Katrina Wicker - Cindycupp.com

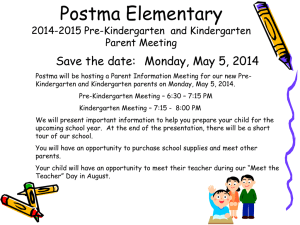

advertisement