OSCAR WILDE IN VERONA

advertisement

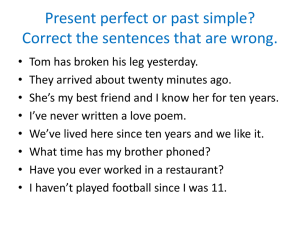

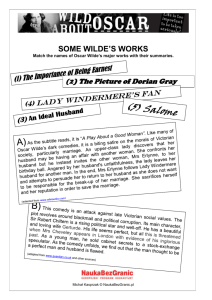

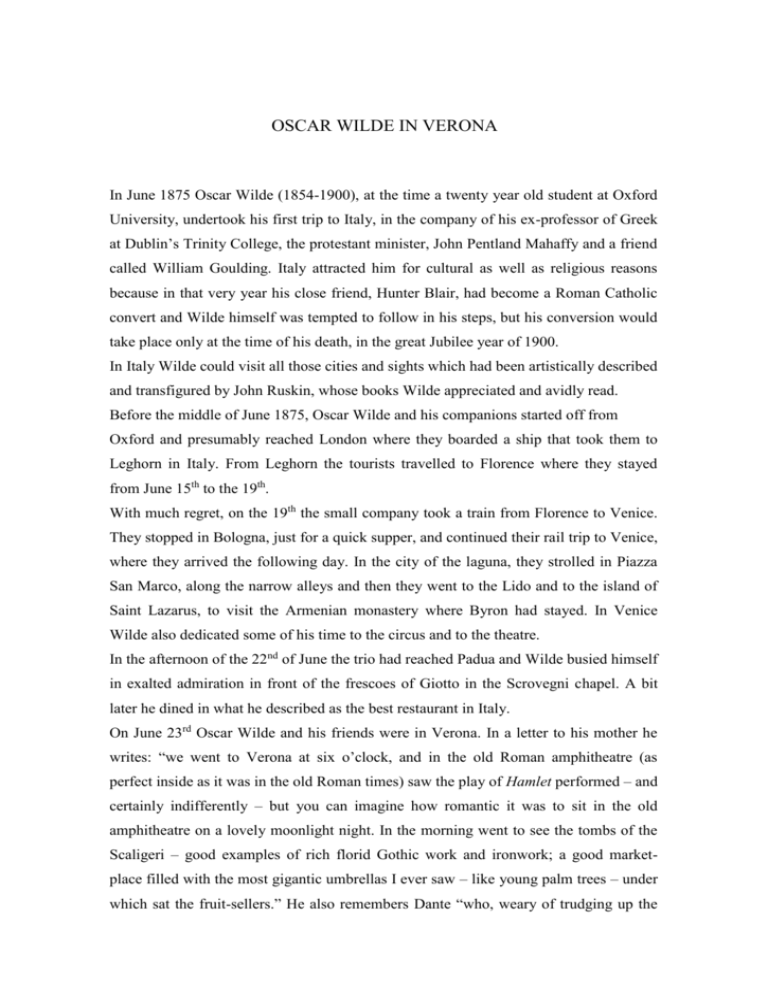

OSCAR WILDE IN VERONA In June 1875 Oscar Wilde (1854-1900), at the time a twenty year old student at Oxford University, undertook his first trip to Italy, in the company of his ex-professor of Greek at Dublin’s Trinity College, the protestant minister, John Pentland Mahaffy and a friend called William Goulding. Italy attracted him for cultural as well as religious reasons because in that very year his close friend, Hunter Blair, had become a Roman Catholic convert and Wilde himself was tempted to follow in his steps, but his conversion would take place only at the time of his death, in the great Jubilee year of 1900. In Italy Wilde could visit all those cities and sights which had been artistically described and transfigured by John Ruskin, whose books Wilde appreciated and avidly read. Before the middle of June 1875, Oscar Wilde and his companions started off from Oxford and presumably reached London where they boarded a ship that took them to Leghorn in Italy. From Leghorn the tourists travelled to Florence where they stayed from June 15th to the 19th. With much regret, on the 19th the small company took a train from Florence to Venice. They stopped in Bologna, just for a quick supper, and continued their rail trip to Venice, where they arrived the following day. In the city of the laguna, they strolled in Piazza San Marco, along the narrow alleys and then they went to the Lido and to the island of Saint Lazarus, to visit the Armenian monastery where Byron had stayed. In Venice Wilde also dedicated some of his time to the circus and to the theatre. In the afternoon of the 22nd of June the trio had reached Padua and Wilde busied himself in exalted admiration in front of the frescoes of Giotto in the Scrovegni chapel. A bit later he dined in what he described as the best restaurant in Italy. On June 23rd Oscar Wilde and his friends were in Verona. In a letter to his mother he writes: “we went to Verona at six o’clock, and in the old Roman amphitheatre (as perfect inside as it was in the old Roman times) saw the play of Hamlet performed – and certainly indifferently – but you can imagine how romantic it was to sit in the old amphitheatre on a lovely moonlight night. In the morning went to see the tombs of the Scaligeri – good examples of rich florid Gothic work and ironwork; a good marketplace filled with the most gigantic umbrellas I ever saw – like young palm trees – under which sat the fruit-sellers.” He also remembers Dante “who, weary of trudging up the steep stairs, as he says, of the Scaligeri when in exile in Verona, came to stay at Padua with Giotto in a house still to be seen there.” It was probably during this brief stay in Verona that Wilde was inspired to write the sonnet At Verona, published in the 1881 edition of his Poems. After Verona Wilde goes to Milan with his friends, but, having spent almost all his money, he must return home. Before leaving, on June 25th, he visits Arona, the town of St. Charles Borromeo, on Lake Maggiore, and from there he goes, by coach, via the Simplon Pass, to Lausanne. On the 28th he arrives in Paris and continues his voyage back to his home in Ireland. OSCAR WILDE’S OTHER ITALIAN JOURNEYS March 1877: Wilde, Mahaffy, Goulding and another student called George Macmillan travel from London to Genoa, passing through Paris and Turin. From Genoa they reach Ravenna and then Brindisi where they board a ship for Greece. During their return trip, they arrive in Naples and from there they take the train to Rome, where they remain a few days. On the 28th or 29th Oscar Wilde is back in Oxford. May-June 1894: Wilde, from Paris where he was staying, goes to Florence where, by chance he meets Andrè Gide, whose acquaintance he had made in Paris, and he visits the Anglo-Florentine writer, Vernon Lee (Violet Paget). September 1897-February 1898: After leaving Reading Gaol in May, Wilde goes to Dieppe, France, but, in a few month’s time, he reaches Lord Alfred Douglas in Naples. They first go to live at the Hôtel Royal des Etrangers, then they rent Villa Giudice, in Posillipo. Wilde and Douglas visit Capri together. Douglas leaves and Wilde, who by now lives alone at the Palazzo Bambino, 31 Santa Lucia, goes to Taormina. February 1899: From Nice where he was staying, Wilde goes to Genoa to pray on the tomb of his wife, Constance, who has died the year before. He goes to Switzerland and the, in April he is in Santa Margherita Ligure. April 1900: Wilde is in Palermo where he spends eight unforgettable days. He then goes to Naples for a short stay and moves on to Rome. On the 15th of April, Easter Sunday of that Jubilee year, Wilde receives the benediction from Pope Leo XIII. On November 30th 1900 Oscar Wilde dies in Paris at the Hôtel d’Alsace in rue des Beaux-Arts. Verona for Wilde is the town of Dante’s exile, an exile of hardships and sufferings that must be remembered by echoing the Biblical imprecation of Job. But Wilde is certainly exaggerating when he evokes the image of Dante in jail. This never happened and only poetical license can justify such a false representation of the real events. Probably the idea of the jailed poet was suggested to him by the romantic picture of Tasso in the prison of Ferrara, of which there’s a hint in The Soul of Man under Socialism. Perhaps when he was in prison, from 1895 to 1897, Wilde thought about this early prophetic poem and the meaning of being an imprisoned poet. Then he was fully conscious, as he says in his long letter, De Profundis (1897), addressed to Lord Alfred Douglas, that “At all costs I must keep Love in my heart. If I go into prison without Love what will become of my Soul?” “ I must keep Love in my heart today, else how shall I live through the day?” And throughout the epistle he repeats like a refrain: “Shallowness is the supreme vice.” The sonnet At Verona is directly linked to the long poem Ravenna (1878), through the inspiring influence of Dante, and also to The Ballad of Reading Gaol (1898), in which the poet invokes forgiveness for the prisoners by refusing the hellish conditions of the prison itself and the very idea of revenge exercised by society when it decrees the death penalty for criminals. BEFORE WILDE Although Verona was not always included in the classical itinerary of the Grand Tour, it soon became the chosen destination for all those travellers who were keen on a place full of cultural allure. For English speaking travellers the city was identified with the Shakespearean settings: it’s the scene of The Two Gentlemen of Verona, of the two world-renowned lovers, Romeo and Juliet, it’s always “fair Verona”, where young, infinite love never dies. It’s also the city that welcomed Dante Alighieri who dedicated his Divine Comedy to Cangrande della Scala; a place where every enthusiastic scholar of Dante of the nineteenth century wanted to be. George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788-1824), was in Verona in 1816 when he appreciated the medieval town which saw Dante in exile, but he also stopped at Juliet’s tomb and greatly admired the Arena. Whoever has eyes trained to see the marvels of the past can only rejoice at the wealth of architectural stratifications – Roman, Medieval, Renaissance – openly displayed by Verona in all its panoramic glory and rarely experienced by the tourist, even in other Italian cities. Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1803-1873) was in Italy in 1833 and under the Neapolitan sun he exclaimed: “Italy, Italy, while I write, your skies are over me – your seas flow beneath my feet.” The acclaimed author of The Last Days of Pompeii dedicated an essay to Juliet’s tomb in 1840, which he had visited in Verona. John Ruskin (1819-1900) used his immense talent to praise Verona with his pencil and his pen. He first visited the city in 1835 and then he returned many times, in 1841, in 1846, in 1849, in 1869, and every visit was for him an occasion to study with painstaking accuracy and loving dedication a particular monument or palazzo, or church: Arche Scaligere, Piazza dei Signori, Piazza Erbe, Sant’Anastasia. For the artist who understood the greatness of the stones of Venice, Verona was nonetheless “exquisite”. Charles Dickens (1812-1870) went on his Grand Tour in 1844-45. He was afraid that the real Verona would disappoint him, instead everything reminded him of Romeo and Juliet. “Pleasant Verona!” For its old, noble palazzi and for its enviable position: the most beautiful city in Italy. Robert Browning (1812-1889) and Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-1861), both visited Verona, but did not include remembrances in their poems. Elizabeth, though, compares the Italian nation of the Risorgimento, captive of the Austrian Empire, to the unfortunate Juliet: “Juliet of Nations”. Sir Frederick Leighton (1830-1896), painter, friend of the Brownings, he came to Verona in 1852. He describes it vividly in his diaries. In 1853 he painted “The reconciliation of the Montagues and Capulets after the death of Romeo and Juliet” and, with a clear allusion to the Italian situation, in 1864, he completed an imposing picture of “Dante in exile”. AMERICAN TRAVELLERS Charles Eliot Norton (1827-1908), scholar, polymath, particularly interested in Italian culture, he completed a very successful prose translation of the Divine Comedy. He corresponded with John Ruskin with whom he exchanged views on the attractions of Verona. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882), poet, deeply steeped in European culture, translator of Dante, sympathetic to the Italian cause, he was in Verona with his daughter on June 13, 1869. He saw John Ruskin who was sketching in Piazza dei Signori. He approached him and then they all went for a stroll. William Dean Howells (1837-1920) American Consul in Venice, effective and talented writer of novels and of his Italian experience, in 1867 he published his Italian Journeys, where he narrates the wonderful discovery of the ruins of the Roman Theatre. Henry James (1843-1916) was in Verona in 1870, coming from Munich which, compared to the Italian city, he found ugly. He walked all around the city and, at the end of his visit, he declared that it was enough to stay in Verona to acquire a classical education. “Nowhere else is such wealth of artistic achievement crowded in so narrow a space; nowhere else are the daily comings and goings of men blessed by the presence of manlier art.” Edith Wharton (1862-1937) came to Italy almost every year after her marriage to Teddy in 1885. She was completely captivated by the landscape around Lake Garda. She actually used this setting for the very romantic escape of the lovers in her first novel, The Valley of Decision (1902), which deals with the situation of the Italian states just before the advent of Napoleon. Ezra Pound (1885-1972) in 1910 wrote to his parents that Verona was probably the most beautiful city in Northern Italy, that the church of San Zeno represented architectural perfection and that, if there was a heaven on earth, that was to be found in Sirmione on Lake Garda. OSCAR WILDE’S CONTEMPORARIES George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans, 1819-1880), the genial novelist of Middlemarch and Romola, visited Verona with her husband John Cross, who was twenty years her junior, in 1880, just after their wedding. The couple, enjoying their honeymoon, found the city picturesque and endearing and they had some innocent fun imitating Dante and Beatrice and Romeo and Juliet. John Addington Symonds (1840-1893) preferred to live in Italy for its mild climate and because everything reminded him of the historical period that he loved and studied, the Renaissance. With the vigil eye of the trained aesthete he visited many cities in the North of Italy, such as Venice, Verona, Milan, narrated their history and described their treasures in The Renaissance in Italy (7 vols. 1875-1886), which after Walter Pater’s epoch-making oeuvre, became a classic. Wilde, who had carefully read Symonds, found some descriptions invaluable for the composition of his novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891). Arthur Symons (1865-1945), writer, critic of the Decadent movement in England, knowledgeable about all things Italian, in accordance with his fin de siècle sensibility, he said that he preferred Mantua, in particular the ruins of the Gonzaga castle, to splendid Verona. When he arrived in Verona on May 6, 1894, he spent a lovely morning in a beautiful garden (Giardino Giusti?); but, just the same, he considered Verona too perfect, too smart, unreal. Herbert Horne (1864-1916) was a poet, biographer and sharp critic of Sandro Botticelli and his philosophical paintings. In 1894, after a chance meeting with Henry James in Venice, he decided to accompany Arthur Symons to Mantua and Verona. Both would have liked to stay on in Italy and in Verona they started thinking of buying a palazzo, possibly in Venice. Horne actually realized his dream because he went to live in Florence in 1912. He became a very active collector of antiques and paintings and when he died he left his palazzo with all its precious collections to the city of Florence, the present Museo Horne. AFTER WILDE Israel Zangwill (1864-1926) was in Italy with his wife Edith. On February 21, 1909 they were both in Mantua and, shortly after, they arrived in Verona. In 1910 Zangwill published his travel narrative, Italian Fantasies, which reproduced on the book cover the “Madonna of the rosewood” , painted by Stefano da Zevio and on display at the Castelvecchio Museum in Verona. Walking around town he admired San Zeno with its bronze portals, the Museum of Natural Science, the great palaces, of which he particularly appreciated Palazzo Canossa, which he toured with its owner. Zangwill also reminds us that Dante mentions his exile in Canto XVII, v. 58 of Paradise in his Comedy, as if Verona could only be mentioned in heaven. Alethea Wiel, aware of the continuous interest that the city held for the English traveller, published The Story of Verona, London, Dent, 1907. Nora Duff, stayed in Mantua then in Verona where she was in touch with the Marquis Luigi Canossa for her scholarly work on the great Countess Matilda of Canossa, which she published with the title, Matilda of Tuscany, la gran donna d’Italia, London, Methuen, 1910. Alice Maude Allen published A History of Verona, London, Methuen, 1910. David Herbert Lawrence (1885-1937) in 1912 he was in Verona with Frieda who, exhausted from a long walk through the city, went to sit at the base of Dante’s statue in the Piazza dei Signori. In 1929 the couple returned to Verona, but David, who was very ill, instead of enjoying the sights, dedicated himself to revising the poem, filled with forebodings of death, Bavarian Gentians. David and Frieda lived on the shores of Lake Garda from 1912 to 1913. In that period, at Gargnano, Lawrence wrote the preface to Sons and Lovers, and he also composed a series of seven literary sketches dedicated to the genius loci, the spirit of place. Like Wilde, he also attended a very lively performance of Hamlet, with Enrico Persevalli in the role of the protagonist. James Joyce (1882-1941) was invited by Ezra Pound to visit him in Sirmione in 1920, when, undergoing a period of great economic difficulty, he was, besides his regular job as a teacher, dedicating himself to the writing of Ulysses (1922) He was at the time actually revising the episode of Nausicaa. Joyce met Pound on June 8th and the American poet, who also noticed that his friend was not in good health, tried to convince him to go and live near him in Sirmione. GUIDES Travellers in general relied on guides in order to visit the city according to their own pace. This meant that at times they could find an expert available who would show them all the main sights, a cicerone, or, as was more often the case in the nineteenth century, they could stroll through the centre of the city or take a carriage and admire the most important monuments by reading all the information packed in their very scholarly guides, books that specialized in detailed descriptions of everything that could be of any interest or use for the tourist. There was a rather varied choice of English and Italian guides. For instance, John Ruskin’s tour of Verona in 1846 was clearly organized by consulting his Murray, a guidebook edited by Sir Francis Palgrave in 1842, whose authority the art critic directly quoted concerning the church of San Zeno. The Handbook for Travellers in Northern Italy: States of Sardinia, Lombardy and Venice, Parma and Piacenza, Modena, Lucca, Massa-Carrara, and Tuscany, as far as Val d’Arno became an indispensable travelling aid for the Victorian tourist in Northern Italy. Charles Dickens, during his Italian Grand Tour in 1844-45 was often bored by Palgrave’s pedantic style and often went off to visit a town without the assistance of his vade-mecum. When Dickens arrives in Verona he thinks that the best thing to do is to go directly to Juliet’s house and then to walk to Juliet’s tomb, which is simply an empty, marble trough, and to meditate on her unfortunate fate. Once back in his hotel room, Dickens in a facetious mood, tells his readers that he will read Shakespeare’s play like no one has ever done before in Verona. There were other means that inspired travellers to travel abroad. Printed illustrations, in many cases, were largely responsible for enticing people to face the hardships of a long trip. Quite famous were the printed drawings of the main sights of Verona by Samuel Prout. And, of course, travel diaries, narratives, chronicles, memoirs and the many accounts of the Grand Tour that circulated from the eighteenth century onwards, offered a great deal of information and encouraged a trips abroad in order to broaden the mind and learn the principal rules of social living. Literature also dealt a great deal with travel. Ruskin’s generation was influenced in a very positive way by Byron’s poems, in particular by Childe Harold’s Pilgimage (1809-18, the fourth Canto is entirely dedicated to Italy) and by Samuel Rogers’ Italy (1822).