Abundant Grace Fellowship Church

advertisement

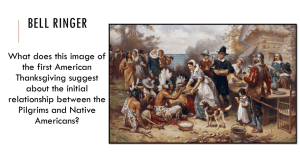

Thanking God: A 500 Year Tradition Written by the Christian Law Association Submitted with permission of CLA by Pastor J.D. Link Thanksgiving is the oldest American holiday. Although we generally attribute the First Thanksgiving to the Pilgrims in 1621, several other special times of thanksgiving preceded it on land that would eventually become part of America. In 1541 at Palo Duro Canyon, Texas, Coronado and 1,500 of his men celebrated a time of thanksgiving to God for His blessings. In 1564 at St. Augustine, Florida, French colonists also engaged in a special time of thanksgiving to God. In 1598 in El Paso, Texas, Juan de Oriate and his expedition held a similar celebration to God. In 1619 in Virginia, the Jamestown settlers held an official Thanksgiving celebration. The first Pilgrim Thanksgiving in 1621 with Samoset, Squanto, and their other Indian friends and benefactors, was not the most dramatic Pilgrim Thanksgiving. The most dramatic Thanksgiving occurred two years later. During that summer, the Pilgrims suffered a severe and extended time of drought. They knew that without a change in the weather, there would be no fall harvest. The winter would surely bring severe starvation and death to their community. Therefore, Gov. William Bradford gathered the Pilgrims together for a time of prayer and fasting. Shortly thereafter, a gentle rain began to fall. Governor Bradford explained in his History of Plymouth Plantation: [The rain] came without either wind or thunder or any violence, and by degrees in abundance, as that ye earth was thoroughly wet and soaked therewith, which did so apparently revive and quicken ye decayed corn and other fruits as was wonderful to see, and made ye Indians astonished to behold; and afterwards the Lord sent them such seasonable showers, with interchange of fair warm weather as, through His blessing, caused a fruitful and liberal harvest, to their no small comfort and rejoicing. The rain saved the corn. One of the Indians who observed this miracle remarked: Now I see that the Englishman’s God is a good God; for he hath heard you, and sent you rain, and that without such tempest and thunder as we used to have with our rain; which after our Powwowing for it, breaks down the corn; whereas your corn stands whole and good still; surely, your God is a good God. The drought had been broken; there was an abundant harvest—-cause for yet another Thanksgiving. The Pilgrim practice of designating an official time of Thanksgiving quickly spread throughout the other New England colonies as annual traditions were established of prayer and fasting in the spring, followed by prayer and thanksgiving in the fall. America’s first national Day of Thanksgiving occurred on September 25, 1789. It was the nation’s first official act set by Congress after that body completed the Constitution and Bill of Rights. According to the early equivalent of the Congressional Record: Mr. [Elias] Boudinot said he could not think of letting the session pass without offering an opportunity to all the citizens of the United States of joining with one voice in returning to Almighty God their sincere thanks for the many blessings He had poured down upon them. With this view, therefore, he would move the following resolution: Resolved, That a joint committee of both Houses be directed to wait upon the President of the United States to request that he would recommend to the people of the United States a Day of Public Thanksgiving and Prayer. . . Mr. Roger Sherman justified the practice of thanksgiving on any single event not only as a laudable one in itself but also as warranted by a number of precedents in Holy Writ. . . . This example he thought worthy of a Christian imitation on the present occasion. President George Washington heartily concurred with this request to thank Almighty God at the birth of the new Constitution. He issued the first federal Thanksgiving proclamation, declaring in part: Whereas it is the duty of all nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God, to obey His will, to be grateful for His benefits, and humbly to implore His protection and favor. . . . Now, therefore, I do appoint Thursday, the 26th day of November 1789 . . . that we may all unite to render unto Him our sincere and humble thanks for His kind care and protection. So much for any hint of the desire for a “separation of church and state” to be found in the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment in the Bill of Rights! While our Founders wanted to prohibit the establishment of an official national church, they quite obviously had absolutely no intention of separating God from the American government. Following President Washington’s initial proclamation, days of Thanksgiving were sporadically proclaimed. Another by President Washington in 1795; One by John Adams in 1799; Others by James Madison in 1814 and 1815. But most official Thanksgivings in early America were observed at the state level. By 1815, the various state governments had issued at least 1,400 official calls for prayer and thanksgiving or for prayer and fasting. While our Founders wanted to thank God for the new nation they had just established, Thanksgiving did not become an annual event in America until the time of President Abraham Lincoln. After being importuned by Sarah Josepha Hale, a popular women’s magazine editor, President Lincoln proclaimed the last Thursday in November, 1863, as a day “of Thanksgiving and Praise to our benevolent Father.” He proclaimed this national Day of Thanksgiving in the midst of the darkest days of the Civil War, noting: The year that is drawing towards its close, has been filled with the blessings of fruitful fields and healthful skies. To these bounties, which are so constantly enjoyed that we are prone to forget the source from which they come, others have been added, which are of so extraordinary a nature, that they cannot fail to penetrate and soften even the heart which is habitually insensible to the ever watchful providence of Almighty God. The President continued, No human counsel hath devised nor hath any mortal hand worked out these great things. They are the gracious gifts of the Most High God, who, while dealing with us in anger for our sins, hath nevertheless remembered mercy. It has seemed to me fit and proper that they should be solemnly, reverently, and gratefully acknowledged as with one heart and one voice by the whole American People. The 1863 Day of Thanksgiving was remarkable because it was held during a time in which the Union Army had been losing battle after battle for three extremely brutal and bloody war years. That time was also a pivotal point in Lincoln’s own personal spiritual life. Just several months earlier, the Battle of Gettysburg had resulted in the loss of more than 60,000 American lives—-in a single battle. President Lincoln would later explain to an Illinois clergyman that it was while walking among the thousands of graves at Gettysburg that he first committed his life to Christ. He confessed: When I left Springfield [Illinois, to assume the Presidency], I asked the people to pray for me. I was not a Christian. When I buried my son, the severest trial of my life, I was not a Christian. But when I went to Gettysburg and saw the graves of thousands of our soldiers, I then and there consecrated myself to Christ. That tragedy of 60,000 dead affected Abraham Lincoln’s eternal destiny as well as the rest of his brief remaining earthly life. His dedication to Christ was visible in his public pronouncements for the remainder of his presidency. Since President Lincoln’s 1863 proclamation, each President has issued an annual proclamation declaring a National Day of Thanksgiving to God, although the actual dates varied widely. It was in 1933 that President Franklin D. Roosevelt, another president destined to witness the brutality of war, as well as the chaos of economic collapse, called for an annual national Day of Thanksgiving every fourth Thursday of November. Finally, in 1941, ironically just a few weeks before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Congress permanently established the fourth Thursday of November as an official national Thanksgiving holiday. As we thank God for His blessings this year, we should particularly remember the words of Boston’s Lady Magazine editor, Sarah Josepha Hale, when she urged President Lincoln to proclaim a national Day of Thanksgiving during the midst of the Civil War. She wrote: Let us consecrate the day to benevolence of action, by sending good gifts to the poor, and doing those deeds of charity that will, for one day, make every American home the place of plenty and of rejoicing. Let the people of all the States and Territories sit down together to the “feast of fat things,” and drink, in the sweet draught of joy and gratitude to the Divine giver of all our blessings, the pledge of renewed love to the Union, and to each other; and of peace and good-will to all men. This year, as America faces dark days and severe challenges, Mrs. Hale’s words seem particularly appropriate. Wars, rumors of war, and economic distress have overtaken us yet again. Nevertheless, Almighty God has continued to bless America. It is appropriate that we continue to express our national gratitude and thankfulness to Him for His blessings. Thankfulness, no matter what the external circumstances, has for nearly 500 years expressed the true spirit of America. It is no accident that Thanksgiving is the oldest of all American holidays.