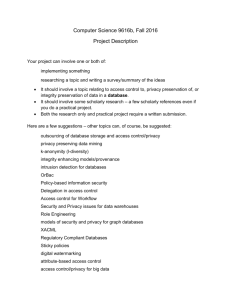

TITLE: Personal Health Record Software by CapMed

Cisco Systems, Inc.

Privacy and Personal Health Records:

Context, Issues and Challenges

Draft – 31 January 2001

Presented by

Jane Sarasohn-Kahn

Management Consultant and Health Economist

The Conundrum of Privacy and Health Care:

Some Thoughts to Consider

“In many respects, the battle for health privacy has already been lost.”

Robert Gellman, National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics

“You have zero privacy anyway. Get over it.”

Scott McNealy, Chairman and CEO, Sun Microsystems

“In the end, privacy is personal, and…depends on you, the individual involved.”

Esther Dyson in her Foreward to The Hundredth Window by Charles

Jennings and Lori Fena, Founders of TRUSTe

79% of Americans agree that the word “privacy” should be added to the

Declaration of Independence.

Louis Harris & Associates survey, 1990

The Context for the Medical Privacy Challenge

“Every day, our private health information is being shared, collected, analyzed and stored with fewer federal safeguards than our video store records.”

Donna Shalala, Secretary of Health and Human Services

That our personal health information doesn’t have the same privacy protection as details about our rental from the latest Blockbuster speaks volumes about the medical privacy debate that has brewed in the United States in the 1990s. In the last decade of the 20 th

century, we experienced a growing openness of medical information systems, transforming stacks of paper locked in cabinets to digital data accessible through an ever-growing list of portals and channels. At the same time, Americans are reaching out and clicking for medical advice in cyberspace, often without understanding the privacy policies of the 13,000 websites dispensing the information.

A data-rich society can offer many benefits: personalization, time-saving, convenience, and customization. As Etzioni points out in the Limits of Privacy , some violations of medical records privacy can serve various common goods, such as medical research, public health, public safety, and quality assurance.

When violations of medical records privacy do occur, ownership of the data is a key issue.

Many providers consider the records in their systems to be their property, while patients argue that their medical information is their own (Annas). A distinction is often made between ownership of the physical record and the right to access or duplicate data that are stored in it.

Policies on health data ownership differ substantially between delivery networks, states and indeed, globally (Schoenberg).

A recent court case highlights the contentious issue of medical record ownership. A federal appeals court reinstated a claim against the Social Security Administration (SSA) brought by a man who alleged he had the right to see his medical records without designating a physician to receive them on his behalf. The Seventh Circuit asserted that the current SSA regulations are

“incompatible” with the clear mandate of the Privacy Act. The patient, who was diagnosed with

AIDS, had been seeking his medical records for three years (Source: AIDS Litigation Reporter,

Bavido v. Apfel, No. 98-4046, 7th Cir., June 13, 2000).

Sensitive Information

Percent of online users who are “always” or “usually” comfortable providing...to Web sites

Very sensitive

Social Security number

Credit card

Phone number

Income

Medical information

1%

3%

11%

17%

18%

Hit or miss

Postal address

Full name

Age

44%

54%

69%

Comfort zone

E-mail address

Favorite snack

Favorite TV show

76%

80%

82%

Source: AT&T Labs-Research, Beyond Concern: Understanding Net Users’ Attitudes About

Online Privacy, Technical Report TR99.4.3

Americans are very sensitive about keeping their health information private. As the table details, the only information more closely-held than medical information is an individual’s Social

Security Number, credit card information, phone number, and income (AT&T Labs).

Privacy of personally identifiable health information matters.

And when personally identifiable health information can be married with personally identifiable information of other sorts (e.g., financial information), the linkage of that data can get very personal, indeed. Many e-health business models depend on identifying and tracking users for a variety of purposes, often without the person’s knowledge or consent (FTC Workshop).

Triangulation of Databases

Retail information

Health information

Financial information

The mining of personal information has already begun, marrying the details of our private lives that are distributed in various networks. Our personal information is scattered around the

Internet, from book purchases and preferences to airline ticket reservations and drug prescriptions. Organizations can use these data and assemble profiles on individuals that lead a path right to your door (or e-mailbox) in the form of marketing or more onerous intrusions into our lives (Garfinkel).

Defining the PHR

In the past several years, there has been a proliferation of products available to health care consumers and providers which fall under the umbrella of “Personal Health Record” (PHR). As an emerging market, there is no definition accepted by the industry, nor is there common terminology used across PHRs. In the current marketplace, these products are referred to in a variety of ways: consumer health records, patient medical records, patient health records, personal medical records, and personal health records. Appendix I presents an inventory of the

PHR vendors currently on the market. All but a few are beyond a beta-stage.

Generally speaking, the PHR can be defined as a repository for storing information that helps describe an individual's health status and is accessible by the patient (and when designated by the patient, a provider or other third party) at a subsequent time.

While many PHRs are web-based and Internet-accessible, there are also PHRs that are loaded from

CD-ROMs for consumer use that do not link with online databases. At the other end of the spectrum, a few companies are trying to create a continuum between the electronic medical record as maintained in a physician office or hospital and the consumer/patient.

Functions vary across PHRs. Some Internet record services focus on basic emergency information; many go further, adding information on diet, exercise and disease-specific content.

Some provide tools for disease management utilizing health diaries, reminders, and online communication of health measurements (e.g., blood pressure, blood sugar levels, etc.).

4HealthyLife.com even has a place to keep your pet's health record.

PHRs vary by several key factors:

Who provides the information in the PHR?

Who maintains the information in the PHR?

Who secures the information in the PHR?

Who has access to the information in the PHR?

What functions does the PHR perform and/or support?

The Internet may be a new place to store medical records, but the idea of having an easily accessible, portable record is not new. For years, military personnel have carried their complete paper medical history with them as they moved from billet to billet. Since 1956, the nonprofit

MedicAlert Foundation has provided bracelets and pendants alerting emergency personnel of patients' medical conditions. MedicAlert serves about 2.3 million members in the United States and has affiliates in 12 countries overseas, and the company is developing their version of a

PHR.

Other non-Internet emergency medical records systems entail simply carrying a card with medical conditions, medications and dosages, allergies, and a copy of an ECG in the wallet or in a pendant around the neck. Communities like Sun City, AZ, have portable medical information forms for seniors that include both clinical data and advance directives.

While most PHRs to-date rely solely on patients to provide content, some request records directly from physicians. The most sophisticated systems get information directly from physicians' electronic medical records.

Thus, there is as yet no standard definition of a PHR. A few analysts are tackling the challenge.

The National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics has identified 3 dimensions of a National

Health Information Infrastructure (NHII): the personal health dimension, the health care provider dimension, and the community health dimension. These three dimensions are not records, per se, but rather virtual information spaces. Each space is defined by what it encompasses, whom it serves, how it is used, and who has primary responsibility for content and control (NCVHS).

The Universe of Health Information

Dimensions of the NHII

Personal Provider

Community

Source: NCVHS, Toward a National Health Information Infrastructure

The Personal Health Dimension (PHD) supports the management of individual wellness and health care decision making. It comprises data about health status and health care in the format of a PHR. PHD information can be supplied by both the individual and/or health care providers.

According to the NCVHS, core elements of the PHD would include:

Patient identification information

Emergency contact information

Lifetime health history

Lab and diagnostic test results

Emergency care information, e.g., allergies, current medications, medical/surgical history summary

Provider identification and contact information

Treatment plans and instructions

Health risk assessment

Health insurance coverage information.

In addition, optional elements include correspondence between patients and providers; instructions about access by other persons and institutions; audit log of individuals/institutions who access electronic records; self-care diaries; personal library of reliable health information resources; and, health care proxies, living wills and durable power of attorney for health care.

The NCVHS emphasizes that there is no single place in the NHII where all content will reside.

The PHR could be stored in one repository: on the consumer’s home computer, on a smart card, on a health plan or provider server, or with a third-party infomediary (e.g., online health portal or

Lifeline).

However, the NCVHS argues that the optimal value of the PHR is allowing information to be

“available for the right person at the right time and the right place.” The consumer ultimately will decide which information will be kept under her control, and which information can be shared with others.

Sittig, et. al., also support the NCVHS approach. They contend,

“Internet-based, personal health care records have to the potential to profoundly influence the delivery of health care in the 21st century by changing the loci and ownership of the record from one that is distributed amongst the various health care providers a patient has seen in his lifetime to one with a single source that is accessible from anywhere in the world and under the shared ownership and control of the patient and his provider(s).”

Based on this vision, Sittig, et. al., developed a comprehensive definition of the PHR. In their paper, the authors categorize PHRs into three segments: personal health records, internet-based medical records, and personal health profiles. These are defined as follows:

“Personal health records (PHRs) are created and maintained by an individual patient, or healthcare consumer, based upon their own understanding of their health conditions, medications, problems, allergies, vaccination history, etc. Useful features of PHRs include the

ability to enter and record important health events, calculate health risk indices, do simple medication interactions, and perhaps print a copy to take to the physician's office or on vacation.

Such a record can help a patient concisely explain their health problems when they meet with their doctor. In addition, it could help document information that may be useful when filing health insurance claims.

“Internet-based medical records are a sub-set of the physician's actual medical record as maintained in an electronic medical record (EMR), which is created on the Internet by the provider in a secure web site and shared by patient and physician alike. Features of the internet-based record include all of those of the PHR plus the ability for the patient to communicate with one's providers, request prescription refills and appointments, view a sub-set of the true medical record, see who has accessed the EMR (audit report), serve various electronic commerce requests such as prescription fulfillment at an Internet pharmacy, perform highly personalized and tailored information retrieval for a patient based on their true diagnoses and medications or interests, do automated claims submission and coordination, etc.

“Personal Health Profiles are a medical knowledge-based characterization of a user of a medical information service. Such a technology facilitates convenient and personalized access to knowledge produced by medical practice--the primary knowledge construction process.

Therefore, a personal health profile enables exchange, debate, and reasoning about personal experiences with disease and the health care system, as a secondary knowledge construction process. A user can also be directed to specific chat rooms and message boards where patients and caregivers debate and exchange information regarding their personal experiences with disease and health care.”

Another typology has been developed by First Consulting Group (FCG) which defines five types of PHRs.

Patient-maintained personal medical record.

The largest numbers of providers of consumer health records are in this category. The focus of these products is to track medication consumption and health events.

EMR extension.

This is an extension of the physician’s electronic medical record onto the

Internet, where the consumer/patient can look at the record and check on its content. The record is maintained by the physician and by the medical organization, and is available to the patient in an online format. The major physician medical record vendors are all developing their version of the EMR extension. MedicaLogic has led this pack with its Logician and

AboutMyHealth/98point6 product.

Provider-sponsored data management.

This service is offered by health providers. There are several home-grown examples of this type of PHR, including the PCASSO project at the

University of Southern California and a project at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center in

New York.

Personal Web site.

This is a variation on the patient-maintained personal medical record .

It is sponsored by the physician and creates a communication vehicle between physician and

patient that can include things like reminders for immunizations or flu shots or allow for appointment scheduling or prescription refills. Very often, personal Web site products offer monitoring tools for programs like disease management programs, in which regular collection of data from the patient is desired.

Patient interface.

This PHR variant is problem- or disease-focused and sometimes also involves interactive voice-response technology as well. Like the personal Web site, this product/service allows for regular communication between physician and patient and the regular collection and exchange of data and information.

The PHR is clearly in a state of market emergence. The next few years will see substantial market consolidation as those consumers (and some physician, plan and provider sponsors) who adopt the PHR will be voting with their feet and pocketbooks. As consolidation and market adoption occurs, it will become clearer what consumers (and, particularly, segments of consumers) demand.

One key obstacle to PHR adoption is the thorny issue of medical privacy. This will be addressed in the next section.

Privacy and Personal Health Information:

Invasion of the Record-Snatchers

Most of us recognize that our privacy is at risk. According to a 1996 nationwide poll conducted by Louis Harris & Associates, 24 percent of Americans have “personally experienced a privacy invasion.”

But what is privacy, particularly as it relates to personal health information? The National

Research Council’s report,

For the Record: Protecting Electronic Health Information, provides this definition: An individual’s right to limit the disclosure of personal information (National

Research Council).

In August, 2000, Consumer Reports published an article titled, “Who Knows Your Medical

Secrets?” The publication, targeted to a general audience, included a story about a teenage girl who made prank calls informing people who had visited a hospital emergency room that they were pregnant or had AIDS. Those called took the news seriously; one victim attempted suicide.

The girl had retrieved their names and phone numbers from the hospital computer while visiting her mother, who worked at the hospital.

Just by knowing the birth date and ZIP code of the governor of Massachusetts, Latanya

Sweeney, a computer-privacy researcher at Carnegie Mellon University, was able to retrieve his health records from a supposedly anonymous database of state employee health-insurance claims. Sweeney also demonstrated that she could do the same for 69 percent of the 54,805 people on the voting list of Cambridge, MA.

How large is the problem of medical privacy? It’s so large that the draft privacy regulations first proposed by the Department of Health and Human Services as part of the Health Insurance

Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) generated over 50,000 comments for review. The

General Accounting Office analyzed the comments and discovered the inherent competition between patient privacy and the legitimate – and sometimes less-than-legitimate -- needs for information.

A few illustrations of the contentious uses of personal health information illustrate some

Americans’ concerns.

E-Detailing the Consumer. For many years, direct mail companies have been amassing detailed household-level information on consumers. Some of it comes from public sources such

as census, mortgage, and motor vehicle records. A substantial amount comes from voluntary disclosures that are not obvious to the consumer. Each time a rebate form is returned to a manufacturer; each catalog purchase; each warranty registration adds to the databasing of personal information.

There is a huge amount of health information amassed in commercial databases, as well. One of the world’s largest direct mail and credit companies, Experian, offers the Behavior Bank and Z-

24 products. Clients can buy mailing lists of, for example, 990,070 Americans with bladder control problems, or 2,492,820 with high cholesterol.

Currently, there are no laws governing the use of information in these commercial databases.

Benevolent employers? Many employers have had legal access to employees’ medical records.

A University of Illinois Study of 84 Fortune 500 companies found that 35 percent inspected medical records before making job-related decisions (Los Angeles Times). A national survey of employers by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 30 percent had access to the records

(Consumer Reports). Another study found 200 instances where employers and insurance companies had used information from genetic tests to discriminate against applicants (Geller, et. al.).

“In the employment setting, discrimination among individuals has long been legally, ethically, and socially acceptable” (quoted in Rothenberg, et. al.). On the federal level, the ADA and

HIPAA appear to offer limited protection from discrimination but do not prohibit employers and insurers from gaining access to genetic information. There is currently no uniform protection against the use of, misuse of, and access to genetic information in the workplace.

A recent report from the Employee Benefit Research Institute (EBRI) found that Americans are worried about the privacy of their personal health information – especially with the growth of electronic transfer of medical records. These data demonstrate the struggle between protecting personal medical privacy while sharing necessary information for safe medical care, medical research, and efficient business practices.

Violating your own rules. The California HealthCare Foundation recently examined the privacy practices of 21 of the most popular health-care sites and found, in some cases, that they were violating their own written privacy guidelines -- usually by sending personal information to third parties without the knowledge or consent of site visitors.

Mining for gold. Data mining is a recent business practice that allows companies to access and recombine previously scattered data. The unanswered question is how far Internet health companies will go in exploiting this rapidly growing trove of information on consumer-health conditions and behavior. So far the position of most Internet enterprises seems to be that no amount of personal profiling is too much as long as the technology avoids knowing your name.

Hands in the cookie jar. Much of the privacy issue centers on the use of cookies to track viewer information. Cookies may be session cookies or persistent cookies. While a session cookie disappears after the consumer leaves a website, a persistent cookie is a permanent file and

must be deleted manually. On the positive side, there are time-saving benefits for a consumer using a persistent cookie, such as storing a user’s name and password, or personalizing a site with credit card information for future purchases. However, persistent cookies also permit collection of information about how individuals use the site -- which pages they access, the purchases they make, and their credit card information. If such information is aggregated, how the information is used becomes a concern.

When this information includes personal health information, it could provide a profile of that person's medical condition. Such a profile could be created by the patterns of use of health and medical sites, online purchases of over-the-counter or prescription medications, or even of personal information shared via online surveys, chat rooms, or discussion groups.

Privacy horror stories make for good press. According to a TIME/CNN poll, most Americans

(87% of respondents) believe patients should be asked for permission every time any information about them is used. This is not an irrational reaction. In the past decade, there have been numerous publicized violations of confidential medical information disclosures:

In Indianapolis, the medical records of patients of a psychiatrist, who treated sexual problems, were inexplicably posted on a website accessible to the public.

The Harvard Community Health Plan until recently had maintained medical records containing details psychotherapy notes accessible to all clinical employees of the plan.

At the University of Michigan Health System, patient records could be accessed by anyone through a publicly available search engine until this security breach was discovered.

(Goldman)

There was the assumed violation of medical confidentiality that forced tennis star Arthur

Ashe to go public with his AIDS status once it had been published by USA Today.

The story of a banker on a state health commission who accessed a list of local cancer patients and then cross-referenced it to a list of bank customers who had outstanding loans -- using the medical information to call in the loans of the cancer patients.

The University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle confirmed that a hacker downloaded files in the summer of 2000 from computer systems containing medical data on more than

5,000 patients.

One result of this public concern is that patients often exhibit behavior that shields them from intrusive uses of their health information, such as doctor-switching, paying cash, or withholding information from their physicians about medical history. This lack of reliable information may compromise diagnosis, treatment and favorable outcomes; and, ultimately, increase costs to the health care system.

Consumers’ privacy concerns are a major obstacle toward the mass adoption of the PHR. The next section will discuss the drivers promoting PHR adoption, along with the slowing influences.

Consumer Demand for the PHR: Drivers and Obstacles

The number of Americans accessing the Internet for health information nearly doubled in one year from 1999 to 2000 (CyberDialogue). Clearly, consumers view the Internet as a useful tool for, at a minimum, accessing health information.

e-Health Population is Growing as Quickly

80

70

as the General Online Population

Millions of U.S. adults

All adults online

75.8

60

50

40

30

20

31.3

53.5

17.3

65.4

e-Health consumers

40.9

23.6

10

0

13.4

1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 Q12000

Source: CyberDialogue, 2000

Consumer adoption of the Internet as a health resource is driven by a larger phenomenon of consumer empowerment. The New Consumer, as defined by Institute for the Future, is one who has at least a year of college education, annual family income over $50,000, and owns a PC. By

2005, this population will make up over 50 percent of the U.S.

This population is looking for:

Choice

Control

Service

Branded experiences

Information.

As baby boomers and Generation X’ers age, two phenomena are converging: interest in health information and medical management, and adoption of digital technologies. Together, these drivers influence the consumer toward the adoption of the PHR.

Another important factor influencing the adoption of the PHR is the transition from defined benefit to defined contribution. Employer-sponsored health plans are experiencing painful cost increases, greater than three times the rate of general inflation in 1999 and more than that forecasted in 2001. The move toward defined contribution speaks to the consumer’s desire for more control and choice, and it gets employers out of the health care business to some extent.

Under a defined contribution program, employees make health care financial allocation decisions themselves across a wide range of plans available in their local marketplace. As more companies move their employees toward defined contribution programs, consumers will need tools for managing their health information and resources. The PHR can be tailored to fill this need.

Consumers and e-Health: the Value Proposition

Value

Health

Transactions

Tele-care

Telemedicine

Disease management

Home-based telemetry

Consumer/Provider

Communication

Info Access

Medline

Disease Specific

Product Centric

Personalization

Personalized news

Risk profiling

Online record

Appointment scheduling

Support communities

Quality comparison/report cards

Internet Time

E-Prescription

Drug Authorizations

Eligibility/Referral

Marry the convergence of health care empowerment with technology adoption, add a dose of

New Consumer attributes along with migration toward defined benefits in the workplace, and the adoption of the PHR appears to have a promising future. The more control the health care consumer wants to take on herself, the higher the value of e-Health will be.

But the value proposition calculus must also account for the liabilities – perceived or real – of

PHRs. The issue of privacy is the major obstacle toward mass consumer adoption of PHRs.

While 78% of e-health consumers are receptive to exploring ways to manage health using the

Internet, 43% of them still see the Internet as a “serious threat to my personal privacy.” Among

U.S. adults as a whole, 49% see the Internet as a serious threat to their privacy. (Gallup)

The Gallup Organization has undertaken a number of surveys in the realm of medical privacy.

In the national sample of 1,000 adults taken in September 2000, almost 90% of those surveyed said that the privacy of their personal health information is important, and almost 85% said they are concerned that this information could be given to others without their consent. Although almost all survey participants trust their doctors to keep their medical information private and secure, only two-thirds trusted hospitals, and less than half trusted insurance and managed care companies. A predominant 88% said they would not trust a Web site to protect this information.

Consumers Feel it is Very Important to Keep Medical Records Confidential

Educational

History

Employment

History

Not at all

Not too

Somewhat

Medical

Records

Very

Financial

Information

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

Source: Gallup, Public Attitudes Toward Medical Privacy, 26 September 2000

Most Americans are unwilling to store or transmit personal health information over the Internet, according to Gallup.

In the national Gallup survey, 77 percent of all respondents said the privacy of their personal health information is very important, and 84 percent of all respondents said they are very concerned or somewhat concerned that personal health information might be made available to others without their consent.

As a result of privacy concerns, only 7 percent of respondents said they are very willing to store or transmit personal health information on the Internet, and only 8 percent felt a Web site could be trusted with such information. In contrast, 90 percent said they would trust their doctor to keep their personal health information private and secure, and 66 percent said they would trust a hospital to do the same. Forty-two percent said they would trust an insurance company and 35 percent would trust a managed care company. Clearly, consumers’ consider their relationship with their personal physicians to be the trustworthiest compared with their interactions with other stakeholders in health care.

When asked who should be able to access and place information into medical records, physicians were overwhelmingly indicated, followed by hospitals. Among all U.S. adults, 87% said doctors should have access to medical records and 90% said they should, with permission, be able to place information into medical records. Among online adults, 87% said doctors should have access to medical records and 91% said doctors should be able to place information into medical records. Among e-health consumers, 89% said doctors should have access to medical records and 93% said physicians should be able to place information into medical records.

Permission Marketing Culture - Consumers

Want to Give Permission Before Releasing

Medical Records

5%

95%

Percent of consumers who believe that permission should be obtained before releasing medical records.

Source: Gallup, Public Attitudes Toward Medical Privacy, 26 September 2000

What’s most clear from the various surveys on medical privacy is that consumers want to control where their health information goes. Hence, a permission marketing culture must diffuse throughout the health care industry. This will be a significant cultural change for providers, plans, pharmaceutical companies, and the entire industry.

The HIPAA-Cratic Oath and the PHR

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act 1996 (PL 104-191) was signed into

Federal law in 1996, spurred by the bipartisan legislative team of Senator Nancy Kassebaum (R-

KS) and Senator Edward Kennedy (D-MA). HIPAA has three overall objectives:

To ensure insurance portability for workers

To combat fraud and abuse

To achieve administrative simplification.

The value proposition of HIPAA is that enhanced privacy of medical records will ensure better quality of healthcare and, in turn, medical data integrity. According to DHHS, the underlying approach is to accelerate the move from paper-based administrative and financial transactions to electronic transactions through the establishment of national standards. The standards addressed in HIPAA include:

Transactions

Code Sets

Unique Identifiers, for Individuals, Providers, Employers, and Health Plans

Security

Privacy.

Although part of so-called “administration simplification,” the implementation of the privacy regulations, issued by President Clinton on December 28, 2000, will be far from simple.

HIPAA’s privacy regulations establish a basic privacy framework but set no technical requirements. Furthermore, if a State has a higher level of privacy protection for personal health information, the State can apply to DHHS for an exemption from the Federal rules. At least 20

States had more restrictive privacy laws as of January 2001.

With respect to medical records in general, HIPAA’s privacy regulations are clear:

The regulations cover plans, providers and clearinghouses.

Providers are required to obtain patient consent to use information for health care service payment, treatment, or health plan operations.

Patients must be given details on how their personal health information will be used.

Patients must give consent (“opt-in”) for information to be disclosed for uses other than payment, treatment or health plan operations.

Physicians have discretion to send as much information as they deem necessary when referring patients to other providers for medical treatment

HIPAA is no panacea for solving the medical privacy challenge. The fact is that every state already has laws and regulations governing health information, as well as common-law privacy rights that protect private information about individuals. These rights can include but are not limited to personal health information. Furthermore, a variety of other laws address some aspect of privacy. The result is a patchwork quilt that doesn’t comprehensively cover medical privacy.

Privacy is a Patchwork Quilt

50 State laws

Electronic Communications Privacy

Act of 1986

European Privacy Directive

Fair Credit Reporting Act of 1970

HIPAA

FTC

Gramm-Leach-Bliley

Right to Financial

Privacy Act of 1978

Privacy Act of 1974

Recent legislation:

Anti-spam bill (Unsolicited Commercial Electronic Mail Act of 2000)

The Privacy Policy Enforcement in Bankruptcy Act of 2000

Delahunt and Bachus’s bill (July 2000)

Furthermore, some laws may actually conflict. Christopher Gallagher, Esq., a privacy legal expert, has researched the potential conflicts between HIPAA and the Gramm-Leach-Bliley

Financial Modernization Act of 1999 (GLBA). GLBA was intended to repeal the Glass Steagall

Act of 1933. Glass-Steagall separated banks, brokers and insurers to protect consumers from an unstable economy. In addition to deregulating financial services markets, GLBA also offers personal financial information privacy protections.

As the FTC has noted in the preamble to the final rule of Privacy of Consumer Financial

Information,

“Given the broad definition of ‘financial institution’ under GLB Act, certain entities, such as health insurers, are subject to these privacy rules as well as rules promulgated under HIPAA regarding the appropriate handling of protected health information. Accordingly, financial institutions may be covered both by this privacy rule and by the regulations promulgated by HHS under the authority of sections 262 and 264

of HIPAA once those regulations are finalized. Based on the proposed HIPAA rules, it appears likely that there will be areas of overlap between the HIPAA and financial privacy rules….After HHS publishes its final rules, the Agencies will consult with HHS to avoid the imposition of duplicative or inconsistent requirements” (FTC, Privacy)

What are HIPAA’s impacts on the PHR? In closely analyzing HIPAA’s privacy regulations, it can be concluded that there are privacy implications that could impact the PHR. This statement is equivocal because the question is more appropriately answered with, “It depends.”

PHR Privacy is Compromised as the Locus of Patient Control Dissipates

Level of Privacy

Complication

Consumer- and

Internet Portal

Managed

Provider-

Managed

Consumerand Provider-

Managed

Consumer-

Managed

Patient Provider Portal Locus of

Control

Source: JSK

Generally speaking, whether HIPAA applies to a specific PHR depends on:

Who is the custodian of the PHR?

Who maintains the PHR?

Is the PHR electronically networked or communicating with a provider, plan or clearinghouse?

Has a provider communicated information for a treatment plan into the consumer’s PHR?

If a PHR is self-compiled and maintained by the individual for that individual’s own use, then there would be a presumption that consent or authorization is implied if the individual shares that

PHR with a provider or others. The individual is in control -- but most importantly, the record was not maintained or created by a provider or a plan for purposes initially of treatment or payment. If, however, the PHR is established as part of a plan of treatment or once it becomes part of the plan of treatment, then it would conceivably fall under the HIPAA umbrella.

HIPAA will apply whenever a PHR is created or maintained by a provider, a health plan, or a clearinghouse who transmits any individually identifiable health information electronically using

a HIPAA transaction standard. The individually identifiable health information within the PHR would then be protected by the HIPAA privacy rule. The privacy rule would make the health plan, provider, or clearinghouse liable for mis-use or mis-disclosure of the protected health information, including mis-use or mis-disclosure by any business associate of the plan, provider, or clearinghouse.

If web services allow individuals to establish PHRs, and if the web services are not HIPAAcovered entities (i.e., plans, providers, or clearinghouses), then the PHR-creation and maintenance functions would not be covered under HIPAA. Nonetheless, if providers get involved with these online PHRs at a later stage, HIPAA could arguably cover this scenario.

Furthermore, web-based PHRs may run afoul not of HIPAA but of other Internet privacy regulations and laws under consideration.

An Interim Conclusion Enroute to HIPAA Implementation

This White Paper seeks to answer the basic question, “What are the privacy implications of the

PHR?” The response to the question is complicated by several factors that must be monitored over time:

The maturing and consolidation of the PHR market, as well as a converging definition or typology for the product(s).

The “seasoning” and analysis of HIPAA privacy regulations and future case law.

The change of administration in Washington and its approach to privacy, medical and otherwise..

The 107 th

Congress’s actions on privacy legislation as well as Internet regulation.

What is clear is that consumers are driven to take more control over their lives, demand higher levels of service from health care providers and payors, and more freedom of choice in benefit plans. At the same time, consumers will need to take some responsibility for protecting their personally identifiable health information. As such, privacy is not so much a right but a personal skill (Jennings and Fena). Appendices II through IV offer consumers advice on keeping health information private, based on recommendations from several key medical privacy stakeholders.

The Privacy Seesaw

Protecting individual information vs.

Facilitating modern commerce

As a society, Americans need to reach consensus about how we think about health information and information sharing. Information is both a private resource and a public good (NCVHS).

Developing and implementing new privacy enhancing technologies will be crucial to the solution of promoting ongoing trust, privacy and security and the healthy growth of electronic commerce.

However, not until we appreciate and address the complex relationship between personal health

information and the promotion of commercial interests and a growing economy will any of us, individually, enjoy the ultimate right addressed by Warren and Brandeis in their seminal essay,

The Right to Privacy – the right to be left alone.

A second White Paper is in developing which will cover four future scenarios on privacy and personal health records. This will be available in mid-March 2001.

Appendix I

Personal Health Record Vendors

This list of PHRs is current as of 31 January 2001. The products vary by functionality, target sponsor (e.g., health plan, end-user consumer, health provider, etc.) and locus of storage and maintenance. The list is provided as simply a roster demonstrating the vast number of PHR permutations available on the market. They are listed in alphabetical order.

Vendor/Sponsor

4HealthlyLife

MedicaLogic/MedScape

Accordant

American Medical Association

CapMed

Product

4HealthLife

AboutMyHealth (formerly 98point6

Health Communities

Personal Health History

Personal Health Record

CareSoft

Catholic Healthcare West

Cerner

Cuffs Planning & Models

Telemedical.com

DataCritical

DrKoop

Elixis Corporation

GlobalMedic

Medical Network Inc.

HealthCentral

HealthCPR Technologies

Health Magic

Healtheon/WebMD

HealthRadius i-beacon.com

Imetrikus

Kaiser Health Plan

Lifechart Inc.

Lifeclinic.com

McKessonHBOC

Medifile Inc.

MedicalRecords.com

Partners Health Plan

Protocol Driven Healthcare Inc.

Drugstore.com

National Institutes of Health/NLM

PersonalMD

PersonalPath Systems

PrimeTime Software

RxRemedy

Softwatch

CareSite

Your Health

IQ Health

Health-Minder

Your Health Record

YourHealthChart.com

MyHealth

YourHealthChart eHealth Record

MyHealthAtoZ

LifeView

BankofHealth.com

HealthCompass

MyHealthRecord

Joint ventures with PersonalMD and TRW i-Return Consumer Health Record

MyHealthChannel

Kponline.org

Lifechart.com

PHR/Kiosk joint venture with Kmart

Personal Health Profile

Personal Health survey

(in beta)

WellPatient.com

MyHealthyLife.com*

MyHealthNotes

PCASSO (sponsored by Data General and Oracle)

PersonalMD

PersonalPath.com

MedicalHistory.com

DoHealth

Personal Profile

UrgentLink

WellMed

Your Online Safety Deposit Box

WellRecord

*Including the modules MyAllergy, MyAsthma, MyBackPain, MyBladder, MyBP, MyCardio,

MyCHF, MyDepression, MyDiabetes, and MyJoints.

Source: JSK, as of 31 January 2001

Appendix II

AHIMA’s Advice on Keeping Your Own Health Record

Maintaining a personal health record at home is one of the best ways to assure that you will have access to your health information. Keeping a personal health record can be as simple as maintaining a file folder in which you keep relevant medical data. While it is not necessary to get copies of your record every time you visit your doctor, you should get copies of operative reports, discharge summaries, and significant tests from any hospital visit. You should also incorporate into this file the following categories of information when they apply:

Personal identification

Person(s) to notify in case of an emergency

Name and phone number of your personal physician, dentist, optometrist, and pharmacist

Current medications

Immunizations

Allergies

Important events and dates in your personal and family medical histories

Important test results such as X-rays and EKGs

Eyeglass prescription

Dental information (dentures, bridges, etc.)

Copies of advance directives

Organ donor authorization

Health insurance information

Individuals with special medical conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, or heart conditions should consider wearing an alerting device to inform others of their condition in an emergency.

Source: AHIMA website, accessed on 30 January 2001

Appendix III

The Internet Healthcare Coalition's e-Health Code of Ethics

< www.ihealthcoalition.org/ethics/ehcode.html>

Sites that collect personal data should:

Take "reasonable steps" to prevent unauthorized access to or use of personal data, for example, by encrypting data, protecting files with passwords, or using appropriate security software for all transactions involving users personal medical or financial data;

Make it easy for users to review personal data they have given and to update it or correct it when appropriate;

Adopt reasonable mechanisms to trace how personal data is used, for example by using "audit trails" that show who viewed the data and when;

Tell how the site stores users' personal data and for how long it stores that data;

Assure that when personal data is de-identified (that is when the users' name, e-mail address, or other data that might identify him or her has been removed from the file) it cannot be linked back to the user.

Source: Internet Healthcare Coalition website

Appendix IV

Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC)

Maintaining Medical Record Privacy – Recommendations to Consumers

Protect the privacy of your Social Security Number.

Tell your physician everything necessary for proper treatment, but “think twice before disclosing information that has no bearing on your health.” (Consumer Reports, October

1994, p. 629).

Ask your doctor if any of the records can be accessed from outside the office. If so, ask for what purpose they may be accessed.

Before the office sends your medical records to another party, such as an insurance company, ask to view them for accuracy.

Ask for a notification if the records are ever subpoenaed.

Controlling access to other personal information.

Bibliography

AIDS Litigation Reporter

. “Man wins right to challenge government agency over access to medical records.” September 11, 2000.

Anderson, James G. “Security of the distributed electronic patient record: a case-based approach to identifying policy issues.”

International Journal of Medical Informatics. 60(2000):111-118.

Annas, G. J. “A national Bill of Patients’ Rights.”

New England Journal of Medicine. 338

(1998):695-9.

AT&T Labs. “Beyond concern: understanding net users’ attitudes about online privacy.”

Technical Report TR 99.4.3.

14 April 1999.

California HealthCare Foundation. Medical privacy and confidentiality survey: final topline.

January 10,1999.

California HealthCare Foundation. National survey: confidentiality of medical records .

Oakland: CHCF, January 1999.

Cate, Fred. Privacy in the information age . Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1997.

Center for Democracy and Technology. Privacy and health information systems: a guide for protecting patient confidentiality . Washington, DC: CDT, 1996.

Coleman, David. “Who’s guarding medical privacy?”

Business & Health. March 1999.

Donaldson, Molla S.; Kathleen Lohr, Editors. Institute of Medicine. Health data in the information age . Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1994.

Employee Benefit Research Institute. Privacy and quality in health care . Vol. 21 Number 12.

Washington, DC: EBRI, December 2000.

Etzioni, Amitai. The limits of privacy.

New York: Basic Books, 1999.

Federal Trade Commission. Privacy of consumer financial information . Final Rule. 16 CFR

Part 313. May 24, 2000.

Federal Trade Commission. Privacy online: a report to Congress . June, 1998.

Federal Trade Commission. Workshop on online profiling . Accessed at

<http://www.ftc.gov/bcp/profiling/index.htm> September 18, 2000.

Gallagher, Esq., Christopher C. “The Perfect Storm: The GLBA-HIPAA Convergence.”

Presented 11 October 2000 at the GlasserWorks Seminar on Privacy Law 2000.

Gallup Organization. Public attitudes toward medical privacy . 26 September 2000

Garfinkel, Simson. Database nation: the death of privacy in the 21 st

century . Sebastopol, CA:

O’Reilly, 2000.

Gaunt, Nicholas. “Practical approaches to creating a security culture.”

International Journal of

Medical Informatics 60 (2000) 151-157.

Geller, L.N.; J.S. Alper, P.R. Billings, C.I. Barash, J. Beckwith, M.R. Natowicz. “Individual, family, and societal dimensions of genetic discrimination: a case study analysis.” Science and

Engineering Ethics 2 (1996) 71-88.

Goldman, J.; D. Mulligan. “Privacy and health information systems,” in:

A Guide to Protecting

Patient Confidentiality , Center for Democracy and Technology, Washington, DC, 1996.

Gorman, Christine. “Who’s looking at your files?”

Time Magazine.

May 6, 1996. Pp. 60-62.

Herrera, Stephen. “Hypocritic oaths.”

Red Herring. October 2000, pp. 240-242.

Hodge JG Jr, Gostin LO, Jacobson PD. “Legal issues concerning electronic health information: privacy, quality, and liability.”

JAMA. 1999;282:1466-1471.

Institute for the Future. Catch the First Wave: Twenty-First Century Health Care Consumers ,

1998.

Institute for the Future. Health e-People, Menlo Park, CA. 2000.

Institute for the Future. The Future of the Internet in Health Care , Menlo Park, CA. 1999.

Jennings, Charles; Lori Fena. The Hundredth Window . New York: The Free Press, 2000.

Metzger, Jane; Marian Carter, Erica Drazen . Personal Health Records: Current Market, Future

Trends.

First Consulting Group, Inc. 2000.

Moran, Donald W. “Health information policy: on preparing for the next war.”

Health Affairs

17(1998):9-22.

National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics. Toward a National Health Information

Infrastructure . June 2000.

National Research Council. For the Record: Protecting Electronic Health Information.

Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1997.

Neame, Roderick. “Communications and EHR: authenticating who’s who is vital.”

International Journal of Medical Informatics 60: (2000) 185-190.

O’Harrow, Jr., R. “Firm tracking consumers on web for drug companies.”

Washington Post.

14

August 2000, E1.

Raymond, Joan. “The cyber file cabinet.”

American Demographics.

July 2000.

Rind, David M.; Isaac S. Kohane, Peter Szolovits, Charles Safran, Henry C. Chueh, G. Octo

Barnett. “Maintaining the confidentiality of medical records shared over the Internet and the

World Wide Web.”

Annals of Internal Medicine 15 July 1997. 127:138-141.

Rothenberg, Karen; Barbara Fuller, Mark Rothstein, Troy Duster, Mary Jo Ellis Kahn, Rita

Cunningham, Beth Fine, Kathy Hudson, Mary-Claire King, Patricia Murphy, Gary Swergold,

Francis Collins. “Genetic Information and the Workplace: Legislative Approaches and Policy

Challenges.”

Science.

v. 275(21 March 1997):1755-1757.

Rubin, Alissa J. “Records no longer for doctors’ eyes only.” Los Angeles Times. September 1

1998, p. A-1

Schoenberg, Roy; Charles Safran. “Internet based repository of medical records that retains patient confidentiality.” Bmj.com, Volume 321, 11 November 2000.

Sittig, Dean F.; Blackford Middleton, Brian L. Hazlehurst. “Personalized health care record information on the Web.” Presented at the Quality Healthcare Information on the ‘Net ’99

Conference held October 13 1999 in New York, NY.

Swire, Peter P.; Robert E. Litan. None of your business . Washington, DC: Brookings

Institution, 1998.

U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment , Medical monitoring and ccreening in the workplace: results of a survey-background paper , OTA-BP-BA-67. Washington, DC: USGPO,

October 1991.

Wahlberg, D. “Patient records exposed on Web.” Ann Arbor News , 10 February 1999, 1.

Warren, Samuel; Louis Brandeis. “The right to privacy.”

Harvard Law Review . December 15,

1890, Vol. IV, No. 5.

Westin, Alan F.; Danielle Maurici. E-Commerce & Privacy: What Net Users Want.

Privacy &

American Business and PriceWaterhouse Coopers, June 1998.