includes Tables S2 and S3

advertisement

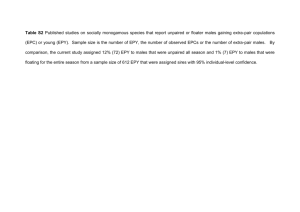

Electronic supplementary material for Offspring fitness varies with parental extra-pair status in song sparrows, Melospiza melodia Rebecca J. Sardell, Peter Arcese and Jane M. Reid 1) Diagram of fitness measures and relationships mixed paternity brood 2: mixed paternity brood 1: extra-pair male focal polyandrous female ♂ socially paired male ♀ EPY ♀A ♀A ♀F ♀G ♂B ♂E ♂ ♂ WPY ♂C ♀D ♂C ♀D + ♂E ♀H ♂I ♂J i) survival to recruitment ♀F ♂I ♂J ii) hatched offspring ♀♂ ♀ ♀♂♀ ♀ ♀ iii) recruited offspring 1 Figure S1 Variation in fitness of a focal polyandrous female’s grandoffspring (hatchlings FJ) was analysed with respect to their parents’ extra-pair status (individuals A-E). Fitness was measured as: i) survival to recruitment, ii) lifetime probability of having ≥1 hatched genetic offspring and iii) lifetime probability of having ≥1 recruited genetic offspring. Only hatchlings whose mother and father were both from mixed paternity broods (e.g. hatchlings I and J from parents D and E) were included. Dashed and solid lines represent an individual’s survival and reproductive success. Grey lines represent instances where individuals did not survive or reproduce. 2 2) Sample size Table S1 Sample sizes for analyses comparing i) survival to recruitment and ii) the probability of having ≥1 hatched or recruited offspring between hatchlings with mothers and social or genetic fathers that were themselves extra-pair young (EPY) or within-pair young (WPY). mother extra-pair status i) ii) EPY WPY total EPY WPY total social father extra-pair status EPY 53 83 136 32 44 76 grand total WPY 16 48 64 0 40 40 200 116 genetic father extra-pair status EPY 56 82 138 28 47 75 grand total WPY 14 67 81 4 53 57 219 132 3 3) Supplementary analyses of hatchling extra-pair status and sex Chi-squared tests were used to test whether EPY or WPY parents produced more male than female hatchlings, or EPY than WPY, thereby potentially confounding analyses of variation in hatchling fitness components with respect to parental extra-pair status (tables S2 and S3). The proportion of hatchlings that were themselves EPY was similar across the three parental extra-pair status groups (two WPY parents, one EPY parent, two EPY parents) in three of four datasets. In the fourth dataset (describing hatchling recruitment with respect to social father extra-pair status) the proportion of EPY hatchlings was smaller when both parents were WPY, but not significantly so (table S2). The proportion of hatchlings that were EPY was similar in seven of eight comparisons of EPY and WPY mothers and fathers (electronic supplementary material, table S3). In the eighth comparison (for the dataset describing the probability of having ≥1 offspring given genetic father status) more hatchlings were EPY for WPY fathers than for EPY fathers, but not significantly so given multiple comparisons (table S3). The proportion of male hatchlings was similar in all three parental extra-pair status groups, and between EPY and WPY mothers and fathers, for all four datasets (tables S2 & S3). 4 Table S2 The number (n) and percentage (%) of hatchlings that were extra-pair young (%EPY) or males (%male) and had two withinpair young (WPY) parents (WP/WP), one EPY parent and one WPY parent (WP/EP) and two EPY parents (EP/EP). Bonferronicorrected p-values (p) and chi-squared test statistics (χ2) indicate whether the proportion of hatchlings that were EPY or male varied significantly with their parent’s extra-pair status. Data are presented for all four datasets analysed: i) and ii) probability of survival to recruitment with social and genetic father extra-pair status respectively; iii) and iv) probability of having ≥1 offspring with social and genetic father extra-pair status respectively. dataset Offspring extra-pair status (% EPY) Offspring sex (% male) WP/WP WP/EP EP/EP WP/WP WP/EP EP/EP parents parents parents parents parents parents total n % n % n % χ2 p n % n % n % χ2 p n i) 3/48 6% 24/99 24% 11/53 21% 6.94 0.12 21/48 44 56/99 57 31/53 59 2.72 1.00 200 ii) 22/67 33% 21/96 22% 14/56 25% 2.50 1.00 30/67 45 57/96 59 32/56 57 3.63 0.64 219 iii) 3/40 8% 6/44 14% 8/32 25% 4.41 0.44 18/40 45 24/44 55 18/32 56 1.13 1.00 116 iv) 16/53 30% 13/51 25% 4/28 14% 2.48 1.00 23/53 43 30/51 59 17/28 61 3.33 0.76 132 5 Table S3 The number (n) and percentage (%) of hatchlings that were extra-pair young (%EPY) or males (%male) with extra-pair young (EPY) or within-pair young (WPY) mothers and fathers. Bonferroni-corrected p-values (p) and chi-squared test statistics (χ2) indicate whether the proportion of hatchlings that were EPY or male differed significantly between EPY and WPY mothers or fathers. Data are presented for all four datasets analysed: i) and ii) probability of survival to recruitment with social and genetic father extra-pair status respectively; iii) and iv) probability of having ≥1 hatched or recruited offspring with social and genetic father extra-pair status respectively. dataset Offspring extra-pair status (% EPY) EPY mother Offspring sex (% male) WPY mother EPY father WPY father EPY mother total WPY mother EPY father WPY father n % n % χ2 p n % n % χ2 p n % n % χ2 p n % n % χ2 p n i) 17/69 25 21/131 16 1.65 0.80 29/136 21 9/64 14 1.06 1.00 39/69 57 69/131 53 0.14 1.00 79/136 58 29/64 45 2.37 0.48 200 ii) 18/70 26 39/149 26 0.00 1.00 31/138 22 26/81 32 1.99 0.64 40/70 57 79/149 53 0.18 1.00 81/138 59 38/81 47 2.40 0.48 219 iii) 8/32 25 9/84 11 2.73 0.40 14/76 18 3/40 8 1.70 0.76 18/32 56 42/84 50 0.16 1.00 42/76 55 18/40 45 0.73 1.00 116 iv) 8/32 25 25/100 25 1.34 1.00 13/75 17 20/57 35 4.54 0.12 19/32 59 51/100 51 0.39 1.00 45/75 60 25/57 44 2.77 0.40 132 6