) Abortion rates Birth rates Treatment definition 2 Treatment definition 3 2004 1.387 -5.809 (2.627) (4.417) 0.024 -0.024 (0.050) (0.049) -0.598 0.370 (1.271) (1.542) 1.985 -6.179 (2.513) (4.103) -0.343 -14.259 (3.906) (9.299) -13.140* 3.813 (7.345) (10.847) 2003 2004 2005 -1.038 (3.406) 0.054 (0.047) 0.300 (2.264) -1.338 (2.858) -2.584 (6.395) 11.470 (7.550) 4.103 (10.907) 0.044 (0.084) 5.398 (3.416) -1.295 (10.144) 2.061 (21.119) 13.372 (22.543) 1.567 (9.899) -3.677 (7.829) 5.826 (9.469) 1.866 (13.053) 6.962 (8.924) 4.616 (14.025) 3.752 (4.435) -10.434 (11.145) -0.020 (0.065) 3.295 (2.981) -13.729 (11.163) -36.137 (23.218) 7.987 (19.697) -12.411 (10.681) -11.810 (10.579) -12.144 (8.571) -12.219 (15.246) -1.550 (6.277) -15.418 (13.774) 2.157 (3.895) -7.261 (10.172) 0.012 (0.084) 2.025 (2.971) -9.286 (8.946) -17.663 (17.361) 24.747 (26.934) -11.459 (9.795) -7.770 (5.978) 5.631 (11.797) -4.339 (11.271) -3.967 (9.358) -13.266 (12.884) 7.938* (4.721) Control group: 18.25 < 19 n/a n/a n/a Control group: 18.25 – 19 n/a n/a n/a Est. age at clinic visit -1.161 (2.714) 1.506 (3.336) 0.770 (2.598) 3.154 (3.272) -0.013 (1.408) -6.882 (5.000) -5.486 (5.920) -3.195 (2.867) -6.868 (5.554) -0.512 (1.565) 2.906 (3.793) -0.730 (3.917) 0.568 (3.050) 0.262 (4.364) 0.176 (1.678) Excluding border counties Excluding small counties Excluding urban counties Population weighted DDD 2005 Notes: (i) In each case, the coefficient on treatment is reported along with standard errors in parentheses. (ii) significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1%. 31 Table 5b: Treatment effects for under-16s: alternative specifications Specification DD 2003 2004 2005 2003 Baseline (from Table 3a) 0.026 0.266 -0.837 0.660 (1.307) (1.314) (1.995) (10.486) Log (pregnancies) -0.043 -0.108 -0.087 -0.052 (0.083) (0.070) (0.079) (0.104) Abortion rates 0.061 -0.032 -1.155 4.230 (0.812) (0.847) (1.603) (2.961) Birth rates -0.035 0.297 0.318 -3.569 (1.166) (1.517) (1.486) (9.966) Treatment definition 2 0.018 0.594 -2.491 -7.317 (1.690) (2.010) (3.941) (21.017) * Treatment definition 3 0.321 7.454 9.307*** 9.291 (3.298) (4.160) (3.104) (20.834) n/a n/a Control group: 18.25 < 19 n/a 1.070 (9.822) n/a n/a Control group: 18.25 – 19 n/a -4.109 (8.381) Est. age at clinic visit 2.126 2.189 0.169 5.271 (1.736) (1.513) (2.075) (9.813) Excluding border counties -0.308 0.817 -0.854 0.367 (1.424) (1.468) (2.081) (11.197) Excluding small counties -0.007 0.560 0.385 5.388 (1.277) (1.261) (1.426) (7.900) Excluding urban counties 0.836 0.511 -0.657 -1.005 (1.628) (1.704) (2.530) (13.820) Population weighted -0.818 -0.281 -0.796 2.811 (0.807) (0.773) (0.804) (4.279) DDD 2004 -5.746 (9.330) -0.126 (0.089) 2.793 (2.524) -8.539 (9.322) -23.762 (18.898) 10.509 (20.449) -7.484 (8.724) -3.272 (8.955) -6.511 (9.059) -1.545 (10.203) 0.707 (6.510) -11.059 (11.957) 2.351 (3.681) Notes: (i) In each case, the coefficient on treatment is reported along with standard errors in parentheses. (ii) significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1%. 32 2005 -4.733 (9.590) -0.100 (0.106) 1.122 (2.737) -5.855 (8.457) -17.173 (15.924) 14.505 (23.372) -8.818 (8.842) -4.565 (5.756) 1.889 (11.957) -6.164 (9.988) -1.226 (8.451) -10.934 (12.559) 6.892 (4.382) Appendix Table A1: Definition and Source of Variables Variable Description Conceptions ending in either a live birth or an abortion per pregnancy rate treatment poverty thousand population. Miscarriages are excluded miscarriages. Population is the female population for the relevant area, age group and race/ethnicity classification. For under-16 rates, the female population aged 13-15 is used. Pregnancy rate lagged by two years. Conceptions per thousand population resulting in an induced abortion by area of residence. Conceptions per thousand population resulting in a live birth by area of residence. = 1 for years in which the parental consent ruling was in force (from 2003 on); = 0 otherwise. =1 if consent = 1 for affected counties only; = 0 otherwise. Total percentage of persons living below the poverty level urban =1 if the county is in an urban area; = 0 otherwise border =1 if the county borders either Mexico or another U.S. state; = 0 otherwise attendance Number of female contraceptive clients served at publicly supported family planning clinics. clinics Total number of publicly funded family planning clinics. Title X Number family planning clinics supported by the federal Title X program. Lag pregnancies abortion rate birth rate consent 33 Source Texas DSHS Center for Health Statistics: supplied to the authors Texas DSHS as above Texas DSHS as above n/a n/a Texas DSHS Center for Health Statistics, Texas Health Facts Profiles (various years). Texas DSHS Center for Health Statistics, County Designations. Texas DSHS Center for Health Statistics, County Designations. Guttmacher Institute, Contraceptive Needs and Services (2001 and 2006) Contraceptive Needs and Services (as above) Contraceptive Needs and Services (as above) Table A1: Marginal effects from the Probit regression of the determinants of county-level Title X clinic attendance (1) (2) U18s U16s Poverty 2.048** 1.945** (0.876) (0.879) Lag pregnancies -0.002 -0.006** (0.001) (0.003) Urban 0.299*** 0.288*** (0.089) (0.090) Border 0.136 0.138 (0.089) (0.090) Hispanic 0.007*** 0.008*** (0.002) (0.002) Black 0.008* 0.008* (0.005) (0.005) Title X (2001) -0.233*** -0.248*** (0.061) (0.062) Sample size 254 254 Notes: (i) Standard errors in parentheses (ii) Significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1% 34