Paragraph Writing Handbook for Instructors

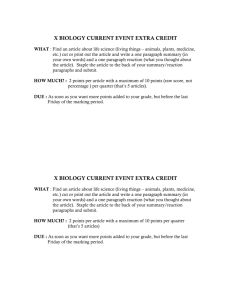

advertisement

PARAGRAPH WRITING A Guide to Writeousness for Instructors Handbook prepared by Lyon Rathbun, Mark Blakemore, Eileen Michal, and Richard Price; Spring 2011 1 Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3 II. THE PROMPT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5 III. THE RUBRIC . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6 IV. GOOD PARAGRAPHS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7 V. GOOD SENTENCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9 APPENDIX A. EXAMPLES OF PROMPTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16 APPENDIX B. EXAMPLES OF RUBRICS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .18 2 I. INTRODUCTION PARAGRAPH WRITING: WHY? If we want to serve our students well we could not do better than to see to it that they graduate with the ability to write clearly and professionally. The lack of this ability is a long-standing complaint of employers, graduate schools and professional schools. If we can produce competent writers we will be sending our graduates forward with a big advantage. But there is another reason to focus on writing. The kind of writing that is described here is an important, perhaps necessary part of the development of critical thinking. The typical college writing experience, what UTB has offered in the past, is two courses explicitly for writing and courses (literature, history, ...) that feature essay writing. The writing proficiency of graduates, at UTB and elsewhere, shows that this doesn't work. There would seem to be two reasons for this. First, writing is still a now and then thing in the curriculum of most students. Second, the emphasis is on several-page essays, undertakings too vast for students to learn the fundamentals of constructing and clearly conveying an argument; they are assigned a cross country trek before they can walk across the room. There is a solution. We need to develop the practice of paragraph writing in almost every course, writing in which the students present an argument for an answer to a courserelated question. There are many advantages to this method: A paragraph is applicable to any course. We have instructors who use it in English in Math, in Business, in Engineering ... A paragraph is short. A student can see logical flow and flaws in a way that is difficult in an essay. Paragraph grading does not burden the instructor's time or tolerance the way essay grading does. If paragraph writing is a feature of all courses, instructors will not have to teach it anew in every course, nor convince students anew that it is worthwhile. If students learn to write effective paragraphs they will have mastered the blocks from which they can construct effective essays. Instructors in essay-heavy courses have learned to appreciate the power of paragraph writing. A faculty development program on paragraph writing, leading to a certificate, started in the spring of 2010. The program, each semester, consisted of four workshops directed towards a capstone project in which the participants implemented a paragraph writing exercise in a course being taught. There was an overwhelmingly positive response by the participants (and by many students!). There were several converts, participants who were 3 skeptical at the beginning but who, after the capstone experience, had a eureka moment, "This works!" One kind of evidence that this works has been mentioned by instructors using paragraph writing: student progress in mastering curricular material may be disappointing, but the improvement in student writing and critical thinking is heartening. Because universality and some measure of uniformity are important to the future of paragraph writing, at UTB we encourage the use of a distinctive “markup language” for indicating errors in writing. The abbreviations used in this system are given below, and are all in ASCII, so they can be used for grading online as well as with the traditional red pen. PARAGRAPH WRITING - HOW? There are only four concepts to know in this Handbook of Paragraph Writing: Know that paragraph writing is different from essay writing. Give a good "prompt." Use an appropriate "rubric." Grade the way you said you would grade. Paragraph writing is different The crucial difference must be understood between the essay writing used in KBachelor's education and paragraph writing. In essay writing organization is a major task, and many logistical skills (references, citation style ...) are to be learned. Paragraph writing is focused on a narrow issue and has a clear target. For students to understand what that target is, they must be given a good "prompt." The prompt The prompt is the writing assignment. It is more-or-less the question that the student is supposed to answer, or the goal that is to be reached in the paragraph. It includes the expectations and restrictions on the assignment. During the paragraph writing workshop program, those instances in which the capstone paragraph writing implementation was less successful could be traced in every case to a prompt that was not carefully crafted. For an experienced user of paragraph writing, this craft can become an art. Indeed, the art of implementing paragraph writing is the art of giving a great prompt. Rules, tips and examples of prompts are given below in this document. The rubric The rubric is the set of rules that govern how you will grade the paragraph writing assignment. Rubrics should reflect the nature of the course, and the style of the instructor. The rubric for a history course may not be appropriate for an engineering course; the rubric for Prof. Yin might be uncomfortable for Prof. Yang. 4 A further discussion and examples are given below in this document. Grading as promised A student's paragraph will display knowledge of the course material and writing effectiveness. You may have to give credit to a well written and reasoned paragraph that displays complete ignorance of the course content; you may have to give a low grade to the only student who gives a technically correct answer, if that answer is poorly presented. If we want students to write more effectively, they must believe that it truly is closely coupled to their grade. II. THE PROMPT The prompt is the statement/question that sets down the student task. A good prompt can yield some bad student writing; a bad prompt will preclude good writing. Examples of prompts are given in Appendix A. Some of those are prompts that have been used in capstone projects. The following general tips are based on experience with paragraph writing. It must be made absolutely clear to students that they are to write a paragraph, not an essay. It is to be a single paragraph that stands alone. You may want to suggest an appropriate range for the number of lines or words. You may want to include in your grading rubric a severe penalty for multiple paragraphs. No matter how strongly you shout the messages “paragraph,” “explain,” and so forth, some students will sleep through your shouts – at least the first time paragraph writing is assigned. They will be alert to the messages the second time only if they are graded harshly for the missed message on the first assignment. Be sure that your instructions are clear enough, and repeated often enough that you will have an easy conscience when you give a low grade for writing that is not responsive to the instructions. A good prompt specifies a very narrowly defined topic. Compare the following: o o o o Bad: Summarize chapters 5 through 12 of the Jones' textbook Good: What was the single most important lesson in today's reading? Bad: Review and contrast English common law and Napoleonic law. Good: Explain the different roles of “precedent” in English common law and the Napoleonic code. An optimal prompt should encourage critical thinking by requiring that the student supply an argument leading to the answer. One way of accomplishing this is to ask the student to distinguish the heart of a matter from its peripheral details. o Bad: Give the history of plastics with an emphasis on the advantages of plastics over other materials in various applications. o Good: How would you decide whether a new material should be called a “plastic”? o Bad: List the continents in decreasing order of size. 5 o Good: Why is Australia considered a continent, not an island? The best prompts require that a student show mastery of general principles by giving the answer to a very specific paragraph-appropriate question. o Bad: Give the mathematical basis for amortizing mortgages. o Good: If the interest rate on a 30 year mortgage doubles, explain why the total amount of interest paid in 30 years does not double? Beware of certain essay-appropriate words and phrases that generally are not appropriate for paragraph writing prompts: “list,” “include,” “give at least five examples of ...” A lengthy prompt is generally not a good idea. It sets the wrong tone for eliciting a short, written response. III. THE RUBRIC You must let students know on what basis they will be graded. This basis consists of general rules (“Only one paragraph!”) and a specific weighting of points for different aspects of the paragraph assignment, the rubric itself. General rules The following are good rules in most cases. Instructors will want to add what is appropriate to their course or their taste. Students should not repeat the prompt as part of their paragraph. The student is to write as if the reader already knows what issue is being addressed. Paragraphs should have little or no repetition of any kind. One corollary of this is that stand alone paragraphs generally should not have “conclusions” or “summaries.” Students are typically taught that a paragraph should have a topic sentence. This may be appropriate for a paragraph that is embedded, along with many other paragraphs, in a long document. It has no purpose in a stand-alone paragraph for which the prompt serves the purpose of a topic sentence. Again, the student is to write as if the reader already knows what issue is being addressed. There should be no “displayed” material (mathematics or graphs set apart from the text). Mathematical expressions can be used if they are in the text itself, as in “The expression x2 has the value of x multiplied by itself.” o A paragraph should not contain more than 300 (or whatever) words. o The paragraph should not contain lengthy quotations, quotations of more than a few words. 6 o Unlike an essay assignment, a paragraph assignment generally is not meant to have references. The grading menu What is usually meant by “rubric” is a list of points associated with the various aspects of writing. A professor who has used paragraph writing for many years in physics homework and exams has a minimalist rubric: 60% for technical content (did the student get the right answer to the physics question?), and 40% for the clarity of the writing. That 40% covers spelling, grammar, logical flow, etc., but all those elements contribute to the overall clarity of the paragraph, and the 40% judgment is made of the overall clarity. Other instructors find it useful to give a complete breakdown of how many points are assigned for each element of the answer. Several examples of such rubrics can be found in Appendix B. The advantage of such a fine-tooth grading comb is that it removes some of the subjective element from a process that is necessarily somewhat subjective. Also, it helps to avoid student complaints, and – at least in principle – helps students to recognize their weak points. It does, of course, make grading paragraphs more tedious. IV. GOOD PARAGRAPHS When you use paragraph writing, you will want to be certain that you yourself can write good paragraphs, and that you can give advice to students on how to write good paragraphs. Fortunately, and surprisingly, there is a straightforward algorithm for writing clear flowing paragraphs. (These paragraphs must contain good sentences, of course, but sentences have a much more complicated life that will be skimmed in the next section.) The paragraph algorithm comes from cognitive studies, and examinations of the way in which professionals write badly. Here is the magic formula in its theoretical form: the arrangement of the words must convey the flow of the argument being constructed. Here is the magic rule, the “known to new” rule, in its applied form: the beginning of every sentence should link back to previously developed words and ideas; the end of the sentence should introduce new material. As usual, an example will make this clearer. This is an example of a particularly plausible prompt in an introductory physics course. Prompt In physics we learn that energy is conserved. Yet we are frequently reminded that we must conserve energy. In a single clear, coherent paragraph resolve this paradox. Response in a bad paragraph Heat and the random motion of air are not useful. The total amount of energy in the world cannot be increased or decreased according to physics. Gasoline has a useful form of energy called chemical energy. Politicians tell us frequently to conserve energy. Of 7 course, the total energy includes forms of energy such as chemical, electrical, nuclear, thermal and so forth. When we drive we use the chemical energy of gasoline. Physics courses use words precisely, but words are used imprecisely in everyday speech. Our driving results in the generation of lots of heat and air motion. Response in a good paragraph Words are used with precise meaning in science. The word "energy," when used in a physics course, is an example: it means the total amount of all forms of energy, including electrical, chemical, heat energy and so forth. This total cannot be increased or decreased; the universe has a fixed amount of it. The word "energy," however, can have a different meaning when used in newspapers and by politicians; it means energy that is available to do useful work. As we drive our 8,000 lb SUV to school, we are converting the useful chemical energy of gasoline into useless hot exhaust and moving air. Nature conserves all of energy. We must conserve useful energy. There are many lessons in this one six-sentence example. Notice that the first response paragraph has no grammatical or syntactical mistakes, and it contains all the right principles, yet it is nearly impossible to figure out what point it is making. But the point made by the second response paragraph is completely clear. Now, go back and read the first response paragraph again. On this second reading it too is clear. Once you know what point is being made, you can understand how each sentence in that first response supports the point. What features in the second paragraph let us know so clearly where it is “going”? Look at the second sentence; right at the start we have “word” which links back to the first sentence. Ah ha! The answer is going to have something to do with the usage of words. The second sentence adds new material about words, and the way in which the word energy is used and in particular on the importance of “total.” The following sentence, the third, starts with “This total ...” and introduces new information about it. The beginning of the fourth sentence has “word” and “energy” and links back to the previous sentences. This sentence also introduces the crux of the argument: a difference between the scientific and popular usage of the word “energy.” The scene now has been set and the fifth sentence indulges in some playfulness. The sixth sentence drives the principal point home. (In some sense it is a “conclusion,” but it is not explicitly labeled as such, and it fits remarkably well into the flow of the paragraph.) By adhering to “known to new,” clarity of this second response is assured. Start with a link to what precedes; move to the new information. We always know just where the argument is going, just what story we are being told. A detailed discussion of this, and some secondary rules for clear flow in writing can be found in the article “The Science of Scientific Writing,” by Gopen and Swan, whose philosophy is summarized in their statement: “If the reader is to grasp what the writer means, the writer must understand what the reader needs.” The article first appeared in the American Scientist (Nov-Dec 1990), Volume 78, 550-558, and is available online at: http://www-stat.wharton.upenn.edu/~buja/sci.html 8 In the UTB writing markup system two paragraph-related errors deserve special notations. In our introduction of that markup system, the name of the error comes first, followed by the abbreviation set off with square brackets [ ] to be used in grading. For the paragraph-related errors that are our first instances of this, the names and bracketed abbreviations are the same. Flow [FLOW] A flow error means it is difficult or impossible to infer what point is being made by the paragraph. This error can usually be fixed by the “known to new” rule. The second paragraph-related error is: Garbled [GARBLED] A sentence or paragraph is marked “garbled” if its meaning can hardly be grasped. This mark on a paper lets the writer know that small changes will not produce acceptable text; the writer should probably start over. V. GOOD SENTENCES Unlike paragraphs, sentences can fail in many independent ways. Here we list some of the worst and some of the most common errors, along with their names and abbreviations in the UTB markup language. More detailed (much more detailed) lists, discussions and exercises can be found at Sentence Structure – Purdue University Online Writing Lab. Retrieved from http://owl.english.purdue.edu/exercises/5/. We have liberally drawn from the work of Stanford University’s Andrea Lunsford in her fourth edition of The Everyday Writer. Retrieved from http://bcs.bedfordstmartins.com/everyday_writer/20errors/1.html et seq. Completely wrong word [WW1] The word used has a meaning very different from what the writer meant; the use of the word creates writing that is meaningless, comical, or – at best – different from the writer's intent. RUN-ON SENTENCE [RO] A run-on sentence is created when clauses that could each stand alone as a sentence are joined with no punctuation or words to link them. Run-on sentences must either be divided into separate sentences or joined by adding words or punctuation. SENTENCE FRAGMENT [FRAG] A sentence fragment is part of a sentence that is written as if it were a whole sentence, with a capital letter at the beginning and a period, question mark, or an exclamation point at the end. A fragment may lack a subject, a complete verb, or both; a fragment may depend for its meaning on the sentence before it. A writer can check for sentence fragments by reading a draft out loud, backwards, sentence by sentence. Out of normal order, sentence fragments stand out clearly. COMMA SPLICE [CS] Comma Splices occur when only a comma separates clauses that could each stand alone as a sentence. To correct a comma splice, a writer can insert a semicolon or period, add a word like and or although after the comma, or restructure the sentence. 9 WRONG TENSE OR VERB FORM [VERB T] Errors of wrong tense or wrong verb form include using a verb that does not indicate clearly when an action or condition is, was, or will be completed — for example, using walked instead of had walked, or will go instead of will have gone. Some varieties of English use the verbs be and have in ways that differ significantly from their use in standard academic or professional English. Errors may occur when a writer confuses the forms of irregular verbs (like begin, began, begun or break, broke, broken) or treats these verbs as if they follow the regular pattern — for example, using beginned instead of began, or have broke instead of have broken. LACK OF SUBJECT-VERB AGREEMENT [AGR S/V] A verb must agree with its subject in number and person. In many cases, the verb must take a form depending on whether the subject is singular or plural: The old man is angry and stamps into the house, but The old men are angry and stamp into the house. Lack of subject-verb agreement is often just a matter of leaving the -s ending off the verb out of carelessness, or of using a form of English that does not have this ending. Sometimes, however, this error results from sentence constructions. A writer can check a draft for subject-verb agreement problems by circling each sentence's subject and drawing a line with an arrow to that subject's verb. LACK OF PRONOUN- ANTECEDENT AGREEMENT [AGR P/A] Pronouns must agree with their antecedents in gender (for example, using he or him to replace Abraham Lincoln and she or her to replace Queen Elizabeth) and in number (for example, using it to replace a book, and they or them to replace fifteen books). MISPLACED MODIFIER [M/MOD] Readers are sometimes amused, but always confused, when they encounter sentences such as “They could see the eagles swooping and diving with binoculars.” Who was wearing the binoculars – the eagles? The sentence comes into clear focus when the modifier is placed close to the word it describes: “With binoculars, they could see the eagles swooping and diving.” DANGLING MODIFIERS [D/MOD] A close cousin of the misplaced modifier, the dangling modifier hangs precariously from the beginning or end of a sentence, attached to no other word in the sentence. The word that the phrase modifies may exist in the writer's mind but not on paper. Consider the following: “A doctor should check your eyes for glaucoma every year if over fifty.” Who is at risk for glaucoma – the doctor, or patient? The modifier (“if over fifty”) needs to describe a specific person in the sentence: “A doctor should check your eyes for glaucoma every year if you are over fifty.” INEFFECTIVE WORD [WW2] While a “wrong word” [WW1] utterly misrepresents the author’s intended meaning, an ineffective word suggests what the writer meant, but still misses the mark by suggesting a connotation that the writer did not intend. 10 Below are examples for you to use: The sentences marked by “*” indicate flawed sentences. RUN-ON SENTENCE [RO] Example *The current was swift he could not swim. The current was swift. He could not swim. The current was swift; he could not swim. The current was swift, and he could not swim. SENTENCE FRAGMENT [FRAG] NO SUBJECT Example *Marie Antoinette spent huge sums of money on herself and her favorites. Helped bring on the French Revolution. Marie Antoinette spent huge sums of money on herself and her favorites. Her extravagance helped bring on the French Revolution. INCOMPLETE VERB Example *The old aluminum boat sitting on its trailer. The old aluminum boat was sitting on its trailer. (Sitting cannot function alone as the verb of the sentence. Adding the auxiliary verb was turns it into a complete verb, was sitting, indicating continuing action.) BEGINNING WITH A SUBORDINATING WORD Example *We returned to the drugstore. Where we waited for our parents. We returned to the drugstore, where we waited for our parents. 11 COMMA SPLICE [CS] Example *Westward migration had passed Wyoming by, even the discovery of gold in nearby Montana failed to attract settlers. Westward migration had passed Wyoming by; even the discovery of gold in nearby Montana failed to attract settlers. WRONG TENSE OR VERB FORM [VERB T] Example *By the time Ian arrived, Jill died. By the time Ian arrived, Jill had died. (The verb died does not clearly indicate that the death had occurred before Ian arrived.) *The Greeks builded a wooden horse that the Trojans taked into the City. The Greeks built a wooden horse that the Trojans took into the city. (The verbs build and take have irregular past-tense forms.) LACK OF SUBJECT-VERB AGREEMENT [AGR S/V] Example 1 *A central part of my life goals have been to go to law school. A central part of my life goals has been to go to law school. (The subject is the singular noun part, not goals.) Example 2 *The two main goals of my life is to be generous and to have no regrets. The two main goals of my life are to be generous and to have no regrets. (Here, the subject is the plural noun goals, not life.) 12 Example 3 *The senator and her husband commutes every day. The senator and her husband commute every day. (If a subject has two or more parts connected by and, the subject is almost always plural.) Example 4 *My brothers or my sister comes every day to see Dad. My brothers or my sister come every day to see Dad. (If a subject has two or more parts joined by or or nor, the verb should agree with the part nearest to the verb. Here, the noun closest to the verb is a singular noun. If this construction sounds awkward, consider the next edit.) Example 5 *My brothers or my sister commute every day from Louisville. My sister or my brothers commute every day from Louisville. (Now the noun closest to the verb is a plural noun, and the verb agrees with it.) Example 6 *Each of these designs coordinate with the others. Each of these designs coordinates with the others. (Most indefinite pronouns such as each, either, neither or one are always singular and take a singular verb.) Example 7 *Many of these designs coordinates with the others. Many of these designs coordinate with the others. (The indefinite pronouns both, few, many, others and several are always plural and take plural verb forms. Several indefinite pronouns (all, any, enough, more, most, none, and some) can be singular or plural depending on the context in which they are used.) 13 • LACK OF PRONOUN- ANTECEDENT AGREEMENT [AGR P/A] Some pronoun problems occur with such words as each, either, neither, and one, which are singular and take singular pronouns: Example 1 *Each of the puppies thrived in their new home. Each of the puppies thrived in its new home. Problems can also occur with antecedents that are joined by or or nor: Example 2 *Neither Jane nor Susan felt that they had been treated fairly. Neither Jane nor Susan felt that she had been treated fairly. Some problems involve words like audience and team, which can be either singular or plural depending on whether they are considered a single unit or multiple individuals: Example 3 *The team frequently changed its positions to get varied experience. The team frequently changed their positions to get varied experience. (Because team refers to the multiple members of the team rather than to the team as a single unit, its needs to be changed to their.) Another antecedent that causes problems is an antecedent such as each or employee, which can refer to either man or woman. Use he or she, him or her, and so on, or rewrite the sentence to make the antecedent and pronoun plural or to eliminate the pronoun altogether: Example 1 *Every student must provide his own uniform. Every student must provide his or her own uniform. Example 2 *Every student must provide his own uniform. All students must provide their own uniforms. 14 Example 3 *Every student must provide his own uniform. Every student must provide a uniform. MISPLACED MODIFIER [M/MOD] Example *He had decided he wanted to be a doctor when he was ten years old. When he was ten years old, he had decided he wanted to be a doctor. (What kind of a doctor could he be at age ten?) DANGLING MODIFIERS [D/MOD] Example *Opening the window to let out a huge bumblebee, the car accidentally swerved into an oncoming car. When the driver opened the window to let out a huge bumblebee, the car accidentally swerved into an oncoming car. INEFFECTIVE WORD [WW2] Example *The model was skinny and fashionable. The model was slender and fashionable. (The connotation of the word skinny is too negative.) 15 APPENDIX A EXAMPLES OF PROMPTS The following are examples of prompts for UTB courses, many of them actually used in assignments. In a course in Ancient History: In one paragraph, explain what is revealed about Greek religion by the fact that Hera, Zeus’s wife, feels no hesitation throughout the Iliad in challenging, criticizing, and defying her husband, whose power is supreme among the Gods. In a course in Criminal Justice or Government: Describe in one paragraph the legal principle used by government agencies to justify the seizure of private property implicated in illegal drug activity. In a course in Business Law: “When does an idealistic business school graduate become a white-collar criminal? What causes a manger to jaywalk through the legal crossroad with criminal behavior? One's ethical standards should not change between personal and business activities. It is the ethical dealings and circumstances that are more complex in the business situation. Discuss the factors that influence managerial ethics leading from ethical/legal behavior to violation of criminal law. Do not discuss personal greed as a factor. In a course in Art History: In one paragraph, explain how Botticelli’s Primavera is a story of both ethos and pathos. In a course in Physics: “An absent minded student is walking up a down escalator at just the right rate so that the student does not advance upward or downward. Is the student doing physical work (work as defined in physics)? If the answer is 'yes,' explain how that can be consistent with the conservation of energy. Where does the energy go that is expended by the student?” 16 In a course in Nursing: An ethical dilemma stems from some nursing students who cheat on examinations. This implies an absence of virtue, and some may feel those individuals cannot be trusted to be honest about the care they give to patients. They may endanger patients by lying to protect themselves concerning errors of commission or omission of treatment. Should dishonest nursing students be denied a license to practice nursing? Write a one-paragraph response to this ethical dilemma and defend your answer. In a course in American History: In one paragraph, explain one key preconception of Manifest Destiny, the ideology used to justify the seizure of Mexican territory during the Mexican American War. In a course in Applied Health: “Describe the transmission, infection, and incidence of RSV (Respiratory Syncytial Virus), and its significance in premature infants and young children. In a course in Criminal Justice “In one effective paragraph explain what Uniform Crime Reports (UCR) are and briefly discuss their utility for criminal justice practitioners and scholars.” 17 APPENDIX B EXAMPLES OF RUBRICS The following are rubrics (grading schemes) that have been used for paragraph writing at UTB. Minimalist rubric used in technical courses: In this approach a physics instructor assigned 60% of the points for technical correctness of the answer, and 40% for clarity of the writing. The “clarity” was judged as a combination of grammar, syntax, word choice and flow. The judgment was made (somewhat subjectively) by the criterion of how easy it was to read the answer and understand what the student was thinking, whether that thinking was right or wrong. Sometimes the writing is such a barrier that it is impossible to determine whether the answer is technically correct. In this case it is essential to assume that the answer is wrong, so that we do not encourage students to write unreadable paragraphs in the belief they will be given the benefit of the doubt on the technical points. An applied technology instructor used a similar approach with 70% for technical correctness and 30% for writing, along with the following guidance to students: A plausible engineering solution presented in a logical manner will fetch a maximum of 70% of the grade Coherent and elegant presentation of the assumptions and solution to the design problem with logically constructed sentences will fetch the maximum of the remaining 30% of the grade 18 Example 1: A mediumalist rubric used in a Biology course This approach uses a 70/30 split for technical correctness/writing. The students are told that 70% of the grade is associated with the first two rows in the menu below, and 30% with rows three and four. They are given qualitative indicators of the criteria that are used, without a specific breakdown of points. Unacceptable Acceptable Good Exemplary 1. Accurate use of terminology Completely incorrect use of terminology. No idea what these words mean. Incorrect use of some terms. Vague understanding of terms. One or two incorrect usages. Fairly clear understanding of terminology. No errors in usage. Seems to clearly understand what is being said. 2. Recognition and interpretation of subject matter No identification of subject matter. Identification is inaccurate. It is evident in the writing that the student just does not get it. Some indications of subject matter are evident. A few errors in the interpretation of subject matter. Writing demonstrates unclear interpretation of subject matter. Less than complete focus on subject matter. One or two errors in interpretation. Pretty much understands the material, but not totally. Writing demonstrates complete focus on subject matter. Understands the material. No errors in interpretation. 3. Clarity of writing Garbled, run-on or incomplete sentences. Unrecognizable vocabulary. Poor cohesion; consistent flaws and lack of clarity in meaning. Few flaws and occasional lapses of cohesion and/or clarity without significant damage to the delivery of the meaning. Cohesive, clear, concise, free of mechanical and syntactical flaws; effective use of introduction and concluding sentences. 4. Format More than one One mistake in mistake including: format. handwritten, single-spaced, other than specified font and/or font size. One long quote. One mistake in format. Overuse of quotations. No mistakes in format. Typed, double-spaced, 12 point font and either Times New Roman or Courier New font. Proper use of quotations and citations. 19 Example: A maximalist rubric used in a Criminal Justice course: The following is an example of a rubric in which there is a separation of content and style into three different categories. The total number of points for the paragraph is 12; each of the categories has a maximum of four points which are awarded according to the following menu. Category 3 Good 2 Adequate Identification Factually accurate identification of required material. Material is defined accurately, but some required information is missing. Material is defined accurately, but responses given are not as strong as in the “good” category. Most Missing all required required information information. is missing & information is factually inaccurate. Explanations addressing the required material are insightful & demonstrate a clear understandin g of the material. Explanations demonstrate understanding of the required material, but responses given are not as strong as those in the “excellent” category. Explanations demonstrate only a surface understanding of the required material; responses have no real depth or insight. Explanations given are poorly thought out & lack clear comprehensi on of the material. No explanations of required material are given. Writing Style Clear, concise writing that flows well & is free from mechanical errors. Writing that flows well, but shows evidence of some mechanical errors. Writing that flows fairly well, but has several mechanical errors that distract the reader. The writing shows lack of clarity & flow, & has frequent errors that distract the reader. The writing is “garbled;” there is no flow or cohesion, & there are multiple errors. Significance 4 Excellent 20 1 Poor 0 Inadequate