Marotti, "The Manuscript Transmission of Poetry"

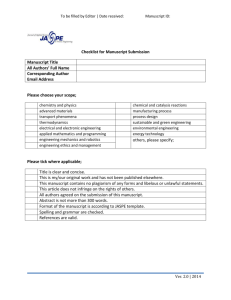

advertisement