Within a sociocultural environment that emphasizes the attracti

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 1

Running Head: HYPERCOMPETITIVENESS AND DISORDERED EATING

The Relationship between Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating:

A Comparison of Scholarship versus Non-Scholarship Female Cross-Country Runners

Amanda L. Williams, Robert A. Swoap, Ph.D., & Kathryn A.P. Burleson, Ph.D.

Warren Wilson College

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 2

Abstract

The current study marks the first attempt to examine the possible relationship between athletic scholarship, hypercompetitiveness, and disordered eating among female collegiate cross-country runners. One-hundred and sixteen runners from 15 NCAA

Division I and Division III athletic programs completed the Hypercompetitive Attitude

(HCA) Scale and the Eating Disorder Inventory-3 (EDI-3). Although the HCA Scale and

EDI-3 were found to be significantly correlated ( r = .54, p < .001), D-I scholarship runners ( n = 42) did not obtain significantly higher scores than non-scholarship runners

( n = 74). These results suggest that, irrespective of competition level or scholarship status, athletes whose self-esteem relies too heavily on competitive outcomes should be closely monitored for unhealthy eating attitudes and behaviors.

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 3

The Relationship between Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating: A Comparison of Scholarship versus Non-Scholarship Female Cross-Country Runners

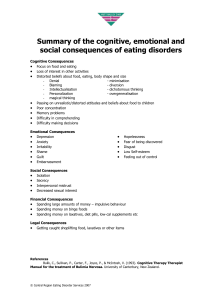

Within a sociocultural environment that emphasizes the attractiveness of a thin and feminine physique, unhealthy attitudes toward eating have become an increasingly pervasive problem within female populations (Taub & Blinde, 1992). Disordered eating encompasses a broad spectrum of abnormal eating behaviors, ranging from sociallyaccepted dieting to the life-threatening illnesses of anorexia and bulimia nervosa

(Academy for Eating Disorders, 2007, Diagnoses of Eating Disorders section; Faer,

Hendriks, Abed, & Figueredo, 2005). Although clinical eating disorders are diagnosed in only 3% of late adolescent and adult women, it has been estimated that over 10% of women display symptoms of eating disorders at any given time (Academy for Eating

Disorders, 2007, Prevalence of Eating Disorders section, para. 1-2). Anecdotal and empirical findings suggest that eating disorders are acquired and spread through a social contagion effect in which groups of similarly-aged women establish and maintain social norms for dieting and thinness (Crandall, 1988).

This social contagion effect may be further intensified within the competitive realm of elite athletics. In particular, elevated rates of disordered eating have been observed within endurance sports, such as cross-country, that emphasize leanness for optimal performance (Johnson, Powers, & Dick, 1999; Picard, 1999; Taube & Blinde,

1992). Although this emphasis on performance thinness appears to have serious implications on the health of the female cross-country runner, contradictory findings from various other studies have made it difficult to identify additional personality traits or elements of competition that may increase the female runner's risk of developing an

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 4 eating disorder. The current research proposes that a maladaptive form of competitiveness, known as hypercompetitiveness, and the pressure to maintain an athletic scholarship may be related to unhealthy eating attitudes and body dissatisfaction within a population of female cross-country runners.

Disordered Eating within Athletics

There is considerable disagreement within the existing body of literature on the prevalence of disordered eating within athletics. For example, although an extensive

National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) study suggested that female collegiate athletes are at a significant risk for developing disordered eating, the study also suggested that the prevailing rates of symptomatic behaviors and attitudes are not as high as previously reported (Johnson, Powers, & Dick, 1999). However, of the hundreds of female athletes surveyed, 25% were at risk for developing anorexia and an alarming 58% were at risk for bulimia (Johnson, Powers, & Dick, 1999). In contrast, other studies have contended that athletes are no more likely to develop eating disorders than the rest of the general population (Weight & Noakes, 1987). Existing literature seems to support both of these findings; researchers have estimated that as few as 1% to as many as 60% of athletes exhibit symptoms of disordered eating (Carlton, 2007). Furthermore, past research suggests that the prevailing rates of disordered eating among college athletes may be the result of a multitude of extremely complex interactions between certain maladaptive personality traits and social pressures to maintain a thin physique for optimal athletic performance (Berry & Howe, 2000).

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 5

Personality Correlates of Disordered Eating in Athletics

Thompson and Sherman's “good athlete” paradigm.

In a competitive environment that rewards personal sacrifice and commitment to rigorous physical training, certain personality traits and behaviors that are indicators of unhealthy attitudes toward eating and gaining weight may be misperceived as assets of a

“good athlete” (Thompson & Sherman, 1999b). According to Thompson and Sherman

(1999b, p.188), “The athlete who works excessively, denies pain and injury, is selflessly committed to the team, and accepts nothing but perfection, not to mention is willing to lose weight to be ‘better', is exactly what many coaches are looking for in an athlete.”

Within athletics, individuals who have a perfectionist orientation, possess high selfexpectations, and exhibit intense self-discipline generally receive reinforcement for their unwavering commitment to excellence (Thompson & Sherman, 1999b; Taub & Blinde,

1992; Picard, 1999). When taken out of the context of sport, however, these characteristics are more closely associated with personality correlates of eating disorders,

(i.e. asceticism, perfectionism, fear of rejection, selflessness, body dissatisfaction, and internalized pressure to be slim) (Picard, 1999; Thompson & Sherman, 1999b; Taub &

Blinde, 1992; Berry & Howe, 2000). These personality correlates are more commonly reported by female athletes than their male counterparts and also tend to be highly correlated with lower scores on measures of self-esteem (Johnson, Powers, & Dick,

1999). This suggests that “good athlete” personality traits may become more maladaptive when exposed to cultural expectations of femininity and sport-specific norms emphasizing performance thinness.

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 6

Although there is considerable empirical support for Thompson and Sherman's

(1999b) “good athlete” paradigm, other studies have found that athletes generally display significantly higher levels of self-esteem and body satisfaction than non-athletes (Steiner,

Pyle, Brassington, Matheson, & King, 2003; Taub & Blinde, 1992). These findings have led some people to theorize that within the context of sport, restrictive or disordered eating is not a psychopathological behavior (Davis & Strachan, 2001; Taub & Blinde,

1992). This view contends that athletes who develop eating disorders are merely displaying an over-commitment to athletic excellence. However, Davis and Strachan’s

(2001) study of patients in an eating disorder clinic found that patients who had previously competed in athletics did not differ from other eating disordered patients on measures of obsessive-compulsiveness, narcissism, and neurotic perfectionism. This finding cautions against the dismissal of an athlete’s disordered eating as a purely behavioral response to the external pressures of athletics. Oftentimes, coaches do not recognize the psychopathology of their athletes' restrictive eating habits until the athletes suffer career-ending injuries or develop full-blown eating disorders (Scott, 2006).

Although there is disagreement about whether or not disordered eating and excessive training are psychopathological within the context of elite athletics, numerous studies have suggested that maladaptive perfectionism and competitiveness are personality correlates of eating disorders across a myriad of settings. Striegel-Moore,

Silberstein, Grunberg, and Rodin (1990) found that college women who were intensely competitive and perfectionist in orientation were more likely to display symptoms of eating disorders. This finding led the authors to speculate that a strong underlying desire to win in interpersonal situations may compel women to compete with others in terms of

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 7 weight and eating behaviors. Furthermore, Faer, Henriks, Abed, and Figuerdo (2005) found that female competition for romantic partners and social status was significantly correlated with perfectionism, highly competitive behaviors, and a win-at-all-costs attitude among women presenting eating disorder symptoms. Faer et al. (2005) also observed that women with anorexia nervosa were more likely than their peers to use intense self-control and dieting behaviors in their pursuit of perfection.

These dangerously competitive attitudes are also commonly observed in perfectionist athletes who set excessively high standards for themselves, are overly critical of mistakes, are worried about rejection, possess low self-esteem, and express acute dissatisfaction with body shape and athletic performance (Gotwals, Dunn, &

Wayment, 2003; Thompson & Sherman, 1999b). An athlete’s persistent dissatisfaction with perceived shortcomings may predispose them toward emulating eating-disordered teammates whose weight loss may have created an initial spike in performance (Stout,

2007). Also, the stress of transitioning into a competitive college environment and competing at a more elite level may exacerbate an athlete’s predisposition toward disordered eating and obsessive exercise (Stout, 2007). Communal living, locker rooms, and revealing uniforms may also exploit maladaptive perfectionism and competitiveness by exposing women to each other’s bodies on a daily basis (Striegel-Moore et al., 1990;

Thompson & Sherman, 1999a).

Hypercompetitiveness.

One specific form of competitiveness, known as hypercompetitiveness, has been shown to be highly correlated with disordered eating behaviors and intense motivation to achieve in appearance, academics, and career (Burckle, Ryckman, Gold, Thornton, &

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 8

Audesse, 1999). Karen Horney defined hypercompetitiveness as the “indiscriminate need by individuals to compete and win (and avoid losing) at any costs as a means of maintaining or enhancing feelings of self-worth, with an attendant orientation of manipulation and denigration of others across a myriad of situations” (as cited in

Ryckman, Thornton, & Butler, 1994, p.84). Horney also wrote that the hypercompetitive individual’s overly ambitious expectations lead to perpetual disappointment and dissatisfaction. Furthermore, Ryckman, Thornton, and Butler (1994) found that individuals with a hypercompetitive attitude (HCA) tend to obtain high scores in measures of narcissism, neuroticism, and Type E personality traits. Type E individuals strive to be everything to everyone, and as a result, experience role overload. This strong need to please is also commonly found in individuals with eating disorders and is one of the personality traits described in the “good athlete” paradigm (Thompson & Sherman,

1999b). Other areas of overlap between HCA and eating disorders include mistrust, low self-esteem, and low optimal psychological health (Ryckman, Thornton, & Butler, 1994;

Mintz & Betz, 1988). Kog, Vandereycken, and other psychodynamic researchers observed that individuals with an HCA and/or eating disorder tend to come from similar family backgrounds that fostered feelings of insignificance and powerlessness (as cited in

Burckle et al., 1999). Burckle et al. (1999) theorized that these individuals may by utilizing hypercompetitiveness and disordered eating to regain some sense of control in their lives.

Hypercompetitiveness in athletics.

Within the realm of athletics, HCA is associated with an ego-oriented and individualistic desire to gain social status, obtain a higher status career, bolster self-

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 9 esteem, and learn competitive skills (Ryska, 2002a). In addition, male and female athletes with high levels of hypercompetitiveness tend to place more emphasis on social comparison, have decreased self-regard, and decreased physical ability self-esteem

(Ryska, 2002b). They also tend to exhibit reduced effort pending failure and display lower task persistence.

Although past studies have linked HCA with maladaptive personality traits, none have examined the possible relationship between HCA and disordered eating within a population of female athletes. Burckle et al.'s (1999) study only demonstrated that HCA was related to disordered eating within the competitive realms of academics, career, and appearance. There has been no previous mention of any correlation between HCA and disordered eating within a highly competitive athletic environment.

Athletic Scholarship and Level of Competition

The majority of past research studies have suggested that athletes performing at more elite levels of competition are more likely to display symptoms of eating disorders than their lower-tier counterparts. Weight and Noakes’ (1987) survey of South African distance runners found that although only 14% possessed abnormal eating attitudes, 80% of these “at-risk” runners were highly competitive and elite athletes. A similar trend was noted in a survey of NCAA Division-I (D-I) and Division-III (D-III) coaches (Heffner,

Ogles, Gold, Marsden, & Johnson, 2003). D-I coaches reported engaging in more monitoring and management of their athletes’ eating behaviors, had more experiences with athletes displaying eating disturbances, and possessed more available resources for helping their athletes overcome unhealthy behaviors.

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 10

Division-I institutions are typically larger universities that offer athletic scholarships to highly talented and recruited individuals; D-III colleges do not offer athletic scholarships and place more emphasis on the personal growth of the athlete

(Heffner et al., 2003). When comparing D-I athletes to their D-III counterparts, Picard

(1999) found that D-I athletes reported higher subjective levels of competitiveness and pressure to perform. D-I athletes also obtained significantly higher scores on measures of disordered eating behaviors and attitudes. The most dramatic difference was noted on the

Drive for Thinness subscale of the Eating Disorder Inventory (EDI). Although Picard’s

(1999) study demonstrated that the level of competition may have an effect on the prevalence of disordered eating, it did not examine if this effect could be partially attributed to the pressures of maintaining a D-I athletic scholarship. The increasingly competitive nature of female intercollegiate athletics and the consistent rise in college tuition rates suggests that today’s female athletes may be faced with greater pressures to perform. Although one 1979 study examined the possible relationship between athletic scholarship and the female athlete's total self-concept, no study has ever examined the possible relationship between athletic scholarship and disordered eating (Dowd, 1979).

Cross-Country Runners

While researchers disagree on the actual rate of eating disorders in college athletics, there appears to be strong evidence for a relationship between disordered eating and sports that emphasize leanness for optimal performance. Cross-country runners and other lean-sport athletes are more likely to express a distinct fear of fatness, have a greater drive for thinness, and experience acute feelings of self-discipline, denial, and control (Picard, 1999). When compared to other athletes, cross-country runners have been

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 11 found to be at an increased risk for atypical eating, body dissatisfaction, and maladaptive perfectionism (Picard, 1999; Taub & Blinde, 1992). A significantly higher percentage of lean-sport athletes report menstrual dysfunction than their non-lean counterparts

(Torstveit & Sundgot-Borgen, 2005). Menstrual dysfunction, or amenorrhea, is related to excessive dieting, pathogenic weight control methods, rigorous exercise, and energy deficiency. Over time, amenorrhea can lead to decreased bone density and osteoporosis.

Although medical experts have identified amenorrhea as one of the main physical symptoms of an eating disorder, many misinformed coaches and athletes have been led to believe that menstrual dysfunction is a normal part of intense training (Thompson &

Sherman, 1999a). Johnson, Powers, and Dick’s (1999) study found that a large percentage of D-I female athletes aspired toward achieving a body fat content that would result in amenorrhea. Because cross-country runners have been identified as being more susceptible to the “female athlete triad” of disordered eating, menstrual dysfunction, and osteoporosis, it seems imperative that more research be conducted to examine the risk factors that underlie this dangerous trend.

Although not all athletes who aspire toward a low body fat content display disordered eating behaviors, it appears as if lean-sport athletes who are highly perfectionistic and competitive in orientation are more likely to exhibit symptoms of anorexia and bulimia nervosa. The current study marks the first attempt to examine the possible relationship between athletic scholarship, hypercompetitiveness, and disordered eating among female collegiate athletes, specifically cross-country runners. I hypothesize that:

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 12

I) When compared to Division III athletes, Division I athletes will

(a) Obtain higher scores on self-report measures of the following personality correlates of disordered eating:

1) Perfectionism

2) Body dissatisfaction

3) Asceticism

4) Drive for thinness

(b) Report a higher pressure to perform

(c) Display more hypercompetitive attitudes than D-III athletes

II) Hypercompetitiveness will be positively correlated with the following personality correlates of eating disorders: body dissatisfaction, bulimia, drive for thinness, perfectionism, asceticism, and low self-esteem

III) There will be an interaction, such that the greatest vulnerability to disordered eating will be reported by D-I scholarship athletes who report the highest levels of hypercompetitiveness

Method

Participants

One-hundred and sixteen female intercollegiate cross-country runners from seven

NCAA Division I and eight Division III programs participated in the current study. The sample of Division I runners ( n = 62) was comprised of both scholarship ( n = 42) and non-scholarship ( n = 20) athletes. Because Division III institutions do not offer athletic scholarships, the runners ( n = 54) from these schools provided data that was solely representative of non-scholarship athletes. The average age of the participants was 19.46

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 13 and the majority of runners were Caucasian (94%). Two African-American (1.7%), three

Asian/Pacific Islander (2.6%), and two Hispanic (1.7%) women participated in the study.

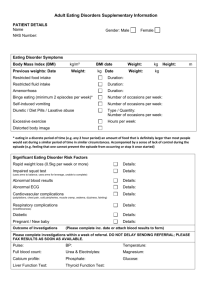

Measures

A Background Information Questionnaire obtained the athlete's age, ethnicity, and whether or not they received an athletic scholarship. Scholarship athletes were asked to indicate perceived level of pressure to maintain scholarship status on a Likert-type scale (0 = None to 10 = Extremely High). An additional question examined the degree to which scholarship and non-scholarship participants felt pressured by their coaches to excel (0 = Not At All Pressured to 10 = Extremely Pressured).

The 26-item Hypercompetitive Attitude Scale (HCA; Ryckman, Hammer, Kaczor,

& Gold, 1990) assesses individual differences in hypercompetitiveness. The HCA scale has been found to be both valid and reliable, with an alpha of .91 reflecting strong internal consistency and a high test-retest reliability of r =.81. Participants respond to statements on a 5-point Likert scale: never true of me (1), seldom true of me (2), sometimes true of me (3), often true of me (4), and always true of me (5). Scores range from 26 to 130, with higher scores indicating stronger hypercompetitiveness. Sample items include “I really feel down when I lose in athletic competition” and “I find myself being competitive even in situations that do not call for competition.”

The Eating Disorder Inventory-3 (EDI-3; Garner, 2004) is a self-report measure of psychological traits and constructs that have been indicated as being clinically relevant in individuals with eating disorders. The EDI-3 is an updated version of the original EDI

(Garner & Olmstead, 1984), a highly reliable instrument used in clinical and research settings. The current EDI preserves the integrity of the original test, with the reliabilities

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 14 for its scales ranging from the high .80s to the .90s. The inventory's 91 items are divided into 12 primary scales: drive for thinness, bulimia, perfectionism, low self-esteem, body dissatisfaction, personal alienation, interpersonal insecurity, interpersonal alienation, interoceptive deficits, emotional dysregulation, asceticism, and maturity fears. These scales yield six composites; the current study focuses on scores from the Eating Disorder

Risk, Overcontrol, and General Psychological Maladjustment composites. The Eating

Disorder Risk Composite reliability ranges from .90-.97 (median = .94) across four diagnostic groups and three normative groups. The test-retest reliability coefficients for the various composite scales are between .93 and .98. The EDI-3 asks participants to indicate if items are true of them always (A), usually (U), often (O), sometimes (S), rarely

(R), or never (N). These items include statements such as: “I am preoccupied with the desire to be thinner” and “I feel extremely guilty after overeating.”

Procedure

Division I and Division III cross-country programs from across the southeastern, midwestern, and mid-Atlantic regions were selected through methods of convenience and snowball sampling. Letters were sent to the cross-country coaches of selected programs via conventional mail and/or electronic mail. It was emphasized that the current study was being conducted solely for research purposes and that the names of individual programs and participants would not be included in the results. An outline of the procedures and contact information were also provided. Letters emphasized that although coaches would not have access to their team's individual scores, they would be able to access general results from the completed study on the Warren Wilson College

Psychology website. A copy of the HCA, EDI-3, and informed consent form were

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 15 included for their review. Coaches who were interested in participating were asked to provide the email addresses of their team captains, sports nutritionists, or athletic trainers.

Of the 209 programs contacted, 15 allowed their athletes to participate (7.7%).

Once permission was obtained from a coach, the primary researcher emailed a general description of the study to the team captain, sports nutritionist, or athletic trainer and asked him or her for a campus mailing address. Beginning in August, each volunteer was sent instructions for test administration, participants' test packets, consent forms, and a self-addressed envelope with return postage. The instruction letter asked volunteers to distribute informed consent forms and test packets to any teammates interested in participating in the study and were at least 18 years of age. Volunteers were asked to reemphasize that participation was voluntary, anonymous, and confidential. Team members were also informed that the coach would not have access to their completed tests and that their participation in the study would not affect their position on the team.

Volunteers then instructed their team to complete the test packets and consent forms in a place with privacy and minimal distraction. Sixty percent of the 193 eligible athletes turned in completed packets. Athletes who wished to receive general feedback on their individual performances on the HCA and EDI-3 were asked to write down their email address on the demographics questionnaire.

Test packets were generally completed within 30 minutes. Sealed test packets were handed to the research volunteers, who then placed the sealed packets in the provided envelope and mailed them to the primary researcher.

Packets that were missing more than 15% of the necessary data were excluded from the study. Eight entire packets were excluded due to missing questionnaire and

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 16 demographic data. For packets that were missing a negligible amount of data, means were calculated for replacing missing variables.

After compiling and entering data into a password- protected computer program

(SPSS), the primary researcher sent feedback to participants who indicated that they were interested in receiving this information. Twelve athletes whose responses suggested that they may have concerns regarding body weight, body shape, and/or eating were encouraged to speak with their college counselor. All athletes were encouraged to contact the primary researcher if they had any further questions.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The overall sample's mean scores on the HCA Scale and the EDI-3 were 71.58

( SD = 12.31) and 76.11 ( SD = 43.68), respectively. Additional means and standard deviations of the various EDI-3 subscales and composites are provided in Table 1.

Descriptive statistics were also obtained from the background information questionnaire, which asked athletes to indicate perceived pressure to excel and maintain athletic scholarship. In general, the majority of athletes reported moderate pressure from coach to excel ( M = 5.36, SD = 2.99) and similarly moderate levels of perceived pressure to maintain scholarship ( M = 5.68, SD = 2.45), with scores ranging from 0 to 10. In order to run primary analyses regarding the hypothesized influence of level of competition and scholarship status on HCA, EDI-3, and perceived pressures to excel and maintain athletic scholarship, the participants were divided into the following groups: Division I

Scholarship, Division I Non-Scholarship, and D-III Non-Scholarship. Means for these groups are provided in Table 1.

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 17

Table 1

Mean Scores and Standard Deviations on HCA, EDI-3, and Perceived Pressure Variables by

Division and Athletic Scholarship

Variable

1. HCA

2. EDI

2a.EDRC

DT

Scholarship

(n = 42)

Division I

Non-Scholarship

(n = 20)

Total

(n = 62)

Division III

Total

(n = 54)

70.9 (12.14) 73.85 (12.18) 71.85 (12.14) 71.26 (12.62)

75.93 (38.27) 71.1 (28.41) 74.37 (35.22) 78.15 (52.15)

21.88 (14.82) 19.6 (14.64) 21.15 (14.68) 22.69 (19.22)

B

BD

2b.OC

P

6.1 (5.75)

5.4 (5.34)

4.95 (4.16)

3.5 (3.82)

5.73 (5.29) 6.81 (6.58)

4.79 (4.95) 4.31 (4.89)

10.38 (6.71) 11.15 (9.73) 10.63 (7.74) 11.56 (10.07)

15.71 (6.94) 14.8 (6.35) 15.42 (6.72) 16.37 (8.21)

A

10.69 (5.24) 10.25 (5.1) 10.55 (5.16) 11.07 (4.67)

5.02 (2.87) 4.55 (2.8) 4.87 (2.83) 5.3 (5.3)

54.05 (26.77) 51.5 (16.73) 53.23 (23.88) 55.28 (36.27) 2c.GPMC

LSE

3. Coach’s Pressure

4. Scholarship Pressure

3.64 (3.54)

5.95 (2.5)

5.36 (2.99)

3.75 (3.82)

5.05 (2.24)

3.68 (3.6)

5.66 (2.44)

4.11 (4.89)

5.7 (2.49)

Note. EDRC = Eating Disorder Risk Composite; DT = Drive for Thinness; B = Bulimia;

BD = Body Dissatisfaction; OC = Overcontrol Composite; P = Perfectionism; A =

Asceticism; GPMC = General Psychological Maladjustment Composite; LSE = Low

Self-Esteem. EDRC is a sum of scores obtained on DT, B, and BD subscales of the EDI.

OC is calculated by adding the P and A scores together. GPMC is a composite score of the EDI-3's nine psychological subscales.

Hypothesis 1

Contrary to the hypothesis that athletes at higher levels of competition would obtain higher scores on the EDI-3, D-III athletes actually obtained higher mean scores than D-I athletes ( see Table 1). However, an independent samples t-test with a 95% confidence interval revealed that this difference in scores was not significant ( t (113) =

-.45, p = .66). Likewise, there was no significant difference in the EDI-3 scores of scholarship and non-scholarship athletes ( t (113) = .04, p = .97).

Additional t-tests revealed no significant differences between D-I athletes and D-

III athletes on the following EDI-3 subscales: Drive for Thinness ( p = .33), Body

Dissatisfaction ( p = .58), Perfectionism ( p = .57), and Asceticism ( p = .60). A

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 18 comparison of scholarship to non-scholarship runners on the same subscales found similarly weak differences, with respective p values of p = .85, p = .49, p = .87, p = .92.

Furthermore, level of competition and scholarship status were not found to account for a statistically significant difference in scores on the HCA Scale. An independent samples t-test with a 95% confidence interval revealed no significant difference between the HCA scores of Division I athletes and Division III athletes

( t (111) = .26, p = .80). There was also no significant difference in scores when comparing scholarship athletes to non-scholarship athletes ( t (114) = .45, p = .66).

Exploratory analyses revealed that D-I athletes and D-III athletes reported similar levels of perceived pressure from their coaches to excel; there was no significant difference between the two groups ( t (111) = -.10, p

= .92). Pearson’s correlation tests found this particular form of pressure to be significantly related to hypercompetitiveness, though the relationship was not very strong ( r = .17, p < .05). Pressure from coach to excel was also significantly correlated with pressure to maintain athletic scholarship ( r =

.46, p < .001) and the Perfectionism ( r = .23, p < .005) subscale of the EDI-3.

Additional exploratory analyses found that pressure to maintain scholarship was significantly correlated with scores on the HCA Scale ( r = .30, p < .005) and the EDI-3's

Drive for Thinness ( r = .31, p < .05) and Perfectionism ( r = .29, p < .05) subscales.

However, the proposed relationship between pressure to maintain scholarship and the

EDI-3's Eating Disorder Risk Composite was not found to be significant ( r = .20, p =

.

10).

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 19

Hypothesis 2

A series of Pearson's correlations were conducted to examine the hypothesized relationship between hypercompetitiveness and disordered eating. It was predicted that the HCA would be positively correlated to several of the EDI-3's subscales. As anticipated, the HCA Scale was found to be significantly correlated with overall scores on the EDI-3 ( r = .52, p < .001) and all of the EDI-3 subscales of interest, as shown in

Table 2. Because these correlations were computed by collapsing data across all divisions, means and standard deviations from the entire sample of 116 runners are provided ( see Table 2).

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 20

Table 2

Correlations between EDI-3 Subscales and Hypercompetitiveness

Subscales

1. Eating Disorder Risk Composite (EDRC)

M = 21.86

SD = 16.89

Drive For Thinness (DT)

M = 6.23

SD = 5.92

Bulimia (B)

M = 4.57

SD = 4.91

Body Dissatisfaction (BD)

M = 11.06

SD = 8.87

2. Overcontrol Composite (OC)

M = 15.86

SD = 7.43

HCA

.44*

.37*

.4*

.38*

.5*

Perfectionism (P)

M = 10.79

SD = 4.92

.42*

Asceticism (A)

M = 5.07

SD = 4.15

.4*

.51 * 3. General Psychological Maladjustment (GPMC)

M = 54.17

SD = 30.1

Low Self-Esteem (LSE)

M = 3.88

SD = 4.23

*p < .001.

.36*

Hypothesis 3

Because there were no significant difference between the scores of scholarship athletes and non-scholarship athletes on any of the variables of interest, it was decided that there was not enough statistical support for additional tests looking at whether or not

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 21

D-I scholarship athletes with high levels of hypercompetitiveness reported higher eating disorder risk than their non-scholarship counterparts.

Interpretation of EDI-3 Scores

When using the EDI-3 for diagnostic purposes, clinicians convert the raw scores to t-scores that compare the individual's responses to a proper clinical reference group.

These clinical groups include anorexia nervosa- restricting type, anorexia nervosa- bingeeating/purging type, bulimia nervosa, and eating disorders not otherwise specified

(Garner, 2004). However, because the current study did not assess physiological (such as body mass index) or behavioral symptoms of disordered eating, individual raw scores were not converted to t-scores. Raw scores were used for comparison to Garner's (2004)

US Adult Combined Clinical Sample and for correlation analyses and tests of significance.

A comparison between the participants of the current study and Garner's (2004)

US Adult Combined Clinical Sample found that, in general, only a small percentage (1-

3%) of the participating athletes obtained scores within the elevated, or high-risk, clinical range on the majority of the EDI-3 subscales. However, a rather substantial percentage of athletes obtained clinically significant scores on the following scales: Bulimia (32.8%),

Interpersonal Insecurity (43.1%), Interpersonal Alienation (43.1%), Emotional

Dysregulation (29.3%), Perfectionism (56.9%), and Maturity Fears (68.1%). These high percentages should not be interpreted as indicators of increased disordered eating within athletics. Although these traits are commonly found in individuals with eating disorders, they are also rather prevalent in nonclinical samples (Garner, 2004). For this reason, the current study was not as concerned with differences between groups on individual

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 22 measures of interpersonal insecurity, maturity fears, emotional dysregulation, or interpersonal alienation; instead, statistical analyses focused on group differences in

General Psychological Maladjustment Composite scores.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to examine the possible relationship between hypercompetitiveness and disordered eating among a population of female intercollegiate cross-country runners. Based on the findings of Picard (1999) and Heffner et al. (2003), it was hypothesized that runners at a high level of competition (D-I) would obtain higher scores on measures of disordered eating attitudes and hypercompetitiveness than runners at a lower level of competition (D-III). It was also predicted that D-I athletes who received scholarships for athletic participation would display an increased tendency to possess these maladaptive traits. Although data analyses revealed that neither level of competition nor scholarship status accounted for any significant differences in HCA or

EDI-3 scores, hypercompetitiveness was found to be significantly correlated to several different measures of disordered eating. This marks the first time that this maladaptive form of competitiveness has been implicated as a possible indicator of eating disorder risk within the realm of athletics.

The current findings provide support to Burckle et al.'s (1999) research study in which hypercompetitiveness was found to be significantly correlated to disordered eating within a nonclinical sample of university women ( r = .40, p < .001). The presence of a similar significant relationship ( r = .52, p < .001) within the current sample of female cross-country runners lends further support to Karen Horney's assertion that hypercompetitiveness is associated with maladaptive personality traits and unhealthy

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 23 behaviors across a myriad of settings (as cited in Ryckman, Thornton, & Butler, 1994, p.84). Within the realm of athletics, hypercompetitiveness may be perceived by others as an intense “will to win” in which the athlete is willing to make extraordinary sacrifices in order to succeed. In a sport that emphasizes leanness for optimal performance, this “winat-all-costs” attitude appears to be expressed through an acute drive for thinness and a relentless pursuit of perfection. Although restrictive dieting and excessive physical exercise are often cited as behavioral manifestations of underlying eating disorder psychopathology, coaches and teammates may misperceive these behaviors as indicators of a “good athlete” who is admirably committed to her sport (Thompson and Sherman

(1999b).

The current study empirically supports Thompson and Sherman's (1999b) proposal that an overly intense drive to win and maintain performance thinness may be indicative of low self-esteem, general psychological maladjustment, and an underlying dissatisfaction with self. Based on the current research, hypercompetitive athletes tend to be perfectionists who are extremely self-disciplined and find it difficult to be pleased with athletic performance. Thus, according to Ryska (2002b), these runners may be more likely to become frustrated with performances that do not live up to their high standards of excellence. These frustrations are associated with decreased task persistence pending failure, and may even lead to burn-out. Furthermore, the observed relationship between hypercompetitiveness and perceived pressure from coaches could be indicative of a Type

E orientation in which the athletes feel as if they must be successful in order to gain social acceptance (Ryckman, Thornton, & Butler, 1994). Their own intensely felt pressure to excel may lead them to more acutely internalize their coaches' expectations.

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 24

Because people with a Type E orientation typically have a strong need to please everyone around them, they may feel as if anything short of perfection will be perceived as a disappointment (Ryckman, Thornton, & Butler, 1994). Along this line of thinking, a heightened drive for thinness may be one way for the hypercompetitive athlete to seek acceptance from coaches, peers, and self.

Additional support for hypercompetitiveness' relationship to disordered eating comes from the finding that pressure to maintain scholarship and pressure from coach to excel were not significantly related to the overall EDI-3 score. This suggests that external pressures alone do not pose a significant risk; it is the presence of a hypercompetitive attitude that appears to be associated with a tendency toward disordered eating.

However, although there was no significant correlation between the pressure to maintain athletic scholarship and general eating disorder risk, the current study did find that scholarship pressure was associated with perfectionism, drive for thinness, hypercompetitiveness, and perceived coaches' pressure. This is the first time that these variables have ever been empirically implicated as correlates of scholarship pressure.

These findings suggest that scholarship runners who are more perfectionist in orientation place considerable pressure on themselves to excel and may feel that losing weight and maintaining a thinner physique will give them a competitive edge. This attitude is especially dangerous among hypercompetitive athletes who rely heavily on achievement and social comparison for feelings of self-worth (Ryckman, Thornton, & Butler, 1994).

The strong association between hypercompetitiveness and disordered eating suggests that, irrespective of competition level or scholarship status, athletes whose feelings of

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 25 self-worth rely too heavily on competitive outcomes should be closely monitored by coaches for unhealthy eating attitudes and behaviors.

The current study's inability to support previous research concerning the effect of level of competition on rates of disordered eating may have been due to methodological flaws and limitations. Due to the limitations of undergraduate research, intentional random sampling was not a plausible method. Instead, this study relied on personal contacts and coaches who expressed a genuine interest in the research topic. Thus, there is the possibility that self-selection may have created a sort of response bias in which teams who participated had the intent of creating a more positive image for their sport.

Also, other response biases may have arisen because the athletes of participating programs received no compensation for their participation and were not required to participate. In particular, athletes with eating disorders may have chosen not to participate because they were nervous about having their disorder documented on paper.

Furthermore, because of the participating programs' broad geographic range, it was not feasible for the primary researcher to administer the tests in person. Because it was suggested in previous studies that athletes may under-report symptoms of disordered eating in the presence of their coaches (Garner, 2004), the researcher relied on team captains and athletic trainers to distribute and collect the questionnaires. Even though the athletes were assured that their participation in the study would not impact their team standing and that their individual results would not be released to their coaches, some athletes may have been wary of handing confidential information to their athletic trainer or team captain. Although the primary researcher provided the test administrators with guidelines for administration and the maintenance of confidentiality, the researcher had

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 26 no way of knowing whether or not the guidelines were carried out in a uniform fashion.

Possible discrepancies in administration could have resulted in biased answering.

The reliance on voluntary participation also resulted in an unequal sampling of scholarship ( n = 42) and non-scholarship ( n = 74) athletes. Because scholarship pressure was found to be correlated with certain maladaptive traits, it seems imperative that future research be conducted with larger samples of scholarship athletes. The NCAA seems to be one of the few organizations that would be capable of a larger-scale study of the possible effects of pressure to maintain athletic scholarship on disordered eating and other unhealthy attitudes and behaviors. In addition, researchers could ask more direct questions concerning sport-specific pressure to maintain performance thinness versus social pressure to maintain appearance thinness (Johnson, Powers, & Dick, 1999).

As is the case in many psychological studies, self-report measures always run the risk of under-reporting symptoms. Although this study was not interested in the diagnosis of eating disorders, the EDI-3 is best interpreted when combined with behavioral observations and physiological measures. For example, drive for thinness and body dissatisfaction are more closely related to eating disorder risk when the individual is at an average or below-average weight (Garner, 2004). Because this study did not ask for participants to report their weight and height for body mass index (BMI) calculations, there is no way of knowing if certain athletes were preoccupied with losing weight because of a legitimate need to reduce certain health risks. Also, analyses of the BMI data would have provided insight into how many of the participating athletes were at risk for amenorrhea, a dangerous eating disorder symptom that is a key component of the “female

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 27 athlete triad”. Future studies could try to see if hypercompetitiveness and pressure to maintain scholarship are correlated with BMI.

The current study proposes that within the context of sport, hypercompetitiveness should be viewed as a personality correlate of disordered eating. This being said, coaches may be able to help promote the physical and emotional health of their athletes by communicating to each team member that self-worth and social acceptance are not contingent on athletic performance or physical appearance. It may also be beneficial to talk to runners about competition in terms of personal development and growth (Burckle et al., 1999). Coaches should be alerted by athletes whose perfectionist tendencies appear to lead to excessive disappointment and self-doubt. Because hypercompetitiveness is so strongly associated with a need for pleasing others, it may be helpful for coaches to tell their athletes that they do not expect perfection. In addition, coaches should continue the current trend of phasing out team weigh-ins because the hypercompetitive individual could potentially use these weigh-ins as another venue for unhealthy competition. The findings of the current study suggest that future research should focus on finding effective ways to prevent disordered eating and discourage hypercompetitive attitudes within female populations.

References

Academy for Eating Disorders (2007). Prevalence of eating disorders.

Retrieved April 16,

2007, from http://www.aedweb.org/index.cfm

Berry, T.R., & Howe, B.L. (2000). Risk factors for disordered eating in female university athletes [Electronic version]. Journal of Sport Behavior, 23(3), 207-218.

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 28

Burckle, M.A., Ryckman, R.M., Gold, J.A., Thornton, B., & Audesse, R.J. (1999). Forms of competitive attitude and achievement orientation in relation to disordered eating. Sex Roles, 40, 853-870.

Carlton, I. (2007). Athletes and eating disorders- Too thin to win: why athletes who lose weight to enhance performance are dangerously misguided. Peak Performance.

Retrieved February 27, 2007, from http://www.pponline.co.uk/encyc/athleteseating-disorders.html.

Crandall, C.S. (1988). Social contagion of binge eating [Electronic version]. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 55(4), 588-598.

Davis, C., & Strachan, S. (2001). Elite female athletes with eating disorders: A study of psychopathological characteristics. Journal of sport and exercise physiology, 23,

245-253.

Faer, L.M., Hendriks, A., Abed, R.T., & Figuerdo, A.J. (2005). The evolutionary psychology of eating disorders: Female competition for mates or for status?

[Electronic version].

Practice, 78,

Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, and

397-417.

Garner, D.M. (2004). The Eating Disorder Inventory-3 Professional Manual. Lutz, FL:

Psychological Assessment Resources.

Garner, D.M., & Olmstead, M.P. (1984). The Eating Disorder Inventory Manual. Odessa,

FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Gotwals, J.K., Dunn, J.G.H., & Wayment, H.A. (2003). An examination of perfectionism and self-esteem in intercollegiate athletes. Journal of Sport Behavior, 26(1), 17-

38.

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 29

Heffner, J.L., Ogles, B.M., Gold, E., Marsden, K., & Johnson, M. (2003). Nutrition and eating in female college athletes: A survey of coaches [Electronic version].

Eating Disorders, 11, 209-220.

Johnson, C., Powers, P.S., & Dick, R. (1999). Athletes and eating disorders: The National

Collegiate Athletic Association study [Electronic version]. of Eating Disorders, 26, 179-188.

International Journal

Mintz, L.B., & Betz, N.E. (1988). Prevalence and correlates of eating disordered behaviors among undergraduate women. Journal of Counseling Psychology,

35(4), 463-471.

Picard, C.L. (1999). The level of competition as a factor for the development of eating disorders in female collegiate athletes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 28(5),

583-594.

Ryckman, R.M., Thornton, B., & Butler, J.C. (1994). Personality correlates of the hypercompetitive attitude scale: Validity tests of Horney's theory of neurosis

[Electronic version]. Journal of Personality Assessment, 62(1), 84-94.

Ryska, T.A. (2002a). Perceived purposes of sport among recreational participants: The role of competitive dispositions. Journal of Sport Behavior, 25 (1), 91-108.

Ryska, T.A. (2002b). Self-esteem among intercollegiate athletes: The role of achievement goals and competitive orientation. Imagination, Cognition, and Personality,

21 (1), 67-80.

Scott, P. (2006, September 14). When being varsity-fit masks an eating disorder.

New

York Times.

Retrieved February 28, 2007, from http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/14/fashion/14Fitness.html?_r=1&oref=slogin.

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 30

Steiner, H., Pyle, R.P., Brassington, G.S., Matheson, G., & King, M. (2003). The college health related information survey (C.H.R.I.S.-73): A screen for college student athletes [Electronic version].

97-109.

Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 34(2),

Stout, E. (2007, February 16). What the stopwatch doesn't tell. The Chronicle of Higher

Education: Athletics, 53(24). Retrieved February 13, 2007, from http://chronicle.com/weekly/v53/i24/24a04401.htm

Striegel-Moore, Silberstein, L.R., Grunberg, N.E., & Rodin, J. (1990). Competing on all fronts: Achievement orientation and disordered eating. Sex Roles, 23, 697-702.

Taub, D.E. & Blinde, E.M. (1992). Eating disorders among adolescent female athletes:

Influence of athletic participation and sport team membership [Electronic version]. Adolescence, 27(108), 833-848.

Thompson, R.A., & Sherman, R.T. (1999a). Athletes, athletic performance, and eating disorders: Healthier alternatives. Journal of Social Issues, 55(2), 317-377.

Thompson, R.A., & Sherman, R.T. (1999b). “Good athlete” traits and characteristics of anorexia nervosa: are they similar? [Electronic version]. Eating Disorders: The

Journal of Treatment and Prevention, 7, 181-190.

Torstveit, M.K., & Sundgot-Borgen, J. (2005). Participation in leanness sports but not training volume is associated with menstrual dysfunction: A national survey of

1276 elite athletes and controls [Electronic version].

Medicine, 39, 141-147.

British Journal of Sports

Weight, L.M., & Noakes, T.D. (1987). Is running an analog of anorexia? Medicine and

Science in Sports and Exercise, 19(3), 213-217.

Hypercompetitiveness and Disordered Eating 31