Ahrens_12252_ed

advertisement

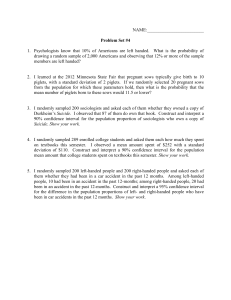

16th IFOAM Organic World Congress, Modena, Italy, June 16-20, 2008 Archived at http://orgprints.org/view/projects/conference.html Prolonged suckling period in organic piglet production – effects on selected immunological parameters Ahrens, F.1, Pollmüller, T.2, Sünkel, Y.3, Bussemas, R.4, Weissmann, F.5 & Erhard, M. H.6 Key words: Organic piglet production, prolonged suckling period, weaning age, immune system Abstract During weaning, piglets are under strain from the loss of their dam, the change in feed, and a new microbiological environment. How much this strain influences the piglets depends mostly on their immune system. Piglets from organic production are weaned later (at least 40 days) than piglets from conventional rearing, but the performance and health status of organic piglets are often not satisfying. Therefore, it was the aim to investigate whether a prolonged suckling period of 63 days results in better immune status of piglets than with weaning at day 42. To answer that question we vaccinated piglets at different times with a “known” (by vaccination of dam) and an “unknown” antigen and analysed the plasma for immunoglobulin G (IgG) concentration and the antigen-specific IgG antibodies by ELISA. Two farrowing cycles of 36 sows were recorded. Time of vaccination did not influence IgG concentration. In contrast, early weaned piglets showed a higher IgG concentration on day 49 than late weaned piglets. During the first farrowing cycle a significant immune response against both antigens was present in piglets vaccinated on day 42. Such a response was not found in piglets vaccinated on day 63 and in piglets of the second farrowing cycle. In conclusion, the results did not show an improved immune status of piglets undergoing a suckling period of 63 days. Introduction Organic piglet production is often characterized by poorer performance compared with conventional reared piglets. Whereas the number of piglets born alive is the same, the number of reared piglets is definitely too low (Löser, 2007). Weaning challenges piglets in many different ways. How much the different strains influence the health status of the piglets depends mostly on the immune system. Passive immunity, firstl established by immunoglobulin transfer by colostral milk from the sow to the piglets, decreases in the piglet as long as the production of endogenous immunoglobulin is at 1 Chair of Animal Welfare, Ethology, Animal Hygiene, and Animal Housing, Department of Veterinary Science, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Schwere-Reiter-Str. 9, 80637 Munich, Germany, E-Mail f.ahrens@lmu.de 2 As Above 3 As Above 4 Institute of Organic Farming, Federal Agricultural Research Centre, Trenthorst, 23847 Westerau, Germany 5 6 As Above Chair of Animal Welfare, Ethology, Animal Hygiene, and Animal Housing, Department of Veterinary Science, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Schwere-Reiter-Str. 9, 80637 Munich, Germany 16th IFOAM Organic World Congress, Modena, Italy, June 16-20, 2008 Archived at http://orgprints.org/view/projects/conference.html the beginning. This leads to an “immunological gap” between day 20 and day 40 (Lang, 2004). Even if piglets from organic production have a longer suckling period (at least 40 days, minimum requirement of the EEC Regulation 2092/91) than piglets from conventional rearing, the “immunological gap” still seems to be present in those piglets, leading to the described consequences in performance and health status. Therefore, it was the aim of the present study to investigate whether a prolonged suckling period of 63 days results in better immune status of the piglets compared to weaning at day 42. The immune response to a “known” and “unknown” antigen was tested. Materials and methods The trial was performed from spring 2006 to mid 2007 at the experimental organic farm of the Institute of Organic Farming of the Federal Agricultural Research Centre in Trenthorst, Germany, in accordance with Regulation 2092/91/EEC and the IFOAM Basic Guidelines. A total of 44 sows of the genotype “Schaumann” (crossbreed of German Landrace, German Large White, and Duroc) were kept: 36 sows were used for the investigation and 8 sows were kept in reserve in a parallel farrowing rhythm in order to replace sow losses. The 36 sows were divided into 4 groups with the following treatment of the piglets: (I) early weaning and vaccination (day 42); (II) early weaning (day 42) and late vaccination (day 63); (III) late weaning (day 63) and early vaccination (day 42); (IV) late weaning and vaccination (day 63). Fourteen days after single grouped farrowing, three sows were grouped together with their respective litters and were group housed until weaning. At the weaning date the sows were removed. The weaned piglets remained in their familiar surroundings for 4 days. Then they were housed in separate indoor rearing pens in the composition of the previous suckling pig groups. Piglets were vaccinated with two antigens: avian immunoglobulin Y (IgY), which should be “unknown” for the piglets; and the “known” ovalbumin (OVA). For that antigen, maternal antibodies should exist because of a vaccination of the sows before farrowing. Secondary vaccination (Booster) was done 21 days later. Blood was sampled from eight piglets per litter on days 7, 42, 49, 63, 70, 84, and 91. Plasma was analysed for immunoglobulin G (IgG) concentration and for specific IgG antibodies against IgY and OVA by a sandwich ELISA (Erhard et al., 2001). Two farrowing cycles were recorded. Because of a significant influence of the sows on the IgG concentration of piglets on day 7, we pooled the values of the piglets for each litter. Thereafter, two-way analysis of variance with the factors “time of weaning” and “time of vaccination” was used for the statistical comparison of groups in IgG concentration, including both farrowing cycles. Specific IgG anti-OVA and IgG anti-IgY titer were compared between early and late weaned piglets separately for each farrowing cycle by Student’s t-test and MannWhitney’s rank sum test, respectively. Results Despite a higher level in the course of IgG concentration over time of late vaccinated piglets in contrast to early vaccinated piglets, vaccination itself did not seem to have any influence on the IgG concentration (Fig. 1). 16th IFOAM Organic World Congress, Modena, Italy, June 16-20, 2008 Archived at http://orgprints.org/view/projects/conference.html 18 Early Vaccination Late Vaccination IgG [mg/ml Plasma] 16 14 ** 12 10 8 ** ** 6 4 **: P < 0.01 2 n = 34 - 36 Booster Vaccination 0 7 42 49 63 70 84 91 Day of Life Figure 1: IgG levels of piglets early and late vaccinated, independent of the time of weaning. Mean ± SEM of litter means from 34 - 36 litters and eight piglets per litter. However, early weaned piglets showed a higher IgG concentration on day 49 than late weaned piglets (Fig. 2). 18 Early Weaning (Day 42) Late Weaning (Day 63) IgG [mg/ml Plasma] 16 14 12 10 ** 8 6 4 **: P < 0.01 2 n = 34 -36 0 7 42 49 63 70 84 91 Day of Life Figure 2: IgG levels of piglets early and late weaned, independent of the time of vaccination. Mean ± SEM of litter means from 34 - 36 litters and eight piglets per litter. 16th IFOAM Organic World Congress, Modena, Italy, June 16-20, 2008 Archived at http://orgprints.org/view/projects/conference.html During the first farrowing cycle a significant immune response against OVA and IgY was present in piglets vaccinated on day 42, independent of the time of weaning. Such a response was not found in piglets vaccinated on day 63 and in piglets of the second farrowing cycle (data not shown). Discussion The course in IgG levels over time of all treatment groups is congruent with data from conventionally reared piglets weaned after 21 days (Lang, 2004). The differences in the IgG values between early and late vaccinated piglets might be caused by the study design, where the allotment of sows and litters to the different treatments was oriented to the more important factor “time of weaning”. Interestingly, early weaned piglets showed a significantly higher IgG concentration on day 49. It is known that weaning increases the production of inflammatory cytokines (Pie et al., 2004), but it is postulated that weaning stress decreases the immune response (Blecha et al., 1983). Additionally, such an IgG “response” was not present in piglets after weaning at day 63. Conclusions The results of the present study did not show an improved immune status of piglets undergoing a suckling period of 63 days. However, because good performance and health status of these late weaned piglets was found by Bussemas and Weissmann (2008, in this volume), a prolonged suckling period compared to the minimum requirement of the EEC Regulation 2092/91 seems to be recommendable. Acknowledgments This work was supported by the Bundesprogramm Ökologischer Landbau, Project No. 03oe378. References Blecha F., Pollmann D. S., Nichols D. A. (1983): Weaning pigs at an early age decreases cellular immunity. J. Anim. Sci. 56:396-400. Erhard M. H., Luft C., Remler H. P., Stangassinger M. (2001): Assessment of colostral transfer and systemic availability of immunoglobulin G in new-born foals using a newly developed enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) system. J Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 85:16473. Lang E. (2004): Einfluss einer Echinacea-Fütterung auf Immunstatus und Verhalten bei Ferkeln in den ersten Lebenswochen. Doctoral Thesis, Ludwig-Maximilian-University of Munich, Germany. Löser R (2007): Gut, aber noch nicht gut genug. Bioland 4:20-21. Pie S., Lalles J. P., Blazy F., Laffitte J., Seve B., Oswald I. P. (2004): Weaning is associated with an upregulation of expression of inflammatory cytokines in the intestine of piglets. J Nutr. 134:641-647.