Rinaldo v. McGovern - New York Injury Cases Blog

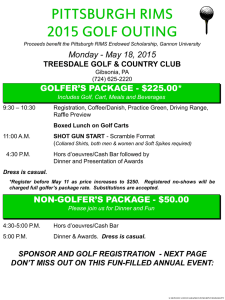

advertisement

587 N.E.2d 264 Page 1 78 N.Y.2d 729 (Cite as: 78 N.Y.2d 729, 587 N.E.2d 264) Roberta Rinaldo et al., Appellants, v. Arthur McGovern, Respondent, et al., Defendants. Court of Appeals of New York Argued October 16, 1991; Decided November 21, 1991 CITE TITLE AS: Rinaldo v McGovern SUMMARY Appeal from an order of the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court in the Fourth Judicial Department, entered November 16, 1990, which, with two Justices dissenting, affirmed an order of the Supreme Court (Thomas F. McGowan, J.), entered in Erie County, inter alia, granting a motion by defendant Arthur McGovern for summary judgment and dismissing the causes of action asserted against that defendant. Rinaldo v McGovern, 167 AD2d 942, affirmed. HEADNOTES Negligence--Duty--Mishit Golf Ball--Failure to Warn (1) In an action to recover for personal injuries sustained when defendant golfer accidentally missed the fairway and instead sent the ball soaring off the golf course onto an adjacent roadway where it struck the windshield of plaintiffs' automobile, plaintiffs' cause of action predicated upon a failure to warn was properly dismissed on defendant's motion for summary judgment. Under the circumstances of this case, a warning would have been all but futile. Even if defendant had shouted “fore”, the traditional golfer's warning, it is unlikely that plaintiffs would have heard, much less had the opportunity to act upon, the shouted warning. Accordingly, the possibility that a warning would have been effective to prevent the accident was simply too remote to justify submission of the case to the jury. Negligence--Duty--Mishit Golf Ball--Lack of Due Care (2) In an action to recover for personal injuries sustained when defendant golfer accidentally missed the fairway and instead sent the ball soaring off the golf course onto an adjacent roadway where it struck the windshield of plaintiffs' automobile, plaintiffs' negligence cause of action based on a purported lack of due care was properly dismissed on defendant's motion for summary judgment. Ordinarily, a golfer may not be held liable to individuals located entirely outside of the boundaries of a golf course who happen to be hit by a stray, mishit ball. To provide an actionable theory of liability, a person injured by a mishit golf ball must affirmatively show that the golfer failed to exercise due care by adducing proof, for example, that the golfer aimed so inaccurately as to unreasonably increase the risk of harm. However, in response to defendant's motion for summary judgment, plaintiffs submitted nothing more than the affidavit of a golf pro explaining that “slicing” is a common problem among inexperienced and experienced golfers alike, and a deposition statement to the effect that defendant had such a problem. At most, this evidence, if ultimately proven to be true, would establish only that if defendant teed off from the eleventh hole, there was a risk that his golf ball would travel off to the right in the direction of the road rather than the direction of the fairway. Plaintiffs' evidence did not, *730 however, show that defendant's actions with respect to this risk were negligent. TOTAL CLIENT SERVICE LIBRARY REFERENCES Am Jur 2d, Amusements and Exhibitions, § 87; Negligence, §§ 383- 385. NY Jur 2d, Negligence, §73. ANNOTATION REFERENCES Liability to one struck by golf ball. 53 ALR4th 282. POINTS OF COUNSEL John Humann for appellants. I. Plaintiffs, as travelers on a public highway, are entitled to be protected against acts on private premises which cause projectiles to come on to the public © 2009 Thomson Reuters/West. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works. 587 N.E.2d 264 Page 2 78 N.Y.2d 729 (Cite as: 78 N.Y.2d 729, 587 N.E.2d 264) highway. (Gleason v Hillcrest Golf Course, 148 Misc 246;Jenks v McGranaghan, 30 NY2d 475;Nussbaum v Lacopo, 27 NY2d 311;Noe v Park Country Club, 115 AD2d 230;Tinker v New York, Ontario & W. Ry. Co., 157 NY 312;Town of Albion v Ryan, 201 App Div 717;Palsgraf v Long Is. R. R. Co., 248 NY 339;Munsey v Webb, 231 US 150;Condran v Park & Tilford, 213 NY 341;Robert v United States Shipping Bd. Emergency Fleet Corp., 240 NY 474.) II. Summary judgment is a drastic remedy and should not be granted where there are issues of credibility or even a color of a triable issue. (Sillman v Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corp., 30 NY2d 395;Robinson v Strong Mem. Hosp., 98 AD2d 976;Goldstein v County of Monroe, 77 AD2d 232;Ugarriza v Schmeider, 46 NY2d 471;Callari v Pellitieri, 130 AD2d 935.) Chris G. Trapp for respondent. I. No duty existed to appellant. (Gleason v Hillcrest Golf Course, 148 Misc 246;Nussbaum v Lacopo, 27 NY2d 311;Jenks v McGranaghan, 30 NY2d 475;Noe v Park Country Club, 115 AD2d 230;Traumann v City of New York, 208 Misc 252.) II. Solely a question of law was presented. III. Summary judgment shall be granted where there is no issue of fact sufficient to require a trial. (Friends of Animals v Associated Fur Mfrs., 46 NY2d 1065;Zuckerman v City of New York, 49 NY2d 557;Fried v Bower & Gardner, 46 NY2d 765;Alvord & Swift v Muller Constr. Co., 46 NY2d 276;Platzman v American Totalisator Co., 45 NY2d 910;Andre v Pomeroy, 35 NY2d 361.)*731 OPINION OF THE COURT Titone, J. (1, 2) The issue in this appeal is whether a golfer who accidentally misses the fairway and instead sends the ball soaring off the golf course onto an adjacent roadway can be held liable in negligence for the resulting injury. Under the circumstances of this case, we hold that the defendant golfer incurred no tort liability for what amounted to nothing more than his poorly hit tee shot. The present action arises out of an accident in which a golf ball driven by one of the two individual defendants soared off the golf course on which they were playing, traveled through (or over) a screen of trees and landed on an adjacent public road, where plaintiffs happened to be driving their automobile. The ball struck and shattered plaintiffs' windshield, with the result that plaintiff Roberta Rinaldo was injured. It is undisputed that both defendants, who were teeing off at the eleventh hole of the golf course, intended to drive their balls straight down the fairway and not in the direction of the trees. However, each defendant “sliced” his ball, causing it to veer off to the right. There is no evidence that either defendant was careless or guilty of anything other than making an inept tee shot. Plaintiffs commenced the present action charging the individual defendants with negligence and failure to warn. On defendants' motion for summary judgment, the Supreme Court, Erie County, dismissed both causes of action, holding that defendants had no duty to warn plaintiffs of their impending tee shots and that defendants' conduct in mishitting their golf balls did not, without more, constitute actionable negligence. The Appellate Division affirmed, with two Justices dissenting. This appeal ensued (see,CPLR 5601 [a]). Plaintiffs also sued the operator of the golf course, Springville Country Club, Inc. By consent order dated May 6, 1991, plaintiffs' appeal with respect to this defendant, as well as to the individual defendant Donald Vogel, was discontinued. Accordingly, the only question before us now is the liability of the other individual defendant, Arthur McGovern. In general, a golfer preparing to drive a ball has no duty to warn persons “not in the intended line of flight on another tee or fairway” (Jenks v McGranaghan, 30 NY2d 475, 479;see generally, Annotation, Liability to One Struck by Golf Ball, 53 ALR4th 282). Even more to the point, whatever the extent of *732 a golfer's duty to other players in the immediate vicinity on the golf course (see, Johnston v Blanchard, 301 NY 599), a golfer ordinarily may not be held liable to individuals located entirely outside of the boundaries of the golf course who happen to be hit by a stray, mishit ball (see, Nussbaum v Lacopo, 27 NY2d 311, 318). In Nussbaum v Lacopo (supra), we considered the liability of a golfer for failing to warn the occupant of a nearby residence before driving his golf ball. In rejecting the injured resident's claim, we noted that the duty to warn “is imposed to prevent accidents” and that no such duty should be imposed where “the relationship between the failure to warn and [the] plaintiff's injuries is tenuous” (id., at 318). We concluded that imposing a duty to warn would be futile © 2009 Thomson Reuters/West. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works. 587 N.E.2d 264 Page 3 78 N.Y.2d 729 (Cite as: 78 N.Y.2d 729, 587 N.E.2d 264) under the circumstances presented in Nussbaum because “[l]iving so close to a golf course, plaintiff would necessarily hear numerous warning shouts each day ... [and, consequently,] could be expected to ignore them” (id., at 318). Plaintiffs contend that the analysis in Nussbaum is inapplicable to this case because the Nussbaum Court specifically stated that “one who chooses to reside on property abutting a golf course is not entitled to the same protection as the traveler on the public highway” (id., at 316 [emphasis supplied]), thereby suggesting that individuals in the latter class are entitled to special protection. Although plaintiffs, who were innocent travelers, hope to benefit from this distinction, their argument on this point is meritless. The dictum on which plaintiffs rely appears in the section of the Court's opinion dealing with the liability of the golf course for nuisance and negligent design.Whatever its legal significance in that category of cases, this dictum has no bearing on the viability of a claim such as this one, which was brought against an individual golfer on the basis of an alleged failure to warn. (1) Instead, the pertinent question here, as in Nussbaum, is whether a warning, if given, would have been effective in preventing the accident. We conclude that, under the circumstances of this case, a warning would have been all but futile, albeit for a somewhat different reason than in Nussbaum.Even if defendant had shouted “fore”, the traditional golfer's warning, it is unlikely that plaintiffs, who were driving in a vehicle on a nearby roadway, would have heard, much less had the opportunity to act upon, the shouted warning. Accordingly, *733 just as was true in Nussbaum, the possibility that a warning would have been effective here to prevent the accident was simply too “remote” to justify submission of the case to the jury (id., at 318). Plaintiffs' cause of action based on the claimed negligence of the defendant golfer is similarly untenable. Although the object of the game of golf is to drive the ball as cleanly and directly as possible toward its ultimate intended goal (the hole), the possibility that the ball will fly off in another direction is a risk inherent in the game. Contrary to the view of the dissenters below, the presence of such a risk does not, by itself, import tort liability (see,167 AD2d 942, 944 [Callahan, J. P., and Balio, J., dissenting]). The es- sence of tort liability is the failure to take reasonable steps, where possible, to minimize the chance of harm. Thus, to establish liability in tort, there must be both the existence of a recognizable risk and some basis for concluding that the harm flowing from the consummation of that risk was reasonably preventable. Since “ 'even the best professional golfers cannot avoid an occasional ”hook “ or ”slice“ ' ” (Jenks v McGranaghan, supra, at 479, quoting Nussbaum v Lacopo, supra, at 319), it cannot be said that the risk of a mishit golf ball is a fully preventable occurrence. To the contrary, even with the utmost concentration and the “tedious preparation” that often accompanies a golfer's shot (see, Nussbaum v Lacopo, supra, at 319), there is no guarantee that the ball will be lofted onto the correct path. For that reason, we have held that the mere fact that a golf ball did not travel in the intended direction does not establish a viable negligence claim (Jenks v McGranaghan, supra, at 479). To provide an actionable theory of liability, a person injured by a mishit golf ball must affirmatively show that the golfer failed to exercise due care by adducing proof, for example, that the golfer “aimed so inaccurately as to unreasonably increase the risk of harm” (Nussbaum v Lacopo, supra, at 319). (2) No such proof was adduced here. In response to defendants' motion for summary judgment, plaintiffs submitted nothing more than the affidavit of a golf pro explaining that “slicing” is a common problem among inexperienced and experienced golfers alike and a deposition statement by defendant Vogel to the effect that his codefendant, McGovern, had such a problem. At most, this evidence, if ultimately proven to be true, would establish only what is obvious--that if one or *734 both defendants teed off from the eleventh hole, there was a risk that one or both of their golf balls would travel off to the right in the direction of the road rather than the direction of the fairway. Plaintiffs' evidence did not, however, support the other element of the cause of action essential to plaintiffs' recovery, i.e., that defendant's actions with respect to this risk were negligent. Hence, plaintiffs' cause of action based on defendant's purported lack of due care was properly dismissed. Accordingly, the order of the Appellate Division should be affirmed, with costs. © 2009 Thomson Reuters/West. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works. 587 N.E.2d 264 Page 4 78 N.Y.2d 729 (Cite as: 78 N.Y.2d 729, 587 N.E.2d 264) Chief Judge Wachtler and Judges Simons, Kaye, Alexander, Hancock, Jr., and Bellacosa concur. Order affirmed, with costs. *735 Copr. (c) 2009, Secretary of State, State of New York N.Y. 1991. RINALDO v McGOVERN 78 N.Y.2d 729 END OF DOCUMENT © 2009 Thomson Reuters/West. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.