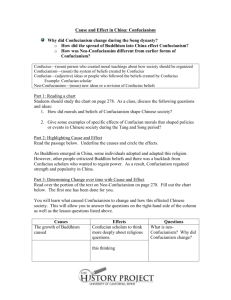

Confucius

advertisement

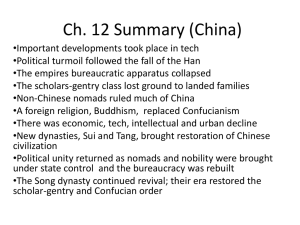

Confucianism America has been hampered in its efforts to bring its ideal of democracy and a free-market economy to certain areas of the world because of the unwillingness to understand the spiritual impact of Buddhism and Confucianism. If we are to understand the role of China as a superpower in the 21st century, we must appreciate the teachings of Confucius, which have shaped 2,500 years of Chinese history. Confucius played the same fundamental role in Chinese thought as the Buddha did in India, as Jesus did in the history of Europe, as Muhammad did in the Middle East, and as Socrates did in the intellectual life of Greece. Kong fu Tzu was born around 551BCE and died in 479 BCE making him a contemporary of the Buddha. The name by which he is most commonly known, Confucius, is a Latinized (actually Jesuit) form of Kong Fu Tzu, meaning Venerable Master Kong. Long after his death, the story of his birth began to circulate as wondrous tales. A unicorn came before his birth and presented his mother with a tablet announcing his birth. A pair of dragons and five ancient men, symbolizing the five directions, appeared in the heavens on the day he was born, and a celestial musical ensemble provided accompaniment for his birth. Not much is known of his youth other than his father died when Kong fu Tzu was three and his mother raised him under difficult circumstances. He married at 19 and had a son and daughter. His marriage was not a happy one and ended with the death of his wife. His son also died during Kong Fu Tzu’s life. At 22 he began the first of several jobs working for the government of his home state of Lu. He spent many years teaching privately and sought to win converts to his ethical and political views. While doing this, he held minor governmental positions, never gaining the public recognition he wished. At about the age 55, he went into a 13 year self-imposed exile, wandering in and out of nine Chinese provinces. He spent the last five years of his life studying and editing what were known as the Chinese Classics. The Master had a passion for fostering the kind of order in society that would offer genuine happiness. He had a simple moral and political code: to love others; to honor one’s parents; to do what is right instead of what gives you an advantage; to practice “reciprocity” (don’t do to others what you don’t want yourself); to rule by moral example instead of force or violence, etc. Kong fu zi taught that a ruler that had to resort to violence had already failed as a ruler. This wasn’t a principle Chinese leaders always followed, but it was the ideal of benevolent rule. He promoted the idea of the individual who would contribute to society through education, self-mastery and personal responsibility. His goals were political virtue and good government. “Confucianism” refers to a system of social, ethical, and religious beliefs and practices associated with Kong Fu Tzu. Even though there are temples dedicated to Confucius, the term does not imply the worship of Kong Fu Tzu as a supreme or central deity but it does acknowledge his pivotal role in the beliefs and practices that have been important in many Asian societies for over 2000 years. Kong Fu Tzu was not a religious leader; he believed in a divine order but refused to speculate about it. Chinese civilization during the time of Kong Fu Tzu was unusual in the classical period and beyond because its dominant values were secular rather than religious. Confucian teaching offers a great deal of reflection on the nature of an orderly society and methods of governing. In China, it became official government policy in the second century BCE and lasted all the way into the 20th century, and in Korea, Confucianism replaced Buddhism in the 14th century CE. In Japan, Confucian ideals influenced Japanese Imperial Rule from the 17th to the 19th centuries CE. Kong Fu Tzu saw himself as a spokesman for Chinese tradition and for what he believed were the great days of the Chinese state. He believed that if people could be taught to emphasize personal virtue, which included a reverence for tradition, a solid political life would naturally result. What is virtue? Do you know what it means to be virtuous? (having moral excellence/high standards of morality-being able to distinguish between right and wrong) The Confucian virtues stressed respect for one’s social superiors…including fathers and husbands as leaders of the family. Emphasis on this hierarchy was balanced by an insistence that society’s leaders behave modestly and without excess, shunning abusive power and treating all those in their care with courtesy. The subordinate member of the relationship had the duty of obedience to the superior. The only relationship that could be based on equality would be??? Friend to friend, unless one was much older than the other. Moderation of behavior, veneration for customs and tradition, and love of wisdom should characterize the leaders of society at all levels. This was quite different from India, where social obedience was absolute based on your caste. In India, a wife was supposed to obey and worship her husband even if he was lazy or worthless, unfaithful, abusive, etc. WHY? (because it was her karma to be in that kind of relationship) Under Confucianism, the highest duty was obedience to do what was right, and that meant you should disobey an order from a superior that caused you to do what was wrong. Of course, in the case of an order from the emperor, disobeying could get you killed. Confucius said one’s life has been worthwhile if one understands the way of truth. To follow the path of truth means to live your life in such a way as to make the world a better place; your life becomes a microcosm for the universe as a whole, which is perfect. In the search for the way to the truth Confucius said we must stand upon virtue and lean upon benevolence. Virtue consists of the same four moral qualities that are seen in Buddhism…wisdom, justice, courage, and moderation. Confucius believed in the natural goodness, or at least the in the possibility of perfectibility, of humans. This puts Confucianism in direct contrast to the Judeo/Christian heritage which maintains that humanity’s natural state is evil and that it needs divine intervention for salvation. Confucius believed that that under the right circumstances, it was possible for people to attain goodness and to eventually achieve the status of a superior human being. Confucian teachings describe the ideal society as one of “superior people.” To become a “superior person” an individual must have a high level of personal development through self-discipline and inquiry. The superior person values justice over profit, and prefers to be quiet and serene rather than vulgar and uncongenial (unfriendly or unpleasant). Cultivating a dignified manner, the superior person never the less avoids arrogance. Such a person looks to their own shortcomings rather than finding a way to blame others for their lack of understanding or appreciation. It is said the way of the superior person is a lengthy journey that begins from the “right here, right now.” Five “constant virtues” characterize the superior person: selfrespect, generosity, sincerity, responsibility, and openness to others. Behind this Confucian ideal of the superior person was the belief in the human potential for almost unlimited moral growth. Confucianism, sometimes called the Literati (Latin for “the lettered, educated”), was primarily a system of ethics—do unto others as your status and theirs dictates—and a plea for loyalty to the community. It reinforced the Chinese delight in learning and good manners. For both the ruler and the ruled, the emphasis was on individual virtuous behavior. “When the ruler does right, all men will imitate his self-control. What the ruler does, the people will follow.” The Literati also referred to the cultural and intellectual elite of China who preserved the Chinese imperial system. The Literati were the highly educated, professionally specialized bureaucrats who maintained the Chinese imperial government as China expanded and extended across much of Asia. For centuries, aspiring bureaucrats had to study the wisdom of Kong Fu Tzu and pass an exam in order to work for the Chinese Imperial government. The Chinese civil service was for well over 2000 years based on the wisdom of Kong Fu Tzu. Theoretically, if any man could pass the grueling exams, they would become a bureaucrat for the Chinese Imperial government, which was a highly sought after post. But the exams required hours of study and tutoring, something usually reserved for those who could afford it…meaning the sons of the affluent. For subordinates, Kong fu Tzu largely recommended obedience and respect; people should know their place, even under bad rulers. But unlike most, he didn’t believe in a political system which based rank purely on birth. He believed education should be available to all talented and intelligent members (male) of society. According to Confucius, force cannot permanently stop unrest, but kindness toward people and protection of their vital interests will. Rulers should also be humble and sincere, for people despise arrogance and hypocrisy. Nor should rulers be greedy, for true happiness rested in doing good for all, not in individual gain. Very soon after his death, the followers of Confucius initiated what would become a centuries-long process of elevating their teacher above the ranks of ordinary people. They revered him as a special ancestral figure, the pinnacle of wisdom. They built a temple in his honor in 478 BCE and not long after that began to enshrine statues and paintings of the Teacher. Official Imperial exaltation of Confucius didn’t begin for several centuries and it lasted until the early 20th century. In the year 1 CE the Han emperor Ping created a tradition that lasted until the 16th century by referring to Kong Fu Tzu in royal terms…he was known as “The Exalted Duke of the Highest Perfection.” A dozen later emperors followed, bestowing similar accolades on the Master. In the 16th century, emperors stopped using the language of royalty when speaking of Confucius and switched to titles that reflected wisdom like First Teacher, First Sage, High King of Learning, and Ultimate Sage. Even though he was never considered divine, Confucius was ranked by emperors and the people of China at the very zenith of human perfection. Not every Chinese emperor was happy with the wisdom of Confucius. In 213 BCE the Emperor Qin (Chin-a) accepted the recommendation of his prime minister, Li Si, and decreed that all books were to be destroyed, except those that were histories of this emperor’s dynasty. Li made this recommendation to strengthen the Emperor Qin’s authority because he believed the Confucian scholars had become too powerful and therefore threatened the emperor’s authority. All books of lyrics and poetry and every school of thought was to be brought to a local provincial governor to be burned. If you owned a book and didn’t bring it in to be destroyed within 30 days you had your face branded and you were sent to labor on the Great Wall for four years. Those who dared to talk about books were to be executed. Those who quoted the past (ie Confucian ideals) to criticize the present emperor were to be killed with their entire families. Those who knew of and didn’t report violations were to suffer the same punishment. The only books to be spared besides histories of the current Qin dynasty were books on medicine, divination, and tree- planting. Some Confucian scholars talked among themselves and accused the emperor of being power hungry, prone to kill and punish, and neglectful of intellectuals (violating the Mandate of Heaven). When the emperor learned of their dissent he ordered a thorough investigation. Frightened of the emperor, the scholars blamed each other rather than press their criticisms. It was discovered that over 460 scholars were involved, so the emperor order all 460 scholars buried alive in the capital. The first public schools The idea for the first public schools date back to ancient China. Confucius was among the first to advocate that primary school education should be made available to everyone. He promoted the idea that in education there should be no class distinctions. He personally never refused a student, no matter how poor. He firmly believed that any man, even a poor peasant, had the potential to be a man of principle. Unfortunately, this as not put into practice until recently. Where does Academic regalia come from? Nearly every student that graduates from high school or college makes a passing connection with the Confucian tradition. Academic robes with their wide flowing sleeves are similar to those worn by Confucian scholars, seen even today in places like Taiwan or Korea when they celebrate the Master’s birthday. But one look at the headgear, the “mortar board” and you’ll see the connection immediately. Participants in Confucian rituals wear large flat rectangular boards. Confucian mortar boards had rows of tassels all along the front and back, instead of the one tassel we use today.