Page | 1 The diffusion of antibiotics through the biofilm pores

advertisement

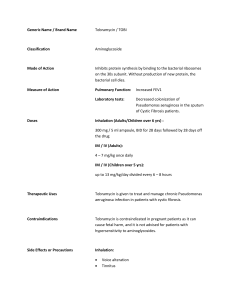

The diffusion of antibiotics through the biofilm pores produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa using a synthetic neutrophil extracellular trap Team Nanobots Mark Ly, Fahima Nakitende, and Shannon Wesley Theme: Nanoscience Subtheme: Nanoparticle systems for studying biomolecules Keywords: Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm, copper-oxide nanowire bundles, neutrophil extracellular trap, cystic fibrosis, ciprofloxacin/tobramycin Page |2 SUMMARY We intend to study Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacterial infections by using nanowires to deliver antibiotics across its biofilm for the treatment of chronic infections. Past research studied 40 patients suffering from cystic fibrosis disease, and determined 77% were infected by P. aeruginosa even though 71% of them were healthy (Neter 1974; Diaz et al. 1970; Diaz and Neter 1970). Antibiotic treatment by itself was ineffective against P. aeruginosa because of its protective biofilm. So, we intend to penetrate through the biofilm produced by P. aeruginosa using copper-oxide nanowire bundles (CuO NWBs) to help deliver antibiotics and destroy the bacteria residing inside the biofilm. P. aeruginosa form thick biofilms which guard them and prevent antibiotics from reaching the pathogen for destruction (Costerton et al. 1999; Nickel et al. 1985). The biofilm structure of P. aeruginosa is important because it consists of pores and channels that allow for the transport of nutrients required for growth. We plan to exploit this pore system and use diffusion as a way to penetrate through the biofilm (Costerton et al. 1999; Stewart 1996). Previous studies used ciprofloxacin and tobramycin antibiotics to treat P. aeruginosa biofilm infections but were ineffective (Walter et al. 2002). The antibiotics blocked the sites where the transport took place inside of the biofilm resulting in a lack of oxygen and low metabolic activity. To solve this problem, we propose to organize copper-oxide nanowires into nanowire bundles to form a synthetic mesh-like net. This net will provide a large surface area for antibiotic attachment as well as prevent the obstruction of the biofilm diffusion channels due to their nanometer size. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) were observed to be effective in binding and destroying bacterial cells, but are vulnerable to certain bacterial toxins (Brinkman 2004; Tirouvanziam 2007). We will attempt to use a synthetic NET composed of CuO NWBs to overcome this disadvantage. The aim of our study is to determine the effectiveness of ciprofloxacin and tobramycin coupled onto CuO NWBs against P. aeruginosa biofilm growth. We hypothesize that CuO NWBs carrying the antibiotics Page |3 will mimic a NET and penetrate through the biofilm to kill the pathogen from the inside. If this happens successfully, we expect to see no growth on the antibiotic/CuO NWBs agar plates. We will follow Harrison’s et al. (2006) procedure to grow our P. aeruginosa biofilms which will take three days to complete. Data collection will occur immediately to avoid biofilm degradation. We will purchase and use a de-protonated solution of ciprofloxacin and tobramycin antibiotics and follow the methods outlined by Li et al. (2010) to synthesize CuO NWBs. We will then use electrostatic interaction to couple these antibiotics to the CuO NWBs. We will prepare four treatments, each in 24 out of 96 wells of a MBEC plate and expose them to P. aeruginosa. Our treatments will consist of: our control (no antibiotic/no CuO NWBs), antibiotic only (ciprofloxacin or tobramycin), CuO NWBs only, and antibiotic/CuO NWBs. From this experiment, we will determine the mean amount of P. aeruginosa biofilm growth after being exposed to each treatment by using a one-way fixed effect ANOVA statistical test to compare the mean colony forming units (CFUs) for our three different treatments. We expect to see 100% growth of P. aeruginosa biofilms for the control and antibiotic treatment, limited growth for CuO NWBs treatment, and 0% growth for the treatment of antibiotic/CuO NWBs. If our experimental results correlate with the above expected results, then our synNETs can be used as an alternative therapy for P. aeruginosa biofilm infections. Also for future studies, determination of the optimal concentration of CuO NWBs without antibiotics needed to effectively kill P. aeruginosa biofilm growth would be necessary. Page |4 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND We propose to study the control of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections by using nanowires to deliver antibiotics across the P. aeruginosa’s biofilm to treat chronic infections. According to previous research, among 40 patients suffering from cystic fibrosis, 77% were infected by P. aeruginosa, even though 71% of these patients exhibited a normal immune response (Neter 1974; Diaz et al. 1970; Diaz and Neter 1970). Consequently, conventional antibiotic therapy was ineffective against the P. aeruginosa infection. Thus, we propose to use copper-oxide nanowire bundles (CuO NWB) to penetrate the biofilm produced by P. aeruginosa to deliver antibiotics and kill the bacteria residing inside the biofilm. Cystic fibrosis is an inherited disease that causes a thick, sticky mucus build up in the lungs, which is an ideal environment for P. aeruginosa biofilms to flourish (Moskowitz et al. 2008). P. aeruginosa infections form biofilms to defend themselves against human immunity and conventional antibiotic therapy (Costerton et al. 1999; Nickel et al. 1985). This is important because a P. aeruginosa’s biofilm forms a 200 µm barrier of sugars and carbohydrates to prevent antibiotics from reaching the pathogens (Hanlon et al. 2001; Anwar and Costerton 1992; Costerton et al. 1987; Govan and Deretic 1996). Earlier studies have used diffusion as a way to enter the pathogen’s biofilm layer to kill it, which is the method we propose to use in our study. This is because the structure of P. aeruginosa’s biofilm consists of numerous pores and channels, which can be used for the diffusion of nanowires (Costerton et al. 1999; Stewart 1996). Nanowires have been used in various biological applications due to their size and selectivity (Li et al. 2010; Bao et al. 2008; Lu et al. 2007). These wires have a diameter of the nanometer scale, which can have different shapes and properties depending on the material they are made of. Furthermore, we can arrange these nanowires into nanowire bundles to form a synthetic mesh-like net that will increase the available surface area for antibiotic attachment. Metal ions have been used by Harrison et al. (2005) to kill the pathogen by diffusing metal ions through the P. aeruginos’s biofilm. In addition, the results showed that a high concentration and long exposure time of Page |5 various metal ions were able to completely eliminate the biofilm. In addition, lengthy exposure time was a result of cationic binding of the metal ions to the biofilm that restricted the rate of penetration. Harrison et al. (2005) also determined that 40 mM of lead, 120 mM of zinc, 140 mM of cobalt and nickel, and 300 mM of aluminum metal ions were required to destroy a biofilm, whereas only 30 mM of copper was required to have the same outcome. Thus, we decided to make our nanowires out of copper because copper was effective at low concentrations and non toxic to biological systems relative to lead. We will attempt to use electrostatics to bind antibiotics to our CuO NWB carriers. We predict the antibiotics will occupy the positive charge on the CuO NWBs and will not adhere to the surface of the biofilm during diffusion. Previous research performed by Walters et al. (2002) demonstrated tobramycin and ciprofloxacin eventually penetrated the biofilm, but failed to kill P. aeruginosa once inside the biofilm. As indicated by Figure 1, both ciprofloxacin and tobramycin did not increase P. aeruginosa’s mortality rate over a 100 hour exposure time. Figure 1. Killing of P. aeruginosa in biofilms in exposure to ciprofloxacin (A) and killing of P. aeruginosa in biofilms in exposure to tobramycin (B). Filled squares were the treatment and the unfilled were the controls (Walter et al. 2002) Thus, the ineffectiveness of these antibiotics was not because of poor penetration, but oxygen limitation and low metabolic activity inside the biofilm. A lack of oxygen within the biofilm either prevented P. aeruginosa growth or the action of the antibiotics; whereas, free swimming bacterial cells were susceptible to tobramycin and ciprofloxacin. For these reasons, we decided to use these two antibiotics in conjunction with Page |6 our CuO NWBs to kill the pathogen inside the biofilm. These bundles will not block the P. aeruginosa biofilm pores because of their nanometer size. Therefore, oxygen transport will be restored, metabolic activity will continue as normal, and we will be able to spread the antibiotics over a larger area. So, by combining these antibiotics to our CuO NWBs we are creating a synthetic neutrophil extracellular trap (synNET). According to Brinkmann et al. (2004), white blood cells in a normal immune response form a neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) by secreting proteins and chromatin as shown in Figure 2. This NET traps the pathogen and prevents damage to the adjacent tissues at the site of infection. NETs bind to bacterial cells, prevent the spread of infection, and kill the pathogen using antimicrobial agents (toxins, chemicals, or antibodies) (Weinrauch et al. 2002). As a result of these above advantageous properties, we will use a bundle of nanowires to imitate a NET and trap the pathogen. According to Tirouvanziam et al. (2007), NETs are rapidly killed by toxins released by the bacterial cells making them ineffective. This is why patients with cystic fibrosis are continuously suffering from recurring episodes of P. aeruginosa infection. So, could CuO NWBs carrying antibiotics diffuse through the porous structure of P. aeruginosa’s biofilm and act as a synNET? We hypothesize that CuO NWBs will imitate a NET and carry antibiotics through the biofilm of P. aeruginosa to kill the pathogen from the inside. If this synNET carrying antibiotics successfully diffuses through the biofilm, we predict no growth on the antibiotic/CuO NWB agar plates. Figure 2. Neutrophil extracellular trap (NET). Page |7 PROPOSED RESEARCH The aim of our study is to determine the effectiveness of ciprofloxacin and tobramycin coupled CuO NWBs against Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm growth. We will grow P. aeruginosa biofilms every three days to avoid biofilm degradation which usually occurs at about 48 hours and to ensure a constant 24 hour aged biofilm for testing (D. Storey, pers. Commun.). Also, we will synthesize one set of CuO NWBs for each antibiotic. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilm Synthesis We will follow Harrison’s et al. (2006) procedure shown in Figure 3 to grow P. aeruginosa biofilms using the Calgary Biofilm Device (CBD) with the exception of using the scanning electron microscopy method. Figure 3. The experimental design to synthesize P. aeruginosa biofilms, using Luria-Burtani Broth (LB) and the Calgary Biofilm Device (CBD) system; and examination of the biofilm’s structure using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) equipment (Harrison et al., 2006). Scanning electron microscopy will not be performed. A confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) and its 3D imaging properties will be used to examine the biofilm’s structure and confirm the presence of pores. Only biofilm structures containing pores will be used in this research study to make sure diffusion transport is accessible. Page |8 Ciprofloxacin and Tobramycin We will purchase 100 mg of deprotonated (negatively charged) ciprofloxacin and tobramycin from Sigma-Aldrich. Walter’s et al. (2002) procedure will be used to test ciprofloxacin and tobramycin against P. aeruginosa biofilms as our control. This will ensure that these two antibiotics are independently ineffective against P. aeruginosa biofilms. Synthesis of CuO NWBs We will follow the methods outlined by Li et al. (2010) to synthesize the CuO NWBs. We will create nanowires and combine it with an aqueous solution of CuCl2. This composite solution will be vacuum filtered and dried in an oven to produce our nanowires CuO NWBs. The initial template will be removed with a solution of NaOH and the CuO NWBs will dry a final time. Creating our CuO NWBs will take 24 hours to complete. We will determine the structure and correct chemical composition of our CuO NWBs by using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and X-ray diffraction (XRD). This will guarantee our CuO NWBs self assembled correctly. Synthesis of synNETs To attach our antibiotics, we will use electrostatic interactions (CuO NWBs positive charge with the antibiotics negative charge) to couple with our CuO NWBs. A solution of ciprofloxacin/tobramycin will be cast onto the CuO NWBs separately and then slowly evaporated to produce our synNETs. These synNETs will be stored in a refrigerator (4 ). We will follow Li’s et al. (2010) characterization method to characterize our synNET. Fourier transform-IR (FT-IR) spectra will be performed using a Nicolet Avatar mass spectrometer from the University of Calgary’s Chemical Instrumentation Facility to compare three different peaks: the CuO NWBs individually, the antibiotic individually, and the antibiotic coupled with our CuO NWBs. If our antibiotics coupled with our CuO NWBs successfully, we expect to see a spectra that is a combination of both individual peaks: CuO NWBs and antibiotic. Page |9 One factor that could affect our results is the strength of the electrostatic interaction between the antibiotics and the CuO NWBs. If the interaction is too weak then the CuO NWB may attach to the biofilm layer instead of the antibiotic, and the CuO NWB will not deliver the antibiotic across the biofilm layer. Controls and Test Samples P. aeruginosa biofilms in 96 welled MBEC plates will be randomly exposed to each parameter listed in Table 1 below: Table 1. Experimental group parameters tested with P. aeruginosa biofilms. TREATMENT A Control B Antibiotic only C Nanowire only D Nanowire + Antibiotic EXPERIMENTAL TREATMENT PARAMETERS No antibiotic No copper-oxide nanowire Antibiotic No copper-oxide nanowire No antibiotic Copper-oxide nanowire Antibiotic fused Copper-oxide nanowire EXPECTED RESULT Growth Growth Limited growth (copper-oxide toxicity) No growth (antibiotic penetration) To prepare each of our test group parameters in Table 1 above, we will follow the procedures outlined in Table 2 below: Table 2. Experimental treatment group preparations. A TREATMENT Control B Antibiotic only C Nanowire only D Nanowire + Antibiotic PREPARATION PROCEDURE Add 200 µL of 0.9% NaCl to 24 wells of a 96-well MBEC plate of a randomly selected region (A,B,C, and D) (Fig. 4) Add 200 µL of antibiotic to 24 wells of a 96-well MBEC plate of a randomly selected region (A,B,C, and D) (Fig. 4) Add CuO NWBs to 24 wells of a 96-well MBEC plate containing 200 µL of 0.9% NaCl of a randomly selected region (A,B,C, and D) (Fig. 4) Add 200 µL of diluted antibiotic fused copper-oxide nanowires to 24 wells of a 96-well microtiter plate of randomly selected regions (A,B,C, and D) (Fig. 4) P a g e | 10 Figure 4. A MBEC plate illustrating the regions of the treatment parameters: control, antibiotic only, nanowire only, and antibiotic coupled CuO NWBs. Each treatment will consist of 24 out of the 96 wells and will be rotated between regions A, B, C, and D (Ceri et al. 1999). Experimental Procedure The first day we will grow P. aeruginosa biofilms and synthesize CuO NWBs. Then, we will routinely repeat the following 3 day outline for the duration of our 8 month experimentation with 2 days of intermittent data collection. Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 - Confirm P. aeruginosa biofilm growth using CLSM and collect A treatment results Confirm the presence of copper on the CuO NWBs using TEM & XRD Synthesize ciprofloxacin and tobramycin coupled CuO NWBs Confirm proper coupling using FT-IR Start B treatment and incubate 24 hours (35 ) - Sonicate biofilm pegs, start C treatment, and incubate 24 hours (35 ) - Sonicate biofilm pegs, start D treatment, and incubate 24 hours (35 ) - Collect B treatment results - Collect C treatment results Collect D treatment results Grow P. aeruginosa biofilms - P a g e | 11 Sample Size We expect limited growth once we penetrate the biofilm layer of P. aeruginosa with our synNET. To determine the sample size (N) we will use a chi-squared logistical model to determine the noncentrality parameter (λ) using the formula N = λ / w2. The effect size (w) is the effect we are interested in detecting. With our growth and no growth model we expect to see a medium effect size of 0.3. With 14 degrees of freedom in our experimental design, we obtained a noncentrality parameter of 27.2. The sample size that is required for our experiment is 303. Thus, we will need at least 13 MBEC plates to get the required sample size. Analysis and Interpretation Harrison’s et al. (2006) viable cell counting procedure will be used to determine the mean amount of P. aeruginosa biofilm growth after being exposed to three different treatments (Fig. 5). In addition, we will separate our LB agar plates into four sections to allow us to examine all 4 treatments simultaneously. Figure 5. Diagram of experimental procedure used for group tests B, C, and D (Table 1). Step D above will incubate with antibiotics for group tests B and D and with CuO NWBs for group tests C and D (Herrmann et al., 2010). No dilution will be preformed since we are performing a qualitative analysis. P a g e | 12 From our collected data, a one-way fixed effect ANOVA statistical test will be performed to compare the mean colony forming units (CFUs) for our three different treatments. The ANOVA statistical test will determine any growth differences between our antibiotic only, CuO NWBs only, and synNETs. Our expected results from the ANOVA statistical test should reveal 100% growth in the control and antibiotic only treatments, less than 100% growth in the CuO NWBs only treatment, and 0% growth in the antibiotic coupled CuO NWBs treatment (Fig. 6). If our experimental results correlate with our expected results presented above, then our synNETs can be used as an alternative therapy for P. aeruginosa biofilm infections. In addition, future studies could be conducted to determine the optimum concentration of CuO NWBs (without using antibiotic coupling) needed to effectively kill P. aeruginosa biofilm growth. Figure 6. The expected results for each of the treatments applied in our experiment. The average CFU count for our control and CuO NWBs only will consist of information from 630 samples. The average CFU count of both treatments involving our antibiotics will consist of 315 samples for each antibiotic for a combined 630 samples. The results from our antibiotic and combination treatments will consist of a combination of results from our separate ciprofloxacin and tobramycin tests. P a g e | 13 LITERATURE CITED Anwar H, Costerton JW. 1992. Effective use of antibiotics in the treatment of biofilm-associated infections. American Society for Microbiology News. 58: 665–668. Bao SJ, Li CM, Zang JF, Cui XQ, Qiao Y, Guo J. 2008. New nanostructured TiO2 for direct electrochemistry and glucose sensor applications. Advanced Functional Materials. 18: 591-599. Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, UhlemannY, Weiss SD, Weinrauch Y, Zychlinsky A. 2004. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 303: 15321535. Ceri H, Olson ME, Stremick C, Read RR, Morck D, Buret A. 1999. The Calgary biofilm device: New technology for rapid determination of antibiotic susceptibilities of bacterial biofilms. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 37:1771-1776. Costerton JW, Cheng KJ, Geesey GG, Ladd TI, Nickel JC, Dasgupta M, Marrie TJ. 1987. Bacterial biofilms in nature and disease. Annual Reviews of Microbiology. 41: 435–464. Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. 1999. Bacterial biofilms: A common cause of persistent infections. Science. 284: 1318-22. Diaz F, Mosovich LL, Neter E. 1970. Serogroups of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the immune response of patients with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 121: 269-274. Diaz F, Neter E. 1970. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Serogroups and antibody response in patients with neoplastic diseases. American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 259: 340-345. Govan JRW, Deretic V. 1996. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiological Reviews. 60: 539–574. Hanlon WG, Denyer Ps, Olliff JC, Ibrahim JL. 2001. Reduction in exopolysaccharide viscosity as an aid to bacteriophage penetration through Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. American Society for Microbiology. 67: 2746-53. Harrison JJ, Turner RJ, Ceri H. 2005. Persister cells, the biofilm matrix and tolerance to metal cations in biofilm and planktonic Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biofilm Research Group. University of Calgary. 7: 981-94. Harrison JJ, Ceri H, Yerly J, Stremick CA, Hu Y, Martinuzzi R, Turner RJ. 2006. The use of microscopy and three-dimensional visualization to evaluate the structure of microbial biofilms cultivated in the Calgary biofilm device. Biological Procedures Online. 8:194-215. P a g e | 14 Herrmann G, Yang L, Wu H, Song Z, Wang H, Hoiby N, Ulrich M, Molin S, Riethmuller J, Doring G. 2010. Colistin-tobramycin combinations are superior to monotherapy concerning the killing of biofilm Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 202:1585-1592. Li Y, Zhang Q, Li J. 2010. Direct electrochemistry of hemoglobin immobilized in CuO nanowire bundles. Talanta. 83: 162-66. Lu X, Zou G, Li J. 2007. Hemoglobin entrapped within a layered spongy Co3O4 based nanocomposite featuring direct electron transfer and peroxidase activity. Journal of Materials Chemistry. 17: 1427-1432. Moskowitz SM, Chmiel JF, Sternen DL, Cheng E, Cutting, GR. Feb. 2008. CFTR-Related Disorders. [NCBI} National Center for Biotechnology Information. Accessed 2010 April 17 from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. [NCBI] National Center for Biotechnology Information. Moskowitz SM, Chmiel JF, Sternen DL, Cheng E, Cutting, GR. Feb. 2008. CFTR-Related Disorders. <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov>. Accessed 2010 April 17. Neter E. 1974. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection and humoral antibody response of patients with cystic fibrosis. The Journal of infectious diseases. 130: 132-133. Nickel JC, Ruseska I, Wright JB, Costerton JW. 1985. Tobramycin resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells growing as a biofilm on urinary catheter material. Journal of Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 27: 619624. Stewart PS. 1996. Theoretical aspects of antibiotic diffusion into microbial biofilms. Journal of Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 40: 2517-2522. Tirouvanziam.R, Gernez Y, Conrad KC, Moss BR, Schrijver I, Dunn EC, Davies AZ, Herzenberg AL, Herzenberg AL. 2007. Profound functional and signaling changes in viable inflammatory neutrophills. National Academy of Science. 105: 4335-4339. Walters CM, Roe F, Bugnicourt A, Franklin MJ, Stewart SP. 2003. Contributions of antibiotic penetration, oxygen limitation, and low metabolic activity to tolerance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms to ciprofloxacin and tobramyacin. American Society for Microbiology. 47: 317-23. Weinrauch Y, Drujan D, Shapiro SD, Weiss J, Zychlinsky A. 2002. Neutrophil elastase targets virulence factors of enterobacteria. Nature. 417: 91-94. P a g e | 15 Mark Ly Calgary, AB T1Y 3S2 Ly.Mark@gmail.com 403-285-6741 ∙ Cell 403-805-4844 Objective: Multidisciplinary researcher, Materials Chemistry and Infectious Disease Personal Skills Resourcefulness: Uses various avenues for learning new skills and ability to work independently or part of a team. Computer Skills: Proficient with MS Office applications, and basic troubleshooting Communication: Strong written and verbal communication skills demonstrated in reports and presentations within a multidisciplinary degree. Detail Orientated: Precise and orderly in analytical chemistry laboratory work. Education Bachelor of Science, Natural Science Concentration in Chemistry and Biology University of Calgary, Calgary AB, exp 2011 Relevant Courses Main group Chemistry o Synthesis of inorganic compounds and knowledge of inorganic solution chemistry Instrumental analysis o Experience analyzing inorganic materials using instrumental techniques Interfacial chemistry o Knowledge of surface films and interfaces involving metals. Functional Genomics o Introduced to high throughput methods and imaging techniques. P a g e | 16 FAHIMA NAKITENDE DEPARTMENT OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY fahmashadia@hotmail.com Objective: To be a Researcher in Nanomedicine HIGHLIGHTS OF QUALIFICATIONS AND SKILLS Undergraduate scientist, 1st concentration in Biology Research experience in nanoscience and nanomedicine in a Natural science project course, Science 501 Interest in learning and discovering new ideas in science Cooperative and team work skills Able to interpret and analyze data Sufficient knowledge about computers and mathematical skills Ability to communicate both written and orally Easily adaptable to various working environments Open minded , Voluntary and non judgmental Hard working and positive attitude EDUCATION B.S.c. Major Natural Science: 1st concentration in Biology, 2nd concentration in Math University of Calgary, 2007 VOLUNTEER AND EMPLOYMENT HISTORY May 2006-present Wal-Mart Health and Safety team associate, Calgary, AB 2009-present Volunteer one on one with Aphasia patients to help them improve on their speech (CHAT, Community Accessible Rehabilitation), South Calgary health centre, AB Volunteer in chat group among Aphasia patients, Community Accessible Rehabilitation, South Calgary Health Centre, AB 2006-present Voluntary member of SIMS (Students interested in medical school), University of Calgary 2006-present Voluntary performer and a member of ASA (African students association), University of Calgary P a g e | 17 SHANNON WESLEY 610 7th Street NW High River, AB T1V 2C8 (403) 652-1679 sbwesley@ucalgary.ca Objective: Nanoscience and Biofilm Researcher, Nanotechnology and Medicine QUALIFICATIONS Work experience in a 3-year research study about oil & gas emission effects on cattle 10 years of work experience in veterinary medicine, food safety, pathology, and disease Microbiology research experience as an Animal Health Technologist and scientist Comfortable training new employees, working in large groups, and peer mentoring EDUCATION Diploma in Animal Health Technology – Olds College, Olds AB, 2001 Bachelor of Natural Science – University of Calgary, Calgary AB, exp. 2012 RELEVANT SKILLS AND EXPERIENCE Research Experience Western Interprovincial Scientific Studies Association (WISSA) research study (2002-2005) - data entry using Microsoft Access databases - organ and tissue sample collection from aborted or stillborn calves University of Calgary Microbiology laboratory (2010) – microorganism growth and identification Communication and Leadership Experience Peer mentor for Dr. Lisa Bryce – COMS 363 Professional and Technical Communication (2011) - responding constructively to students’ ungraded oral and written assignments - advising, guiding, and conversing with students individually about course material - cyber mentoring (online communication with students) - facilitating class discussions Professional Involvement Alberta Association of Animal Health Technologists (AAAHT) – 10 year Active Service Award Arts Peer Mentorship Program (Winter 2011) – University of Calgary Biology Students’ Association – University of Calgary Chemistry Students’ Chapter – University of Calgary EMPLOYMENT HISTORY May 2005 – present June 2002 – May 2005 June 2001 – May 2005 Canadian Food Inspection Agency – EG03 Meat Hygiene Inspector Supervisor: Dr. Constance Taylor (403) 652-8413 University of Saskatchewan – Research Data Entry Clerk Supervisor: Dr. Richard Kennedy (403) 627-5481 Pincher Creek Veterinary Clinic – Animal Health Technologist Supervisor: Dr. Charles Zachar (403) 627-3900 REFERENCES AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST P a g e | 18 BUDGET Summer students: We plan on having 2 summer students for the first year at a rate of $5K/student each year with a total of $10K. We then plan on hiring 2 graduate students of $13k/student for the second year for a total of $26K. Over the 2 year period the gross total cost for personnel is expected to be $36K without considering USRA grants and TA positions. Publication costs: We plan on publishing a paper in the American Society for Microbiology. The cost associated with publishing this will be $3549. Equipment costs: We will need to purchase materials to create our own Pseudomonas Aeruginosa biofilms. The lab of Dr. Douglas Storey at the University of Calgary will provide the bacterial strain. 630 LB Agar plates ($2393.20) and 100 mg each of de-protonated tobramycin and de-protonanted ciprofloxacin (Total $198.90), will be purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. There will be a rental fee associated with the use of the X-Ray Diffraction microscope ($15/hour) in the department of Geology at the University of Calgary. Chemicals for creating the copper-oxide nanowire bundles will be provided by the Department of Chemistry at the University of Calgary. We will use the Nicolet Avatar FT-IR Mass spectrometer at the University of Calgary Chemical Instrumentation Facility. We will require a 3D Gyratory Rocker ($1114.99), an incubator ($2291.94), and a refrigerator ($150.00). Personnel: We plan to hire a lab technician to set up and maintain our equipment during the 2-year period costing $40K/year for a total cost of $80K. Traveling Costs: We expect to present our findings at the Alberta Nanotech showcase ($25/registration). We plan to send 2 people to the International Conference on Nanotechnology, which should be a total of ($3K). The total cost over 2 years will be $129 198.03. P a g e | 19 TIMELINE We expect to take 8 months to do our experimental process which consists of making, observing, and examining our copper-oxide nanowire bundles, biofilms, and our synthetic net. Testing of our hypothesis will also be done in this 8 month period. The next 4 months will be designated for data collection, and analysis of our results. The following year, we will spend 4-5 months interpreting our results. The remainder of our time will be spent writing our paper and attending conferences to promote our findings. Month 1-8 - Experimental procedure o Creating bioflims, CuO NWBs, synthetic NET o Collecting data Month 9-12 - Data collection and analysis Month 13-17 - Interpretation of results Months 18-24 - Writing paper Promoting findings