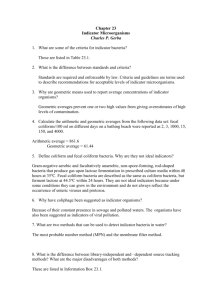

Coliform Bacteria an..

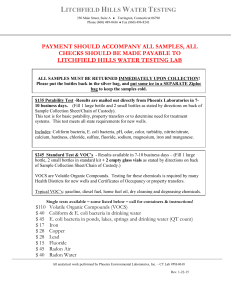

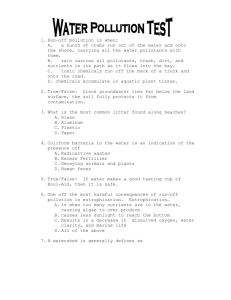

advertisement

INTRODUCTION Bacterial contamination cannot be detected by sight, smell or taste. The only way to know if a water supply contains bacteria is to have it tested. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) requires that all public water suppliers regularly test for coliform bacteria and deliver water that meets the EPA standards. Public water systems are required to deliver safe and reliable drinking water to their customers 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. If the water supply becomes contaminated, consumers can become seriously ill. Fortunately, public water systems take many steps to ensure that the public has safe, reliable drinking water. One of the most important steps is to regularly test the water for coliform bacteria. Pathogens are relatively scarce in water, making them difficult and time-consuming to monitor directly. Instead, fecal coliform levels are monitored, because of the correlation between fecal coliform counts and the probability of contracting a disease from the water. Coliform bacteria are organisms that are present in the environment and in the feces of all warmblooded animals and humans. Coliform bacteria will not likely cause illness. However, their presence in drinking water indicates that disease-causing organisms (pathogens) could be in the water system. Most pathogens that can contaminate water supplies come from the feces of humans or animals. Bacterial contamination cannot be detected by sight, smell or taste.Testing drinking water for all possible pathogens is complex, time-consuming, and expensive. It is relatively easy and inexpensive to test for coliform bacteria. If coliform bacteria are found in a water sample, water system operators work to find the source of contamination and restore safe drinking water. Fecal Coliform Fecal coliform bacteria are a group of bacteria that occur in large numbers in the gut and feces of humans and other mammals. They enter streams and lakes with sewage or wastes. Most fecal coliforms are normal inhabitants of the digestive tract and considered relatively harmless. In fact, their absence can lead to some types of vitamin deficiencies in humans. However, their detection in water may indicate the presence of more harmful microorganisms found in feces. E. coli is the major species of the fecal coliform group. TYPES OF TESTS There are different groups of coliform bacteria; each has a different level of risk. The name "coliform" is given to a whole group of bacteria which can occur in water and indicate potential health problems. They are divided into two groups: Total coliform (TC), which are all of the coliform bacteria, and fecal coliforms (FC), which are a portion of the TC. The FC group is considered much more serious from the hygiene viewpoint. Positive tests for the presence of TC, and more particularly FC, indicate serious hygiene safety issues in water. Total coliform, fecal coliform, and E. coli are all indicators of drinking water quality. Total coliform (TC) bacteria are commonly found in the environment (e.g., soil or vegetation) and are generally harmless. Total coliforms include a wider variety of bacteria including Escherichia coli and a broad spectrum of other bacteria. These other bacteria are able to grow frequently in the intestine, but can also grow to a variable extent in the environment. In consequence, the TC count does not necessarily relate specifically to fecal pollution, but to the bacterial loading of intestinal bacteria within a water system. Since the count is dominated by the bacteria which can occur in the intestine, it is used as a broader spectrum test for fecal pollution in a water system. Fecal coliforms (FC) are types of total coliform that mostly exist in feces. Fecal coliforms are pretty specialized types of bacteria and are dominated by Escherichia coli also known as E. coli. This bacterium thrives in the healthy human intestine and passes out in high numbers in the fecal material. What is important to remember is that the presence of FC is a widely accepted indicator of the potential pollution of water with fecal material. If that material is present, then there is a much greater risk of infectious microorganisms occurring in numbers large enough to cause an infection to break out if the water is consumed. These organisms include viruses, other bacteria, protozoa and a variety of worms. E. coli is a sub-group of fecal coliform. Escherichia coli are common in the human intestine, but it is not usually harmful. (However, there are some strains which can cause infections.) The presence of E. coli in a drinking water sample almost always indicates recent fecal contamination. E. coli outbreaks receive much media coverage. Most outbreaks have been caused by a specific strain of E. coli bacteria known as E. coli O157:H7. The maximum standard for coliform bacteria in drinking water is zero (or no) total coliform per 100 ml of water. If fecal coliform counts are high (over 200 colonies/100 ml of water sample), there is a greater chance that pathogenic organisms are also present. A person swimming in such waters has a greater chance of getting sick from swallowing disease-causing organisms, or from pathogens entering the body through cuts in the skin, the nose, mouth, or the ears. Diseases and illness such as typhoid fever, hepatitis, gastroenteritis, dysentery, and ear infections can be contracted in waters with high fecal coliform counts. Coliform standards of bacteria per 100 ml for various water uses are listed in the table below. Fecal and Total Coliform Standards for Water Coliform Standards (bacteria (colonies) / 100 ml Drinking Water Total body contact (Swimming) Partial body contact (Boating) 0 FC 200 FC 1000 FC 1 TC 2000 TC 10,000 TC TESTING PROCEDURES TOTAL COLIFORM AND FECAL COLIFORM TEST Plate Count Method In this exercise you will analyze different water samples for bacteria, and, in particular, an indicator group of bacteria called the coliforms. Although you will be looking at the total counts of bacteria in the water samples, the coliform bacteria are the critical test organisms which are found in improperly treated water or water that has fecal contamination. This test tends to indicate only the bacteria which grow rapidly at higher temperatures (30-40oC) in 48 hours. These bacteria are more likely to have originated from warm blooded animals (including humans) rather than from the environment where temperatures are commonly at less than 30 0C. In this test, the water is diluted and streaked across the surface of the agar. The agar is to too rich in nutrients for many of the environmental bacteria. All colonies are counted and weighted by the dilution factor to give the bacterial population per ml. Each colony is presumed to have been formed from one bacterial unit to form a colony forming unit which grows distinctly within or upon the agar. There is an indicator dye in the agar gel that colors the colonies. Confirmed coliforms are red and blue colonies. Confirmed E. coli coliforms are blue colonies. COLIFORM PLATE COUNT: The pH indicator violet red is incorporated into the gel, along with bile which inhibits gram positive bacteria. In addition, there is an indicator of the enzyme glucuronidase which will turn blue if the bacterium makes the enzyme. You may also see carbon dioxide gas bubbles between the film and the bottom of the petrifilm. Most E. coli make both the glucuronidase and CO2, and those colonies will be blue or blue-red. Non-fecal coliforms will be red colonies Procedure 1. Use an eyedropper to collect a 1 ml water sample and deposit the sample on to the surface of an agar plate. 2. Incubate the inoculated agar plate for 48 hours at 400C. 3. Count the red and the purple colonies in the agar plate as total coliforms and only the purple colonies as fecal coliforms. E.coli TEST E. coli has the rather unique ability to ferment the sugar lactose to produce acid and gas products. So if you find lactose-fermenting bacteria in something the chances are high that it is E. coli and that the material is contaminated with feces. Because of these characteristics E. coli was chosen as the indicator of fecal pollution of water. All bacteria are like bags of enzymes and they selectively use different foods, particularly sugars. One of the favorite sugars for the coliform group is lactose. Strangely, that is the main sugar in mother's milk and, therefore, the first one that the bacteria in the baby's intestine come across after the baby has been born and is suckling the milk. Bile is pretty lethal to bacteria, but the E.coli bacteria can tolerate it. Therefore, it was found that a soup rich in lactose and bile encouraged the E.coli to grow while discouraging competition (that cannot use lactose or tolerate the bile salts). Not only that, but the E.coli produce quantities of gas when feeding on the lactose. It is possible to use this gas presence to detect E.coli. For example, if you took 100 ml of water and found that gas was produced from 2 ml sample of water when the lactose bile broth was added, but none was produced from 1 ml, then that would suggest that the water contained 50 coliforms per 100 ml (ie. enough for just 1 cell in every 2 ml of water). Bacteria can make the water go cloudy (it can take as many as 100,000 to 10 million cells per milliliter to do this), taste peculiar, generate odd odors and the population can harbor some potentially dangerous organisms to human health. Traditionally, the coliform test has been used to determine whether there are any dangerous bacteria present, since the coliforms are thought to be a good indicator of fecal pollution. The test for presence of E. coli involves adding a portion of the water sample to lactose broth tubes which contain small inverted tubes for trapping any gas formed. Following a 24 hour at 37 oC incubation tubes that contain at least 10% gas in the inverted tubes are determined to test positive for E. coli. Procedure 1) Obtain lactose broth tubes and label them 2) Add the indicated amount of water sample to the labeled tubes, mix briefly. 3) Incubate at 37oC for only 24 hours. 4) At the next lab count the number of positive lactose fermenters Questions 1) Explain why E. coli was chosen as the indicator of fecal pollution? 2) Why does the dye in the Endo medium change color? 3) What is the major gas in the inverted tubes of the MPN test? On the left is a filtered sample. One the right is the nonfiltered sample which is cloudy and has a gas bubble in the inner tube indicating coliform bacteria were present in the unfiltered water. QUESTIONS: 1. What criteria are used to define the coliform group? 2. Why is there a dye added to the coliform petrifilms? 3. Why are coliforms used as indicator organisms for water impurity?