From Eden to Eschaton: The Divine Mission of

advertisement

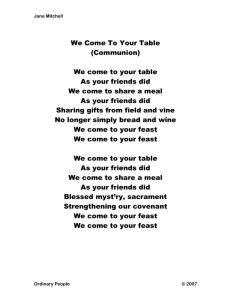

R. York Moore From Eden to Eschaton: The Divine Mission of Restoring Lost Community Feast motif for the controlling image for all divine mission and missional aspiration. An examination of Exodus 24, Esther 8, Mark 14, and Acts 2 in light of the eschatological feast of Isaiah 25, Revelation 19 and 21 From Eden to Eschaton: The Divine Mission of Restoring Lost Community Page 1 Table of Contents Introduction: Feast Imagery as the Motif for Divine Missional Action ........................................................ 3 Definition of Terminology & Paper Structure .............................................................................................. 3 A Shift in Emphasis for Mission: Community Centered Mission ................................................................ 4 Meal on the Mountain of God: Exodus 24 .................................................................................................... 5 Feasting and the In-Gathering of the Nations: Esther 8:15-17 ..................................................................... 7 The Lord’s Table as Montage for All Divine Mission: Mark 14:22-26 ....................................................... 9 The Eschaton Feast in Our Time: Acts 2:42-47 .......................................................................................... 11 Toward Holistic Gospel Proclamation: Application for Ministry Context ................................................... 13 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................................... 14 Sources Cited .............................................................................................................................................. 15 From Eden to Eschaton: The Divine Mission of Restoring Lost Community Page 2 Introduction: Feast Imagery as the Motif for Divine Missional Action All of divine history has been purposely heading toward a climactic end point, a set of events that, together, portray the ultimate ‘dream of God.’ The deliberative and cumulative actions of God throughout the narrative of Scripture reveal that God’s dream revolves around themes of community and celebration-themes most vividly seen in the Biblical feast imagery. The thesis of this paper, therefore, is that divine mission has as its aim a state of relational existence for God and his creation that is characterized by community and celebration and that in this, the central image for the ultimate fulfillment of God’s missional actions is seen in the imagery of the feast. In support of this thesis, this paper’s argument is that the feast motif in Scripture is the primary or controlling image for the ultimate fulfillment of the missional activity and dream of God as the portrayal of historic feast descriptions find their ultimate expression in the climactic, eschatological event of the wedding feast of the Lamb. Definition of Terminology & Paper Structure This paper will refer repeatedly to the three primary concepts in exploring its thesis and argument: divine aspiration; divine mission, and; the dream of God. By divine aspiration it is meant here the cohesive and collective personal ‘wants’ God. By divine mission it is meant here the determinative actions of God revealed in Scripture that demonstrate his divine aspirations and their end goal. It is this end goal which will be referred to here as the ‘dream of God.’ This dream, it will be argued, is seen most vividly in the eschatological wedding feast of the Lamb and the associated in-gathering of the nations. In this paper, we will examine four passages of Scripture as they demonstrate the divine aspiration and missional activity of God. In the first testament, we will look at the feast with the leaders of Israel and God in Exodus 24 and the feasting and in-gathering of the nations in Esther 8. In the second testament, we will examine From Eden to Eschaton: The Divine Mission of Restoring Lost Community Page 3 the Lord’s table in Mark 14 as a foreshadowing of the great eschatological wedding feast and the first Church in Acts 2 as an expression of the eschatological community of God. Finally, application considerations will be given to my current ministry context as an abolitionist and evangelist. A Shift in Emphasis for Mission: Community Centered Mission While many works on the concept of divine mission revolve around the nature of God’s work through the actions of the Church and whether or not such actions ought to be interpreted normatively as centrifugal (externally focused on actively bringing the message of Christ to those outside the community of faith)1 or centripetal (passively demonstrating the attractiveness of faith in Christ through the character of community)2, little has been written as to the ultimate aspirations of divine mission outside of the benefit to those being saved. Considering the divine aspiration in missional action requires us to take note of the repetitive intent of God to commune with humanity. In the opening passages of Scripture, we see these aspirations portrayed for us in God’s providence of food and the role food plays in fellowship. We read in Genesis 1:29, “Then God said, “I give you every seed-bearing plant on the face of the whole earth and every tree that has fruit with seed in it. They will be yours for food.”3 It is not incidental, then, that the partaking of a meal of deception and fraud with the devil later is a violation of this meal covenant God makes with Adam and Eve, “When the woman saw that the fruit of the tree was 1 Walter C. Kaiser, Mission in the Old Testament : Israel as a Light to the Nations (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Books, 2000), 9, 35. 2 Ibid., 83. 3 The Holy Bible : New International Version, Containing the Old Testament and the New Testament, Textbook ed. ed. (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan Bible Publishers, 1984). From Eden to Eschaton: The Divine Mission of Restoring Lost Community Page 4 good for food and pleasing to the eye, and also desirable for gaining wisdom, she took some and ate it. She also gave some to her husband, who was with her, and he ate it.” (Gen. 3:6).4 Food is the means by which rebellion against God was expressed and it becomes the controlling image of victory moving forward in divine mission. The role of food is central in the story of divine mission from the earliest pages of Scripture. In every covenant made between God and humans, a meal is involved in its execution or its commemoration. Dr. Robert Gallagher documents the importance of the commemorative meal in “the promise” of God’s commitment to community with his people in Jeremiah 31:33; 2 Corinthians 6:16 (“I will be their God, and they will be my people”)5. What is often missed, however, is the strategic repetition of this promise at the most important commemorative meal of divine history“And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, “Look! God’s dwelling place is now among the people, and he will dwell with them. They will be his people, and God himself will be with them and be their God.” (Rev. 21:3).6 This repetition at the eschatological wedding feast of the Lamb helps demonstrate the centrality commemorative meal celebration in divine mission as we will see. The role of meals in marking inflection points in God’s missional activity begins with the Adamic covenant and continues until its ultimate fulfillment at the wedding feast of the Lamb. Between these two events stand a litany of foreshadowing meal events which demonstrate God’s missional aspirations. Meal on the Mountain of God: Exodus 24 Consider the surprising meal on the mountain of God in Exodus 24: “9Moses and Aaron, Nadab and Abihu, and the seventy elders of Israel went up 10 and saw the God of Israel. Under his feet was something like a pavement made of lapis lazuli, 4 Ibid. Robert L. Gallagher, "The Hebraic Covenant as a Model for Contextualizatoin," Missions & Intercultural Studies (Wheaton, IL: Wheaton College Graduate School, Unknown), 7, 14. 6 The Holy Bible : New International Version, Containing the Old Testament and the New Testament. 5 From Eden to Eschaton: The Divine Mission of Restoring Lost Community Page 5 as bright blue as the sky. 11 But God did not raise his hand against these leaders of the Israelites; they saw God, and they ate and drank.” (Ex. 24:9-11, NIV).7 Despite a seeming contradictory command not to approach God in verse 1, in Ex. 24:9-11, the entire group of leaders and elders of Israel go up, see God and eat and drink with him! This breathtaking foreshadowing of the future eschatological meal provides us with a glimpse into the heart of God and his ultimate aspirations. God does not raise his hand against the leaders and a meal of celebration ensues. This meal points to the restorative feast of God to come. In Isaiah 25:6-8, we are provided with more of the details associated with the wedding feast of the Lamb: “On this mountain the LORD Almighty will prepare a feast of rich food for all peoples, a banquet of aged wine—the best of meats and the finest of wines. 7 On this mountain he will destroy the shroud that enfolds all peoples, the sheet that covers all nations; 8 he will swallow up death forever. The Sovereign LORD will wipe away the tears from all faces; he will remove his people’s disgrace from all the earth. The LORD has spoken.”8 This mountain top event and the associated meal are undoubtedly the same place and event John speaks of in Revelation 21:2-4 and 9b-10, “2 I saw the Holy City, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride beautifully dressed for her husband. 3 And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, “Look! God’s dwelling place is now among the people, and he will dwell with them. They will be his people, and God himself will be with them and be their God. 4 ‘He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death’ or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away.”” (Rev. 21:1-4).9 ““Come, I will show you the bride, the wife of the Lamb.” 10 And he carried me away in the Spirit to a mountain great and high, and showed me the Holy City, Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God.”10 (Rev. 21:9b-10).11 In Exodus 24, the leaders of Israel experience a foretaste of the fulfillment of the dream of God, the final completion of his missional aspirations in accomplishing community. This celebration points to God’s overarching desire and missiological intent to establish joy and connection as 7 Ibid. Ibid. 9 Ibid. 10 Ibid. 11 Ibid. 8 From Eden to Eschaton: The Divine Mission of Restoring Lost Community Page 6 seen through feasting. Understanding that missional activity is not an end in and of itself, but rather a means to arriving at a state where the nations are able to eat and drink with God is well argued by John Piper, “Mission is not first and ultimate; God is,” and “Missions is not God’s ultimate goal, worship is.”12 Unfortunately, Piper and others fail to realize that worship for God is much more a matter of feasting and celebration in the context of community rather than “…right affections in the heart toward God, rooted in right thoughts in the head about God, becoming visible in right actions of the body reflecting God.”13 The emphasis on ‘rightness’ is eclipsed in the dream of God by a people ‘made right’ by no means of their own, but rather because they “…have washed their robes and made them white in the blood of the Lamb.” (Rev.7:14b)14. The feast in Exodus 24 helps us see the missional aim of God as a state of relational existence with his creation that is characterized by community and celebration. Feasting and the In-Gathering of the Nations: Esther 8:15-17 The missional activity and aspirations of God culminate in feasting and joy-ultimately God is after establishing joy for his people and the in-gathering of the nations. After the judgment of Haman and the emancipation of the Jews in Esther, King Xerxes provides the Jews the sovereign right to assemble and to protect themselves. This radical change and deliverance leads to the following description of the Jew’s response: “When Mordecai left the king’s presence, he was wearing royal garments of blue and white, a large crown of gold and a purple robe of fine linen. And the city of Susa held a joyous celebration. 16 For the Jews it was a time of happiness and joy, gladness and honor. 17 In every province and in every city to which the edict of the king came, there was joy and gladness among the Jews, with feasting and celebrating. And many people of 12 John Piper, Let the Nations Be Glad! : The Supremacy of God in Missions, 3rd ed. rev. and expanded. ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2010), 38-39. 13 Ibid., 231. 14 The Holy Bible : New International Version, Containing the Old Testament and the New Testament. From Eden to Eschaton: The Divine Mission of Restoring Lost Community Page 7 other nationalities became Jews because fear of the Jews had seized them.” (Esther 8:1517).15 While the narrative of Esther is less blatant than the Exodus text, the missional activity and aspirations of God in Esther are unmistakable. The great enemy of the Jews had been defeated, they were vindicated and joy and feasting erupts. This feasting, joy and celebration mirror the progression in Revelation 18-20 as the enemies of God are defeated. Most notably we read, “Then I heard what sounded like a great multitude, like the roar of rushing waters and like loud peals of thunder, shouting: “Hallelujah! For our Lord God Almighty reigns. 7 Let us rejoice and be glad and give him glory! For the wedding of the Lamb has come, and his bride has made herself ready. 8 Fine linen, bright and clean, was given her to wear.” (Fine linen stands for the righteous acts of God’s holy people.) 9 Then the angel said to me, “Write this: Blessed are those who are invited to the wedding supper of the Lamb!” And he added, “These are the true words of God.”” (Rev. 19:6-9) 16 While it may seem like a leap to draw the parallel between Esther 8 and Revelation 19, both demonstrate the rejoicing and enfolding of the nations that comes with the eradication of the enemies of God. In Esther, God is at work to free his people from their enemy, Haman (a name cursed amongst the Jews to this day)17. As this freedom comes it produces joy and feasting as well as the missional result of an enfolding of ‘other nationalities.’ In Revelation, as Babylon is destroyed, the wedding feast is announced and praise bursts from a ‘great multitude,’ a phrase elsewhere used to refer to the in-gathered nations of the world (Rev. 7:9; Rev. 17:15). The emphasis on the inclusion of all nations, tribes, people and languages, speaks to the nature of God’s ultimate feast of celebration. While Arthur Glasser, in his seminal work Announcing the Kingdom, points out that the phrase in Esther 8, ‘became Jews,’ appears only this once in all of the first testament, he persuasively argues throughout his work for the normative centrifugal 15 Ibid. Ibid. 17 Louis Jacobs, The Book of Jewish Practices (Springfield, NJ: Berhman House, 1987), 124. 16 From Eden to Eschaton: The Divine Mission of Restoring Lost Community Page 8 missional activity of God in both the first and second testaments.18 The narrative in Esther is a fitting place for the phrase ‘became Jews’ to appear as it is the most secular book from a literary perspective in the first testament. It is in the context of feasting and joy that we see the accomplishment of the God’s missional aspirations to enfold the nations in both Esther and Revelation 19. Finally, a note on exegesis and developing the argued missiological principle of this treatise: While I agree with David Bosch’s assertion that “…it is impossible to infer missionary principles or models in a direct manner from isolated texts or passages,”19 when we see such strong, repetitive motifs emerge in multiple and significant inflection points throughout Scripture, such principles become a part of the architecture in how we interpret the missional aspirations and actions of God. Between Exodus 24, Ruth 8 and the Isaiah and Revelation texts we see such inflection points, helping us understand the normative missiological intent of God. The Lord’s Table as Montage for All Divine Mission: Mark 14:22-26 Throughout the gospels, Jesus told many stories of a great wedding banquet, the marriage supper of the Lamb, the marriage feast for the king’s son, and the man who had no wedding garment. Glasser, in Announcing the Kingdom, says that the wedding feast parables, “…all refer in one way or other to the same apocalyptic event (Luke 14:16; Rev. 19:9; Matt. 22:2, 11). And yet the impression is given that the festive spirit of that future banquet can be enjoyed even now, as it is connected with the mission of the church.” 20 Glasser sees the wedding feast motif as central to the story of Christ’s mission and as connected with the apocalyptic event referred to as the marriage supper of the Lamb. The wedding feast is most closely connected to the Lord’s table 18 Arthur F. Glasser and Charles Edward van Engen, Announcing the Kingdom : The Story of God's Mission in the Bible (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Academic, 2003), 176. 19 Robert L. Gallagher and Paul Hertig, Landmark Essays in Mission and World Christianity (Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 2009), 14. 20 Glasser and Engen, Announcing the Kingdom : The Story of God's Mission in the Bible, 192. From Eden to Eschaton: The Divine Mission of Restoring Lost Community Page 9 and the associated work of Christ on the cross to provide the cleansing which make us ‘fit’ to enjoy the future dream of God. In considering the aspirations and actions of God in accomplishing his dream, there is no greater epicenter than Christ’s work on the cross and the commemorative ‘meal’ instituted in remembrance of this work in the Lord’s table. The Lord’s table, then, becomes the montage for all divine missional activity as well as a foreshadow of its ultimate end, for in the Lord’s table we have instituted both the meal symbolizing how God intends to actualize his dream as well as a picture of the dream in its finality! In Mark 14:22-26, we read “While they were eating, Jesus took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and gave it to his disciples, saying, “Take it; this is my body.” 23 Then he took a cup, and when he had given thanks, he gave it to them, and they all drank from it. 24 “This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many,” he said to them. 25 “Truly I tell you, I will not drink again from the fruit of the vine until that day when I drink it new in the kingdom of God.” 26 When they had sung a hymn, they went out to the Mount of Olives.” The bread and cup are clearly given new meaning, connecting the familiar sacrifice of the Passover Lamb customary in the feast of Unleavened Bread (Mk 14:1), and the new work of Christ as the Lamb of God who was slain (Rev. 5:6;12). The cup, now representing the blood of the covenant, and the bread, now representing Christ’s body, become both the means by which we are made righteous and acceptable in God’s site as well as the food of the commemorative meal that foreshadows the wedding feast of the Lamb. This profound truth is reinforced by Christ himself in v. 25 where he pledges to refrain from drinking the fruit of the vine until it can be drunk ‘new’ in the kingdom of God. This profound pledge indicates something of both the uniqueness and centrality of the meals’ initial meaning and purpose (his death on the cross) as well as the fulfillment of that work after the eradication of all God’s enemies in the kingdom to come. The exegetical work of connecting an event like the Lord’s table in Mark 14 as both From Eden to Eschaton: The Divine Mission of Restoring Lost Community Page 10 literal as well as an allusion to the feast to come in Revelation 21 is not a novel exegetical move. Such an exegetical maneuver is no more of a leap than Karl Barth’s sophisticated yet well documented connection of the motifs of the suffering servant, the apostolic Church, or the calling of the disciples to their eschatological counterparts elsewhere in Scripture.21 What is most refreshing in connecting Christ’s recreation of the Passover feast with the feast to come at the end of the age is the inclusion of thanksgiving and singing (Mk. 14:22;26). In this montage of the table and Christ’s work on the cross we see further evidence of the centrality of the missional aim of God to draw a community of joy together for celebration symbolized in the feast of all time. The Eschaton Feast in Our Time: Acts 2:42-47 The contemporary missional work of God through the global Church began at Pentecost (Acts 2:1), an event of substantial eschatological note but for the purposes of this treatise, it is the aftermath of this event which helps us understand the missional aspirations of God. After the filling of God’s people with the Holy Spirit (2:1-4) and the massive in-gathering of the Jews from ‘every nation’ (2:5;41), we find an incredible description of the community of God which accurately foreshadows the kind of community God’s aspirations have been set on. “They devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and to fellowship, to the breaking of bread and to prayer. 43 Everyone was filled with awe at the many wonders and signs performed by the apostles. 44 All the believers were together and had everything in common. 45 They sold property and possessions to give to anyone who had need. 46 Every day they continued to meet together in the temple courts. They broke bread in their homes and ate together with glad and sincere hearts, 47 praising God and enjoying the favor of all the people. And the Lord added to their number daily those who were being saved.” (Acts 2:42-47).22 21 22 Gallagher and Hertig, Landmark Essays in Mission and World Christianity, 24-25. The Holy Bible : New International Version, Containing the Old Testament and the New Testament. From Eden to Eschaton: The Divine Mission of Restoring Lost Community Page 11 The presence of the ‘breaking of bread,’ a reference to the Lord’s table, and the practice of sharing meals from house to house here demonstrate the missional integration of feasting. In this context, we see gladness, interdependent community, awe, wonders, signs and praise of God. Simultaneously, we see a daily in-gathering of those ‘being saved.’ This holistic portrayal of mission and community provides a vivid glimpse into the dream of God. Furthermore, this early believing community looked forward in their feasting (both symbolically and in their sharing of meals) to the future eschatological feast Christ promised in the institution of communion. Santos Yao, in Dismantling Social Barriers through Table Fellowship writes, “The breaking of bread was thus a time when the eschatological hopes of the believers were stirred, prompting its celebration in an atmosphere of joy (2:46). The early Christians were fully aware that they were ‘the community of the last time constituted by the saving act of God.’” 23 This eschatological community finds its full expression at the wedding feast of the Lamb but in Acts 2 we see a foreshadowing of that ultimate feast. This is a picture of God’s great dream, the contours of which we see emerging throughout the tapestry of Scripture and specifically at the most important missional inflection points of the narrative of God. Compare Acts 2 to the description of joy and gladness we see on the mountain top feast in Isaiah 25:9, “In that day they will say, “Surely this is our God; we trusted in him, and he saved us. This is the LORD, we trusted in him; let us rejoice and be glad in his salvation.”24 Joy and gladness are at the center of a community that has put their trust in God and as a result have been saved. The eschatological community of Acts 2 demonstrates this joy and gladness in their feasting with the missional result being the ingathering of the nations! The true displacing power of this counter-cultural community is not 23 Robert L. Gallagher and Paul Hertig, Mission in Acts : Ancient Narratives in Contemporary Context, The American Society of Missiology Series ; No. 34 (Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 2004), 33. 24 The Holy Bible : New International Version, Containing the Old Testament and the New Testament. From Eden to Eschaton: The Divine Mission of Restoring Lost Community Page 12 just the fact that it disturbs the status quo as Wilbert Shenk argues,25 but more importantly that such a community is an appearance in our time of an out of place community, an apparition of a world to come. In this appearance of the eschatological people of God we see God at work to establish a kind of relational existence for him and his people, one characterized by joy. Toward Holistic Gospel Proclamation: Application for Ministry Context As an abolitionist, I have worked with government leaders, faith-based communities, academic institutions and a litany of non-governmental organizations to create sustainable solutions for the evil of the forced prostitution of children. As an evangelist, I have worked to proclaim a holistic gospel message which is based in both personal and global relevance with an emphasis on justice, judgment, and repentance. In integrating the centrality of restoration, community and joy to both my abolitionist and evangelistic communication, I have found not only a Biblically faithful lens through which to bring these two aspects of my work and passion together but also a culturally effective one. While the Biblical motif of feasting points to the just kingdom which dawns at the eschatological wedding feast of the Lamb, this motif also connects well with my primary, postmodern audience in three ways. First, these motifs and themes help postmoderns see themselves in the grand metanarrative of God’s story which has a future point of reference. This inclusion of a metanarrative and historic arch is something postmoderns in the U.S. long for but often do not find in the oversimplification of a gospel dichotomized by Western theology. Second, inclusion of a more integrative message emphasizing the eschaton and social justice provides a rich opportunity to restore what Samuel Escobar refers to as missional memory.26 In conservative evangelical circles, the heroes of evangelism in the history of mission almost always exclude women and men who sought social justice and an integration of activism with 25 26 Gallagher and Hertig, Landmark Essays in Mission and World Christianity, 119. Ibid., 234. From Eden to Eschaton: The Divine Mission of Restoring Lost Community Page 13 gospel proclamation, like Charles Finney. Restoring this integration through my writings and preaching as a ‘justice evangelist’ enables me to draw upon a rich heritage and to provide the fruit of that heritage for those I intersect with in ministry. Third, hope for myself and for my hearers/readers cannot be fully sustained through a message that merely looks backwards to the first work of Christ on the cross but requires a message that looks forward to the dream of God. Standing in the midst of 180 children this fall in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, I looked into the eyes of prepubescent children who had been raped for pay but who are being restored through the work of my non-governmental organizational partners. For ten years, the horrors of the pay-for rape industry has challenged my faith but it is the hope of the certitude of God’s coming dream that enables me to have joy and to offer the same with integrity to my audiences as well. Conclusion It is the actions of God which that reveals his aspirations for the world he has created. What we see revealed in these actions and in the missional inflection points of Scripture is that God is ultimately after a kind of relational existence for him and his people, one characterized by joy and celebration. We see these aspirations fulfilled ultimately in the wedding feast of the Lamb and in the in-gathering of the nations-events portrayed for us in a litany of foreshadowing events throughout the first and second testaments. The exciting reality of the eschatological feast and the coming dream of God gives us hope in the midst of real and enduring evil and pain. More importantly, as N.T. Wright has said, the future God has planned gives us joy because in the coming of Jesus something real has happened, something God invites us into!27 This ‘something God invites us into’ is seen ultimately in the great feast of feasts, the ultimate fulfillment of the historic divine mission throughout time, it is the dream of God. 27 Church RedeemerPrebyterian, "After You Believe," (2010). From Eden to Eschaton: The Divine Mission of Restoring Lost Community Page 14 Sources Cited Gallagher, Robert L. "The Hebraic Covenant as a Model for Contextualizatoin." 21. Wheaton, IL: Wheaton College Graduate School, Unknown. Gallagher, Robert L., and Paul Hertig. Landmark Essays in Mission and World Christianity. Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 2009. Gallagher, Robert L., and Paul Hertig. Mission in Acts : Ancient Narratives in Contemporary Context, The American Society of Missiology Series ; No. 34. Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 2004. Glasser, Arthur F., and Charles Edward van Engen. Announcing the Kingdom : The Story of God's Mission in the Bible. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Academic, 2003. The Holy Bible : New International Version, Containing the Old Testament and the New Testament. Textbook ed. ed. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan Bible Publishers, 1984. Jacobs, Louis. The Book of Jewish Practices. Springfield, NJ: Berhman House, 1987. Kaiser, Walter C. Mission in the Old Testament : Israel as a Light to the Nations. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Books, 2000. Piper, John. Let the Nations Be Glad! : The Supremacy of God in Missions. 3rd ed. rev. and expanded. ed. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2010. RedeemerPrebyterian, Church. "After You Believe." 2010. From Eden to Eschaton: The Divine Mission of Restoring Lost Community Page 15