Appendix 2: Stakeholder Interview Report

advertisement

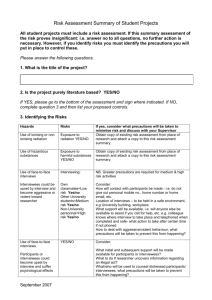

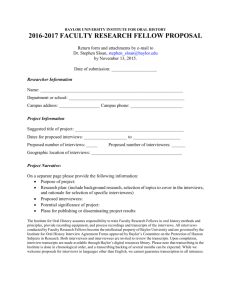

Appendix 2: Stakeholder Interview Report 1.0 INTRODUCTION Twelve interviews were undertaken with key industry stakeholders in order to provide over-arching context on the development of the design industry since 2008. Interviewees were drawn from a range of organisations such as industry associations, universities, and private industry to provide a variety of viewpoints. Interviewees are shown in the table below: Name Title Organisation James Harper President Victoria Branch Design Institute of Australia Simon Goodrich President Australian Interactive Media Industry Association Jim Antonopoulos Vivienne Filling1 Victoria Council President AGDA National Manager, Business Advisory Services Australian Industry Group Herman Mott and Russell King Business Advisers Enterprise Connect Roger Simpson Founder & Director Design Synergy Pty Ltd Brad Dunstan Dr Robert Treseder Greg Branson CEO Director VCAMM Australian Design Academy (ADA) Professor Ken Friedman Dean, School of Design Swinburne University Adjunct Research Fellow President Icograda (20092011) Director Spatial Info Architecture Lab Swinburne University Kristin McCourtie Manager agideas Emily Lai Manager, Colour and Materials Design Ford Australasia Pacific & Africa Russell Kennedy Professor Mark Burry 1 Chair, Advisory Board, ADA RMIT Anne Younger responded to Wallis indicating that Vivienne Filling now oversees the AI Group activities relevant to this research. Wallis met with Ms Filling, along with Herman Mott and Russell King, Business Advisers from Enterprise Connect. 2.0 DEMAND FOR DESIGN SERVICES 2.1 OVERALL DEMAND FOR DESIGN Interviewees who were able to comment on the demand for design services reported that conditions had been challenging for many sections of the industry since 2008. A range of estimates were offered on the overall demand for design. These tended to be ‘steady since 2008’, or, if anything, a slight decline. A few interviewees remarked that the flat demand experienced by the design industry was similar to that felt across the broader economy. Some respondents with links to the manufacturing sector observed that the high Australian dollar was of greater concern to industry than the issues associated with the GFC. While the challenging economic conditions may not have led to a mass reduction in the design work required by industry, some respondents spoke of significant changes to the way in which designers were being engaged. Companies using design have become more cautious about doing so, and are driving a much harder bargain on cost, according to some interviewees. As a result, cost has become a more prominent determiner in awarding work, and design firms are expected to do ‘more with less’. Some manufacturing firms are reported to be lengthening their product life-cycles in response to the leaner economic conditions. For example, this may mean releasing a new version of a product every few years, whereas it may previously have been updated yearly. This is thought to have affected the industrial design sector. 2.2 DIFFERENCES AMONG SECTORS According to interviewees, the challenging economic conditions have been affecting the various design sectors in different ways. According to some, visual communication (viscom) and marketing-related design activities have grown relatively more strongly since 2008. The changes in technology during this period have also had an influence. For example, the increasing importance of the internet and mobile devices has meant strong demand for designers engaged in these areas. Industrial design, by contrast, has been an area of limited, or isolated, growth opportunities. One interviewee remarked that physical sector design activities, for example architecture and interior design, tend to move in parallel with the overall economy. Hence these areas have seen subdued demand, especially in the states not associated with the mining boom. 3.0 COMPETITIVENESS OF DESIGN SERVICES 3.1 VICTORIAN DESIGN SERVICES Interviewees were generally very enthusiastic about the reputation and competitiveness of Victorian designers. Some interviewees commented on Victoria’s rich heritage of manufacturing, and the world-class design ‘know-how’ that emerged to support this industry. Presently, according to interviewees, Victoria is well-regarded nationally, and is expected to do well. The receipt of various national design awards by Victorians thus comes as no surprise. Victoria is also seen as a state where design has been taken seriously at the state government policy level for some time (although some would argue that further support should be provided). The challenge for Victoria is that other states are being seen as ‘narrowing the gap’ and beginning to make inroads into Victoria’s traditional area of strength in design. It is not seen as the case that Victoria’s offerings are slipping, it is that other states are developing their capabilities. Queensland was identified by a number of interviewees as a state that was improving its design capabilities. A number of factors were identified in explaining the tendency of other states to be ‘catching up’ with Victoria. These included: The increasing tendency for the economy to be ‘borderless’ in terms of states. Larger firms will operate across states, and the workforce is increasingly mobile. This leads to a level of cross-fertilisation of ideas. Improved information technology means that the sharing of ideas has become quicker and easier. Other states, notably Queensland, have taken more of a policy interest in design. One interviewee identified a number of initiatives happening outside Victoria that are positive in terms of better use of design in a transdisciplinary context, these were: The establishment of the Prime Minister’s task force on Manufacturing, which is being advised by Goran Roos, a Professor at the University of Warwick, and Founder of Intellectual Capital Services The work of the QMI Solutions in partnership with QUT The establishment of the Advanced manufacturing Council in South Australia. These initiatives indicate that other states may be moving ahead of Victoria in finding practical ways to integrate universities, designers and industry. 3.2 AUSTRALIAN DESIGN SERVICES Respondents often felt that Australian designers were well-placed to secure international work. Some commented that Australian designers were world-renowned, or that they could ‘compete anywhere’. Some interviewees noted that Australian designers were securing work in emerging markets such as India and China. Australian designers are considered to hold a number of attributes that can make them appealing on a world stage. Interviewees noted the reputation of Australian designers as hard-working, having a hands-on approach to design, and being willing to travel. One interviewee commented that Australians winning work abroad were free from some of the ‘cultural baggage’ that Europeans or Americans might carry in certain countries. Despite the international competitiveness of individual Australian designers, and even some particular design firms, interviewees did not tend to have a high view of the competitiveness of the Australian design industry in general. In this area, it is felt that we still lag behind the US and certain European nations. There were a number of reasons put forward for this. One such reason surrounded the scale of the Australian market. When competing overseas, Australian design firms are not generally able to boast of the massive international portfolios that major American and European firms can. One interviewee outlined a second, and more ingrained, impediment to Australia’s international competitiveness. This interviewee felt that Australia’s isolation had historically fostered an ‘it’ll do’ design culture, and that this needs to be overcome in order to be more globally competitive. A number of interviewees provided example of design-using firms that are successfully competing internationally (generally, these were in manufacturing / industrial design areas). These international successes had a number of common elements. They involved the application of design to develop genuinely world-leading products. These products were also designed for specific niche markets, rather than having mass-market appeal. This approach to design and manufacturing was seen by such interviewees as the only way forward for Australia. The ‘race to the bottom’ associated with competition by price was not seen as a sustainable long-term strategy. The question of Australia’s geographic isolation was sometimes identified during discussions about competitiveness. However, this was seen as a diminishing issue. The continued development of more sophisticated communication technology means that the sharing of information is becoming progressively easier. While ‘time on the ground’ in other countries was still identified as critical for those wishing to compete internationally, a variety of more cost-effective and strategic approaches (such as being involved in a consortium) were identified. Some interviewees saw Australia as well positioned in relation to the Asia–Pacific region. Australians are more used to operating in countries such as China, Thailand and Vietnam than their European or American counterparts. Although these countries are advancing their manufacturing base, they are still relatively less sophisticated in terms of design. Hence international companies have the chance to use Australia as a design base. 3.3 DEVELOPMENTS IN DESIGN Participants in the research were asked about developments in design, such as the use of new materials, stemming from advances in nanotechnology, biotechnology or other research areas. There appeared to be little happening in this direction. Generally these advances are likely to come out of university research departments or bodies such as the CSIRO. Working designers do not have the connections or integraton with such places in order to incorporate such advance into everyday designs. The demise of nanoVictoria was lamented by those who had been aware of its work. 4.0 CLIMATE FOR DESIGN IN VICTORIA AND AUSTRALIA 4.1 PUBLIC PERCEPTION OF DESIGN A number of interviewees noted that design is enjoying a more prominent place in public consciousness. People are increasingly becoming aware of the design of products, programs and spaces that they use. One interviewee captured this shift, noting how in the past, someone might have commented ‘this chair is uncomfortable’. Nowadays, the same person is much more likely to note that the chair is ‘poorly designed’. 4.2 INDUSTRY ENGAGEMENT WITH DESIGN The relationship between design and industry was explored more fulsomely in interviews, and the emerging findings are more complex and nuanced. The increase in public awareness of design has been mirrored to an extent by increases in the awareness of design across some areas of industry. ‘Design thinking’ has been adopted by some firms in an attempt to harness the creativity and problemsolving associated with the discipline of design. While this is a good start, some interviewees note that this approach does not go far enough. They argue that issues facing businesses would best be solved by designers, rather than people trying to emulate designers’ thought processes. Most interviewees noted little widespread development in the ways in which SMEs are using design since 2008. It was felt that, at a practical/operational level, few SMEs are taking design into account. An area where some interviewees did note developments was the increasing use of design by SMEs as a source of differentiation. Such use of design might, for example, incorporate a firm-wide integrated re-design of branding, communications and office layout. An interviewee noted that not-for-profit organisations, in particular, had been making increased use of this type of design since 2008. One interviewee expressed concerned with an increasing use of these more ‘shallow’ applications of design. This interviewee felt that an increased focus on design activities aimed at styling products/services was occurring at the expense of design activities that would provide greater value to end users of products/services. The Victorian manufacturing sector’s approach to the use of design has tended to be quite unsophisticated, according to one interviewee who has had a close involvement with the sector. Firms that have tried to use design as part of their innovation processes have sometimes been ‘side tracked’ by the development of the technology, and not properly researched the feasibility or potential demand for new products. As a result, many of such firms have developed an aversion to using design, due to previous poor experiences. The level of integration between firms’ design function and overall activities continues to be an area of interest in the literature. There was some variation between interviewees in their assessment of the extent to which this has been occurring since 2008. Some interviewees felt that design had taken a more integrated place within businesses activities, especially in the area of branding and marketing. A smaller number pointed to the challenging economic climate as a driver behind the use of design occurring in a more fragmented and ad-hoc manner. 4.3 DESIGN EDUCATION Most interviewees felt that Victoria is producing good quality graduates across the design disciplines. Predictably, assessments of graduates’ ‘work readiness’ varied between the respondents. Those interviewees who felt that graduates were adequately ‘workready’ pointed to increases in work experience components of various courses, or initiatives like Swinburne University’s Design Factory, that provides students with real exposure to industry during the course of their studies. Respondents who felt that graduates were not generally work-ready listed concerns with graduates such as a lack of commercial understanding regarding time and budgets, or a lack of professionalism in terms of communication and time-management skills. As was found in previous research, some interviewees did express concerns about design education. It was felt, for example, that design students are too readily allowed to use CAD, and lacked conceptual skills, or the ability to sketch a design and “think with a pencil”. Lack of attention within courses to the practical aspects of real world design, such as the sourcing and costs of materials, was also mentioned. One particular area where interviewees identified a mismatch between graduates’ skills and market requirements was in the area of SMEs. The nature of SMEs demand that new recruits need to be particularly flexible, applying multi-faceted skills to situations, and adopting a strong problem-solving approach. Some interviewees felt that further equipping of design students with such skills would be highly beneficial. The quantity of design graduates was not explored as frequently with interviewees as the question of graduate quality. However, one respondent in particular outlined some of the concerns arising from what they considered to be an oversupply of design graduates (across all design disciplines). This interviewee felt that an oversupply of graduates meant that many were not able to secure quality roles that provide critical early-career development. As a result, the ‘bottom end’ of the design market tends to have a lot of sole proprietors, sometimes competing on price alone, who may not be producing a product that is edifying to reputation of the industry overall. A small number of respondents commented that they would like to see a greater focus on ‘thinking skills’, or skills around researching and developing ideas, within design education. These respondents felt that there was currently too great a focus on training students in the use of various technologies. It was remarked that such technologies will inevitably change and develop, whereas the teaching of problem solving and idea development will provide students with the framework to apply whatever technologies are available to them in order to solve problems. The emergence of ‘trans-disciplinary’ approaches within design education was identified as a positive by a number of interviewees. The Swinburne Design Factory was the most frequently-cited example of this approach. The lack of experience of design graduates from traditional courses in working effectively with other disciplines (e.g. engineering, architecture, marketing) was seen as a weakness in design generally. 4.4 COLLABORATION AND MENTORING Big problems require solutions that draw from a wide range of design disciplines, technological areas, and understandings of the ways in which people and systems interact. Various interviewees pointed out that collaboration therefore becomes a key component in solving complex issues. Many of the respondents were positive in their assessment of the level of collaboration among the stakeholders in the design area. Some felt that an increase in the willingness to collaborate had been one of the main changes in the design landscape since 2008. One interviewee observed: ‘Times are changing. There’s a real convergence between the design industry, business and the education. I think everybody wants to work closer together’. Another interviewee commented that collaboration among businesses was becoming easier, whereas this had been one of the most difficult areas in the past. This interviewee observed that the troubling economic times may even have been a catalyst in this regard; up until 2008 ‘everybody had been busy making money’, so there was little perceived need amongst businesses for collaborative efforts. A number of interviewees were more tempered in their assessment of collaboration, noting that collaboration was still an emerging phenomenon, and was still very much based on individual/personal contacts. The use of mentoring was widely acknowledged among interviewees as a helpful strategy to encourage more effective use of design among companies. A number of interviewees had experience with a variety of programs that incorporated mentoring, either with the explicit or implicit aim of better integrating design within firms. These included the Design Integration Project, and the Business Advisers and ‘Researchers in Business’ programs delivered through Enterprise Connect. Interviewees who had been involved with such programs were enthusiastic about their potential to radically transform the operations of SMEs that participated in the programs. 4.5 THE ROLE OF GOVERNMENTS Discussions about collaboration and mentoring often led to consideration of the role of governments in facilitating or encouraging such collaboration. Respondents generally recognised that the government had a key role to play in providing an environment conducive to collaboration. Governments were seen to have a number of levers available to them such as incentivising collaboration, providing the role of ‘trusted intermediary’ (either directly, or by funding arm’s-length bodies to undertake such roles) or through procurement policies. The use of arm’s length bodies were seen by some interviewees as more advantageous than direct government involvement, due to a greater perceived resilience to electoral cycles. The demise of Design Victoria inevitably arose in discussions with some interviewees. Generally the view appeared to be that Design Vic had mainly acted in the role of publicist and advocate for design, rather than having been an effective catalyst for more effective use of design. However, its activities in facilitating the mentoring of smaller companies to link up to design consultancies were seen as valuable. At the time of the interviews, participants were waiting to see what the new government’s attitude and policies were going to be. The axing of Design Vic with no new policies was seen as having left a vacuum. Government cutbacks in expenditure were also seen as likely to impact the design sector. One interviewee produced a guide to government publications produced by the Treasury, which contained no illustrations or graphic material (and recommended the same) as evidence that the government’s restraints were going to have a strong impact on the Viscom sector in Victoria. The issue of a national design policy was discussed in most of the interviews. Most interviewees were positive toward the idea of a national policy, although there was no clear consensus on the best way to approach this. Some respondents urged that any national policy needed to take account of Australia’s, and the States’ unique contexts; it was not simply a matter of transplanting a successful policy from another country. One respondent, who was cooler toward the notion of a national policy, pointed out that there was a danger in people thinking that the ‘job was done’ once any national policy had been implemented. Interviewees were asked about the work of the Australian Design Alliance (ADA). All of the interviewees were aware of the ADA, and some had been involved to a greater or lesser extent. The consensus was that progress had been slow in regard to lobbying for a national policy on design. A few of the respondents felt that the ADA may be too broad in its constituency to present a clear and compelling voice. Some of the respondents voiced an opinion on the current Victorian government’s approach to design. Of these, a few felt that the current approach was ‘too timid’ or that risk-aversion was leading to the government being unable to make decisions. Following this line of argument, one stakeholder commented that they would like to see the government identify specific initiatives/areas of promise, and then take a risk to ‘back’ these initiatives/areas. 5.0 CONSIDERATIONS FOR THE RESEACH 5.1 FURTHER CONSIDERATIONS One of the chief developments since 2008 has been a greater understanding of the need for collaboration between stakeholders involved with design, and the increased use of mentoring to develop the design capabilities of SMEs. Accordingly, we have drafted questions to be included in the design consultancy, and general business surveys to gauge such activities. The contextual information gained through this stage of the research will be particularly useful in ‘unpacking’ the results that emerge from the surveys.