BENCHMARKING PHYSICIAN RECRUITING DEPARTMENTS

advertisement

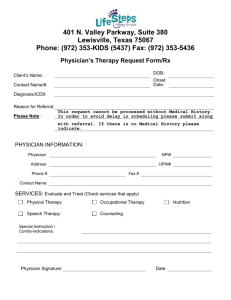

BENCHMARKING PHYSICIAN RECRUITING DEPARTMENTS by Tammy D. Jamison, Physician Recruiter, Lehigh Valley Hospital, Allentown, PA ASPR Newsletter, VOL. 8, NO. 4, Winter 2001 How would you react if your boss came to you and said, “I would like you to conduct a benchmarking study so that I can see how you and your department measure up in performance against your colleagues across the country?” Would you react with joy? Probably not. With trepidation? Perhaps. With curiosity? Probably. My first reaction was a throwback to adolescence with memories of standardized tests with #2 pencils. I don’t think it is unnatural to experience a little angst when being asked to compare yourself and your performance to others, regardless of the basis of comparison. However, once the initial trepidation subsided, curiosity took over and I really wanted to know how my performance and that of my department compared with other departments at hospitals across the country that are responsible for recruiting physicians. At my hospital, Lehigh Valley Hospital in Allentown, Pennsylvania, we had been engaged in benchmarking since 1996 as part of our ongoing Operations Improvement efforts. We contracted with MECON-PEERx, an operation benchmarking database service that has data from over 500 subscribing hospitals and a comprehensive analysis product. Through this initiative, we were provided with data from “cohorts” or a comparison group of hospitals on clinical and non-clinical departments to gauge productivity, cost performance, and cost position. The goal was to identify those hospitals and departments that have costs per unit of service placing them in the lower 25 percent among similar hospitals, and to learn from those organizations. However, there was no MECON data to extract and analyze on physician recruiting departments when we decided to embark on a benchmarking study for inhouse physician recruiting departments, so we decided to create our own template. This became a more arduous process than we had originally anticipated. In order to develop a substantial list of participants to which we could compare ourselves, we used two resources. We contacted a number of members of the Association of Staff Physician Recruiters (ASPR) who worked at hospitals of similar size to ours. We were able to identify hospitals of similar size by cross-referencing the ASPR directory with the American Hospital Association Guide. Recognizing that not all in-house recruiters are members of ASPR, we enhanced the size of our study group by using an in-house physician recruiter’s Internet chat room, which is supported by a website (Physicians Employment on the Internet, www.physemp.com) on which in-house physician recruiters can list available positions for physicians. Using this resource, we extended an open invitation to recruiters to participate in our benchmarking study. With the study group selected, we moved on to the next step. The most obvious indicator to compare is the number of resolved searches in a given year. However, we learned that the way in which different hospitals manage their recruitment processes blurred this somewhat basic concept for comparison. For example, some recruiters use search firms, and some don’t. Some recruiters do in-depth, hour-long screening interviews, and others ask a few pertinent questions of their candidates. Some recruiters just source candidates while others narrow the field, schedule on-site visits, host candidates, and work with families and relocations. Some recruiters have additional responsibilities within their organizations, such as credentialing or conducting mid-level provider searches, that takes time away from physician recruiting. Some recruiters have support staffs, and some don’t. All of these variables made it challenging to establish a baseline to use for comparison. We developed a list of questions that we believed were relevant to gather the information we needed to start our study. However, after the first several conversations, we began to identify even more variables, which forced us to refine and enhance our list of questions. What we asked of all the participants was: 1. What is the size of your hospital or network? (number of beds and hospitals) 2. How many in-house recruiters are in the department, and what are their responsibilities? 3. How many physicians did you recruit last fiscal or calendar year? 4. Of the number of physicians recruited, how many were hired with the assistance of a search firm? 5. How many physicians were recruited from your own hospital’s residency or fellowship programs? 6. Of the resolved searches, how many were for primary care physicians and how many were for subspecialists? 7. How many of your recruited physicians were international medical school graduates? 8. Does your department support physician and non-physician executive searches for your hospital or network? 9. What is your scope of responsibility within the search process, i.e., do you source, conduct in-depth telephone interviews, schedule site visits, meet with candidates on visits, provide community tours, work with spouses and families, assist with post-hire work such as finding temporary housing or employment opportunities for spouses, etc.? The reason we asked such a variety of questions was so that we could establish an accurate baseline for comparing our department to others across the country. For example, there is no question that recruiting a resident from your hospital’s own training program is much easier than recruiting a physician from another part of the country. Using search firms is an effective method of locating candidates, and that frees up the in-house recruiter’s time to focus on other aspects of the recruiting process. However, using a search firm does increase the cost of recruiting a physician. Also, while being asked to recruit a family physician to a rural community with a call schedule of 1:2 was a recipe for a migraine headache several years ago. In today’s market with the increased number of family practice residency programs, the available pool of family practice candidates is much larger and the competition for them much less intense. Now my head starts to ache when I’m asked to recruit a fellowship-trained laparoscopic urologist when I learn that only five fellows come out of training each year in North America! Also, we know it is generally much easier to recruit an international medical school graduate than a physician who is American schooled. All of these variables need to be factored in when making a comparison of in-house physician recruiting departments. We reached several conclusions through this benchmarking process. One is that benchmarking is not to be feared, but rather embraced because it can provide at least three very valuable benefits. First, by doing a benchmarking study, you have an incredible opportunity to learn from your recruiting colleagues – there are many different ways to accomplish our shared goal of recruiting physicians. Second, a benchmarking study is an effective way to measure your performance and can be used to demonstrate to your boss how effective you are in performing your job, a job in which performance is sometimes hard to quantify. Third, a benchmarking study can be used to validate your department’s existence. In these times of increasing financial pressures in healthcare, every department that is not involved in direct patient care may be asked at some time to substantiate the value the department adds to the hospital. Recruiting departments are not revenue generating entities, and thus may come under scrutiny at budget time. A progressive physician recruiting department should be well prepared to demonstrate the value it adds to the organization it serves and the money it saves that organization by keeping the recruiting function in house. The most important conclusion we reached, however, is that benchmarking needs to be an ongoing process. Trends within our industry are constantly changing, and those trends affect our ability to recruit. Further, there are other parameters we didn’t include in our study that we believe will be important to analyze in upcoming studies, such as average cost of a search, retention of recruited physicians, length of a search, and the ratio of offers made to offers accepted. This is important data to compile and analyze, and we hope our experience will inspire you to participate in a benchmarking study or to conduct one yourself. The chart we designed to document our findings is included on the next page, and may be helpful for you to use as a template for your benchmarking study. If you think this article is a call to action…it is!