An effective treatment of psychosis with

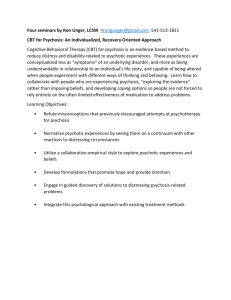

advertisement