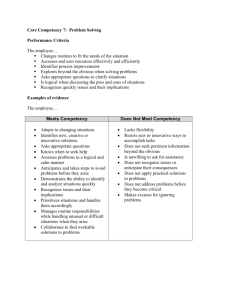

Responding to changing skill demands

advertisement