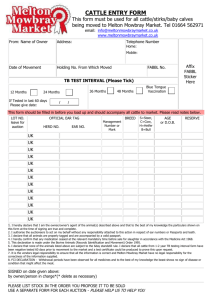

General Production Information

advertisement

Livestock Profile for Beef Cattle Production (Pasture and Range) in Montana General Production Information Montana (Jan 2005) ranked 12th in total number of all cattle and calves (2.35 million), accounting for 2.5% of U.S. inventory. Montana beef cows rank 7th (1.432 million) accounting for 4.3% of U.S. inventory. All cattle and calves both on farms and ranches: The average price per 100 pounds was $106 for calves and $82.20 for beef cattle during the 2003 season. Cash receipts (2003) from the sale of cattle and calves totaled $954,933,000. In addition, there was $9,535,000 value in home consumption of beef with the total gross income from cattle and calves totaling $964,468,000. Montana ranked 30th in the nation in terms of total cash receipts from livestock (2003), the last year for which this report is available. Bulls over 500 (2004): 90,000 Steers over 500 lb (2004): 200,000 Beef replacement heifers (2004): 420,000 Other heifers over 500 lb (2004): 142,000 Calves under 500 lb (2004): 50,000 Calves born (2004): 1.52 million Cattle and calves slaughtered (2004): 18,600 (Includes slaughter in federally inspected and other slaughter plants but excludes animals slaughtered on farms.) Beef cow operations (2004): 11,500 Cultural Practices The beef cattle industry in Montana represented 51% of the total gross agriculture receipts for 2003. In 2003, over $954 million was received from the sales of cattle and calves in the state. The majority of the beef cattle industry is in southwest Montana and east of the mountains. There are cow/calf operations on native grassland and cow/calf operations on improved grass pasture. Cow/calf operators generally run their calves with the cow until the calf is weaned. Calving takes place primarily in the late winter and early spring with calves being weaned in the fall of the year. Calves are then sold, fed through the winter and sold or pasture-raised in the spring. BEEF COWS and HEIFERS THAT HAVE CALVED Inventory by counties, January 1, 2004, Montana, USA Last updated May 26, 2004 GLACIER TOOLE LINCOLN HILL LIBERTY SHERIDAN DANIELS VALLEY ROOSEVELT FLATHEAD PONDERA BLAINE PHILLIPS RICHLAND CHOUTEAU TETON LAKE SANDERS MCCONE LEWIS AND CLARK MINERAL DAWSON FERGUS CASCADE PETROLEUM GARFIELD PRAIRIE MISSOULA JUDITH BASIN MEAGHER POWELL WIBAUX ROSEBUD MUSSELSHELL GRANITE GOLDEN VALLEY FALLON WHEATLAND BROADWATER CUSTER TREASURE RAVALLI DEER LODGE YELLOWSTONE SWEET GRASS STILLWATER JEFFERSON GALLATIN SILVER BOW CARTER MADISON BIG HORN BEAVERHEAD POWDER RIVER CARBON PARK <10,000 10,00020,000 20,00030,000 30,00040,000 40,00050,000 >50,000 ----------------------------------------Head on Inventory--------------------------------------- Figure 1. Beef cows and heifers that have calved, inventory by counties, January 1, 2004. Numbers were derived from Montana Agricultural Statistics annual summary report. Leading production counties were Beaverhead County in the Southwest reporting district with 78,000 head, Fergus County in the Central reporting district with 67,000 head, Big Horn County in the South central reporting district and Valley County in the Northeast reporting district with 57,000 head. Insect Pests Insects, ticks and mites can cause direct and indirect losses to the beef industry. Irritation, annoyance, blood loss and insect contamination of meat are direct losses. In addition, insects transmit many bovine diseases. The USDA estimated that insects and mites cause $2.2 billion annual loss to the cattle industry in this country (Mock, 1997). Extension agents from several counties in Montana have indicated that lice, flies, mosquitoes, gnats and ticks are the most prevalent insect pests in their counties. Following are major pests that cause problems and the control methods recommended for pastured cattle: Flies: Flies are the primary insects of concern on pastured cattle. Several types of flies that affect cattle include horn flies, face flies, horse and deer flies, stable flies, black flies, culicoides and mosquitoes. Horn Flies (Haematobia irritans). The horn fly is a small (one-half the size of a house fly) obligate parasite and is the same general color as the stable fly. They have piercing-sucking mouthparts with which they obtain blood from the host. As adults, they spend most of their time on the back of cattle, feeding on blood 30-40 times per day. During cool weather, they congregate about the base of the horn to rest. The females deposit eggs in fresh manure during early spring to late fall. The life cycle consisting of egg, larva, pupae and adult stages can be completed in two weeks during warm weather. The fly overwinters in the pupal form under or near manure pats. Animal Response and Economic Losses If left untreated, horn fly populations will reach several hundred per animal by late July or early August. At this level, cattle will usually bunch, fail to graze properly and expend considerable energy in tail switching, head throwing and stamping in an attempt to dislodge flies. High numbers (over 200) of horn flies may reduce weaning weights, because of reduced cow milk production, yearling weights and cow body condition scores. The degree of loss is associated with quantity and quality of forage available and climate. At elevations of over 6500 feet, horn fly populations may not surpass 200 per animal, and therefore, are non-economic. Management Approaches Cultural There are no cultural methods available to reduce horn fly numbers. Biological There are some predators and pupal parasites that reduce horn fly numbers to some degree but not enough to control them. It would not be practical to rear and release these predators or parasites. Chemical Insecticides used for control of horn flies are administered primarily for self-treatment by the cattle. These would include dust bags, oilers, ear tags impregnated with insecticides and mineral blocks or feed treated with an insecticide. Dust bags and oilers can be either forced use or free choice. Forced use is when cattle must pass through a gate with dust bags or oilers hung in it to obtain water, feed or mineral. Free choice is where cattle have access to dust bags or oilers but don’t have to use them. Ear tags contain an insecticide, which moves to the surface of the tag from ear movement and is then wiped on the haircoat of the animal, where horn flies come into contact with it. When first used, ear tags containing pyrethroid insecticides provided excellent seasonal control. However, within a few years, horn fly resistance to pyrethroids was widespread. After resistance developed, horn fly control recommendations returned to those made prior to the ear tags. Animal health companies then developed ear tags containing phosphate insecticides with no history of resistance, boluses that contained methoprene, a juvenile hormone, and ivermec, a broad spectrum parasiticide and newer, more toxic pyrethroids often with a synergist added to increase toxicity or a mixture of a phosphate and pyrethroid insecticides. None of the newer insecticide ear tags to date have provided either the degree or length of control as the original pyrethroid-only tags. At about 60 days after application, the current ear tags start to decline in efficiency because of a reduction in the amount of insecticide released. Sprays and pour-on insecticides will control horn flies for 2-3 weeks after application and could be used when the ear tags start to decline in efficacy. Using sprays or pour-ons for seasonal control probably is not practical for range cattle because of the difficulty in rounding up cattle for treatment. The stress of handling the cattle might offset treatment gains. Extension entomologists developed a set of recommendations to delay or prevent the development in resistance in horn fly populations to the newer insecticides contained in ear tags. These include: 1) delay tagging animals until horn fly numbers are at an economic level (200+ per animal); 2) rotate insecticides at least yearly, a phosphate with a pyrethroid; 3) provide alternate treatment methods when ear tag efficacy declines; 4) treat only animals in a weight gain mode (i.e., cows with calves and yearlings); 5) remove ear tags at the end of the fly season. Insecticide Suggestions for Horn and Face Flies Insecticide Application Method Application Rate Restrictions and comments Restricted-Use Pesticide: Co-Ral products are not used on animals younger than three months. Coumaphos (Co-Ral ELI) Spray 11.6% ELI 2.5 oz/4 gal water (Co-Ral Fly & Tick Spray) Spray 6.15% EC 2 qt/50 gal water or 5 oz/4 gal water Spray to run-off. Treat no more than six times per year. Do not make applications less than 10 days apart. (Co-Ral Plus) Ear Tag 20% Coumaphos + 20% Diazinon AI Two tags per animal. Beta-Cyfluthrin (CyLence Ultra) Ear Tag 8% Beta-cyfluthrin + 20 % PBO AI Two tags per animal. Not for use on calves less than 3 months old. Cyfluthrin (Cutter Gold) Diazinon Ear tag 10% AI Two tags per animal. (Cutter 1) Ear tag 40% AI Two tags per animal. (OPtimizer) Ear tag 21.4% AI Two tags per animal. Not for use on lactating Insecticide Application Method Application Rate Restrictions and comments animals. No treatment/slaughter interval. (Patriot) Ear tag 40% AI Two tags per animal. Not for use on lactating animals and calves less than three months. (Warrior) Ear tag 40% AI Two tags per animal. No treatment/slaughter interval. (X-Terminator) Ear tag 20% AI Two tags per animal. Not for use on lactating animals. Doramectin (Dectomax) Pour-on 0.5% AI (5mg/ml) Do not treat lactating dairy cows or heifers over 20 months old. 45 day treatment/slaughter interval. Eprinomectin (Eprinex) Pour-on 5 mg/ml AI 1 ml/22 lb body wt No treatment/slaughter interval. Ear tag 36% AI Two tags per animal. Ear tag 8.6% AI Two tags per animal. (Atroban DeLice) Pour-on 1% AI 15 ml(1/2 fl oz)/ 100 lb body wt Do not apply more than once every two weeks. Maximum of 5 oz per animal. (Atroban EC) Spray 11% EC 1 pt/25 gal water Spray to thoroughly wet animal. Do not apply more than once every two weeks. (Atroban Extra) Ear tag 10% Permethrin + 13% PBO Two tags per animal. (Boss) Pour-on 5% AI 3 ml/ 100 lb body wt Maximum of 30 ml per animal. Do not apply more than once every two weeks. (Brute) Pour-on 10% AI 3 ml/100 lb body wt. Do not treat more than once every two weeks. Apply down midline of back over shoulders. No treatment/slaughter interval. Back rubber Dilute 48 ml in 1 gal diesel fuel or oil Ethion (Commando) Fenvalerate (Ectrin) Permethrin Insecticide Application Method Application Rate Restrictions and comments (Ectiban) (Insectiban) Spray 5.7% AI 1 qt/25 gal water Spray to thoroughly wet animal. Do not apply more than once every two weeks. No treatment/slaughter interval. (GardStar) Spray 40% EC 4 oz/25 gal water (High pressure spray) Spray over whole body surface to thoroughly wet animal. Do not apply more than once every two weeks. (Longer residual control.) No treatment/slaughter interval. 4 oz/2.5 gal water (Low pressure spray) Spray midline from face to tail head until wet but do not allow runoff. Do not apply more than once every two weeks. (2-3 weeks residual control) No treatment/slaughter interval. (GardStar Plus) Ear tag 10% AI Two tags per animal. No restrictions. (Permectrin) Pour-on 1% AI 1/2 oz/100 lb body wt Maximum of 5 oz per animal. Do not treat more than once every two weeks. (Permectrin CDS) Pour-on 7.4% Permethrin + 7.4% PBO 1.5 ml/100 lb body wt Maximum of 15 ml per animal. (Permectrin II) Spray 10% AI 1 pt/100 gal water If necessary repeat in 14 days. No treatment/slaughter interval. (Permethrin) Dust bag 0.25% AI dust Do not use in pyrethroid resistant areas. (Synergized DeLice) Pour-on 1% Permethrin + 1% PBO 15 ml(1/2 fl oz)/ 100 lb body wt Maximum of 5 oz per animal. Do not treat more than once every two weeks. (Ultra Boss) Pour-on 5% Permethrin + 5% PBO 3 ml/100 lb body wt Maximum of 30 ml per animal. Do not apply more than once every two weeks. Phosmet (Del-Phos) Spray 11.6% EC 1 gal/50 gal water Apply to point of runoff. Do not treat animals less than three months old, sick or stressed animals. Treatment-slaughter interval 3 days. Insecticide Application Method Application Rate Back rubber 1 gal/50 gal of fuel oil, or other suitable carrier Pirimiphosmethyl (Dominator) Ear tag 20% AI Apply two tags per animal. (Double Barrel) Ear tag 6.8% Lambdacyhalothrin + 14% Pirimiphos methyl Apply two tags per animal. Stirofos (Rabon) Dust bag 3% dust Follow label directions. No treatment/slaughter interval. Spray 24% EC Horn and face fly control only. Back rubber Spray 50% WP 4 lb/75 gal water Apply 0.5 to 1 gal per animal. Mineral additive 1.23% AI Follow label directions. ROL 7.76% AI Premix Follow label directions. Spray 23% Rabon + 5.3% Vapona 1 gal/75 gal water Do not apply to Brahman cattle. Do not treat more than every 10 days. Do not apply to calves less than six months old. Back rubber 1 qt/25 gal of approved back rubber oil (PYthon) Ear tag 10% Zetacypermethrin + 20% PBO (9.5 g) Apply two tags per animal for control up to five months. No treatment/slaughter interval. (PYthon Dust) Dust bag 0.075% Dust Zetacypermethrin + 0.15% PBO No restrictions – apply up to 2 oz/animal as necessary but not more often than every three days. (Ravap) Restrictions and comments Zetacypermethrin Insecticide (PYthon Magnum) Application Method Ear tag Application Rate Restrictions and comments 10% Zetacypermethrin + 20% PBO (15.4 g) Apply only 1 tag per animal. Do not apply to calves less than 3 months old. No treatment/slaughter interval. Face Fly (Musca autumnalis). The face fly resembles the house fly in size and appearance but is considerably different in behavior and life cycle. Like horn flies, face flies deposit eggs in the fresh manure of cattle on rangeland or pasture. The life cycle takes about three weeks to complete. Face flies overwinter as adults in sheltered areas such as attics and siding in houses, barns and sheds. On warm winter days, they may become active and become a pest in the living quarters of an infested house. Although adult flies feed on other large mammals (i.e. horses), the face fly is dependent on cattle for its survival and propagation. The face fly is a persistent feeder around the eyes and nose, where it feeds on mucous and tears. Adults have sponging mouthparts and only the females are parasitic. The feeding injures the tissue around the eyes, which causes tearing and provides an avenue for the entrance of eye pathogens such as Moraxella bovis, one of the causative agents of pinkeye. Management Approaches Biological Considerable research with a nematode that destroys female ovaries and a pupal parasite that killed the pupae was conducted in Nebraska, but neither proved effective enough to be employed for control. Chemical The insecticides recommended for control of horn flies will also control face flies. Dust bags and oilers should be placed so they also treat calves in a cow-calf herd because the face fly is attracted to both cows and calves, unlike horn flies that infest cows primarily until the numbers become very high on cows. The recommendation to rotate insecticides should be followed for face flies because horn flies are always present on cattle, whether or not they have face flies. (For Insecticide Suggestions – see horn flies.) Stable Fly (Stomoxys calcitrans). The stable fly is about the size of a house fly but darker in color with a greenish-yellow sheen, has a checkered abdomen and possesses piercing-sucking mouthparts (proboscis). The abdomen has dark irregular spots. The proboscis (mouthpart) protrudes bayonet-like in front of the head. The life cycle consists of egg, larva, pupae and adult. The life cycle can be completed in 21-24 days during the summer months. Stable flies breed in decaying wet organic matter including spilled feed, manure mixed with wet soil, grass clippings and wet hay in areas where big bales are fed and in racks, bunks or stack yards where hay accumulates on the wet ground. Stable flies feed on blood, usually by attacking the front legs of cattle or horses, although they will feed on other warm-blooded animals as well. Stable flies overwinter as slowly developing larvae in breeding areas below the frost line. As temperatures warm in the spring, they migrate closer to the surface and pupate. The first adults that emerge probably freeze, but eventually enough survive to mate and deposit eggs for the new generation. Animal Response and Economic Losses Stable flies normally are considered pests of confined cattle at dairies or feedlots, but more recently, they have been noted as pests of range cattle as well. They feed primarily on the front legs of cattle and cattle under attack will bunch with each animal attempting to protect its front legs. Losses occur from both bunching, which increases or causes heat stress and from annoyance and use of energy to try to dislodge the flies by tail switching, stamping their feet, and throwing their heads down by their front legs. Range and pasture cattle will bunch downwind by a fence and fight flies in the same manner. Management Approaches Cultural Stable fly control for confined cattle starts with good sanitation, cleaning up spilled feed, fixing leaky waterers, providing good drainage from the pens and building, maintaining good mounds, cleaning pens, scraping behind feed bunk apron and restricting pen size to create better drying conditions. Biological Considerable research has been conducted on biological control of stable flies with parasites. Small wasps (pteromalids) parasitize stable and house fly pupae. Several commercial insectaries have several species of these for sale. Some researchers claim success with inundative releases of these parasites. Research conducted at feedlots and dairies with confined cattle found that they did not provide adequate control at release rates considerably higher than recommended and that they were more expensive than standard control methods. Chemical Stable fly control with insecticides may be achieved with two application methods. One is knockdown spray applied into fly infested areas, which kills flies by spray contact. The other method is the application of residual sprays to fly resting areas or shady surfaces. The mist applications as area sprays may be applied with hydraulic sprayers, aircraft or mist blowers. If the feedlot or dairy has a windbreak around some of it, misting in the trees during the hot part of the day, when flies seek shade, may be more effective than spraying the feedlot pens. Control of stable flies on range or pasture cattle is difficult. In Nebraska studies, cattle had to be sprayed three times per week to keep stable flies at levels that did not impact grazing steer weight gains. Aquatic Biting Flies Black Flies (also called buffalo and turkey gnats) (genus Simulium). Black flies are small (25 mm in length) and dark colored with a ‘humpbacked’ appearance. The females are blood feeders. Some species attack birds, hence the name turkey gnats, but most feed on cattle and horses. Simulium vittatum feed in the ears of horses, cattle and other animals. Eggs are deposited in layers or irregular strings on the surface of objects that are kept moist by water movement or in the water. Larvae can be found attached to stones, branches, grass or other debris in swift-flowing water. They attach to the substrate by means of posterior suckers, which contain hooks. Most species possess mouth brushes, which are used to filter food from water. Animal Response and Economic Losses There are no studies relating numbers of black flies to animal losses. Annoyance of livestock under attack is evident, particularly by those that feed in the ears. Livestock deaths have been reported in a few instances with outbreak numbers and calves have been asphyxiated from inhaling too many of the black flies. Management Approaches Chemical Insecticides used as cattle sprays for other livestock insects may provide some reduction in black fly numbers. Culicoides spp. (biting gnats, punkies, no-see-ums) (family Ceratopogonidae). The Culicoides are very small (1-4 mm long), thus the common name ‘no-see-ums.’ The females have piercing, sucking mouthparts composed of a short piercing proboscis, legs are short and stout and wings are superimposed over the back while at rest. Eggs are usually deposited in masses of 25-300 in water. Margins of streams and lakes, mud holes, tree holes, axils of plants, salt marshes, tide pools, swamps, rice fields and runoff from dairy and feedlot pens are all habitats for the Culicoides. Late instar larvae are eel-like in appearance. In temperate regions, most species overwinter as larvae but a few overwinter in the egg stage. Animal Response and Economic Losses There is no economic loss data in the literature concerning Culicoides except losses because of blue tongue virus. Cows or heifers not previously exposed to blue tongue may have abortions, but the disease is primarily a problem for sheep. Management Approaches Cultural One cultural approach is to find Culicoides breeding areas and drain them. However, identification of breeding areas is still being researched and producers aren’t knowledgeable on where they breed. Biological Some biological agents might control Culicoides but lack of knowledge on breeding habitats and biology of the insect has prevented the employment of biocontrol agents. Chemical Insecticides are generally not used for control of Culicoides, but the animal sprays listed for other livestock insects would provide at least some degree of control. Mosquitoes feed on virtually any animal. Although there are many different species and field biology may be different dependant on species, the ones that are livestock pests have similar life cycles. There are four stages: egg; larval or ‘wiggler’; pupal or ‘tumbler’ and adult. There are three main groups: Anopheles, Culex and Aedes. The Anopheles spp. lay eggs singly on the water surface. These eggs have ‘floats’ that prevent them from sinking. The Culex spp. lay eggs side-by-side and forms them into a ‘raft.’ The Aedes spp. lay eggs on moist substrates, where they await adequate moisture for hatching. The latter group is termed ‘flood water’ mosquitoes and they are most apt to be pest to cattle and horses. Animal Response and Economic Losses Cattle under heavy mosquito attack will bunch and spend time fighting mosquitoes instead of grazing. Steelman (1979) reported weight gain reductions of 0.04 kg/day/steer with heavy mosquito infestations. Management Approaches Cultural Moving cattle away from mosquito infested areas or placing them in shelter in the evening when most mosquito species are the most active have been suggested. However, for cattle in the west, this isn’t very practical because Aedes vexans, one of the major mosquito pests of cattle, is a daytime feeder. Other suggestions are to drain mosquito infested areas, if practical, for the floodwater mosquitoes. Biological There are mosquito-feeding fish that are efficient but not very practical for floodwater mosquitoes and they do not survive winter in northern climates. The bacterium Bacillus thurengensis var. israleiensis is formulated for mosquito control by several companies. Chemical Most of the suggested chemicals are biological for control of immature mosquitoes and there are numerous insecticides registered for adult mosquito control. Tabanids (horse and deer flies). The tabanids are a large diverse group of blood feeding flies. Adults range in size from 6 mm long (the size of a house fly) for the deer fly genera (Chrysops spp.) to as large as 30 mm long for the horse fly genera (Tabanus spp.). Only female tabanids feed on blood. Their mouthparts are stout and blade-like and inflict a deep painful bleeding wound. They inject an anticoagulant when they bite, which delays blood clotting. Eggs are deposited on vegetation, which overhangs or is near water. Newly hatched larvae fall in the water or mud when they hatch where they feed on organic debris. Most species have only one generation per year. Animal Response and Economic Losses Data on the economics of tabanid attacks on cattle are difficult to obtain because of mobility and lack of a good control method. Cattle under attack will seek water or shade and sometimes run trying to escape the flies. Perhaps the most serious economic impact on cattle is the transmission of anaplasmosis, a bacterial disease of cattle (once classified as a protozoan). Management Approaches Cultural Mowing vegetation around the edges of ponds has been shown to be effective in reducing numbers of at least one tabanid species in South Dakota. Chemical Insecticide sprays may provide some control for a short period of time. Insecticide sprays recommended for control of other livestock can be used for tabanids. Insecticide Suggestions for Treatment of Flies on Cattle (for horn and face flies see suggestions following horn fly section) Insecticide Application Application Method Rate Restrictions and comments Restricted-use Pesticide – Co-Ral products are not used on animals younger than three months of age. Coumaphos (Co-Ral ELI) Spray 11.6% ELI 2.5 oz/4 gal water (Co-Ral Fly and Tick Spray) Spray 6.15% EC 2 qt/50 gal water or 5 oz/4 gal water No more than six treatments per year. Do not make applications less than 10 days apart. (Co-Ral Plus) Ear tag 20% Coumaphos+ 20% Diazinon AI Two tags per animal Fenvalerate (Ectrin) Permethrin Ear tag 8.6% AI Two tags per animal. (Atroban DeLice) Pour-on 1% AI 15 ml(1/2 fl oz)/ 100 lb body wt Do not apply more than once every two weeks. Maximum of 5 oz per animal. (Atroban EC) Spray 11% EC 1 pt/25 gal water Spray to thoroughly wet animal. Do not apply more than once every two weeks. (Atroban Extra) Ear tag 10% Permethrin + 13% PBO Two tags per animal. (Boss) Pour-on 5% AI 3 ml/ 100 lb body wt Maximum of 30 ml per animal. Do not apply more than once every two weeks. (Ectiban) (Insectiban) Spray 5.7% AI 1 qt/25 gal water Spray to thoroughly wet animal. Do not apply more than once every two weeks. No treatment/slaughter interval. (GardStar) Spray 40% EC 4 oz/25 gal water (High pressure spray) Spray over whole body surface to thoroughly wet animal. Do not apply more than once every two weeks. (Longer residual control.) No Insecticide Application Application Method Rate Restrictions and comments treatment/slaughter interval. 4 oz/2.5 gal water (Low pressure spray) Spray midline from face to tail head until wet but do not allow runoff. Do not apply more than once every two weeks. (2-3 weeks residual control.) No treatment/slaughter interval. (Permectrin) Pour-on 1% AI Maximum of 5 oz per animal. Do not treat more 1/2 oz/100 lb body wt than once every two weeks. (Permectrin CDS) Pour-on 7.4% Permethrin + 7.4% PBO 1.5 ml/100 lb body wt Maximum of 15 ml per animal. (Permectrin II) Spray 10% AI 1 pt/100 gal water If necessary repeat in 14 days. No treatment/slaughter interval. (Permethrin) Dust bag 0.25% AI dust Do not use in pyrethroid resistant areas. (Synergized DeLice) Pour-on 1% Permethrin + 1% PBO 15 ml(1/2 fl oz)/ 100 lb body wt Maximum of 5 oz per animal. Do not treat more than once every two weeks. (Ultra Boss) Pour-on 5% Permethrin + 5% PBO 3 ml/100 lb body wt Maximum of 30 ml per animal. Do not apply more than once every two weeks. Mist, spray or wipe-on 0.05-1.0% Pyrethrins Follow label instructions. + Piperonyl Butoxide Many formulations of ready to use. Pyrethrins Cattle grubs (Hypoderma lineatum, H. bovis) are the larvae of heel flies. The adult is a large fly that resembles a bee in size and coloration. There are two species, the common (H. lineatum) and the northern (H. bovis). They are similar in appearance and biology, except the northern occurs about a month later than the common. Cattle are the only important hosts; preferred hosts appear to be yearlings, calves and older animals, in that order. Heel flies deposit eggs on the hairs of cattle, usually on the hind legs or belly. The larvae hatch and bore through the skin, usually at a hair follicle. The larvae spend about eight months migrating through the tissues of the animal and end up in the loin area of the back. Some states recommend a grub treatment cut-off date of December through January, because that is when most of the grubs are migrating through the esophagus (common grub) or the central nerve canal (northern). Dying grubs release a toxin, which causes swelling at the death site. The swelling in the esophagus causes bloating and swelling in the central nerve canal causes partial paralysis in the hindquarters. Veterinarians treat these symptoms with 2 PAM or atropine. The grub encysts in the back and completes their larval development. The cysts are termed warbles. A breathing hole is cut in the back, and the larvae emerge through the breathing hole when ready to pupate. The pupae fall to the ground and seek shelter in clumps of vegetation until they emerge as adults. The common grub emerges in late February or early March, and the northern grub emerges about a month later. The heel fly has no mouthparts and when mating and egg deposition have occurred, the adults die. Cattle being attacked for egg deposition will run trying to escape the fly. When running, they have their tails curled over their back, a behavior that is termed ‘gadding.’ As internal parasites, cattle grubs present in any number will cause reduced weight gains. When the breathing holes are cut, secondary infections often occur, and it is at this time that the grub has its greatest effect on the infested animals. Management Approaches Chemical There are several systemic insecticides available that provide excellent control. Systemic insecticides are absorbed through the skin and circulate internally. The older phosphate insecticides are still efficient, but have generally been replaced by the broad spectrum endectocides, which control both external and internal parasites (Ivomec and others). We recommend treatment only for cattle that will be at the ranch in February and March, the time of grub emergence from the back. Cattle purchased from ranches usually go through an animal health program and are treated for grubs and lice regardless of whether the original owner treated them or not. Insecticide Suggestions for Cattle Grubs Insecticide Application Method Application Rate Restrictions and comments Pour-on 5 mg/ml AI (0.5%) 1 ml/22 lb body wt Treatment-slaughter interval 45 days. Injection (IM) 10 mg/ml AI (1%) 1 ml/110 lb body wt Treatment/slaughter interval 35 days. Eprinomectin (Eprinex) Pour-on 5 mg/ml AI 1 ml/22 lb body wt No treatment-slaughter interval. Do not treat calves less than eight weeks old. Famphur (Warbex) Pour-on 13.2% AI 2 oz/100 lb body wt Do not exceed 4 oz Do not treat Brahma bulls, calves less than three months old, sick or stressed cattle, or use with other medication. Treatment-slaughter interval of 35 days. Doramectin (Dectomax) Insecticide Fenthion (Teguvon) Ivermectin (Ivomec) (Ivomec) (Phoenectin) (Prozap) Moxidectin (Cydectin) Application Method Application Rate Restrictions and comments Pour-on 3% AI 2 oz/100 lb body wt Do not treat calves less than 3 months old, sick or stressed cattle, or use with other medications or insecticides. Treatment-slaughter interval of 35 days. Spot-on 20% AI 4 ml/300 lb body wt Injection 1% AI 1 ml/110 lb body wt Treatment-slaughter interval 35 days. Pour-on 5 mg/ml AI (0.5%) 1 ml/22 lb body wt Treatment-slaughter interval 48 days. Do not use when rain is expected to wet cattle within six hours after treatment. Pour-on Injection 5 mg/ml AI 1 ml/ 22 lb body wt No treatment-slaughter interval. Cattle lice are small but they can cause economic losses to every cattle operation. There are four species of cattle lice that infest Northern cattle. They are the chewing louse (Damalinia bovis) which feeds on skin cells; the short-nosed louse (Haematopinus eurysternus) found in and on the ears, along the dewlap and brisket of mature cattle; the long-nosed louse (Linognathus vituli) found on young animals and dairy breeds; and the little blue louse (Solenopotes capillatus) that is difficult to control. Solenopotes capillatus is usually found in clusters on the front part of the animal, especially on the head, dewlap and neck. Infestations of S. capillatus have also been noted along the top line and under the tail. The life cycles of the four species are similar. Eggs (nits) are deposited on hair and the immature lice resemble adults and feed on the animal. The life cycle is usually completed in about a month. Reproduction rates decline in the summer and increase in the winter. Lice are spread by animal contact. Some animals have more lice than others, and these are termed ‘chronics’ or ‘carriers.’ Generally, when cattle are placed on a high nutrition ration, the lice populations will decline. Animal Response and Economic Losses High populations can cause anemia and affect the animal’s immune system, which makes it more susceptible to disease, particularly respiratory disease. Infested animals will scratch lice-infested sites and will have a rough-appearing haircoat. Weight gain depressions of 0.12 pounds per day have been recorded for cattle with a moderate to heavy lice population (7 or more) on both a growing and finishing ration. Management Approaches Cultural There are no known cultural practices for lice control except to cull chronic lice infested cattle from the herd. Chemical Lice numbers will be reduced when cattle are treated for cattle grubs in the fall. But the fall grub treatment may not be enough to prevent a lice buildup later in the winter. Insecticide Recommendations for Cattle Lice Insecticide Application Method Application Rate Restrictions and Comments Amitraz (Taktic) Spray 12.5% EC 0.025% AI 1 pt/50 gal water No restrictions. Apply spray to runoff. Cyfluthrin (Cylence) Pour-on 1% AI 4 ml/400 lb body wt Maximum of 12 ml Re-treat in three weeks. Coumaphos Restricted-Use-Pesticide Do not treat sick or stressed animals. Do not treat animals younger than three months. (Co-Ral ELI) Spray 11.6% ELI 5 oz/4 gal water (Co-Ral Fly and Tick Spray) Spray 6.15% EC 2 qt/50 gal water or 5 oz/4 gal water No more than six treatments per year. Do not make applications less than 10 days apart. Diazinon (OPtimizer) Ear tag 21.4% AI Two tags per animal. Not for use on lactating animals. No treatment/slaughter interval. (Warrior) Ear tag 40% AI Two tags per animal. No treatment/slaughter interval. Doramectin (Dectomax) Pour-on 5 mg/ml AI (0.5%) 1 ml/22 lb body wt Treatment-slaughter interval 45 days. Eprinomectin (Eprinex) Pour-on 5 mg/ml AI 1 ml/22 lb body wt No treatment-slaughter interval. Ivermectin (Ivomec) Injection 1% AI 1 ml/ 110 lb body wt Treatment-slaughter interval 35 days. Insecticide Application Method Application Rate Restrictions and Comments (Ivomec) Pour-on 5 mg/ml AI (0.5%) 1 ml/22 lb body wt Do not use when rain is expected to wet cattle within six hours after treatment. Treatmentslaughter interval 48 days. (Phoenectin) (Prozap) Lamdacyhalothrin (Saber) Pour-on 0.5% AI 1 ml/22 lb body wt Treatment-slaughter interval 48 days. Pour-on 1% AI 10 ml (1/3 fl oz) under 600 lb body wt 15 ml (1/2 fl oz) over 600 lb body wt Apply product down back line. Do not apply more than every two weeks, and no more than 4 times during a six month period. For sucking lice – two treatments at a 14-day interval recommended. Pour-on Injection 5 mg/ml AI 1 ml/22 lb body wt No treatment-slaughter interval. Spray 11.6% EC 1 qt/38 gal water Apply spray to point of runoff. Do not treat calves less than three months old, sick or stressed cattle. Treatment/slaughter interval 3 days. Permethrin (Atroban DeLice) Pour-on 1% AI 15 ml (1/2 fl oz)/100 lb body wt For optimum lice control, two treatments at 14day intervals recommended. Maximum of 5 oz per animal. (Atroban EC) Spray 11% EC 1 pt/25 gal water Spray to thoroughly wet animal. Do not apply more than once every two weeks. (Boss) Pour-on 5% AI 3ml/100 lb body wt Maximum of 30 ml per animal. For optimum lice control, two treatments at 14-day intervals recommended. (Brute) Pour-on 10% AI 3 ml/100 lb body wt For optimum lice control, two treatments at 14day intervals recommended. Apply from poll down neck over shoulders. No treatment/slaughter period. (Ectiban) (Insectiban) Spray 5.7% EC 1 qt/25 gal water Spray to thoroughly wet animal. (GardStar) Spray 40% EC 4 oz/25 gal water Spray over whole body surface to thoroughly wet animal. Do not apply more than once every Moxidectin (Cydectin) Phosmet (Del-Phos) Insecticide Application Method Application Rate Restrictions and Comments (High pressure spray) two weeks. (Longer residual control.) No treatment/slaughter interval. 4 oz/2.5 gal water (Low pressure spray) Spray midline from face to tail head until wet but do not allow runoff. Do not apply more than once every two weeks. (2-3 weeks residual control.) No treatment/slaughter interval. (Permectrin) Pour-on 1% AI 2 oz/100 lb body wt Maximum of 5 oz per animal. Do not treat more than once every two weeks. (Permectrin CDS) Pour-on 7.4% Permethrin + 7.4% PBO 2 ml/100 lb body wt Maximum of 20 ml per animal. (Permectrin II) Spray 10% EC 1 pt/100 gal water Repeat in 14 – 21 days. (Synergized DeLice) Pour-on 1% Permethrin + 1% PBO AI 15 ml (1/2 fl oz)/100 lb body wt Do not apply more than once every two weeks. Maximum of 5 oz per animal. (Ultra Boss) Pour-on 5% Permethrin + 5% PBO AI 3 ml/100 lb body wt Maximum of 30 ml per animal. For optimum lice control, two treatments at 14-day intervals recommended. (PYthon) Ear tag 10% Zetacypermethrin + 20% PBO (9.5 g) Apply two tags per animal for control up to five months. No treatment/slaughter interval. (PYthon Dust) Dust bag 0.075% Dust Zetacypermethrin + 0.15% PBO No restrictions – apply up to 2 oz/animal as necessary but not more often than every three days. (PYthon Magnum) Ear tag 10% Zetacypermethrin + 20% PBO (15.4 g) Apply only 1 tag per animal and do not apply to calves less than 3 months old. No treatment/ slaughter interval. (used for biting lice) Zetacypermethrin Mites (Cattle Scabies). Mites, like ticks, are members of the class Arachnida, so they have two main body parts and four pairs of legs on the adults but only three pairs on the immature mites. There are three cattle scabies species: Psoroptic scabies (Psoroptes ovis), Sarcoptic scabies (Sarcoptes scabiei) and Chorioptic scabies (Chorioptes bovis). A fourth mite (Demodex bovis), the cattle follicle mite, may also be found in cattle. The Psoroptes mite is the most serious scab mite and requires reporting and quarantine. The other three species are more of a problem for dairy cattle in the Northeast part of the U.S. Mites attack any part of the body, particularly areas of thick hair. Lesions most commonly occur on the withers, along the back and around the tail. Symptoms of mites may not be evident until winter because, like cattle lice, the reproduction rates of mites increase during cool weather and decrease during hot weather. The life cycle is as short as 10-12 days during the winter. Animal Response and Economic Losses Mites spread from animal to animal by contact. The Psoroptic scabies mites do not burrow in the skin as do the other species but their feeding causes severe skin irritation and itching. Rubbing and scratching by the animal further irritates the infested area. Eventually, a scab forms providing a sheltered and optimum situation for the mite that allows them to increase rapidly. Infested animals fail to do well and loss of hair during the winter can cause the animal’s death. Management Approaches Scabies infested cattle must be treated with either ivermectin or eprinomectin. Ticks. Ticks are members of the same phylum (Arthropoda) in the animal kingdom as insects but are in a different class (Arachnida). The main difference is the body of a tick is composed of only two sections while insects have three sections and adult ticks have four pairs of legs while insects have three pairs of legs. Ticks found in the U.S. are divided taxonomically into two main families – the hard ticks (Ixodidae) and soft ticks (Argasidae). The hard ticks are flattened dorsoventrally in the unfed state, possess a marginal outline which tapers toward the anterior and the mouthparts are clearly visible. They have a sclerotized dorsal shield (scutum) which is often ornate with patterns in white or gold against a brown or gray background. The soft ticks have an oval or pear-shaped outline with the anterior body region broadly rounded with a granulated leathery appearance. They lack the sclerotized dorsal shield and the mouthparts are difficult to see without magnification. Ticks may also be classified on the basis of life cycle as one-, two- or three-host ticks. The majority of the U.S. tick species are one- or three-host ticks. Most species feed on blood three times during their life cycle. The one-host ticks (i.e. winter tick) remain attached to the host during all three blood feeding times while the three-host ticks (i.e. lone star tick) feed, drop off and reattach later on progressively larger hosts. The tick life cycle includes four stages: egg, six-legged larvae, eight-legged nymphs and the adult. Engorged female ticks deposit large numbers of eggs either in one large batch (several thousand) or several smaller batches. The eggs hatch into small six-legged larvae (seed ticks). Seed ticks crawl up on vegetation and seek hosts by ‘questing’ and attaches itself to the host animal as it passes. During ‘questing,’ ticks hang by their back legs thus leaving their front legs, equipped with the organ of Haller, free to wave in the air and detect CO2 from a perspective host. Once attached, the seed tick feed on blood and either remain on the animal (one-host tick) or drop off to reattach later as a nymph. After feeding, the nymph drops off and changes to the adult which will reattach later. The survival rate for seed ticks, nymphs and even adult ticks is very low because of a hostile environment or difficulty finding a host. This is offset however, by the great number of eggs deposited by the female and the capacity of all stages to survive long periods without feeding. Animal Response and Economic Losses Globally, ticks are the most serious ectoparasite of livestock. They cause serious livestock losses in Africa, Australia, Central and South America and the southern half of the U.S. Ticks affect livestock in several ways: physiologically by irritation, allergic response, loss of blood which may result in reduced weight gains, weight loss, disease transmission (anaplasmosis, babesiosis (Texas cattle fever), and epizootic bovine abortion) and paralysis as well as damage to carcasses, fleece and hides from tick feeding. Despite the magnitude of the tick problem to livestock, studies that relate tick numbers to economic losses are rare in the literature. Ticks are not usually numerous enough to be a major economic problem in the Northern Great Plains but are occasionally. The major species are the Rocky Mountain wood tick Dermacenter andersoni; American dog tick D. variabilis; brown dog tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus; lone star tick Amblyomma americanum; winter tick D. albipictus and the “spinose” ear tick Itobius meginini. The lone star tick and the winter tick may be expanding their range. The lone star tick was found in the central Sandhills of Nebraska in 2002, and the winter tick in west central Nebraska in 2002, both were new county records for those areas. Management Approaches Cultural Cultural practices used in some areas with high numbers of ticks annually is brush removal, mowing the vegetation next to wooded areas, rotating cattle away from the most tick-infested pastures and the use of tick resistant cattle breeds. None of these methods are practical for the Northern Great Plains. Chemical The insecticides registered as sprays for other ectoparasites of livestock will control ticks in our area. Resistance has been reported in Texas and Mexico to some of the acaricides used for ticks, but treatment in our area is so infrequent there should be no resistance problem. Information compiled by: Sherry White; MSU - Department of Entomology Acknowledgements Edited by: John Paterson; MSU – Extension Beef/Cattle Specialist, Department of Animal and Range Sciences John Jackson; Consultant Thank you to the county agents who responded to the livestock profile survey. Contacts: Pesticide Applicator Training/Education Reeves Petroff Montana Pesticide Education and Safety Program PO Box 173020, Montana State University Bozeman, MT 59717-3020 Phone: (406) 994-3518 Fax: (406) 994-6029 References: Crop Profile for Beef Cattle Production in South Dakota (2002) Crop Profile for Beef Cattle (Pasture and Range) in Kansas (2000) High Plains IPM Guide – Cattle Insect Pests (http://highplainsipm.org/HpIPMSearch/CattleIndex.html) Mock, D.E. 1997. Managing insect problems on beef cattle. Kansas State University Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension Service, C-671 (Revised). United State Department of Agriculture (USDA)/National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS)/Montana Agricultural Statistics Service/Montana Livestock State-Level Statistics. 2003//2004.