TOK Unit 1 - Philosophy Online

advertisement

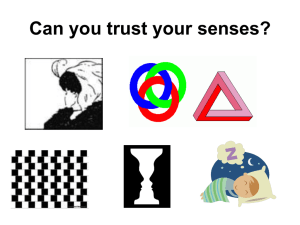

Theory of Knowledge – Unit 1 – Scepticism Introduction We have all had the experience of being unsure or mistaken about something: you mistake someone's voice on the phone for someone else's; you wonder whether you've locked the door after you've left the house; you think it's Tuesday when it is actually Wednesday. These sorts of situation are common and do not tend to cause most people any great deal of anxiety - we simply accept them as normal incidents. But what if we were mistaken all the time? Is this possible? From the very first beginnings of philosophy in ancient Greece, philosophers have been discussing this question. On one side of the discussion are the Sceptics who argue that it is impossible to be certain about anything. They point to similar examples as the ones I have given above, arguing that if we can be deceived about such simple things, who is to say that we are not mistaken more often than we think? (See Appendix A for a brief history of scepticism) On the other side of the discussion are the various groups of philosophers who have tried to prove that certainty is possible. These attempts have given birth to various theories of what knowledge is, how it can be guaranteed, etc., and the proper name for this aspect of philosophy is Epistemology (from the Greek episteme, meaning 'knowledge', and logos, meaning 'study of' or 'talk about'). What Will We Be Studying? In the following sections we will look at many of the main issues and problems in TOK and we will consider how philosophers over the ages have attempted to answer them. Throughout our survey we will always try and relate these problems to everyday life so as to make the ideas more real. Although this will sometimes be difficult or not always possible, most of the time it will allow us to clarify and understand the theories better. Some of the main issues we will be covering are: · · · · What possible reasons might make us doubt our knowledge? Is it possible to justify our knowledge with experience or rational proof? What is knowledge? Can it be defined? By what means do we come to know the world? At the end of each section there will be an assignment or questions to help you work through the ideas for yourself. Sometimes this will involve you doing some research and extra reading using the Internet, journals or books; sometimes it may involve making notes or answering questions on a video you have been asked to watch; sometimes it may involve simply sitting down and trying to question your own experience so that you can establish your own viewpoint. Introduction There are many points in our daily life where we might be mistaken about things or have cause to doubt them. As an exercise, I want you to think about the types of mistake that are possible and what that mistake is due to. So, for instance, I might think that today is Tuesday, when it is actually Thursday, which I could consider a lapse of memory. Set your answers out in a table like this: Mistake Thinking it is Tuesday not Thursday Mathematical mistake (42 + 59 = 111) Reason Lapse of Memory Faulty Reasoning Try and cover as many different types of mistake as you can think of (there is no need to list more than one example for each type - confusing Tuesday and Thursday is an example of faulty memory, so there is no need to list other examples). Once you have done this, turn the page. AS philosophy Copyright © G.J. Southwell, 2003 Page 1 of 11 Theory of Knowledge – Unit 1 – Scepticism The Sources of Knowledge Now, look through your list. How does it compare to mine? Mistake Thinking it is Tuesday not Thursday Mathematical mistake (42 + 59 = 111) Mistook a flying paper bag for a bird Thought I heard the doorbell ring Thought I smelt burning Felt as if something was crawling up my arm Dreamed that I won the lottery Accepted that Father Christmas is real Thought that Canada was a continent Feeling of familiarity in unfamiliar place Reason Lapse of Memory Faulty Reasoning Visual hallucination Auditory hallucination Olfactory hallucination Tactile hallucination Dream (sleeping hallucination) False trust Misheard, confused, misinformed Déjà vu (false internal conviction) Do you have any that aren't on my list? Or have you missed out some that I have mentioned? Of course, the reasons for the different types of mistake might be different to the answers I have given. Some might argue that Déjà vu, for instance, is a form of ESP (Extra Sensory Perception, or psychic ability), or even evidence of reincarnation or past life memories. From the point of view of the sceptic, the reason for the mistake is not so important as the fact that the mistake itself is possible. Looking down the list you may also note that most of the errors listed are due to some limitation in our sensory apparatus (our eyes, ears, etc.). This is not really surprising in that almost all of our knowledge - arguably - comes through them at one time or another. AS philosophy Copyright © G.J. Southwell, 2003 Page 2 of 11 Theory of Knowledge – Unit 1 – Scepticism The arguments from illusion and deception Most people don't really question their senses, but most people are also familiar with the types of mistake reported above. Why, then, aren't we more sceptical of the information coming through our senses? For convenience, we can categorise the type of error under four main headings: 1. Optical illusions These are traditional examples of diagrams, pictures, models, etc., which seem to provide odd effects on the senses. Look at the following pictures and note what you think this could tell us about our senses: (a) The Grid Stare at the grid below for a few seconds. Can you notice anything strange happening? (b) Sloping lines Look at the picture below of sloping lines. Or are they? AS philosophy Copyright © G.J. Southwell, 2003 Page 3 of 11 Theory of Knowledge – Unit 1 – Scepticism (c) Ascending and descending Are the monks walking up or down? (Drawing by M.C.Escher) (d) Old or young woman? Can you see more than one face here? For further examples of illusions see: http://www.optillusions.com 2. Delusions, waking dreams and visions. There is, as you might guess, a great deal of debate as to whether visions - in the religious sense - actually exist. However, setting this issue aside for the moment, it is possible to classify certain experiences as delusional. For example, someone who is running a fever, has suddenly woken from a deep sleep, is exhausted through hunger or fatigue, or even under extreme stress, may hallucinate. We may also include here certain types of mental illness where voices are heard or things projected out onto the outside world so that they appear as real (whatever that is! We AS philosophy Copyright © G.J. Southwell, 2003 Page 4 of 11 Theory of Knowledge – Unit 1 – Scepticism shall come back to this later). However, the main thing to notice here is that the mind is capable of producing illusions under certain circumstances. 3. Natural illusions The types of thing included here would be such things as: moisture rising from the ground appearing as a pool of water (a mirage); the light of a star that has by now died but can still be seen; a stick in water that looks bent; the way the moon looks bigger nearer to the horizon. These, and other examples, are often cited as proof that the senses cannot in themselves be trusted. As with the optical illusions (above), there seems to be a natural tendency to misinterpret, or provide misleading information regarding certain experiences. 4. Relative or subjective sensations Hot water to a cold hand can feel hotter than to a warm hand - and vice versa. Also, people who have had a limb amputated sometimes still have sensations where the limb was. Experiences of this type suggest that even something as fundamental as our bodily sensations can be mistaken. This is an especially strong point for the sceptic because our sense of touch is very often seen as being the most reliable, the thing most capable of giving us proof. If we can touch or feel something we are more likely to accept it as real than if we have merely seen it. How far can Scepticism go? So far we have considered ordinary doubts that people may suffer from in the course of their everyday existence. However, we now come to the thorny question of to what extent it is possible for there to be such a thing as "global" scepticism - that is, doubt about everything which we experience. To illustrate this it is necessary to distinguish between ordinary doubt and what is called "philosophical doubt". We all experience ordinary doubt: "Did I leave the iron on?", "Is Jim in a mood with me?", etc. These doubts are doubts about facts. If I go back home, I can check if the iron is still on; if I talk to Jim, I may find out if I have done something to offend him. Philosophical doubts are different. In the above situations, examples of philosophical doubts would be: is it possible to really tell if the iron is on; can I really find out if Jim is angry with me - or even more radically, if Jim is actually there (and not some figment of my imagination - or a robot!). Type of Doubt Example Local scepticism (also called "ordinary doubt") Is that a bird or a plane? Global scepticism (also called "philosophical Are my senses mistaken all the time? doubt") Before moving on, have a think about this difference and try to get it clear in your head. Ordinary doubt - or local scepticism - can usually be tested - and even when it can't, there may well come a time when it can. So, I may currently have doubts about whether there is life on some distant planet; however, in the future, technology may eventually allow me to actually find out (the development of a more powerful telescope, for instance). However, philosophical doubt - or global scepticism - seems to deny the possibility of there being any conclusive way of finding out. For instance, if in regard to the question of life on some other planet someone argued, "We can never really know that there is not life on another planet because it may be undetectable to us," then that person is a sceptic. AS philosophy Copyright © G.J. Southwell, 2003 Page 5 of 11 Theory of Knowledge – Unit 1 – Scepticism This sort of doubt is largely responsible for the reputation which philosophy seems to have in some quarters of being absurd and unrealistic. "Do you think that table is really there?" the philosopher asks. "You think you are talking to me, but what proof do you have?" However, the underlying point is a serious one: how can we ever really know something with absolute certainty? Remember, no matter how certain we are, there is always room for doubt. Even something like science, which uses experiment to prove theories, sometimes finds new truths which seem to contradict old ones (Einstein's theory of Relativity, for example). In summary, scepticism attacks certain beliefs that most of us hold to be true: It is sometimes possible to be certain about something. Our senses are mostly trustworthy. We can eventually find out whether we have been mistaken or not. It is possible to experience reality as it really is. Exercise Before moving on to the next section, I want you to do two things. Firstly, make a list of what you think are sceptical arguments (you can base them on the examples I have already given, but try to think of your own - 3 or 4 should do). Secondly, try to identify answers that you think a non-sceptic could use to show that these problems do not exist. Is it possible to do it? AS philosophy Copyright © G.J. Southwell, 2003 Page 6 of 11 Theory of Knowledge – Unit 1 – Scepticism Counter Arguments So, what would it be like to be completely mistaken about everything? When I see a mirage I can eventually find out that I was wrong to think there was a pool of water there. But if I question my ability to check that fact - that is, to put my mistake right - where does this leave me? Some philosophers have attempted to argue against this point by pointing out how the concept of a mistake only makes sense if it is possible to not be mistaken. D. Z. Phillips, in his book Introducing Philosophy, lists 3 counter arguments to philosophical doubt: i. The mistakes we make with regard to the senses seem to take for granted the accuracy of some of the sensory information. When we see a mirage, we do not doubt that the ground is there; when we mistake someone's voice on the phone, we do not doubt that someone is speaking. ii. Philosophical doubt seems to ignore the fact that these errors form part of the way we see the world. What would it be like for a straight stick not to appear bent in water? Or to see clearly in a fog? iii. Most of the examples given by sceptics involve unfavourable conditions: tiredness leads to hallucination or a mistake; something is seen fleetingly or at a distance; a fog obscures our vision. However, when these circumstances change, we realise our mistake. We rub our eyes, and the illusion disappears. We go closer, and we see clearly what we could not make out at a distance. We wait, and the fog lifts. Despite these counter-arguments, sceptical arguments persist. In fact, some philosophers have argued that it is impossible to prove the sceptic wrong, so we should just accept it and move on. However, before we do that, we are going to look at another form of scepticism: the argument from dreaming. The Argument from dreaming Most of what we have covered so far has dealt with the untrustworthiness of the senses. However, certain philosophers have taken the problem a stage further by asking the question, "Is it possible to tell reality from a dream?" The basis for this question is simple: when we dream we often believe that what we are experiencing is real. So, how can we be sure that what we are now experiencing is not a dream of some sort? The 17th century French philosopher René Descartes (1596-1650) most famously asked this question in his Meditations on the First Philosophy . However, the idea itself is not a new one. Many cultures contain stories and belief systems that portray life as a dream. Hinduism, most notably, considers all material existence to be illusory, or "maya", from which we "wake up" when we realise the true reality. Descartes had a similar agenda, though his intention was to establish beyond doubt that we are not deceived in any way - which dreaming would be an example of. The argument itself is not so easy to refute as you would think. To someone who replies that the argument can be easily refuted by the simple fact that we wake up, it can be AS philosophy Copyright © G.J. Southwell, 2003 Page 7 of 11 Theory of Knowledge – Unit 1 – Scepticism pointed out that there are occasions when people seem to have dreamed of doing that. This involves us in what is called an "infinite regress": anything which is mentioned as being an aspect of reality (as opposed to a dream) is said to be part of the content of the dream itself. So, I may dream that I think I am awake; I may dream that I can tell waking from dreaming; and so on. Descartes' answer to this problem is to try to guarantee knowledge through appeals to God and rational necessity (we shall look at this in more detail later in the course). However, other philosophers have put forward arguments based upon the idea that dreaming and waking up are concepts that are tied together (you cannot have one without the other). eXistenZ The idea of never waking up has been used by writers and film makers a number of times. Jacob's Ladder (1990) provides an original twist to this sort of story, and the 1999 film by David Cronenberg, called eXistenZ, uses the modern day equivalent of virtual reality games, with the tag line, "Where does reality stop... and the game begin?" Exercise In Shakespeare's Hamlet, the Prince of Denmark says: O God, I could be bounded in a nut shell and count myself a king of infinite space, were it not that I have bad dreams. (II. ii. 254-6) Here the idea seems to be that dreams provide some sort of link to - or proof of - the existence of the outside world. Consider to what extent this may be true. Is it possible that you are dreaming right now? What arguments might be used against someone who thought that life is a dream or illusion? As you consider these issues, make a list of arguments for the argument (life may be a dream) and against it (dreams and reality are different and easily distinguished). Which side wins? Try and make it like a real argument where the points follow on from one another. For Example: For Dreams seem real when we are dreaming Real life is sometimes fragmented and strange Against When compared to real life, dreams seem fragmented But not always Once you have done this, move on to the next section. AS philosophy Copyright © G.J. Southwell, 2003 Page 8 of 11 Theory of Knowledge – Unit 1 – Scepticism Other Arguments Brains in Vats The recent films The Matrix (1999) and The Matrix Reloaded (2003) , starring Keanu Reeves, imagines a situation where human beings are deceived on a mass scale by artificially intelligent machines to believe that they are living a normal life. However, they are actually living in a massive hive of incubators, providing energy for the machines whilst hooked up to a virtual reality replica of the real world. This is similar to what is called by philosophers the "Brains in Vats" argument, where it is supposed that the world as we know it is actually technologically generated and fed into our brain, which sits hooked up to wires in a vat of chemicals, devoid of a body. (A lot has been written about the connections between philosophy and the themes of the films. Anyone interested in exploring further should get hold of a copy of The Matrix and Philosophy: Welcome to the Desert of the Real (Open Court, 2002), edited by William Irwin. The official Matrix website also has a section dedicated to philosophical themes explored in the films written by actual philosophers - go to www.whatisthematrix.com and choose Philosophy from the Mainframe menu. Be careful, though: not all the material - in the book or website - is suitable for a beginner.) Worlds of Robots, Aliens and Hollywood Executives Other variations on this argument include the idea that human-looking machines are trying to pass themselves off as humans (Blade Runner, 1982), that the world is maintained by an alien race (Dark City, 1998) or even that a whole community of actors has been set up as a back-drop for the televised activities of one man (The Truman Show, 1998). Whatever the plot details, the story is generally the same: systematic deception on a massive scale. Modern variations of the story have tended to include advancements in technology that would allow such deception - such as virtual reality, robotics, etc. - but the idea itself is independent of the technological means. What is important is not so much whether such a deception is possible, but how could we tell? Witnesses and Testimony This leads us nicely into our next topic - that of knowledge at second hand. Once again, doubt concerning this sort of knowledge can be divided into what I shall call "local" and "global" scepticism. Local scepticism concerning the statements and behaviour of other people is common: "I think he's lying", "I don't believe her", "I don't trust them". We are quite use to being sceptical (with a small 's') about certain things: "He said he'd swum the Channel, but I was sceptical". However, so-called "global" scepticism about such things is a great deal more ambitious, and approaches the sort of scenario we come across in the films listed above. Imagine if everyone was deceiving you all the time, would you actually know what truth was? Exercise Despite the unlikelihood of being in something like The Truman Show, we cannot deny that a great deal of our information comes at second hand and from distant sources. Is there any knowledge, in fact, which does not come to us from second hand sources? How much do we actually experience at first hand? As an exercise, make a list of statements of different sorts - such as, "I know the world is round", "I know Man landed on the moon", "I AS philosophy Copyright © G.J. Southwell, 2003 Page 9 of 11 Theory of Knowledge – Unit 1 – Scepticism know grass is green" (choose about 5). Now, try to identify where this knowledge comes from. How much of it - if any - is second-hand? How much is first-hand? Which is more certain? Assignment In this unit we have looked at: · The nature of scepticism · How the senses may deceive us · Arguments for illusion, deception and dreaming · The difference between ordinary and philosophical doubt (Local and global scepticism) · Brains in vats, alien takeovers and Hollywood conspiracies Assignment for Unit 1 Choose one essay title from the following two past paper questions. Although you will not be ready to answer the whole question just yet - there are a few more things we need to cover - you can make a start on it by sketching out some ideas. There is an upper word limit of 1500 words, and a lower limit of 600. 1. Examine the extent to which sceptical arguments prevent us from claiming knowledge about the recent and distant past. 2. Assess the implications of the argument from illusion for our knowledge of the external world. AS philosophy Copyright © G.J. Southwell, 2003 Page 10 of 11 Theory of Knowledge – Unit 1 – Scepticism Appendix A: Brief History of Scepticism Scepticism (from the Greek, skeptesthai, 'to examine') is the philosophical view that it is impossible to know anything with absolute certainty, or to know the world as it 'really' is. The word can also mean a general reluctance to accept anything on face value without sufficient proof (as in "He heard that Jim had run the 100m in under ten seconds but he remained sceptical"). However, Scepticism (with a capital 'S') began in the 5th century BC in Greece where certain philosophers came to express doubts about how certain we could be about our knowledge. Protagoras of Abdera (480-411 BC), for instance, is reported to have said that "man is the measure of all things" (i.e. that we make the world in our own image) and Gorgias (485-380 BC) that "nothing exists; if anything does exist, it cannot be known; if anything exists and can be known, it cannot be communicated". Many such thinkers arose from the group known as the Sophists, men who would hire their skills in debate and argument out to anyone for the right fee. From this point of view, this form of scepticism is based on the fact that with enough skill, any argument can sound convincing. Next came the Pyrrhonists, so called after Pyrrho of Elis, it's founder, who argued that since we can never know true reality we should refrain from making judgements. His pupil, Timon of Philius, followed this by adding that equally good arguments could be made for either side of any argument (so it was impossible to decide). The New Academy of the 2nd century BC, founded by Carneades (214-129 BC), taught only that some arguments were more probable than others. Later sceptics include Aenesidemus (1st century BC), who put forward ten arguments in support of the sceptical position, and the Greek physician Sextus Empiricus (3rd century AD), who argued the use of common sense over abstract theory. When we reach the Renaissance we can see the influence of Greek scepticism in such thinkers as the French essayist Michel de Montaigne (1553-1592), but the sceptical issues only fully resurfaced with the French philosopher René Descartes ( 1596-1650). Descartes attempted to use sceptical arguments in order to establish a firm ground for knowledge. So, Descartes reasoned, if we attempt to subject everything to doubt we will hopefully discover at some point if there is anything that cannot be doubted. This he claimed to achieve in his assertion that it is impossible to doubt that we are thinking beings - which proves that we exist ( 'Cogito, ergo sum', which is Latin for 'I think, therefore I am'). By employing this 'method of doubt', as he called it, Descartes merely used scepticism as a means to find something certain, and was not therefore actually a sceptic. The sceptical cause was once again championed by the Scottish empiricist philosopher David Hume (1711-1776), who argued that certain assumptions - such as the link between cause and effect, natural laws, the existence of God and the soul - were far from certain. What little we know that seems certain, Hume argued, was based on observation and habit as opposed to any logical or scientific necessity. The German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), influenced by Hume, set limits to human knowledge by arguing that certain things - such as if there was proof for God, or if the world had a beginning - did not make sense to be asked. The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) argued that objective knowledge did not actually exist, and his scepticism influenced in turn that of French Existentialists such as Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980). The American philosopher George Santayana (1863-1952), argued that all belief - even that in oneself - is irrational (even though it seems the most natural thing). Modern day philosophy, although it does not generally take extreme sceptical arguments very seriously, still retains the influence of earlier sceptical thinkers. AS philosophy Copyright © G.J. Southwell, 2003 Page 11 of 11