Professor Paul Rogers

advertisement

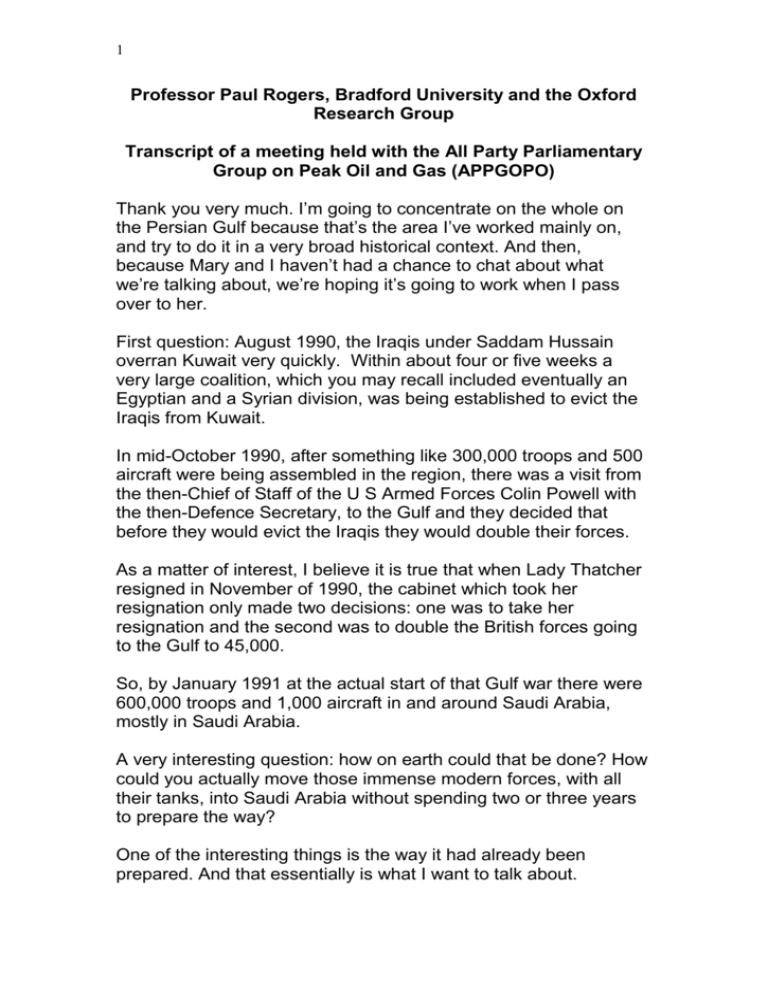

1 Professor Paul Rogers, Bradford University and the Oxford Research Group Transcript of a meeting held with the All Party Parliamentary Group on Peak Oil and Gas (APPGOPO) Thank you very much. I’m going to concentrate on the whole on the Persian Gulf because that’s the area I’ve worked mainly on, and try to do it in a very broad historical context. And then, because Mary and I haven’t had a chance to chat about what we’re talking about, we’re hoping it’s going to work when I pass over to her. First question: August 1990, the Iraqis under Saddam Hussain overran Kuwait very quickly. Within about four or five weeks a very large coalition, which you may recall included eventually an Egyptian and a Syrian division, was being established to evict the Iraqis from Kuwait. In mid-October 1990, after something like 300,000 troops and 500 aircraft were being assembled in the region, there was a visit from the then-Chief of Staff of the U S Armed Forces Colin Powell with the then-Defence Secretary, to the Gulf and they decided that before they would evict the Iraqis they would double their forces. As a matter of interest, I believe it is true that when Lady Thatcher resigned in November of 1990, the cabinet which took her resignation only made two decisions: one was to take her resignation and the second was to double the British forces going to the Gulf to 45,000. So, by January 1991 at the actual start of that Gulf war there were 600,000 troops and 1,000 aircraft in and around Saudi Arabia, mostly in Saudi Arabia. A very interesting question: how on earth could that be done? How could you actually move those immense modern forces, with all their tanks, into Saudi Arabia without spending two or three years to prepare the way? One of the interesting things is the way it had already been prepared. And that essentially is what I want to talk about. 2 If you go right back to the 1880s and 1890s, in very broad terms, oil exploration and development was primarily in very few locations: in the Caucasus, eventually the Dutch East Indies as it became, hence Royal Dutch Shell; Pennsylvania in Ohio, and, when the internal combustion engine came in and you had the real expansion of demand for oil, then in the United States it moved down to Oklahoma, Texas and California, and oil was developed as reserves in other parts of the world. Essentially, you go right through until the early post-second world war period, 1945, before there was any clear connection between issues of oil supplies and security. And in many ways, the first administration to be concerned with that was actually the Rosevelt administration, in 1944/45 because, from an American perspective, the sheer rate at which oil was being used by the US armed forces towards the end of the second world war meant that even though the United States had immense domestic supplies there was a risk they might not be adequate. In fact the first real American security interest in the Persian Gulf came in the late 1940s, curiously enough. For the next 25 years I would say, right through to the end of the 1960s, it really went back much more to commercial interests and essentially the rise of the United States oil companies in the Gulf; Aramco in Saudi Arabia; the Iranian consortium in the old Iran; these were much more commercially orientated and essentially there was not a great concern about oil security. You can date the change in that to one single day quite easily and that day was 17 October 1973. That was day eleven of the Yom Kippur-Ramadan War. And if you recall that was the war in which Syria and Egypt tried to turn around the gains that Israel had made in the Six-Day War in 1967 by attacking Israel, largely by surprise. The Syrians over the Golan Heights and the Egyptians across the [unintelligible] Line, the Suez Canal and into Sinai. With massive aid from the United States and extraordinary airlifts, the Israelis, within about eight or nine days, had turned back the assaults and in fact were starting to threaten the Egyptian Third Army, just to the west of the Suez Canal. The end result of that was huge concern, not in OPEC as a whole, but in the Arab members of OPEC, that inner group, OAPEC (the Organisation of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries). They met in 3 Kuwait on 16 and 17 October 1973 and decided, remarkably, on a very strong course of political action. They did three things. The first was that they put the price of oil up by 72%, 72% in one fell swoop. It was already a very strong bull market. The second thing was to announce they were going to cut back all their production by an average of 15%, to make sure the new price stuck; and the third thing was that they were going to embargo all oil supplies to the United States and to the Netherlands. The United States because the US was particularly strong in support for Israel, and the whole purpose was to put pressure on Israel to get an early ceasefire, to avoid the defeat of the Egyptian army. Why the Netherlands? The Dutch, to put it politely, were pretty fed up with this. Of course the reason [for this] was that Rotterdam was Europe’s key oil port and if you can actually embargo oil supplies to the Netherlands, that blocks supplies to Germany and some other countries. What was obviously very significant was that this oil price rise held. In fact, in a further series of rises, by May 1974 the overall price rise had been 450%. There was then a slow drop in oil prices and then another surge after the Iranian revolution in 1979/80. But it was at this point that the US military got far more interested. In a series of primarily classified studies done immediately after ‘74/’75 they sought to determine if the crisis had got even more severe and oil supplies had essentially been cut from the Persian Gulf, whether the US military could have intervened. And the result, very clearly, from one key, non-classified study, was that they couldn’t. A key Congressional research service report, carried out for one of the Senate sub-committees, looked at the security of oil supplies from an American perspective’ at a time in 1973/74, when in fact the US was only modestly dependent on imports (about 15% of its oil came from overseas). But the concern was the damage to the world economy if the oil tap was actually turned off. The end result of this was that eventually, by a lot of banging of heads together, the Carter administration managed to get the rapid deployment force established in 1979. The full title is Joint Rapid Deployment Task Force. It was very difficult because it meant the air force, the navy, the marines and the army all had to act together to have forces available for very rapid deployment. 4 Officially, this was anywhere in the world. Unofficially, it was all about the Persian Gulf. That was almost as far as it had gone until the end of the 70s, with the new oil price hike in the middle East, mainly as a result of the Iranian revolution; and the Reagan administration coming to power were hugely concerned now that almost a bulwark of the western defence system in the Persian Gulf was lost because of the Iranian revolution. The point here is that the concern about Persian Gulf oil supplies was not so much about any internal crisis but about Soviet intervention. These are the Cold War years, don’t forget. And one of the most extraordinary documents in a very long sequence in the United States (I still have a copy) was the military [unintelligible] statement for fiscal year 1982. That was the first [unintelligible] statements for the Reagan administration. Now many of us will remember those days. I mean, Mary was incredibly prominent in European nuclear disarmament and many of us expected with that new [unintelligible] statement, it would be all about the Soviet nuclear threat. In fact, it was dominated by the threat to America’s resources; and page after page was about the importance of the Persian Gulf oil supplies and what the Soviets might do if there was a major crisis and they moved in there. Of course with the Iranians having gone through a revolution, you really had [a lot of] paranoia. It was because of that, that the rapid deployment force was expanded to US central command in 1984. The end result of that was a singular programme not to base big forces in the area. That was not generally allowed, certainly by the Saudis, but to build facilities for very rapid deployment. So the big air bases that were built in Saudi Arabia in the mid-1980s were all four to six times bigger than the Royal Saudi Air Force needed and the end result of all of this [was] the very large wharfing facilities built at Al Jabile on the Red Sea. All these were available if there ever was any crisis involving a Soviet attempt to actually take major control of the Persian Gulf oil supplies. One of the people who was very prominent, one of the key American analysts pushing the idea of expanding the rapid deployment force to the central command level, a much bigger level, was a guy called Jeffrey Record, well-known analyst of Middle East affairs. He wrote a fascinating pamphlet in 1980, advocating the expansion of the rapid deployment force and he 5 said: OK your main reason [for this] would be the possibility of Soviet intervention but another possibility, for example, would be the Iraqis invading Kuwait. And that was published 10 years to the month before it actually happened. So essentially, you get an idea of this very key importance. And of course when you did get the invasion of Kuwait in 1990, it was Norman Schwarzkopf who was the Commander in Chief in central command, who led the operation to evict them. A very big coalition. Let me just continue, I’m two thirds of the way through and I just want a few more minutes to bring you up to date. One side-effect, in fact in many ways in the current context not a side-effect, of the results of that Gulf War was that the United States did indeed maintain its troops in Saudi Arabia from 1991 onwards. You have the huge airbase at Dhahran and many other facilities. And that in turn was one of the key motivations in the development of the al-Qaeda movement. You have the movement which had its origins in the mujahideen in Afghanistan against the Soviets and from their perspective they had pushed the Soviets out of Afghanistan, indeed had crippled a superpower. From their point of view, you now had ‘crusader forces’ in not just Afghanistan but the kingdom of the two holy places. And if you see the pattern of the development of al-Qaeda in the 1990s, it flowed very much from that US decision, leading on eventually to things like the Kobal Towers bomb towards the end of the 1990s, and all that has followed since. So there is a connection there. Let me finish though by just putting the current and possible future situations in context. The best way to do it is if you can imagine a rectangle of 1,000 miles north to south and 400 miles east to west. Imagine it’s put down over the North Sea, from the Dutch coast right through to north of Shetland. Under that imaginary rectangle you had, at the peak 15 years ago, about 3.5% of all the world’s oil supply. Quite a decent puddle by most standards and it kept Britain going for a while. It made Thatcherism survive, you might say; the Norwegians are still doing pretty well out of it. But imagine if you could take that imaginary rectangle and put it over the Persian Gulf, it would stretch from the Emirates in the south, it 6 would take in the Saudi fields, the offshore fields, the west Iranian fields, all of the Kuwaiti fields, the huge Rumaila oil field and all the Iraqi fields right up to the [unintelligible] axis. Under that rectangle you have about 62% of all the world’s oil. 62%. And of course it is high quality, easily exploitable oil. The only reason that the Iraqis, when they were retreating from Kuwait in March 1991, could set fire and burn the Kuwaiti oil fields was because they [the oil was] were coming out under natural pressure. They didn’t even have to pump the stuff out. It actually came out under its own gas pressure. So, essentially, this is pretty high quality oil and most of the world’s oil is there. I’m not arguing that the United States went in to terminate the Saddam Hussein regime five years ago simply because of Iraq’s oil. It’s true that Iraq has four times the reserves of the US but there were a complex set of motives. What I am saying is if you have an immense concentration, you add to that the changes in oil use. Now almost of all of western Europe is a very strong oil importer, as is Japan, as is South Korea. The United States is rather different. As I said, until the early 1970s the United States did not import much oil. It’s now almost up to the 60% level and will rise to over 70% by 2020, and that’s even allowing for the large reserves in north-east Alaska. The interesting one though is China. In 1993, as recently as that, just 15 years ago, China was entirely self-sufficient in oil. In two years’ time it will be importing half of all the oil it requires. And this does much to explain the very large agreement the Chinese have signed with the Ahmadinejad regime in Tehran over the last two or three years. Some of the biggest single oil export and production deals that we’ve seen anywhere in the world. So the trend very much is in a sense for the Persian Gulf to become more and more important in terms of oil strategy. Our dear friends in the Ministry of Defence are not very keen to say that the reason we’re going to construct the largest warships ever in the Royal Navy, the two big super-carriers, is because we will then have a capacity for worldwide expeditionary warfare, which currently is really only held by the United States. Those are the only size of carriers that could match the [unintelligible] super 7 carriers of the United States. So Britain certainly will have that capability, and has not had anything equivalent for about 35 years, to actually be involved in major conflicts, specifically I think in the Middle East. So I think where we are now is clearly a very important point in that the security of the Persian Gulf, from an oil perspective is extremely high - one takes the point that you have the Orinoco heavy oil deposits, you have the Canadian Tar Sands. But one must also remember that when I say 62% of the oil’s in the Gulf, most of the rest, another 18%, is in Russia, Khazakstan [and] Venezuela. And so when you put that all together you see this extraordinary preponderance. That doesn’t mean necessarily that you have enduring wars in the Persian Gulf but it’s absolutely critical to factor this in among all the other factors involved. What I would say is that there are far different, much more powerful arguments for moving away as fast as one can from oil addiction and those relate very much to climate change. But the key thing is, if you do actually diminish the dependency on oil for a country such as the United States, then in fact not only do you make a contribution to climate change control but also you reduce your reliance on a key strategic part of the world. One of the most fascinating papers I’ve seen in the last few years came from The Committee on the Present Danger, a very ‘hawkish’ group in the United States historically; and this was on oil security. When I saw it and printed it off, I looked at the heading and thought this is going to be all about bulking up the American forces in the Gulf but it was the complete opposite. What it said was that the dependence on Gulf oil, as it developed, and that’s quite apart from all the African and Latin American issues, as it developed, was actually a vulnerability to the United States. And this was The Committee on the Present Danger saying the US had to embark on a rapid programme to go into alternatives to oil. So it’s interesting where that thinking comes from at this present time. Thank you.