Entities

advertisement

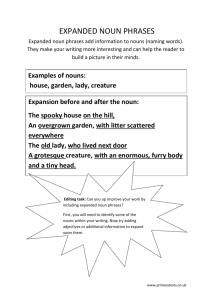

Entities 3.1. Introduction In this chapter, we consider the kinds of semantic properties that are typically encoded as noun. We begin with a survey of definition of noun as a syntactic, semantic, and discourse category and observe that, universally, temporally stable phenomena, entities, surface as nouns. We then look at the nature and encoding of eight kinds of semantic properties of noun/ entities: specificity, boundedness, animacy, kinship, social status, physical structure, and function. For each, we look at a number of subleases (e.g., humans, animals, and inanimate under gauges. Thereafter, we consider the theoretical problem of unifying the semantic properties of entities internally (in relation to each other via neutralization) and externally (in relation to perceptual and cognitive structure). 3.11. Nouns and entities: formal and notional definitions Any student reared in the western grammatical tradition will say that a nouns is the name of a person, place or thing and thus define a noun by its semantic representation. Two observations conspire to weed this view out of our untutored celiefs about language. First, there are many things that are nouns but not exactly person, places, or things. Smoothness is a noun, but it does not readily appear to represent a thing. Second , a noun is not a notional class, something defined by its conceptual content, out a from class, something defined by its structural or formal properties (Lyons 1966, 1968). Formally a noun is identifiable because of what other categories and form co-occur with it. Under this view, a noun is something that takes certain modifiers, like a definite article. By this criteria, smoothness is a noun, in spite of the variation in its national content, because it co-occurs with the definite article: the smoothness of the wood. The applicability of purely formal criteria for the identification of nouns is undeniable, even in languages where “nounhood” has to be more particularly defined: Russian and Chinese have no definite articles. For example, so the formal criteria have to be more carefully applied. But curiously, when the traditional notional definition (“a noun is the name of a person, place, or thing”) is reversed, the definition turns out to be true. Nouns are not always persons, places, or things, but persons, places, and things always turn out to be nouns! (see the work by Givon 1979, 1984; Haiman 1985a, 1985b; langacker 1987a, 1987b; Wierzbicka 1985). Nouns do have purely formal properties because at the grammatical level they are contenlessly manipulated by syntax, just like any other category, but these formal properties are supported by overwhelmingly consistent semantic factors. Nouns incontrovertibly tend to encode entities, broadly construed. This convergence of semantics and syntax is not meant to be reductionistic: syntax cannot be read directly off semantic no more than semantics can be read directly off culture. To say that from classes are semantically motivated is to agree that the best semantic account is one that respects a close connection between from and meaning rather that one that severely separates-modularizes-the two. This is a position more in line with Jackendoff’s Grammatical Constraint (see chap. 1), especially so beaus many morphosyntactic reflexes of nouns, such as number and gender, are correlated with, if not accountable to, the direct effect on the structural aspects of language, in this case categoriality, the status of from classes. The tradition national definition of noun thus resurfaces, if in modified from. 3.12. Three account of categories and their denotations A number of recent studies of the universality of grammatical categories have come to conclusions similar to those on the semantic motivation of nouns as a formal category. Our brief examination of three accounts-one from discourse and two from conceptual linguistic-will show us the consistencies in semantic representations that underlie nouns as a category. 3.121. Category in discourse Hopper and Thomson (1984, 1985) have observed that the major lexical categories of noun and verb have a consistent discourse definition: Nominal an verbal categoriality is a matter of degree and kind of information in discourse. The goal of discourse is to report events happening to participants, with verbs encoding the events and nouns the participants. From classes are direct result of the informational requirements of verbal reports: the more individuated or discrete a discourse event, the more likely it is to be coded as a full verb; the more individuated the disvourse participant, the more likely the form encoding the participant is to be a full noun. With regard to nouns in particular, Hopper and Thompson (1984, 1986) show that languages have syntactic operations to decrease the categorial status of a noun as a function of the individuation and relative salience of the discourse participant that the noun encodes. Some verb in English, for example, allow their semantically predictable direct object to incorporate, or fase, with a verb to from a new compound verb with the same meaning as the separate verb plus its individuated direct object: fish for trout/trout fish, watch birdsbird watch, tend bar/bartend. Such incorporation has distinct defocalizing effect in discourse by reducing the informational status of the entity represented by the noun and reducing nominal categoriality. Nonincoporated forms, because they have full categoriality and are fully individuated in the discourse, may take subsequent pronouns, as illustrated in (1a); however, incorporated nouns do not take pronouns, as in (1b): 1a. Tom fished for trout. Bob fished for them, too. 1b. Tom trout fished,?? Bob fished for them, too. Pronominalization is disallowed in (1b), even though there is an overt surface noun to serve as a potential antecedent, because incorporation reduces the discourse role of the participants. Low categoriality of the nouns drivers from low categoriality of the discourse referent, and because incorporation reduce the semantic individuation is thereby constrained. Hopper and Thompson propose that all languages follow a radiances of categoriality of nouns in discourse, from presentative nouns (those that introduce new, individuated participants and have high categoriality) to anaphoric and contextually established forms (those that refer to antecedents and have reduced forms and intermediate categoriality) to nonreferring forms and zero anaphora (those with limited surface expression, no individuation, and low categoriality). Although their proposal is not pursued any further here, we should note that their observations support the view that the form class noun can be seen as a matter of the degree of the individuation of the entity encoded by noun. In Hopper and Thompson’s theory, the category of noun is motivated by discourse referentiality. 3.122. Temporal stability Givon (1979, 1984) proposes an ontological for linguistic categories and argues that the major grammatical from classes reflect a scale of the perceived temporal stability of the phonomena they donate. At one end of the scale of temporal stability are “experiences-or phenomenological clusters-which stay relatively stable over time, that is, those that over repeated scans appear to be roughly ‘the same” (1979:51). At the other end are “experiential clusters denoting rapid changes in the state of the universe. These are prototypically events or actions” (1979:52). In between are experiences of intermediate stability, sometimes stable, sometimes inchoative or changing. This scale directly manifests itself in grammatical classes: Nouns encode the most temporally stable, verbs the least temporally stable, and adjective in between, as in fig 3.1 (after Givon 1984):55): Nouns adjectives Most time-stable verbs least time-stable Givon observes that whereas all languages have both concrete and abstract nouns, the latter are always derived, most usually from verbs. This suggests that the basic noun in any language is that which encodes physically anchored, spatially bound entities; in contrast, verbs typically have “only existence in time” (1979:321). The temporal and nontemporal domains polarize experience and map respectively onto the major from class division in language: verb and noun. Moreover, many languages do not have a productive class of adjectives, and in such languages, the urden o modificatiton is taken up y nouns and verbs (Dixion 1982; ion 1979, 198; Schache 198;chap 10). When his happens, he more temporally sale attributes are often encoded as noun, and less temporally stable ones as verb, thus splitting the burden along the scale itself. In Toposa, the phenomenological attribute ‘big’ is encode like a verb (with a prefixed pronoun) because size reflect ontological growth, and hence is temporally unstable (givon 198:53) 2. a – polot. I big I am big. More accurately : I am bigging But the attribution of location, a temporally stable phenomenon, is encoded more like a noun (see Givon 1984:55 for analogous fact in the bantu languages). Adjective are thus ontologically between nouns and verbs on the scale of temporal stability and their encoding properties split along these same lines in languages that must use other from classes to take up the slack for missing adjectives: more durable properties are encoded like nouns, and less durable properties are encoded like verbs, exactly what should be expected from an intermediate class. One problem with Givon’s theory is its inconsistency when the analysis gets more fine-grained (Hopper and Thompson 1984:705). Some nouns are less time stable than others (compare motion, denoting a temporally unstable state, with house), and some verbs are more time-stable than others (compare sits, denoting a temporal constant, with unfolds). Givons responds that the scale of temporal stability is a hologram, where a phenomenon is reflected everywhere in all parts: within the form classes, the scale also applies full force, so nouns, for example, are generally more time stable, but temporal stability also saturates the class, and some nouns are more time stable than others (Givon 1984:55). In Givon’s defense, we should note that his generalization is really much less specific than what be claims or others attribute to him. Nouns do not encode temporally stable phenomena; rather the phenomena that nouns encode are not obliged to be temporally situated. What makes an entity an entity is its relative atemporality. This characteristic contrasts with that of verbs, which require temporal fixing. So time boundedness seems to be the gist of Givon’s time stability criterion for entities:” an entity x is edentical to itself if is identical only to itself but not to any other entity at time a and also at time b which directly follow time a” (Givon 1979:320). Crucial to individuated entities is their perceptual integrity, or constancy over time (see Jackendoff 1983: 42), unlike the notions encoded by verbs. Hence, for Givon categoriality is a direct reflection of the temporal stability of entities: their relative atemporality motivates their encoding as nouns. 3.123. Cognitive regions: Interconnectedness and density The role of temporal priority that Givon stresses is at the heart of Langacker’s (1987a, 1987b) characterization of the encoding of nouns. In his view, the mentally projected world that underlies reference is constituted by three kinds of object: regions, temporal relations, and atemporal relations, respectively the denotations of nouns, verbs and adjectives/adverb. Anoun designates a region in conceptual space (Langcker 1987b:58); a region is defined by interconnectedness and density.2 The simplest way to think of region is to imagine an array of points in “continuous extension along some parameter” (1987b: 198), a space of phenomenal continuity. The constituents that compose the space are intercounnected and define the space by this interconnection. The word book has two meanings that correspond to two different regions. Book may refer to the physical object (an array of physical points along the parameter of information). In both case, book designates an inert, internally unified space. A region also has density, compactness of the points in continuous extension. Density produces the prototype denotation for the category: the more compact the region, the more likely it is to instantiate the prototype. Langacker’s example here is the difference between archipelago and island. The former denotes a discontinuous region, a series of small islands functioning semantically as a single unit, where as the latter designates a continuous and dense region. Though each has the same semantic content, ‘body of land surrounded by water,’ island is more typical of the region expressed. Discontinuous and composite regions are less likely to surface as prototypes. In Langacker’s theory, the density and interconnectedness of regions in cognitive domains account for why nouns are remembered better acquired earlier, translated more easily across languages, and more stable under paraphrase. Their internal stability, derived from their interconnectedness and density, allows them to be relatively immune to linguistic context and surface consistently in the form class noun. 3.13. what nouns denote We can summarize the convergence of these three accounts of categories and their denotations rather straightforwardly. The categoriality o a noun is a function o thte relative stability of its typical denotation. For Hopper and Thompson, this is informational stability, individuated and salient discourse participants. For Givon, it is temporal stability, spatially anchored phenomena. For Langacker, it is cognitive stability, a dense and interconnected region in conceptual space. These semantic features breathe new life into the national definition of noun. Nouns may not always be persons, places, or things, but persons, places, and things almost always turn out to be nouns. Entities, relatively stable and atemporal discourse, ontological, and phenomena, motivate the form class. 3.2. Eight classes of semantic properties of entities We now have a sense of the basic issues involved in the semantic of nouns and entities. Here we turn to an enumeration of the properties that tend to be encoded as nouns. In section 3.1 we presented a picture of the broad content of the semantic representation of nouns: a relatively attemporal region in semantic or conceptual space. But languages often encode quite specific properties in their treatment of nouns, and so we must consider the more detailed content of their semantic representations. Our goal in this chapter is to take inventory of these components. We examine eight classes of semantic properties: specificity, boundedness, animacy, gender, kinship, social status, physical structure, and function. All these have more specific subelasses and characteristic grammatical reflexes that deserve our attention. The study of the semantic properties of entities and their grammatical manifestations is often carried out under the broader examination of noun classes and classifiers: particular morphological means to signal the semantic classes that nouns instantiate (Allan 1977; Denny 1976, 1986; Dixon 1982; Lakoff 1987). Elaborate classifier systems are found in a variety of genetically, and Swahili, gauges (Mandarin Chinese, American Sign Language, Chipewyan, and Swahili, e.g.): classifier take a rangeg of forms, form explicit coding in separate words to affixation by bound morphemes. Noun classifiers are clear instances of the encoding of specific semantic properties, and thus we resort to them as illustration. Classifiers either measure an entity by unit (mensurarls, e.., yard of X) or sort it by kind (sortals, e.g., row of X) (Lyons 1977: 463; homason 1972 is the seminal formal study). As Denny (1986) notes, classifiers, in combination with the entity, compositionally determine the meaning of the nouns they classify and so are good places, to observe the requirements of semantic theory (see chap 2). For example, in the phrase wad of paper, the sortal wad attributes a more specific property to the atemproal region denote by paper. The semantic representation of the whole expression, irregular ensemole of paper, is thus compositionally derived from the specific properties that make up its content. We want to account for the relatively few such specific properties that are actually instantiated in the vast range of possible properties that language could in principle encode. In many language. Classifier mark grammatical agreement and concord. In other languages, they mark discourse participants and function much like pronouns (Downing 1986; Hopper 1986). So the semantic properties they encode have a direct effect on the structural design of language and fall in line with the grammatical constraint. We now turn to an examination of the semantic properties that languages tend to encode as or on nouns. 3.21. Specificity 3.211. uniqueness and the specific/ nouns distinction An entity has been defined as an individuated, relatively attemporal region in conceptual space. Languages may also make reference to the degree of individuation of an entity. This is specificity, the uniqueness of the entity or, in more philosophical terms, the relative singularity of the denotation. He effect of specificity can be seen in the possible interpretations of the following sentence: 3. I’m looking for a man who speaks French. On one reading, a man who speaks French refers to a particular individual: ‘I’m looking for a particular man who speaks French.’ This is a specific reading. In another sense, however, a man who speaks French may refer to any person whatsoever: ‘I’m looking for any old man who speaks French.’ This is a nonspecific reading: the entity represented is any member of the class or kind so describe, but no one member in particular. The specific/ nonspecific distinction has clear grammatical ramifications. The