Comparative research on mother tongue education: What is wrong

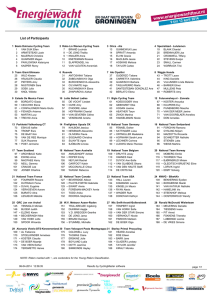

advertisement

MTE in different meaning creating contexts (Piet-Hein van de Ven) Handout, conference 'Towards a common European framework of reference for languages of school education?' Kraków, Poland April 27-29, 2006 1 Looking into the classroom: Five lessons writing (based on observations, teachers’ diaries, interviews; Van de Ven, 1994) - The Hungarian lesson: Pupils 11 years of age. Fictional text. Evaluation by teacher: focus on landscape description (model). Product oriented writing, modelling approach. Teaching and learning: transmission of knowledge (Nystrand et al., 1997)??? - The Swedish lesson: Pupils 11 years of age. Creative writing, fictional text. Topical questions. Texts read aloud. The teacher gives positive feed back. Focus on contribution to role play. Teaching and learning: transformation of understandings Nystrand et al., 1997)??? - The German lesson: Pupils 11 years of age. Finishing a fairy tale. Writing in groups. Topical questions. Evaluation by teacher emphasising characteristics of fairy tales. Modelling approach, product oriented. Teaching and learning: transmission of knowledge??? - The Dutch lesson: Students aged 17. Argumentative text. Anecdotal introduction, stylistic devices. Evaluation by teacher, preparation for examination. Product oriented. Transmission of knowledge??? - The Norwegian lesson: Students aged 18. Text about ‘cross roads’. Choice between six different kinds of texts. Teacher emphasises the text charactistics. Evaluation by teacher, preparation for examination. Transformation of understandings???. Language portfolio: what can/want/should each pupil/student formulate in the own language portfolio? What indicators are needed in order to understand their different abilities inb writing? Translation: ‘opstel’ (Dutch) is and isn’t ‘stil (Norway), is and isn’t ‘essay (English), etc. Recognition: Dutch student teachers identified Dutch lesson. But found this difficult to explain. 2 Making the familiar strange Framework of studying these five lessons: IMEN research: making familiar strange (www.lu.hio.no/imen) by making the strange familiar. Starting point: Personal experience: Grammar (Germany) isn’t grammatica (Netherlands). Germany-Netherlands: two different cultures of mother tongue education. International research co-operation. Conceptual problem: Dutch, Swedish, English, etc. is and isn’t mother tongue, standard language, first language, national language. IMEN chose traditional concept Mother Tongue Education (MTE). IMEN research 1981- nowadays. Comparative research on MTE. Document analysis, classroom observation, teachers’ diaries, and historical approach. National-cultural conceptions of MTE: Grammar isn’t grammar; literature isn’t literature, national cultural heritage sometimes is European cultural heritage. Functional language education: four different interpretations - Field structures of MTE show more integrated and more collection codes (classification and framing; Bernstein 1977). Time and again big gaps appear between rhetoric (what ought to be done, what should be done) and practice (what observably is done). Paradigmatic debates. MTE a polyparadigmatic field. Paradigms: community of scholars (and communities of teachers) (Kuhn, 1962), sharing agreement on topics, activities and legitimation of mte (Reid, 1984), a paradigm being a ‘meaning creating context’(Englund, 1996). ‘Literature’ in an literary-grammatical paradigm isn’t ‘literature’ in a communicative paradigm, etc. Several European countries show paradigmatic change in 60s/70s: towards communicative mte (Herrlitz et al., 1984;Delnoy, Herrlitz & Kroon, 1995). Paradigmatic change more prominent in rhetoric than in practice. Concept of communication: different meanings, practices. Translation problems: Didactics (English) e.g. is not similar to didaktiek (Dutch), Didaktik (German, Scandinavian), la didactique (French). There are concepts that appear to be hardly translatable, like ‘Bildung’. In Sum: MTE appeared to be ‘a social construction’. There are different conceptions of language, grammar, literature, etc based upon paradigmatic choices (mainly in rhetoric) ànd national-cultural traditions (practice). The field structure of the school subject appeared to differ too. Constituents like literature, writing, oral communication, grammar, new media, reading, are differently mutually connected (or not). There are differences in the patterns of dominance between these constituents, literature being dominant in Germany, language abilities in the Netherlands. Not all countries have the same constituents, although literature, grammar, reading and writing appear to be the ‘hard core’ of the subject. 3 Cultural differences in other fields of language and communication Empirics: Elbow (1991): differences between German and British Academic discourse Herrlitz (1993): directedness in international communication Van Mulken & Van den Brandt (2002), Dutch, Spanish and French dating advertisements. Hendriks et al. (2005): differences in style, culture and argumentation. Theories: Brown, P. & Levinson, S.C. (1987). Politeness. Gudykunst, W.B. & Ting-Toomy, S. , Chua, E. (Eds.) (1988). Culture and communication Hofstede, G, (2001), Culture’s consequences. Schwartz (1994). Human values Etc. 4 Common European Framework? Trend of homogenisation reflected in the development of national curricula, mostly in the context of lingual and cultural diversity versus homogeneity. National standard language education as a homogenising tendency on the national level, confronted with multilingualism by by immigrant languages. And existing diversity in local and regional language variety. Homogenising tendency in the European Common Market with English as new lingua Franca. With problems of translation of core concepts (like Bildung). Homogenising tendencies on the national level (education in the national literature - national canon), a competing homogeneity in the perspective of teaching European literature. National or European standards (the canon) and world-wide globalisation of culture, diversity caused by the attention for youth culture, youth literature, new genres and (new) media. IMEN: MTE is a social construction. Different meaning creating contexts: national-cultural educational traditions, different paradigms, rhetorics-practices, international communication, Thus: heterogeneity between and within national traditions of mte. Making the familiar strange: learning from diversity. Common European Framework: accepting cultural differences between and within national cultures? In any case: political and epistemological choices. References: Bernstein, B. (1971), On the classification and framing of educational knowledge. In: Young, M. (Ed.) (1971), Knowledge and control; new directions for the sociology of education. London: CollierMacMillan,pp. 47-69. Brown, P. & Levinson, S.C. (1987). Politeness. Some universals in language usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Delnoy, R., W. Herrlitz & S. Kroon (Eds.) (1995), European Education in Mother Tongue. A Second Survey of Standard Language Teaching in Eight European Countries. Studies in Mother Tongue Education 6. Nijmegen: IMEN. Elbow, P. (1991), Reflections on academic discourse: How it relates to freshmen and colleagues. College English 53, 2, 135-155. Englund, T. (1996), The public and the text. Journal of Curriculum Studies 28, 1, 1-35. Gudykunst, W.B. & Ting-Toomy, S. , Chua, E. (Eds.) (1988). Culture and interpersonal communication. Newbury Park: Sage. Hendriks, B., Starren, M., Hoeken, H., Van den Brandt, C., Nederstigt, U. & Le Pair, R. (2005). Stijl, cultuur en overtuigingskracht. De invloed van culturele stijlverschillen opo de overtuigingskracht van een fondswervingsbrief. Tijdschrift voor taalbeheersing 27 (3), 230-244. Herrlitz, w. (1992). Text processing in intercultural business communication. In: Pander Maat, H. & Steehouders, M. (Ed.s). (1992). Studies of functional text quality. Amsterdam, Atlanta: Rodopi. Pp. 45-56. Herrlitz, W., A. Kamer, S. Kroon, H. Peterse & J. Sturm (Eds.) (1984), Mother tongue education in Europe. A survey of standard language teaching in nine European countries. Studies in Mother Tongue Education 1. Enschede: SLO. Hofstede, G, (2001), Culture’s consequences. Comparing values, behaviours, institutions, and organizations across nations. Thousand Oaks etc. Sage Kuhn, T. (1962), De structuur van wetenschappelijke revoluties. Amsterdam, Meppel: Boom 1972 (The structure of Scientific Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.1962, met het post scriptum uit 1969). Nystrand, M., Gamoran, A., Kachur, R., Prendergast, C. (1997). Opening Dialogue. Understanding the Dynamics of Language and Learning in the English Classroom. New York, London: Teachers College, Columbia University Reid, W. (1984), Curricular topics as institutional categories: implications for theory and research in the history and sociology of school subjects. In: Goodson, I. & S.J. Ball (Eds.) (1984), Defining the curriculum. Histories and Ethnographies. Lewes: The Falmer Press. Schwartz, S. (1994). Are there universal aspects in the structure and contents of human values? Journal of Social issues 50 (4), pp. 19-45 Van de Ven, P.H. (1994a), Schreiben: einige Beispiele aus IMEN-Fallstudien. Osnabrücker Beiträge zur Sprachtheorie 48, Mai 1994, 137-150. Van Mulken, M. & Van den Brandt, C. (2002). Man zoekt ditto vrouw – Verkenning van de mogelijkheden van crosscultureel onderzoek naar aanleiding van een corpus van Nederlandse, Franse en Spaanse contactadvertenties. In: Van den Brandt, C. & Van Mulken, M.(Red.). Bedrijfscommunicatie II. Een bundel voor Dick Springorum bij gelegenheid van zijn afscheid. Nijmegen: NUP., p. 243-264. Nijmegen, April 2006 Piet-Hein van de Ven Radboud University Nijmegen, The Netherlands P.vandeVen@ils.ru.nl Piethein.vandeven@han.nl