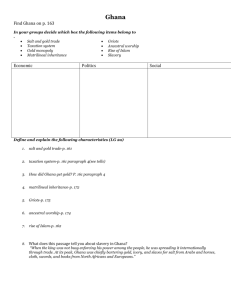

Tsikata and Seini 2004 "Identities, Inequalities & Conflicts in Ghana"

advertisement