Microsoft Word - UWE Research Repository

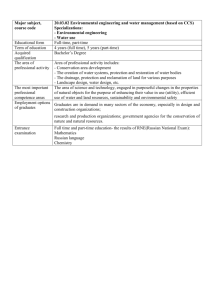

advertisement