Group B streptococcus (GBS), is the gram positive

advertisement

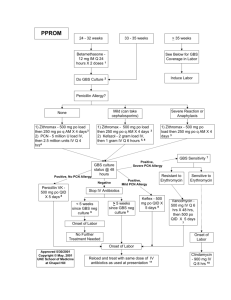

Introduction Group B streptococcus (GBS), is the gram positive aerobic diplococcus Streptococcus agalactiae, and is found in pairs or in chains. The bacterium is encapsulated in a polysaccharide coating. The Lancefield classification system distinguishes different streptococci by the specific carbohydrate antigen; GBS has Lancefield group B antigen. There are nine serotypes of GBS; in the United States, serotype Ia, Ib, II, III, and V account for approximately 95% of all cases. Serotype III is most prevalent in early-onset meningitis and late-onset disease in neonates. Early onset disease is defined by infection at > 7 days of life, and late-onset disease from 7 days to 3 months. Approximately 80% of early–onset is due to vertical transmission from mother to infant during labor, and usually presents as sepsis and pneumonia within the first 24 hours, with 5 – 10% of cases presenting as meningitis. Approximately 10 – 30% of pregnant women are colonized with GBS. Risk factors for colonization during pregnancy include diabetes, age < 20 years, less than four pregnancies, African-American or Hispanic ethnicity, and low maternal serum antibody specific to GBS serotype. Obstetric risk factors include intrapartum fever, prolonged rupture of membranes, GBS bacteriuria, previous infant affected by GBS disease, and delivery < 37 weeks gestation. In GBS culture positive women, the mean rate of transmission risk is 50%, with a range of 29% to 85%. Of those infants who become colonized, 1-4 Background In the 1970s, GBS was identified as the leading cause of neonatal sepsis, with approximately 7500 cases per year prior to recommended prevention protocols.5 Neonatal mortality rates were reported as high as 50%, with annual cost approaching $300 million. Morbidity from this disease included blindness, hearing loss, mental retardation, and cerebral palsy. 3,6 With studies in the late 1970s and 1980s demonstrating the effectiveness of intrapartum antibiotic regimens in decreasing neonatal cases,7-9 in the United States, similar guidelines were proposed by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) in 1992, followed by guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 10-12 The 1996 CDC guidelines offered two strategies, one a risk based approach, the other a screen based approach using cultures; these were endorsed by the AAP and ACOG. Risk Based Screening versus Culture Based Screening The risk based strategy recommended chemoprophylaxis for intrapartum risk factors associated with early-onset disease: delivery at < 37 weeks gestation, an intrapartum maternal temperature of 100.4 F (38.0 C), or rupture of membranes 18 hours. The screen based strategy promoted universal screening of all pregnant women between the 35 – 37 weeks gestation with vaginal and rectal swabs for GBS colonization, with colonized women receiving antibiotics intrapartum. Under both strategies, women with GBS bacteriuria or a history of a previous infant with early onset GBS disease were also to receive intrapartum antibiotic therapy. The effect of the guidelines resulted in more hospital drafting formal policies for antibiotic use, noting a change in the incidence of early onset disease in those institutions with policies, and increased provider use of one or both strategies.13-16 With these changes, the incidence of both early-onset and late-onset GBS disease continued to decline, from an 1.7 cases per 1000 live births in 1993 to 0.45 cases per 1000 live births in 1999.16,17 However, based on surveillance of several areas in the US, these recommendations were revised in 2002.18 A summary of these differences include: 1) Universal culture based screening for vaginal and rectal GBS colonization of all pregnant women between 35 – 37 weeks gestation 2) An update for prophylaxis regimens for penicillin allergic women, with women stratified into 3 groups: a) women not at high risk for anaphylaxis receiving cefazolin b) women at high risk for anaphylaxis with GBS susceptible to clindamycin or erythromycin receiving these antibiotics c) women at high risk for anaphylaxis with GBS resistant to clindamycin or erythromycin, or unknown sensitivities receiving vancomycin 3) GBS colonized women undergoing elective cesarean sections without rupture of membranes or labor are recommended to not receive antibiotic prophylaxis 4) A proposed algorithm for managing patients with threatened preterm labor, with the recognition that there may be appropriate alternatives a) GBS negative women do not need antibiotic prophylaxis b) GBS carriers should receive IV penicillin for hours, to be continued for > 48 hours at the discretion of the physician; antibiotics to be restarted when the patient is in labor c) Women without culture results should under vaginal/rectal cultures, and be started on antibiotics. If cultures are negative, the antibiotics should be stopped; if the cultures are positive, recommendations under 4b should be followed 5) Detailed instructions on the appropriate technique for obtaining cultures, appropriate transport and culturing methods including the use of selective medias to enhance isolation of GBS, and susceptibility testing with other antibiotics for patients who are penicillin allergic 6) An updated algorithm for the management of newborns exposed to antibiotic prophylaxis The guidelines also stress that many recommendations are unchanged: 1) Penicillin is the first line agent, while ampicillin is an acceptable alternative 2) Women with unknown culture results in labor should be managed according to the risk based strategy 3) Women with vaginal and rectal cultures negative for GBS colonization do not need antibiotic prophylaxis even if obstetrical risk factors develop 4) GBS bacteriuria in the current pregnancy or a history of a previous child with GBS disease should receive intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis 5) With the exception of GBS bacteriuria, asymptomatic colonization should be treated only intrapartum Although the CDC acknowledges that both risk and culture based strategies worked to reduce early-onset disease, this shift to a culture based strategy is based series of studies, including a study by Schrag et al reporting a direct comparison of both strategies and controlling for risk factors.18,19 Schrag and colleagues reviewed > 5100 deliveries from a surveillance area containing > 600,000 deliveries between 1998 and 1999. They noted 312 cases of early onset disease, or an incidence rate of 0.5 cases per 1000 live births. Of these infected infants, 62% did not have clinical risk factors. Similarly, 18% of women with positive GBS cultures also did not have clinical risk factors. For this group, women who didn’t receive antibiotics had an incidence rate of 1.3 cases per 1000 live births. When compared to rate of 5.1 cases per 1000 live births in the era prior to prevention, the efficacy of preventing early onset GBS is 88%. They also noted that 89% of women in the screened protocol who had indications for intrapartum antibiotics received intrapartum antibiotics, compared to only 61% of women in the risk based protocol receiving antibiotics despite having a risk factor. In summary, their data demonstrates that more patients in a culture based strategy received antibiotics than those with risk factors, and that the culture based approach captured more patients at risk by identifying those women who were colonized but without risk factors. Consequences of the Revised CDC Guidelines: Concerns for Adverse Reactions to Antibiotics, Emergence of Resistant GBS, and Rise of Non-GBS Pathogens While minor reactions can occur as high as 10%, anaphylaxis is a rare event, estimated incidence of 4 per 10,000 – 100,000. With its use intrapartum, anaphylaxis can be addressed in a rapid fashion, and its risk is outweighed by the risk of neonatal GBS disease. 19 At this time, there have no reports of GBS resistant to penicillin or ampicillin. There reports, however, of erythromycin and/or clindamycin resistant GBS, with ranges of 7 – 25% resistance to erythromycin, and 3 – 15% for clindamycin. While it is recommended that penicillin sensitive GBS should be considered sensitive to the first generation cephalosporin cefazolin, there also a report of resistance to the second generation cephalosporin cefoxitin. Another concern with the implementation of antibiotic use to combat GBS disease is the concern for the emergence of antibiotic resistance in other organisms responsible for neonatal sepsis. While some studies have suggested no increase non-GBS organisms causing neonatal disease, others have suggested that there are increases in vaginal flora with resistant organisms, leading to increased exposure to neonates. Others have suggested caution in interpreting resistance information, but all are in agreement that continued surveillance is imperative. 18-28 Future Goals Work by Yancey et al demonstrated that GBS cultures taken 1 – 5 weeks prior to delivery, starting at 35 – 36 weeks gestation had a positive predictive value of 88%; at 6 weeks or greater, positive antenatal cultures were only 43% positive at the time of delivery. However, a more recent study noted only a 67% positive predictive value. 23,28 This has led to research to pursue rapid GBS testing to further target the at risk population. Ultimately, vaccination is seen as the next advance. However, a vaccination also has concerns to address, such as vaccine duration, distribution and implementation to the population, and continued surveillance to monitor for changes in serotypes within a population. 18 References 1 Platt JS, O’Brien WF. Group B Streptococcus: Prevention of early-onset neonatal sepsis. Obstet Gynecol Survey 2003;58:191-6 2 Schuchat A. Epidemiology of group B streptococcal disease in the United States: Shifting paradigms. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 1998; 11: 497-513 3 Edwards MS, Baker CJ. Group B Streptococcal Infections. In: Remington JS, Klein JO, eds. Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn Infant, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2001:1091-1156 4 American Academy of Pediatrics. Group B Streptococcal Infections. In: Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2003 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 26th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL:584-91 5 Zangwill KM, Schuchat A, Wenger JD. Group B streptococcal disease in the United States, 1990: Report from a multistate active surveillance system. MMWR 1992; 41:2532 6 Invasive group B streptococcal disease (GBS) – technical information. In www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dbmd/diseaseinfo/groupbstrep_t.htm 7 Yow MD, Mason EO, Leeds LJ, Thompson PK, Clark DJ, Gardner SE. Ampicillin prevents intrapartum transmission of group B streptococcus 8 Easmon CSF, Hasting MJG, Deeley J et al. The effect of intrapartum chemoprophylaxis on the vertical transmission of group B streptococci. Br J Obstet Gynecol 1983;90:633-5 9 Boyer KM, Gotoff SP. Prevention of early-onset neonatal group B streptococcal disease with selective intrapartum chemoprophylaxis. N Engl J Med 1986;314:1665-9 10 American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases and Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Guidelines for prevention of group B streptococcal (GBS) by chemoprophylaxis. Pediatrics 1992;90:775-8 11 Group B streptococcal infections in pregnancy. Technical Bulletin #170, 1992. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Washington DC. 12 CDC. Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease: a public health perspective. MMWR 1996; 45:1-24 13 Adoption of hospital policies for prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease--United States, 1997. MMWR 1998;47:665-70 14 Hospital-based policies for prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease – United States, 1999. MMWR 2000;49:936-40 15 Factor SH, Whitney CG, Zywicki SS, Schuchat A. Effects of hospital policies based on 1996 group B streptococcal disease consensus guidelines. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95:377-82 16 Watt JP, Schuchat A, Erickson K, Honig JE, Gibbs R, Schulkin J. Obstet Gynecol 2001;98:7-13 17 Schrag SJ, Zywicki S, Farley MM, Reingold AL, Harrison LH, Lefkowitz LB, Hadler JL, Danila R, Cieslak PR, Schuchat A. Group B Streptococcal Disease in the Era of Intrapartum Antibiotic Prophylaxis New Engl J Med 2000; 342: 15-20 18 Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease: revised guidelines from CDC. MMWR 2002;51:1 - 25 19 Schrag SJ, Zell ER, Lynfield R, Roome A, Arnold KE, Craig AS, Harrison LH, Reingold A, Stefonek K, Smith G, Gamble M, Schuchat A. A population-based comparison of strategies to prevent early-onset group B streptococcal disease in neonates. N Engl J Med 2002;347:233 - 9 20 Baltimore RS, Huie SM, Meek JI, Schuchat A, O'Brien KL. Early-onset neonatal sepsis in the era of group B streptococcal prevention. Pediatrics 2001;108:1094 - 98 21 Towers CV, and Briggs GG. Antepartum use of antibiotics and early-onset neonatal sepsis: the next 4 years. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;187:495 - 500 22 K.T. Chen, R.E. Tuomala, A.P. Cohen, E.C. Eichenwald and E. Lieberman, No increase in rates of early-onset neonatal sepsis by non-group B streptococcus or ampicillin-resistant organisms. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001;185:854 - 58 23 Edwards RK, Clark P, Duff P. Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis 2: positive predictive value of antenatal group B streptococci cultures and antibiotic susceptibility of clinical isolates. Obstet Gynecol 2002;100:540 - 4 24 Edwards RK, Clark P, Sistrom CL, Duff P. Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis 1: relative effects of recommended antibiotics on gram-negative pathogens. Obstet Gynecol 2002;100:534 - 9 25 Manning SD, Foxman B, Pierson CL, Tallman P, Baker CJ, Pearlman MD. Correlates of antibiotic-resistant group B streptococcus isolated from pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol 2003;101:74 - 9 26 Spaetgens R, DeBella K, Ma D, Robertson S, Mucenski M, Davies HD. Perinatal antibiotic usage and changes in colonization and resistance rates of group B streptococcus and other pathogens. Obstet Gynecol 2002;100:525 - 33 27 Stoll BJ, Hansen N, Fanaroff AA, Wright LL, Carlo WA, Ehrenkranz RA, Lemons JA, Donovan EF, Stark AR, Tyson JE, Oh W, Bauer CR, Korones SB, Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Stevenson DK, Papile LA, Poole WK. Changes in pathogens causing earlyonset sepsis in very-low-birth-weight infants. N Engl J Med 2002;347:240 - 7 28 Moore MR. Schrag SJ. Schuchat A. Effects of intrapartum antimicrobial prophylaxis for prevention of group-B-streptococcal disease on the incidence and ecology of earlyonset neonatal sepsis. Lancet Infec Dis 2003;3:201 – 13 29 Yancey MK, Schuchat A, Brown LK, Ventura VL, Markenson GR. The accuracy of late antenatal screening cultures in predicting genital group B streptococcal colonization at delivery. Obstet Gynecol 1996;88:811-5