Position paper Diabetes care

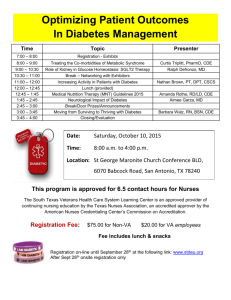

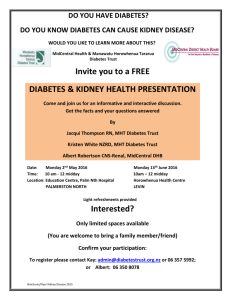

advertisement

The management of chronic care conditions in Europe with special reference to diabetes: the pivotal role of Primary Care Position Paper 2006 1 The management of chronic care conditions in Europe with special reference to diabetes: the pivotal role of Primary Care. 2006 European Forum for Primary Care Editors Luk Van Eygen et al. Printing Sekondant This publication may be reproduced without written prior consent of the publisher, but acknowledgement of the European Forum for Primary Care and the editor is requested. A pdf version is available on the website of the European Forum for Primary Care. This publication can be ordered from European Forum for Primary Care PO Box 8228 3503 RE Utrecht The Netherlands. Tel + 31 30 789 24 80 info@euprimarycare.org www.euprimarycare.org 2 Preface The European Forum for Primary Care was established in 2005, with the purpose of strengthening Primary Care in Europe. Primary Care is care that is community based, permanently available and easily accessible. Among the many activities of the Forum is the formulation of a series of Position Papers from 2006 onwards. Aim of the Position Papers is to provide policymakers in WHO, EU and in the individual European states with evidence and arguments which allow them to support and develop Primary Care. In addition, the Position Papers aim to facilitate the exchange of experience and know how between practitioners in different countries and to identify issues for further research. The Position Papers are the result of consultation and discussion among many relevant stakeholders in Europe, under leadership of one of the members of the Forum. The format and the process of development of the Position Papers gradually will be standardised, resulting in a series, demonstrating the added value of Primary Care. Position Papers 2006 Mental Health in Europe, the role and contribution of Primary Care. Encouraging the people of Europe to practice self care: the Primary Care perspective. The management of chronic care conditions in Europe with special reference to diabetes: the pivotal role of Primary Care. 2007 Prevention and treatment of chronic heart failure in Primary Care Prevention and treatment of COPD/asthma in Primary Care Prevention treatment of chronic renal failure in Primary Care Prevention and treatment of depression, the role of Primary Care 3 The management of chronic care conditions in Europe with special reference to diabetes: the pivotal role of Primary Care. Introduction This position paper focuses on the pivotal role of primary care in chronic care conditions and targets policymakers in the EU and its member states. We argue the need for a concerted approach to define how chronic care programs should be designed, implemented and evaluated to ensure the highest level of quality in chronic care delivery across the different European healthcare systems. The case of diabetes mellitus (type 2) is used as an example. 1 A diabetes epidemic The impact of diabetes on health in Europe can hardly be underestimated. In 2003 the International Diabetes Federation estimated that about 48 million people in Europe suffer from diabetes. This corresponds to a prevalence of 7.8%, which is expected to rise to 9.1% by 2025. By 2025 the direct cost of diabetes is expected to represent between 7% and 13% of the total health expenditure1 . Diabetes has a dramatic impact on mortality, morbidity and quality of life. Diabetes patients have 3- 4 times as much risk to die from cardiovascular diseases. Diabetes is still the commonest cause of blindness at working age, one of the commonest causes of kidney failure and the most common cause of leg amputation2. Although the quality of diabetes care in many healthcare systems is gradually improving, this holds for a part of the patient population only3,4,5,6. Evidence suggests there is still a wide variation in quality of care, with rates of recommended care processes to be unacceptably low7,8,9. 2 Quality of care Although measuring and improving quality is a strong focus in diabetes care, it is still a concept that has left to numerous interpretations. How high quality care for diabetes is defined, often depends on the perspective of the initiator of the program or the concept used to classify the program such as disease or case management. Different stakeholders have different perspectives about quality of care10 and the large number of definitions used, either generic11,12, or disaggregated13,14,15,16 demonstrate the complexity and multidimensionality of the concept17. 4 A good framework for what is considered high quality chronic care is provided by the Chronic Care Model18. The author of the Chronic Care Model states that improvements in six interrelated components (community resources, self-management support, delivery system redesign, decision support, clinical information systems and organizational support) can produce system reforms that enhance patient-provider interactions19,20,21. We strongly subscribe to the Chronic Care Model and the pivotal role primary care has to play in operationalizing its constituents. 3 A diabetes care model rooted in primary care Several models of diabetes care are possible: a primary care-based model, a secondary care-based model or a model of specialised diabetes centres besides routine primary and secondary care. The epidemiological impact and the focus on patient empowerment and efficiency plead for a diabetes care model rooted in primary care, with a pivotal role for the general practitioner/family physician. Diabetes is a complex disease which affects many aspects of patient’s life and requires a long-term follow-up. Diabetes patients often suffer from several chronic problems at the same time. Primary care operating as an interdisciplinary team is particularly well placed to offer this care. The knowledge of the patient’s psychosocial context, previous health experiences and co-morbidities ensure holistic, comprehensive and continuing care22. Specialised care – be it at secondary level or in specific diabetes centres not integrated in primary care – risks to lead to a fragmentation of care. Clinical effectiveness and cost-utility are other important reasons to choose for a primary care-based model. International evidence indicates that health systems based on well structured and organised primary care with adequately trained general practitioners, provide both more cost-effective and more clinically effective care than those with a low primary care orientation23. The evidence for diabetes care points in the same direction24: well structured diabetes primary care – as compared to secondary care - offers at least as good quality care at a lower cost for the patient (though the effect on the overall health cost is less clear). The rising diabetes prevalence represents a big challenge for the European health systems. Ensuring the accessibility of care for all diabetes patients will be most easily achieved in primary care. In 2006 most diabetes patients in Europe are already treated in primary care, without capacity problems. A diabetes care focussed on secondary level is likely to create soon long waiting lists. The saturation of the secondary level has already caused in several countries a shift of patients from secondary to primary care25, but quality of care can only be 5 guaranteed when this shift is accompanied with a proper support and adequate ressourcing of primary care. 4 Crucial elements for diabetes care reform Presently most European countries are in a process of reforming the management of chronic diseases, and more specifically of diabetes. Health systems that were originally designed to deal with acute diseases have to be transformed into systems capable to offer integrated care. The general principles of present thinking on diabetes care management can be summarized as follows: Patients should be active and empowered partners in diabetes care Diabetes care should be provided by an interdisciplinary team Quality monitoring is a prerequisite for efficient diabetes management Information and communication technology are crucial to facilitate integrated diabetes care Prevention and early detection of diabetes require more attention Patients should be active and empowered partners in diabetes care The patient should have a pivotal role in his/her diabetes management. In chronic diseases like diabetes, patients themselves have a strong impact on the progress of the disease. Structured health education should be part of routine diabetes primary care. Evidence reveals a positive effect of both individual and group-based health education on diabetes outcome2627, 28. Individual and group-based health education are complementary strategies which should be both promoted. Till now many diabetes patients in Europe aren’t offered any structured health education at all. Many training programmes exist here and there, but they are often not well validated and cover only a part of the diabetes patients. In general there is a lack of qualified personnel to organise health education29. Diabetes care should be provided by an interdisciplinary team Taking care of a diabetes patient involves a wide range of skills: providing health education and dietary advice, treating hyperglycaemia and other cardiovascular risk factors, examining and treating eye and foot problems, organising the prevention of long-term complications, 6 etc. It is clear this can only be achieved when several disciplines are involved. General practitioners, nurses, health educators, dieticians, podotherapists, ophthalmologists and diabetologists should be involved in this team work. An interdisciplinary team can be a group of health professionals working in the same organisation but more often it is a network of professionals working together and sharing the care protocol. We specifically plead for an enhanced role of the nurse. While titles, qualifications and functions of nurses differ from one country to another, we can roughly discern two profiles26: Nurses with a limited postgraduate training in diabetes care, usually working in general practice. Diabetes care is only one part of their activities. They support the physicians by taking over part of their tasks e.g. in health education and clinical follow-up. Nurses with a more extensive postgraduate training (“diabetes specialist nurses”). They usually work in secondary care, but get more and more involved in primary care as well. Their functions vary greatly, from only health education to clinical follow-up, case management, training of health staff, liaising between primary and secondary, etc. In primary care they usually work at a local level as an external support and resource-center for the primary care team. An enhanced role of the nurse is supported by evidence. Interventions in which, among others, nurses take over some tasks of physicians, resulted in better glycaemic control26,30,31. There are two main reasons to involve nurses in diabetes primary care: quality improvement and the need for subsidiarity. Quality improvement will only be achieved when the nurse can add something to the existing care package i.e. when the introduction of the nurse results in more time spent on follow-up, education, case finding etc. Mere substitution of general practitioners by nurses might lead to equal results under study circumstances, but the question remains if this will be the case in daily practice. The general practitioner should continue to play a pivotal role. In line with the skills, the general practitioner is the person to integrate all input from the team members and information about co-morbidity and psychosocial context into one global approval. The general practitioner ensures the comprehensiveness of diabetes care. See also box 1. An interdisciplinary approach of diabetes primary care is a real challenge, as primary care health workers often work in relative isolation. Shared care protocols have been developed and define the roles and the ways of communication, but their implementation is often problematic. Strategies should be developed to facilitate the implementation. Supportive or repressive measures at national level can be helpful. A more active involvement of local 7 structures that involve both primary and secondary care, is an option to consider. At a local level health workers meet, build personal relationships and have the opportunity to develop shared care protocols in a bottom-up approach. When properly financed, local structures can play an important role in supporting and co-ordinating this process. Another barrier to interdisciplinary diabetes care is the poor coverage of health education, dietetic and podologic advice by health insurances. Not all type 2 diabetes patients need equal contributions from these services, but a consensus should be developed to tailor the package of services to each type of patient. Finally, legislation should ensure an adequate legal basis for the function-profile of each team member. More specifically nurses are often restricted by law to take up certain responsibilities in diabetes care. Quality monitoring is a prerequisite for efficient diabetes management The positive impact of quality monitoring on quality of care has been clearly demonstrated32,33,34. Quality data can be used for feed-back to the individual health worker, financial incentives and/or guidance in health management. While we emphasize the importance of quality monitoring, it should be noted that this is only one aspect of quality management. Training of health staff, peer review, internal audits, promoting use of diabetes registers or call/recall systems, etc. are other important tools to improve quality of care. The notion of quality monitoring in diabetes care is trickling down into national policies. Many countries are at this moment considering or establishing quality monitoring systems. Until now we are not able to make a meaningful international comparison of quality of care. From the experiences so far, several topics for discussion arise. What should be measured? Most quality monitoring systems use a combination of process and outcome indicators. Outcome indicators approximate best the final goal of health care, i.e., in the case of chronic diseases, the longest possible survival at the best possible quality of life. Process indicators are often easier to measure, but can only be used when evidence shows their impact on health status. Sets of indicators will differ from one country to another, but an initiative to ensure some international comparability of data is needed. Important aspects of quality of care are hardly addressed by present quality monitoring systems, e.g. quality of life, equity in health care, management of co-morbidities. For each indicator a target value is set, usually at national level. Ideally target values should take into account the characteristics of the practice population, e.g. demography, comorbidity, socio-economic status and presence of ethnic minorities. 8 Data collection, validation, processing and feed-back require an important investment in terms of finances, technology and human resources. Data should be collected at the level where care is delivered, i.e. for most diabetes patients in primary care. The information and communication system should enable electronic data extraction from medical files, while safeguarding the privacy of the patient. The quality monitoring system should result in a meaningful feedback to the individual health worker or institution. Data processing, validation and feed-back are usually the responsibility of the (public or private) health insurer. Quality monitoring can be linked to financial incentives. Financial incentives can be a powerful tool to improve quality of care, but have also clear disadvantages. Quality of care does not only depend on the health worker’s performance but also on patients’ characteristics, e.g. progress of the disease, co-morbidity, compliance, health beliefs. This is especially the case when quality monitoring is confined to process and outcome indicators only, and does not include indicators relating to the structure in which care is delivered (e.g. on training of staff, use of diabetes registers and call/recall systems, accessibility of services). Quality-based payments can induce risk selection, i.e. removal of “badly scoring” patients from the monitoring system, e.g. by restricting access to primary care or referral to secondary care. They might create a too strong focus on achieving targets, at the expense of the holistic, contextual and integrated approach of the patient. To avoid these risks, quality-based financial incentives should always be combined with other ways to motivate health staff. The experience in the UK shows that quality monitoring is worth the effort (see box 2). The Quality and Outcomes Framework resulted in a very valuable database of chronic patients and in an improved quality of care. The latter was possible in the first place thanks to the huge investments made in the context of the Quality and Outcomes Framework. To what extent the system of target payments contributed to this result is not yet clear. In many countries diabetes is one of the first fields in health care where quality monitoring has been introduced, but it should not be confined to diabetes care or chronic diseases only. Quality monitoring systems should cover all aspects of primary and secondary care. Information and communication technology are crucial to facilitate integrated diabetes care Information and communication technology is crucial to facilitate integrated diabetes care. ICT facilitates quality monitoring by computerised data extraction. ICT can also be used for creating a common medical record and enhancing communication between the members of the interdisciplinary team. Each effort to improve diabetes care should go hand in hand with 9 initiatives to strengthen the information and communication systems. These initiatives should start from national level to ensure system compatibility and innovation. The use of electronic medical records in primary care is not yet universal. Electronic medical records are mainly used for data storage and much less for quality assurance, quality monitoring and communication between health workers. Patients’ organisations should be involved in the organisation of health education, but also in all levels of the policy making process. In some countries patients’ organisations are represented in regional or national diabetes committees. Prevention and early detection of diabetes require more attention Prevention and early detection of diabetes requires more attention. Many countries have taken initiatives in these fields, but programmes often lack financial resources and standardised programmes of assured quality. Lifestyle changes aimed at weight control and increased physical activity are the central objectives in the prevention of type 2 diabetes. The benefits of reducing body weight and increasing physical activity are not confined to type 2 diabetes; they also play a role in reducing heart disease, high blood pressure, etc. There are two main strategies for prevention of diabetes: a population strategy aimed at reducing risk factors in the general population and a high-risk strategy focussed on persons with increased risk of diabetes. The population strategy often targets specific groups, e.g. school children, employers, etc., for which interventions are designed, not always confined to type 2 diabetes only. They are usually initiated by local or national health authorities. The population strategy has on the long term a high potential to reduce prevalence of not diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. It should certainly be promoted, but the role of primary care in this is likely to be limited. National health authorities should take the lead. Patient organisations and other nongovernmental organisations, food industry, schools, etc. should also be involved (see box 3). A high-risk strategy identifies – in a first step – persons with increased risk for diabetes. These persons are subsequently offered health education, lifestyle counselling, follow-up examinations etc. Evidence shows that such interventions in persons with impaired glucose tolerance can reduce the risk to develop diabetes after three years by about 50-60%35,36. However, many questions remain about cost-effectiveness, identification of high-risk groups, operationalisation etc. Finland, as one of the first countries worldwide, has set up a prevention programme for high-risk groups, which will be evaluated in terms of feasibility and cost-effectiveness by 2007 (see box 3). 10 It is generally believed that about one third to half of all patients with diabetes are undiagnosed. While screening for diabetes seems logical in terms of minimizing complications, there is no evidence so far whether this is beneficial to the individual. Studies on the effect of screening are in progress. Opportunistic screening of high-risk persons is an acceptable policy in countries with high diabetes prevalence, but systematic screening programmes cannot be recommended37. 5 A strong primary care In many countries general practitioners are still working in small practices, with little or no supportive staff and no established interdisciplinary network. In such an environment it is unlikely that the general practitioner is able to contribute adequately to the interdisciplinary team, to the monitoring of quality of care, to the organisation of health education or the implementation of prevention and early detection programmes. An overall strengthening of primary care is essential for an efficient diabetes program. Looking at the existing evidence, we should conclude that the triad of global payment systems, patients’ listing and a gatekeeper role for the general practitioner is the basis for strong primary care. Global payment systems are especially important in chronic disease management where many activities e.g. co-ordination can be difficultly remunerated through a fee-for-service system. Patients’ listing enables the primary care team to develop, together with the patient, a long-term health plan, which is the basis of any chronic disease management. The gatekeeper role gives the general practitioner the possibility to give guidance to his patient in his flow through the health system and to ensure co-ordination between health workers. It is promising to notice that in several countries where primary care was traditionally not based on global payment, patient’s listing and gatekeeper system, elements of this triad were recently introduced: the disease management programme in Germany encompasses (limited) global payments for diabetes care; in 2005 France took measures to promote the gatekeeper role of the general practitioner; Belgium introduced a few years ago a voluntary patients’ listing. 6 Conclusions The developments in the organisation of diabetes care illustrate the transition process European health systems are going through. They were designed in the middle of the 20th century to deal mainly with acute diseases, but due to the progress of medicine and the 11 ageing of the European population, the focus has shifted towards chronic disease management. Diabetes care is one of the fields where the implementation of these changes has reached the furthest so far. Important choices have to be made, which don’t affect diabetes care only, but also the overall health care organisation. In this paper we strongly plead for a diabetes care model rooted in primary care. Primary care offers holistic, comprehensive and continuing care to the diabetes patient. Evidence has clearly shown that well structured primary care can provide high quality diabetes care. It is clear that at present many primary care systems in Europe aren’t prepared to take up this task. We widely discussed what reforms are needed. Global payment systems, patients’ listing and a gatekeeper role for the general practitioner are crucial preconditions for effective chronic disease management in primary care. Important investments are required in terms of finances, human resources and technology in order to contribute to more equity and quality. These reforms will not only have their impact on diabetes care, but will strengthen primary care in general and make the future implementation of other chronic disease management programmes in primary care easier. Therefore, the debate on the diabetes care organisation reflects the fundamental choices the European health care systems have to make at the beginning of the 21st century. Box 1. Substitution versus complementarity. Practice assistants in the Netherlands31,38. Between 2000 and 2003 the Netherlands introduced practice assistants in general practice. By the end of 2003 more than 40% of all general practitioners had access to some practice assistant’s capacity. Practice assistants are practice secretaries with 2 years extra training or nurses with one year extra training. They are particularly involved in the follow-up of chronic patients. The degree of task delegation in diabetes care varies from one practice to another. Their tasks encompass routine follow-up, but also protocol-based decisions on treatment change. 33% of the practice assistants prescribe drugs without any supervision. In about half of all practices with practice assistants the general practitioner is no longer involved in routine diabetes care. Several Dutch studies with varying degrees of task delegation have shown that practice assistants provide at least as good care as general practitioners. In one RCT Houweling et al. compared diabetes care fully delegated to practice assistants with the standard care provided by general practitioners. The practice assistants were trained during one week on the use of flow charts for the treatment of hyperglycaemia, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia. Practice assistants obtained similar results as general practitioners for 12 outcome indicators but scored better for process indicators. Patients were more satisfied about the care provided by practice assistants compared with the care by general practitioners. The driving force behind the introduction of practice assistants was not so much quality improvement, but rather shortage of general practitioners. Studies have focused on the question to which extent practice assistants can substitute general practitioners without loss of quality. They show that practice assistants can provide good quality care, but many questions remain about task delegation and legal responsibility. While many practice assistants are prescribing drugs, there is not yet any legal basis for this. DiHAG, the authoritative working group on diabetes care of the general practitioner’s association, pleads for the general practitioner to review diabetes care with the patient at least once year, so that he maintains a sufficient level of expertise in the field. Box 2. The Quality and Outcomes Framework in England39,40. The English National Health Service introduced in 2004 a target payment system: the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF). The QOF is comprised of a range of criteria which are grouped into 4 domains, clinical, organisational, patient experience and additional services. The criteria are designed around best practice and have a number of points allocated for achievement. The total number of points achieved by a practice results into a payment amount which takes into account the size of the practice and the number of patients diagnosed with chronic illness. In 2004/5 the clinical domain consisted of 11 areas amongst which diabetes – representing 99 of a total of 1050 points. The QOF includes both process and outcome indicators for diabetes care e.g. the percentage of diabetic patients who have a record of HbA1c in the previous 15 months, or the percentage of patients with diabetes in whom the last blood pressure is 145/85 or less. Organisational indicators included items as practice leaflets and practice staff education. A single national IT system enables automatic data collection from the practice files. In addition to this each practice is visited by an assessor team comprising of a general practitioner, a lay person and a representative of the local health authorities. Participation to the QOF was voluntary, but the achievement standards were set rather low so that most practices participated and got a considerable extra income (for an average practice of the order of 100 000 € per year). Many practices used the anticipated extra financial rewards to invest in staff and resources. 13 For 2004/5 practices achieved by average 91.3% of the maximum score (and 92.3% of the maximum for the area of diabetes care), which was much more than the 74% put forward in the planning stage. These results suggest an important impact of target payments on quality of care, though evidence from a longitudinal study shows that in the years before the introduction of the QOF the quality of diabetes care in general practice had already been improving considerably41. The QOF has also resulted in a detailed and complete database of chronic disease patients, which is of great use for health care managers and researchers. For the first time diabetes prevalence could be accurately determined at 3.2%. While the impact of the QOF was generally well appreciated, discussion is going on about the choice of indicators, the huge cost related to the QOF and the under-investment in secondary care. Some also fear a too big focus on technical care and achieving targets for the fields included in the QOF, with a loss of comprehensiveness of care. The publication of the names of the 20 best scoring doctors in London is clearly significant for this trend. For 2005/6 the QOF was slightly adapted. The clinical domain was extended from 11 to 18 areas, including diseases as dementia, depression and obesity. The financial reward linked to the number of points achieved was raised by about 60%, which will create an even greater shift of funds from secondary to primary care. Box 3. The Programme for the Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes in Finland (2003 – 2010)42. The prevention programme is based on evidence from the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. This was the first study in the world to show that the risk of diabetes can be markedly reduced by lifestyle modification35. The Finnish Diabetes Association coordinates the programme which consists of three concurrent strategies: 1) The population strategy aims to promote the health status of the entire population by means of nutritional interventions and increased physical activity. It envisages a wide range of interventions e.g. increasing numbers of nutritionists in health care, incorporating nutrition education and physical education in the school curriculum and military training, taking into account the possibilities for physical activity for the general public when planning urban areas, media campaigns, involving food industry to broaden the range of low-fat and low-salt foods on offer, the introduction of a healthy food label etc. Non-governmental organisations are also involved. 14 2) The high-risk strategy is targeted at individuals with a high risk of developing type 2 diabetes. The Type 2 Diabetes Risk Assessment Form is a validated screening tool comprising of eight questions. The test is distributed by the internet, in pharmacies and various public campaign events. People who score high on this assessment form are referred to a public-health nurse. The nurse will screen for obesity, hypertension, impaired glucose tolerance, diabetes and hyperlipidaemia. People are offered individual or group counselling and medical treatment where necessary. 3) The objective of the early detection strategy is to prevent complications of diabetes by giving newly diagnosed patients a good start with focus on nutrition, physical activity and weight control, mostly through group counselling. The feasibility and cost-effectiveness of the high-risk and early detection strategy are being assessed in a pilot project in four districts till 2007. 15 References 1 International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes Atlas. Brussels 2006. www.eatlas.idf.org. 2 World Health Organisation. European Health Report 2002. WHO Regional Publications, European Series, No. 97, Copenhagen. 3 Shaughnessy AF, Slawson DC. Blowing the whistle on review articles-What should we know about the treatment of type 2 diabetes? Editorial. Br Med J 2004; 328:280-2. 4 Winocour PH. Effective diabetes care: A need for realistic targets. Br Med J 2002;324:1577-80. 5 Hirsch IB. The burden of diabetes (care). Commentary. Diabetes Care 2003; 26:1613-4. 6 Goyder EC, McNally PG, Drucquer M. et al. Shifting care for diabetes from secondary to primary care, 1990-5.: review of general practices. BMJ 1998; 316:1505-6. 7 McBean AM, Jung K, Virnig BA. Improved care and outcomes among elderly Medicare managed care beneficiaries with diabetes. Ma J Manag Care 2005; 11: 213-222. 8 Jencks SF, Huff, ED, Cuerdon T. Change in the quality of care delivered to Medicare beneficiaries, 19981999 to 2000-2001. JAMA. 2002; 289 (3): 305-312. 9 Saadine JB, Engelgau MM, Beckels GL, Gregg EW, Thompson TJ, Narayan KV. A diabetes report card for the United States: quality of care in the 1990s. Ann Intern Med 2002; 136: 565-574. 10 Ovretveit J. Health service quality: An introduction to quality methods for health services. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1990. 11 Juran JM. Juran on planning for quality. New York: Free press, 1990. 12 Ellis R. & Whittington D. Quality assurance in health care— a handbook. London: Arnold, 1993. 13 Lohr KM. Medicare: a strategy for quality insurance. Washington DC: National Academy Press, 1990. 14 Donabedian A. Explorations in quality assessment and monitoring. Volume I: The definition of quality and approaches to its assessment. Ann Arbor. MI: Health Administration Press, 1980. 15 Peters T. Thriving on chaos: Handbook for a management revolution. New York: Knopf, 1987. 16 Lohr, K. (1992). Medicare: a strategy for quality assurance. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. 17 De Maeseneer JM, van Driel M, Green LA, van Weel C. Translating research into practice 2: the need for research in primary care. The Lancet 2003; 362:1314-1319. 18 Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: What will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Effective Clinical Practice 1998; 1:2-4. 19 Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, Part 2. JAMA 2002; 288: 1909-1914. 20 Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach, K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA 2002; 288: 1775-1779. 21 Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q 1996; 74: 511-544. 22 WONCA Europe. The European definition of general practice / family medicine. WHO Europe, Barcelona, 2002. Accessed at www.globalfamilydoctor.com/publications/Euro_Def.pdf. 23 Starfield B. New paradigms for quality in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2001; 51: 303-9. 24 Griffin S, Kinmonth AL. Systems of routine surveillance for people with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Library 2000/4. 25 Mathieu C, Nobels F, Peeters G et al. Quality and organisation of type 2 diabetes care. Federal knowledge centre for health care, Brussels, 2006. See www.centredexpertise.fgov.be. 16 27 National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Guidance on the use of patient-education models for diabetes. London, 2003. See www.nice.org.uk. 28 Deakin T, McShane CE, Cade JE et al. Group-based training for self-management strategies in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Library 2004/4. 29 Schlögel R. Diabetes mellitus – a challenge for health policy. Federal Ministry of Health and Women, Vienna, 2006. 30 Renders CM, Valk GD, Griffin S et al. Interventions to improve the management of diabetes mellitus in primary care, outpatient and community settings. Cochrane Library 2002/4. 31 Houweling ST. Task delegation in diabetes primary and secondary care [in Dutch]. Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, 2005. 32 Varroud-Vial M, Charpentier G, Vaur L et al. Effects of clinical audit on the quality of care in patients with type 2 diabetes: results of the DIABEST pilot study. Diabetes Metab 2001 27(6): 666-74. 33 Walker D, Harvey K. Outcomes managements of an ambulatory clinic system population: experience with patients with diabetes. J Miss State Med Assoc 2004 45(6): 163-8. 34 Jorgensen LG, Petersen PH, Heickendorff L et al. Glycemic control in diabetes in three Danish counties. Clin Chem Lab Med 2005 43(12): 1366-72. 35 Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. NEJM 2001; 344: 1343-50. 36 Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. NEJM 2002; 346: 393-403. 37 International Diabetes Federation. Global guideline for type 2 diabetes. IDF, Brussels, 2005. www.idf.org. 38 Houweling ST, Kleefste N, van Ballegooie E et al. Shift of tasks in primary diabetes care [in Dutch]. Huisarts en Wetenschap 2006; 49(3): 118-22. 39 NHS Health and Social Care Information Centre. Quality and outcomes framework information. www.ics.nhs.uk/services/qof (accessed 10 November 2006). 40 Kenny C. Diabetes and the quality and outcomes framework. BMJ 2005; 331: 1097-8. 41 Campbell SM, Roland MO, Middleton E et al. Improvements in quality of clinical care in English general practice 1998-2003: longitudinal observational study. BMJ 2005; 331: 1121-3. 42 Finnish Diabetes Association. Programme for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in Finland. Helsinki, 2003. See www.diabetes.fi/english/prevention/programme/print.html. 17