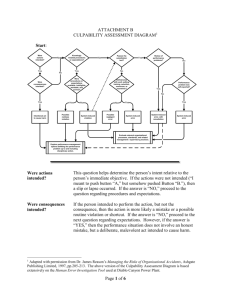

Unsafe Acts Algorithm more…

advertisement

Unsafe Acts Algorithm more… Psychologist James Reason constructed this algorithm to help front-line managers determine the culpability or blameworthiness of a single person involved in an incident. The algorithm should be applied to each individual act that contributed to an incident or near-miss. The key questions across the top of the algorithm determine the intent of the individual. Question 1: Were the actions as intended? If both the actions and the consequences were as intended, then the action is criminal and requires legal action beyond the organization. If the actions or consequences were not as intended, then consider the next question. Question 2: Evidence of substance use or illness? If the substance was taken for a known medical condition such as an antibiotic or antidepressant, the individual is less culpable than if an illegal substance was ingested. For the former, it must be acceptable in your culture for employees taking legally prescribed medications that affect cognition to not perform work that requires mental acuity and alertness. If substance use or abuse is not present, then consider the next question. Question 3: Knowingly violated safe procedures? If the violation was an automatic action such as a routine short-cut because there is not enough time to follow the safe procedure, then the violation is system-induced. Even if there was a conscious decision to break or bend a rule, it is most likely that the bad consequences of that decision were not intended. Consequently, the degree to which this decision is blameworthy is dependent upon the availability and effectiveness of the relevant policies and procedures. There are “necessary violations,” which are non-compliant but needed to get a specific task accomplished. When a nurse has tried five times to scan a drug in a bar code administration system, she/he may revert to manually reviewing the drug against the 7 rights of medication administration (give the right drug, to the right patient, at the right time, in the right dose, by the right route, for the right reason, and document it in the right way). The nurse was non-compliant because she/he did not scan the drug, but the procedure was not workable. In contrast, as Reason indicates, “when good procedures were readily accessible but deliberately violated, the question must arise as to whether the behavior was reckless.” Reckless behavior warrants disciplinary action. If the situation doe not involve deliberate non-compliance with an effective procedure that is in routine use, it is helpful to follow the dotted line and consider the substitution test. Question 4: Have other individuals who are equally competent made similar errors under similar circumstances? If the answer is ‘yes,’ then the error is blameless and system-induced. If the answer is ‘no,’ then consider whether there were system-induced deficiencies in the individual’s training, selection for the job, or experience. Bad work habits due to poor training and selection for the job are latent system sources of error. However, if there aren’t any such deficiencies, then it is likely that the error is due to negligent behavior. If equally competent individuals have made similar errors, consider the final question. Question 5: Does this individual have a history of committing unsafe acts? By this point, it is clear that the individual is largely blameless for this particular error. However, the question remains as to how often this person is absent-minded and prone to slips. At times it is appropriate for individuals who are less detail-oriented to be counseled regarding their appropriateness for a particular job within an organization. In summary, when bad consequences were the intent or substance abuse was involved, disciplinary and most likely legal consequences are necessary. Remember that front line workers usually know perfectly well who the habitual rule-breakers are. The departure and disciplining of an individual who habitually engages in negligent and/or reckless behavior makes the environment safer and encourages the perception of a just organizational culture. When authorized substances are used and workable procedures are violated, there is a gray area of culpability involving potentially negligent behavior that requires careful judgment. Finally, once the substitution test is passed, the event is blameless and a system improvement should be sought. Approximately 90% of unsafe acts are in this system-induced and blameless category. Source: Reason J. Engineering a safety culture. In ‘Managing the risks of organizational accidents.’ Aldershot, England, Ashgate Publishing Limited, pp. 208 – 211; 1997.