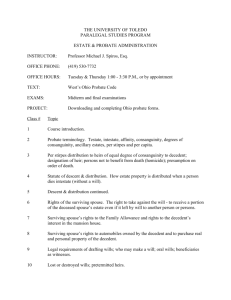

Trusts & Estates: Probate, Intestacy, Estate Planning

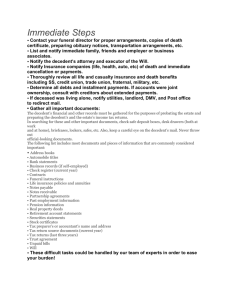

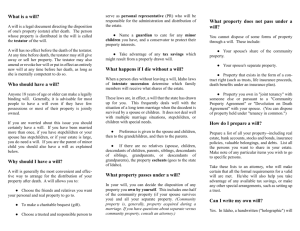

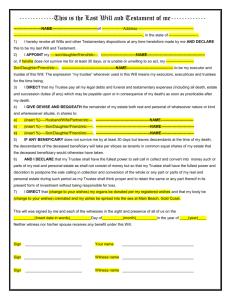

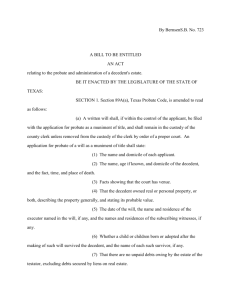

advertisement