Urban 4-H Programs - National Association of Extension 4

advertisement

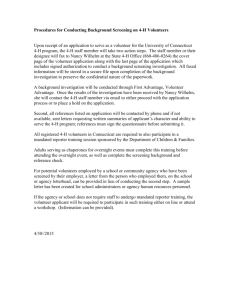

Urban 4-H Programs Urban Task Force, Programs Committee NAE4-HA For over 50 years, urban 4-H has been an emerging focus of the Cooperative Extension Service. Much of the initial work was a result of the 1965 Civil Rights legislation and the “War on Poverty”. In the mid to late1960’s, urban 4-H worked through EFNEP programs and instructional television programs such as Mulligan Stew. These programs delivered specific information to targeted audiences of disadvantaged youth and minorities1. National workshops were held for professionals to address the needs of minority youth, and the Extension Committee on Organization and Policy encouraged the participation of minorities in national 4-H activities. What is Urban Programming The “urban” designation used by the Census Bureau for urbanized area and urban clusters includes “all territory, population and housing units in urban areas, which include urbanized areas and urban clusters. An urban area generally consists of a large central place and adjacent densely settled census blocks that together have a total population of at least 2,500 for urban clusters, or at least 50,000 for urbanized areas. Urban classification cuts across other hierarchies and can be in metropolitan or non-metropolitan areas.”2 Other sources define the "urban" category as those areas classified as being urbanized (having a population density of at least 1,000 persons per square mile and a total population of at least 50,000).3 While Extension Urban Programs may not have a precise definition, it is possible to use the previously mentioned definitions as a guide. Historical Perspective of Urban 4-H Urban Extension 4-H Programs were studied in the 1970’s, with eight urban 4-H programs extensively documented in a national survey completed by Joseph Brownell.4 In the thirtycity study, Brownell sought comprehensive 4-H programming models for replication in other urban settings. Noting a lack of administrative programming commitment and financial support, he found that most urban 4-H agents (called Directors) had carved out strong programs unique to the individual urban setting. During the years of the 1970’s and 80’s, 4-H membership continued to grow, reaching maximum numbers due to the success of the Mulligan Stew program and the additional of delivery systems in school age child care, collaborative programming, and a focus on literacy. 4-H, in particular, struggled with serving minority youth, an observation stated very strongly as part of the Evaluation of Economic and Social Consequences of Cooperative Extension Programs5 published by the United States Department of Agriculture. With the charge that 4-H had not extended its programs adequately to the disadvantaged and minorities, a renewed effort was made to overcome what appeared to be a pattern of discrimination. The Cooperative Extension System turned its attention to Youth At Risk programming in 1988. The National Association of Extension 4-H Agents created a Programs subcommittee for Urban Programs in the mid 1980s that created learning experiences for urban 4-H staff through national seminars, newsletters, and idea exchanges instituted at regional urban Extension conferences in the 1990s. 1 In the early 1990s, Extension internally debated the rationale for urban programs, possibly stemming from a perception of resources being reallocated from agricultural programs6. Others charged that urban programs were nothing more than just a way to provide social services to the poor and minorities; a service that was not in the mission of Extension. Several states moved to the hiring of “urban” staff, with special training in media, technology, and collaborations. Studies about the challenges, staffing patterns, and unique educational delivery methods of urban staff and programs resulted in a call for greater understanding of Extension effectiveness in urban settings7,8. Renewed Interest by 4-H Agents in 2005 The 2005 National Association of Extension 4H Agents meeting found a new interest in the needs of urban staff to communicate about common programs and concerns. With over sixty professionals present, state and county faculty again renewed their interest in sharing effective, quality programs, and in accountability for those programs. In 2006, a NAE4-HA Urban Programs Committee survey was completed that encouraged urban 4-H staff to share their ideas in a Directory of Successful Urban 4-H Programs. This Directory will continue to grow annually through the addition of new programs, reviewed by peers, allowing professionals across the nation to read and learn about the best programs. There is not a specific model for urban 4-H programs, since most delivery models fall along a continuum, just as those used in other locations. Across the nation, research continues to show that the impact of 4-H delivery is very dependent upon the ability of Extension faculty to maximize structured learning environments, with caring support of volunteers, and the mastery of subjects. Many studies have shown that urban 4-H programs are effective in teaching problem solving, life-skills, and providing positive experiences for youth (as an alternative to gangs), without sacrificing essential elements9,10. Some research based differences between rural and urban are found in methods of recruitment, volunteer incentives, use of media, targeted audiences, and site-based programs11,12. What We Know About Urban 4-H Programs The following observations about urban 4-H programming come from experience and reflection of several 4-H faculty as they work in urban programs. All deserve discussion, debate, and evaluation. Program Sites Urban 4-H programs often target audiences where they live in high-need, low-resource locations, e.g., after-school classrooms, community youth centers, housing developments, schools, and churches. These locations provide a safe haven for already existing groups of youth to learn and play together. Additional youth in the same community are encouraged to join in the activities. Safety and risk management, important concerns in urban environments, may be more easily contained. Close proximity to targeted neighborhoods also eliminates the problems of transportation. Sometimes the use of in-tact or pre-existing groups, allows the staff to focus on the educational delivery rather than group start-up and maintenance. Long term, sustained programs such as clubs are often very effective at local sites and the sites, in turn, become a safe haven for youth. Collaborations / Partnerships In urban environments, working through and with existing citywide and neighborhood groups provides an excellent opportunity to partner. Using the best practices of positive youth development, urban 4-H staff often collaborate with others interested in making a difference, creating new innovative curricular experiences or packaging existing curriculum to be taught by youth professionals, teachers, or volunteers. Based on the expressed need of the community, these programs may be based in academics, lifeskill development, or mastery of career building subjects. Some very large funded programs 2 allow for greater flexibility and the creation of innovative issue based programs. Site coordinators for after-school programs in Lincoln, Nebraska highly value 4-H curriculum materials. They benefit from extension staff training their teachers to use the curriculum. The research-based curriculum saves development time, provides hands-on learning and facilitates effective use of limited after-school resources. 13 In another example of quality collaborations, the University of Tennessee Extension in Nashville/Davidson County, seeing a need for career related educational programming, partnered with the Metropolitan Nashville Board of Parks and Recreation. Paid Extension staff members trained teen leaders (receiving a small stipend) and adult Parks and Recreation staff members to implement the 4-H WORKS career education program to middle school. Youth from basically all geographic areas of Nashville had access to this program as it was implement in the Parks and Recreation community centers which are strategically located in highly populated areas of the city.14 Collaborative efforts take additional time to develop and maintain, often providing greater clout in fundraising and marketing. Partnership sponsored programs can take advantage of the best of several organizations, and provide excellent opportunities for innovative and highly visible programs. Although competition for “credit” or “identity” can be an issue, relationship building and formal agreements can hasten a positive environment. Today’s youth are identified as the millennial generation. This generation is growing up with technology. It is integrated into their educational experiences, daily lives and social networks. Extension staff must acknowledge these trends and embrace this changing culture. Technology savvy 4-H youth should be viewed as valuable skilled resources and contributors to the 4-H program. In addition, Extension offices must expand their modes of outreach by using technology. This is equally important in both urban and rural areas. Using educational technology, such as “horseless clubs” and “egg cam” available on http://lancaster.unl.edu, are examples of how 4-H can use technology to reach youth at home or in the classroom.15 Staffing of Professionals and Volunteers Increasing calls for more staff in urban areas are found in many strategic plans for Extension. In some studies, the program areas of 4-H and horticulture are most often seen as areas of expansion for urban programs. In the most urban programs, there are a mix of three or more diverse professionals, program assistants, paid part time help (often youth or stipend volunteers), and a complex management plan for volunteers. It is not uncommon for urban 4H programs to be fortified through grants and foundations. Staff are engaged in the normal leadership of a 4-H program, although there often is a very distinct division of labor. Program Assistants or part time employees are employed to perform a specific function, e.g., youth community forums, project specific classroom training, school enrichment, or volunteer recruitment and support. Paid staff often train the staff of other youth serving organizations to insure the use of youth development essential elements. There is a great deal of turnover of agency youth workers, teachers, park/recreation center staff . Some urban offices have also specialized in the adult/youth partnership training of both internal and external volunteer boards, councils, and committees. In some urban offices, although not all, there is a greater reliance on internal paid staff to work events and activities. Unless there is a specified volunteer recruitment coordinator, finding volunteers to handle the many events and activities at the county or district level is difficult. It should be noted that large populations create a wider potential pool of resource leaders and greater access to professionals who are willing to give small blocks of time (episodic volunteers). Volunteers can be found in large urban cities, but it requires greater effort, training modifications (reference 3 sheets, weekends, nights) and more support of the volunteer relationship. the media, often one or two well-coached youth are showcased. Administrators may underestimate the loyalty of urban volunteers and youth, but usually when put to the test, loyalty is very strong. Integration into General 4-H Programs Urban 4-H club programs may need to use a systems approach and be very structured processes involving mass distribution of training materials, monthly club activities, master calendars, and recognition programs. Program assistants may be assigned to support club programs at a variety of sites. The projects studied may be more group and experience oriented. Club structures may be more disconnected from a county program and there is less youth participation with county, district, and state activities. Recognition programs may focus more on local participation, progress toward goals, and cooperative learning, while standards of excellence and competition may be de-emphasized. Subject Matter The 4-H topics taught in urban areas vary with the expertise of the staff, school needs, and grant driven topics. Often there are one or more topics that reflect strong ties to agriculture within 4-H (embryology, gardening, ag-in-theclassroom, to name a few). Subject matter training for youth is often packaged through classroom modules (teacher guides, lesson plans, etc.) checked out to trained volunteers, teachers, or taught by a paraprofessional or professional staff member. Other times, classrooms or agencies may come to a central location as part of series of rotations and handson activities , e.g., farm/city days. In most situations, 4-H curricular materials have been correlated to the state school standards for classroom instruction. The use of school classrooms provides a positive way to engage large numbers of diverse youth in quality youth education in partnership with schools. Marketing and Visibility The intensity of media stimulation and its focus on quick volatile events, creates a difficult situation for obtaining coverage of the positive impact of a 4-H program. Major stories are likely to focus on problems or critical issues, and it takes strong relationships with media personnel to get coverage. For most Extension professionals, it is important to control the level and quantity of information furnished to the media, due to the volume of response that can occur as a result of an offer. Media attention, when obtained, generates more demand than can be handled. Messages often are credited to wrong sources or personnel, and sources are mislabeled. When presenting programs via volunteers or youth to Because of the availability of more youth, urban programs can provide teen programming opportunities on a larger scale. This is particularly true if teens are employed to reach more teens. Team or group activities such as judging teams are attractive to urban youth, particularly urban homeschool members. Urban programs often struggle to involve parents. Youth agencies, after-school centers, and community centers provide a safe location for youth to stay in non-school hours. The cost of living may be higher in some urban areas, and low-income parents may be working two or more jobs to make ends meet. Some parents have less time to devote to volunteer efforts. For Home School Coops, 4-H programs offer quality projects and experiences that provide socialization and opportunities to be involved in democratic experiences. Their sites in urban areas are larger and function well for 4-H programming needs. Summary Urban 4-H programs are here to stay and will only grow stronger with increased knowledge of effective delivery methods. We can learn from the experiences of the urban 4-H youth 4 development professional. Their programs are marked by unique approaches to program sites, staffing, subject matter study, marketing, and integration into Extension offerings. We salute those who are most successful and anticipate learning more about quality urban 4-H programs throughout the nation. Contributions to this paper were made by: Gary Bergman Justin Crowe Nia Imani Grant Marilyn Norman 1 History of 4-H, USDA 4-H Headquarters, 4-H Centennial Web site 2 Definition of Urban, US Census, http://www.census.gov/ 2007 Communities, Journal of Extension, Volume 42 Number 1, 2004 12 Fritz, Susan, D. Karmazin, J. Barbuto, Jr., S. Burrow, Urban and Rural 4-H Adult Volunteer Leaders' Preferred Forms of Recognition and Motivation, Journal of Extension, Volume 41 Number 3, 2003. 13 Found in the NAE4-HA National Directory of Successful Urban Programs, http://www.colorado4h.org/urbanprogram/ 2007. 14 4-H Works, University of Tennessee Extension , Metropolitan Nashville/Davidson County, 2007. 15 UNL Extension in Lancaster County, 4-H Youth Development Programs, University of Nebraska website: http://lancaster.unl.edu, , 2007. 3 State of Georgia Office of Planning and Budget, Census Data Program, http://www.gadata.org/information_services/Census_Info/ KEY%20TERMS%20MSA.htm 2007. 4 Brownell, Joseph C., A Study of Urban 4-H Club Programs in Thirty Cities of the United States. ERIC #: ED064617, 1971. 5 Evaluation of Economic and Social Consequences of Cooperative Extension Programs, Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 1980. 6 Panshin, Dan, Overcoming Rural-Urban Polarization, Journal of Extension, Volume 30 Number 2, Summer, 1992. 7 Fehlis, Chester P., Urban Extension Programs, Journal of Extension, Volume 30 Number 2 Summer, 1992. 8 Van Horn, Beth E., Changes and Challenges in 4-H (Part 1), Journal of Extension, Volume 37 Number 1, February 1999. 9 Van Horn, Beth E., Changes and Challenges in 4-H (Part 2), Journal of Extension, Volume 37 Number 1, February 1999. 10 Fleming-McCormick, Treseen; Tushnet, Naida C. Does an Urban 4-H Program Make Differences in the Lives of Children? ERIC #: ED405408, 2001 11 Skuza, Jennifer A., 4-H Site-Based Youth Development Programs: Reaching Underserved Youth in Targeted 5