ESREA Biography and Life History Network

advertisement

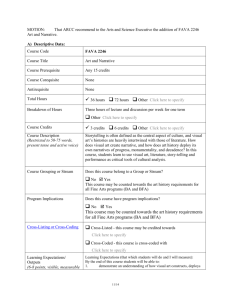

ESREA Biography and Life History Network European perspectives on Life History research: theory and practice of biographical narratives Geneva 7th to 10th of March 2002 Abstract Narrative Cognition and Construction - the Implications for Biographical narrative Research Marianne Horsdal Associate professor Institute of Educational Research University of Southern Denmark The ‘turn’ to biographical methods in the studies of lifelong learning and health care requires a more thorough and profound theoretical inquiry into the nature and meaning of narrative. The aim of this paper is to indicate a step in this direction. Issues will be addressed such as the acquisition of narrative competence, the significance of the interface of interpersonal experience and cognitive development, autonoetic memory, physical movement, and the social interaction and construction for sense-making and narrative competence. The epistemological approach to narrative has crucial implications for theories of learning and identity, and for the analytical strategies and outcomes of biographical narrative research. As an example, the role of primary metaphors in life-story narratives will be examined. A situated text Obviously, a narrative life-story interview is a situated text, influenced by the framing of its production and by the cultural space created between the narrator and the listener. However, a narrative interview differs from a qualitative or a semi-structured interview as the configuration of meaning, the plot and the story line of the narrative is created by the narrator alone, without any interruptions, or questioning on behalf of the interviewer until the end of story is clearly indicated by the narrator. Thus, the co-construction of the narrative is not eliminated, but the narrator’s line of thought or line of telling is not led astray by the explicit interests of the interviewer during the time of telling. What is told - or omitted, the sequence of episodes, the elaborations of detail or the brief mentioning, chief points and weight of significance, all of which effects the configuration of meaning - it is up to the narrator to decide within the situated context of telling. In this paper I’ll not go into detail to discuss the implications of the context of telling, how the preparations of the life-story construction, the framing of the interviewing enterprise (what kind of research in which fields are we talking about) and the face to face meeting between two people influence the life-story construction and the text production. Those are interesting and important elements of narrative biographical research, but the present focus lies elsewhere, namely on the nature and the meaning of the narrator’s construction, the narrated life, which is the central object of interest for the ‘biographical turn’. What am I - or anyone else - actually doing when I narrate my life? Life-story narratives and memory - facts or fiction? It is a naïve assumption to believe that biographical narrative research will reveal ‘what actually happened’ or ‘who the person really is’. What my, your, our, his or her life was (or is) like is a matter of complex interpretation. On the other hand, we do not expect our interviewees just to invent a story out of pure imagination for the occasion. We presume 1 they’ll give us a version of their lived experiences based on memory recall and cultural narratives that will count as a narrative construction of the self and interpretation of existence at the time of telling. Memory plays a crucial role in life-stories. If we couldn’t remember our past, there would be nothing to tell. But what is memory? Memory is often commonly - and wrongly - conceived as ‘stored’ in some kind of brain hard disc or mind attic. But we do not contain any files filled with past actions, thought, pictures, dreams and experiences. There is no ‘storage closet in the brain in which something is placed and then taken out when needed (Siegel 1999). What we usually think of as ‘memory’ refers to the way in which events can influence the brain in a way that allows for future activity to be altered in a specific manner. ‘Memory storage’ is the change in probability of activating a similar neural network pattern in the future. A pattern which resembles - but is not identical with - the pattern activated in the past. The probability is increased by repetition, but the construction process in remembering may be profoundly influenced by the present environment, the questioning context itself, and other factors, such as current emotions and our perception of the expectations of those listening to the response. Memory is not a static thing, but an active set of processes. (Siegel 1999:28) According to Siegel, the brain is also dynamic, meaning that it is forever in a state of change. An open, dynamic system is one that is in continual emergence with a changing environment and the changing state of its own activity. (Siegel 1999:17) We remember in order to anticipate the future, to determine what is going on and what will come next. Sigel makes a distinction between implicit and explicit memory. Implicit memory is active from the beginning of an infant’s life. It includes behavioural, emotional, perceptual, and perhaps somatosensory memory, and involves generalizations and mental models. Implicit memory is devoid of experience of self or of time. Reactivations - also later in life - lack a sense that something is being recalled. Rather it is experienced as the reality of our present experience. However, implicit memory can influence explicit memory. Explicit memory needs focal attention, the sensation of ‘remembering’ and develops in the second and third year of an infant’s life. Siegel refers to two forms of explicit memory: ‘semantic’ and ‘episodic’ (autobiographical or oneself in an episode in time) He says: “Wheeler, Stuss, and Tulving have summarized recent neuroimaging studies, which suggest that memory for facts (semantic memory) - including events - is functionally quite distinct from memory of the self across time (episodic) memory. Semantic memory allows for propositional representations - symbols of external or internal facts that can be declared with words or in graphic form and can be assessed as “true” or “false”. Such semantic knowledge has been called “noesis” and allows us to know about facts in the world. In contrast, autobiographical or episodic memory requires a capacity termed “autonoesis” (self-knowing)... The ability of the human mind to carry out what Tulving and colleagues have termed “mental time travel” - to have a sense of recollection of the self at a particular time in the past, awareness of the self in the lived present, and projections of the self into the imagined future - is the unique contribution of autonoetic consciousness. By the middle of the third year of life, a child has already begun to join caregivers in mutually constructed tales woven from their real-life-events and imagining. The richness of self-knowledge and autobiographical narratives appears to be mediated by the interpersonal dialogues in which caregivers co-construct narratives about external events and the internal subjective experience of the characters- In this way, we can hypothesize that attachment experiences - that is, communication with parents and other caregivers may directly enhance a child’s capacity for autonoetic consciousness.” (1999:35-36) 2 Tempero-spatial experience Before I go into a discussion of narrative construction in social interaction, I suggest a possible connection of autonoetic consciousness, mental time travel and bodily movement in space. Associated with the development of the functions of hippocampus, children experience a sense of sequencing, a temporal and spatial representation allowing us to remember where things are and when they were there, and what typically comes first and next in a given situation. This capacity is of vital importance for our actual travels in the environment. We do not have to tumble aimlessly around in confusion. About the same time as children manage to perform their independent journeys in the world, at first crawling, later on two feet, they gradually learn to recall their route of travel and find their way back and to imagine and plan for future excursions. Mental time travel is crucial for physical journeys.1 Lakoff and Johnson (1999: 30) talk about embodied spatial-relation concepts that make sense of space for us: A conceptual container schema (a bounded region in space) that has the structure of an inside, a boundary and an outside, and a source-path-goal schema. We are able to use both conceptual schemata across modalities and metaphorically. I assume we develop the ability to establish a cognitive map as a blending of the two schemata that allows us to conceive of a space of time, an extended context of a situation. The tempero-spatial extended context allows us to encompass past, present and future. We can contain a sequence, a day, a year, or a life-time in the focus of our attention. Thus, we are freed from ‘the prison of the present’ and at the same time able to transcend the fragmentation of experience. We can establish cohesion and coherence in a course of actions, events or motion, a precondition of planning. We do not have to start from scratch in each new interaction with environment. The future is not totally unpredictable although we always meet deviations from expectations to a smaller or greater degree. This cognitive development is the first step towards the ability to learn from experience by means of analogy or - in cases of greater deviations - negotiation of meaning.. This is the cognitive basis of narrative. Narratives are verbalized mental time travels associated with experiential locomotion. I suggest that autonoesis is conscious construction partly based on embodied unconscious mental activity. We realize the connection of bodily motion and cohesive sequencing (narrative cognition) when the spontaneous process is disturbed. We enter a room for some purpose, and forget what we were about to do, and go back to the initial position in order maybe to recall what we actually intended. Or we forget or displace some object and start figuring: “Now, what did I do, well, I came home, and then.” We orient ourselves as to where we are by narrating how we got there in order to be able to move on. “Mental time travel is an actively constructive process that creates the self within a social world.” (Siegel 1999:40). Narratives have an embodied cognitive basis totally dependent on interpersonal experience and social interaction. Learning narration in interaction Narrative cognition and construction is developed in a cultural space between the infant and its caregivers. Typically, caregivers verbalize their interactions with children, e.g. when changing diapers. (Aukrust 1995) Aukrust talks of ‘here-and-now narratives’ when a current sequence of action is narrated in order to help children to make sense of and understand what is going on. Gradually the narratives of caregivers also encompass events of ‘there-and-then’ , what is going to happen later or what happened earlier in a similar or a different context. The 1 Referring to Squire (1987) Siegel notes that loss of hippocampal functioning in animals for example leads to loss of memory for running a maze. (1999:32) 3 temporo-spatial context is gradually increased providing for a wider narrative construction of coherence and sense-making. Parents and caregivers also frequently interpret the mental state of the infant verbally. This actually assists the child verbally to express emotions and mental states and perhaps to understand others’ emotions.2 Soon, the infant will participate more actively in the dialogues. The adults intervene in the children’s narratives with attribution of meaning ( more or less tentatively completing the sentences and suggesting the intentional sense-making on behalf of the children). Later on caregivers also employ a practice of over-hearing, and children will eventually learn not to express in their narratives what is well-known for both partners of a dialogue. (Aukrust 1995) The children’s narrative competences are gradually developed in social interaction in specific cultural contexts. Narratives are social constructions, and narration involves essential features of social interaction and discourse. “The teller produces verbal and nonverbal signals that are received by the listener, and then similar forms of communication are sent back to the teller. This intricate dance requires that both persons have the complex capacity to read social signals, to share the concept of the existence of a subjective experience of mind, and to agree to participate in culturally accepted rules of discourse. Stories are thus socially coconstructed.” (Siegel 1999:52) Narratives exist in all societies, but with a great cultural variety as to what, how, where and to whom we narrate. Small children appreciate repetitions, repeated interactions, plays, songs etc. Not surprisingly, considering the novelty of the cultural environment, do they enjoy recognitions. Any new acquisition of coherence is difficult. Even the task of making sense of the practices of everyday life demands a narrative effort (Nelson 1989). By and by, frequently repeated practices and sequenced routines can become tacit and implicit, until something unusual happens that make us start reflecting and negotiate meaning using our cultural repertoire of narratives for sense-making and reconstruction. Vicarious experience We construct and listen to narratives to make sense of our experiences and the experience of others. Stories are told and shared as a reservoir of vicarious experience. Stories are mental time travels in imaginary contexts, in different worlds, narrated from different perspectives. Rukmini Bhaya Nair, an Indian researcher, describes the human possibility of narrative cognition as a great evolutionary progress, increasing our chances of survival. Our knowledge of environment is not limited to our own direct experiences but extended by the means of narratives, which give us a wider range of possible interaction. Listening to a story may result in a little fear and increased hearth beat. However, we are as listeners not exposed to the dangers of the protagonist of the narrative. Narratives provide us with a wider horizon, and allow us to identify with experiences of others and to try to interpret and understand other minds, emotions and actions, and stories invite different perspectives. From the infant’s arrival in a family and throughout life we are entering social contexts in which social interaction was already taking place prior to our arrival, just like entering a stage where the play had started before our participation in action. Through narratives we get “ Some families participate in frequent co-construction of narrative and elaborate memory talk. In reinforcing this kind of experience, parents may facilitate their children’s ability to describe their memories, as well as their imagination. In a similar fashion, children raised in families that discussed people’s emotional reactions tended to be more interested in and understand others’ emotions.” (Siegel 1999:46) 4 2 connected to the cultural contexts and to previous interactions. Our own stories of recalled experiences are extended by other narratives. We are situated in narratives of interactions we personally do not remember. We are narrated from the perspectives of others, and we get connected to other narratives, family narratives, organizational narratives and cultural narratives.3 All those narratives provide different interpretational frameworks and may be a part of our identity construction. Emerging selves and life-story narratives As Siegel correctly states: “ The notion of a single narrative for a human life is too limited, as memory and the nature of our selves are forever changing.” (1999:63). We recall many different selves from the past. The remembered self is multilayered, and we narrate our lives from the standpoint of multiple selves. Narrative recollection is the opportunity for those varied states to be created anew in the present. “As our present state of mind reflects the social context in which our narrative is being told, we weave together a tapestry of selected recollections and imagined details to create a story driven by past events as well as by the need to engage our listeners. Thus the expectations of the audience play a major role in the tone of storytelling. This social nature of narrative means that the remembering self is perpetually in a process of creating itself within new social contexts.” (Ibid.) Narrative construction is an ongoing activity, integrating and reconfiguring the emerging selves in order to achieve sense-making and create coherence, anticipating the future by means of analogy and facing new interactions. The construction of narrative identity is a dynamic process of negotiation and renegotiation in cultural space and never fully accomplished. Therefore, life-stories are polyphonic and dialogical. From his standpoint of neurobiology Siegel frequently underlines the significance of interpersonal relationships. “Emotional attunement, reflective dialogue, co-construction of narrative, memory talk, and the interactive repair of disruptions in connection are all fundamental elements of secure attachment and of effective relationships” (1999:336) This is of great importance in early childhood, but “creating coherence is a lifetime project. Integration is thus a process, not a final accomplishment. It is a verb, not a noun.” (Ibid.) Throughout life interpersonal relationships and cooperate narratives play a crucial role. Pedagogical implications Accordingly, the development of narrative competences is of vital importance from a psychological perspective. Narrative competence seems to facilitate autonoetic consciousness, regulation of emotion, integration of mental states, understanding other minds, cohesion of experience, identity work and the abilities to plan for the future. The indispensable interpersonal cooperation in narrative development points to the significance of implementing narratives in pedagogical practice in substantial ways. Narratives should play a significant role in children’s interactions with parents, caregivers and educators. Narrative competence has also been underlined from a learning perspective. Bruner (1996) has strongly emphasized narrative competences regarding the abilities for reflection, Kerby (1991) says: “The stories we tell of ourselves are determined not only by how other people narrate us but also by our language and the genres of storytelling inherited from our traditions. Indeed, much of our selfnarrating is a matter of becoming conscious of the narratives that we already live with and in - for example, our roles in the family and in the broader sociopolitical arena. It seems true to say that we have already been narrated from a third-person perspective prior to our even gaining the competence for self-narration. Such external narratives will understandably set up expectations and constraints on our personal self-descriptions, and they significantly contribute to the material from which our own narratives are derived.” (p. 6) 5 3 negotiation of meaning and metacognition. He stresses the importance of seeing different perspectives. A central educational concern in a changing world “will be how to create in the young an appreciation of the fact that many worlds are possible, that meaning and reality are created and not discovered, that negotiation is the art of constructing new meanings by which individuals can regulate their relations with each other” (1986:149) The last quotation indicates the issue of citizenship education. I have elsewhere (Horsdal 2000, 2001, 2002) discussed the significance of narrative competence regarding active, democratic citizenship, also in connection with attentiveness and sensitivity towards different codes, open-mindedness, participation, belonging and identity-work. Narrative competence can be encouraged, just as our narrative abilities may deteriorate in an impoverished environment (Horsdal 2002). Poor narrative competences entail difficulties when we are to make sense of our lives and the surrounding world. And this may inhibit our ability to learn how to learn. However, life-story work in a pedagogical context may be an equivocal enterprise when carried out from too simplified assumptions. The suggestibility of the human mind must be considered as well as the vulnerability of some people towards pressure. Any biographical narrative construction can have an impact on later self-interpretations. As mentioned earlier, the concept of The life-story is far too narrow. The construction of one lifestory attending the individual may inhibit further renegotiation and reconfigurations of the past and thus imposes a prefixed identity and unnegotiable interpretations and increased impact of past events on future decisions. Narratives can be hegemonic and authoritative like for instance reports and institutional accounts. Life-story narratives constructed in hierarchical and unequal settings are often implicitly canonical. Implications for biographical narrative research What is the narrator actually doing when responding to the task of a narrative interview: “Please, tell your life-story from the beginning up till today?” The woven tapestry constructed in the life-story narrative will be influenced by the following elements: The situated narrative interview The cultural space between teller and listener Verbal and nonverbal signals Assumed expectations of the interviewer Research framework Mental state of the teller The wider situational context of the teller The emerging self, effected by the actual life situation, actual events, happenings, considerations and plans This determines the perspective from which the story is told. And the present context will influence the weight of substance and selection of recall and telling and the configuration of the narrative. The narrative competence of the teller The narrative will bear the impact of former frequent retellings or of an unfamiliar performance. Narrative competence also influences creation of coherence, sense-making and negotiation abilities. Cultural narratives, interpretative frameworks 6 Collective world visions and identities mark the narration in significant ways. Framings according to gender, class, religion, ideology or wide-spread theories such as individual developmental psychology influence genre and narrative causation. Life-story narratives often display conflicting cultural narratives. Past experiences in different cultural contexts. Emotions, values, intentions, actions and happenings in former interactional contexts recollected and reconstructed make up the version of the past, the ‘there and then’ of the narrative. From the perspective of ‘here and now’, the time of enunciation, a life-story narrative constructs a path from the beginning to the end of telling. The story line- no matter how winded - often mirrors the experience of a trajectory between places and interactional contexts (there and then) using the Life Is a Journey metaphor.4 The experience of participation, positioning, interaction and affiliation within each social context (such as family, schools, workplaces, interpersonal relationships) influence the identity construction of the narrative. Furthermore, contexts may be considered and analysed as learning communities from the perspective of situated learning (Lave and Wenger 1999). Whether formal, non-formal or informal learning contexts, the quality and character of interpersonal relationships seems to have a decisive impact on the experience of learning. Typically, the timespan of each context is emotionally evaluated in the narration. The influence from one contexts to the following, the impact of past experience on the present is, however, recreated from the present perspective. Briefly defined, a life-story is a situated narrative - a tempero-spatial - experientially embodied construction of self and identity in a social world and an interpretation of existence including world view, values and attitudes. The significance of narrative as verbally constructed mental time travel for coherence and integration of the social self across space and time in favour of an improved capacity for anticipation and planning is obvious, because the construction of a narrative configuration of meaning and the integration it entails is a process of reorganization on the fertile ground between order and chaos. We learn as a new self emerges in a reconfiguration of meaning. We are rather lost if we fail to do it, and rigid repetitions are of limited use in a changing world. The individual journey through life reconstructed in the life-story narrative is a tentative version. “Sense making never gets dull, because people do not simply ‘repeat’ the past, nor do they invent the future out of thin air.” (Steyart and Bowen 1997) At the same time, the performance of narrating life often implies - due to the complex character of memory and autonoetic consciousness - a detailed and elaborated construction of episodes of great cultural interest. Thus, narratives present the versatility of experience so rich, compared to a lot of traditionally produced empirical data. In 1956 my parents got a car. Then we had Sunday trips every Sunday after church and Sunday school. My grandmother had paid half of the car, so, of course, she had to come along. Usually, we brought some coffee, and then we unfolded the folding-chairs, but only my father’s chair had a back rest. (Woman born 1946) (Horsdal 2000) Primary metaphors in life-stories A variety of the Life Is a Journey metaphor and the Time Is Motion metaphor (Lakoff and Johnson 1999) are frequently found in life-story narratives. Narrators come to cross-roads, 4 Life-story narratives told by old farmers who stayed their whole life where they were born, use a figure-ground reversal: the protagonist stays and time moves, and the changing of seasons and other time markers are used to configure the narrative. 7 stop, move on, follow the footsteps of others or find their own way. They drift along or stand on their own two feet. They meet obstacles on their way and have their ups and downs (High Is Up). Those metaphors show how our minds and spontaneous ways of thinking are embodied5. And I have found certain patterns of metaphors in different life-story narratives that reveal information about how the individual narrator experiences his situation and interaction with the environment. The metaphors are - together with a range of other interpretational approaches (Horsdal 2002) -one of the ways to analyse the interpretation of self and existence of the narratives. A young girl whose life-story narrative I have analysed in Grundtvig Sokrates II - active Citizenship and the Non-formal Education, 2000, is frequently talking about her jumping from one context to the other. She is reflecting and negotiating the shifts, the lack of endurance and commitment when a social situation seems unsatisfactory. I went to university, but I was completely unable to keep up with the others. They had been on the go for six month... So I thought, What on earth am I doing here? I worked there for six months. I remember the very first day. I thought that it was pretty awful. I thought that they were idiotic, and I remember that I thought that I was not going to stay. Still I did. I think it is a very good idea to try something other than just going to school. I remember the first day there. There were visitors, family, and we had had lunch. They ask me some questions, and it is very difficult to explain who I am etc. I had the afternoon off and went for a walk. I remember thinking that I felt like a servant and what on earth was I doing there? I remember writing to my boyfriend that I felt that everything was quite horrible. I remember vividly that walk - was I going to have a good cry or just laugh? Now it is great fun to look back, because there were all these small obstacles to be coped with. It had something to do with the fact that you were unable to express your thoughts and then you feel tiny little in a foreign country. Luckily I stayed. I think that many of these experiences have been very important to me. In the last two examples the narrator is negotiating and integrating different selves, mental states at different times, that is, reflecting and reconfiguring the multiple selves. In the following quotation she is negotiating the problem of jumping by introducing different and sometimes contradictory forms of narrative causation from the perspectives of different cultural narratives that are part of the polyphony of her narrative (mainly one framing associated with her father and grandmother and a generational framing): To so many of us the problem is that we have so many possibilities, and it is extremely difficult to choose among these possibilities. It is a luxury problem, I know, but it really is a great problem to many. You think all the time - Am I doing the right thing? And this applies both to my boyfriend and my education, yes, to almost anything you do: “What do I miss when I choose this?” Maybe it is a problem when we just rush [in Danish ‘jump’] around the way we do all the time, “now I want to try this” and “now I also want to try that” - because, who are eventually going to be the driving force of society? I have thought a lot about this. Just look at myself: for one year I was a member of the Young Social-democrats, then I got tired of that and quit. I am rather typical of the young ones, I think. I begin doing something and go on for a bit, and then I quit. Is it good or bad that you just run [jump] from one thing to another? Why stay if you do not feel like it. Still, who is going to be the moving spirit if we all just quit?... You don’t really know what you want - you have tried the university - maybe 5 8 See also Gibbs 1994 two or three times. This is typical of many students at college. What, really, do I think myself? What do I want? Well, maybe you have an obligation towards society. My father always maintained that. The social conditions of the older generations didn’t allow for this degree of individual planning of which path to choose or whether to stay, quit, jump and change track. The contemporary challenges, e.g. the acquired reflectivity, competences for participation in different cultural contexts and for negotiation are apparent in the use of metaphors in narrative self-constructions. Conclusions ‘The biographical turn’ has appeared in different academic fields such as sociology, psychology, educational studies and cultural studies. ‘The narrative turn’ has an even wider field of application. I find cross-disciplined studies very interesting and challenging. A decade’s study of life-story narratives has accomplished fascinating meetings with a wide range of theoretical and methodological positions, and I have been inspired by readings in philosophy and literature, organizational analysis, social constructionism, social interactionism, discourse theory and many others, although I am working with educational research. The latest meeting introduced in this paper was with neurobiology. Believing our knowledge to be tentative and situated I want to suggest the value of critical reconfigurations of our own narratives of the field from various perspectives. Just like listening to so many life-stories create a versatile and spacious view of human experience. However, a number of cultural narratives also permeate the academic world with doubtful and questionable assumptions in need of theoretical and critical negotiation. Fortunately for years now, modernist ideas such as the misleading concept of the autonomous, individual subject, the sharp distinction between subject and object and positivistic theories of research have been deconstructed, and new theoretical approaches have enriched our perspectives emphasizing the impact of relationships and discursive constructions. Yet, social constuctionism and discursive psychology sometimes neglect that we have a body that moves and an embodied mind (Horsdal 2002). The experiences of the single human being are both social and embodied, our individual neural associational patterns are unique as our pathways through life of social interaction reflected in life-story narratives. References: Aukrust, Vibeke Grøver, Fortellinger fra stellerommet. To’åringer i barnehage; en studie av språkbruk - innhold og struktur, Universitetet i Oslo, Pedagogisk Forskningsinstitutt, rapport nr. 4/95, 1995 Bruner, Jerome, Actual Minds, Possible World, Harvard University Press, 1986 Bruner, Jerome, Act of Meaning, Harvard University Press, 1990 Bruner, Jerome, The Culture of Education, Harvard University Press 1996 Gibbs, Raymond W.,The Poetics of Mind: Fugurative thought, language, and understanding, Cambridge University Press 1994 Holstein, James A. and Gubrium, Constructing the Life Course, New York 2000. Holstein, James A. and Gubrium, The Self We Live By, Oxford University Press, 2000 Horsdal, Marianne, Livets Fortællinger, Borgen 1999 Horsdal, Marianne, Vilje og Vilkår, Identitet, læring og demokrati, Borgen 2000 Horsdal, Marianne, “Democratic Citizenship and the Meeting of Cultures” in Schemmann and Bron Jr, Adult Education and Democratic Citizenship IV, Krakow 2001 Horsdal, Marianne, Grundtvig Sokrates II - active Citizenship and the Non-formal Education, Højskolernes Hus (www.hojskolerne.dk) 2002 9 Horsdal, Marianne, “Affiliation and Participation - Narrative Identity” in Korsgaard, Walter, Andersen, Learning for Democratic Citizenship, The Danish University of Education, 2002 Kerby, Anthony Paul, Narrative and the Self, Indiana University Press, 1991 Lakoff, George and Mark Johnson, Philosophy in the Flesh, Basic Books, 1999 Lave Jean and Etienne Wenger, Situated Learning, Cambridge University Press, 1991 Nair, Rukmini Bhaya, Narrative Gravity : Conversation, Cognition, Culture, 2001 Nelson, Katherine, Narratives from the Crib, Harvard University Press, 1989 Siegel, Daniel J., The Developing Mind. Toward a Neurobiology of Interpersonal Experience, The Guilford Press, 1999 Steyaert, Chris and Bouwen, Rene, “Telling stories of Entrepreneurship. Towards a narrative contextual epistemology for entrepreneural studies. In, Donckels and Miettinen, Entrepreneurship and SME Research: On its way to the Next Millenium, Aldershot, Ashgate, 1997 10